How might it be possible to enact tenets of treaty—like mutual accountability, reciprocity, relation across difference and stewardship of resources—in the art world? What does it mean for a settler-colonial art institution to unknow its power? Why should artists and art organizations, whether Indigenous and settler, be cautious of using words like “Indigenize” and “decolonialize” to describe their work?

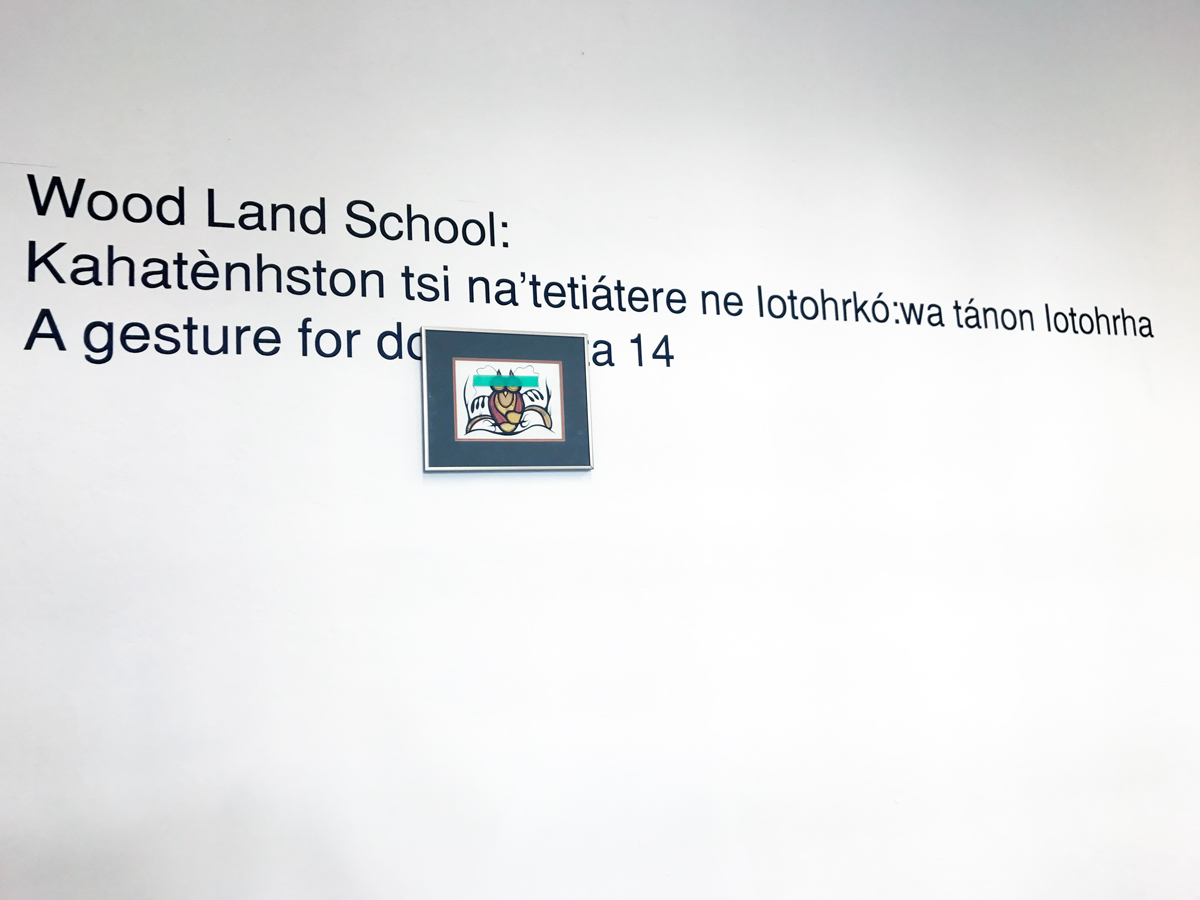

These are just some of the questions being explored right now in “Wood Land School: Kahatenhstánion tsi na’tetiatere ne Iotohrkó:wa tánon Iotohrha / Drawing Lines from January to December,” Wood Land School’s in-depth, year-long project in Montreal. In many ways, the project is a case study in working through a temporary Indigenous reimagining of an institution—and it’s unfolding publicly, in real time.

Earlier this year, curator John Hampton spoke in depth with members of Wood Land School about the inception of “Drawing a Line.” (That discussion is archived here.)

Now, in this post, Hampton and the collective members address Wood Land School’s recent travels to participate in Documenta 14’s Under the Mango Tree—Sites of Learning, which explored informal and artist-led educational initiatives. This interview was recorded on July 24, three days after the group returned from Kassel and Athens.—Leah Sandals, managing editor, online

John Hampton: Welcome back to Canada.

Tanya Lukin Linklater: We were calling it Turtle Island while we were away, or North America.

cheyanne turions: I was referring to it as “the land now known as Canada.”

As part of Under the Mango Tree we led a workshop, where we talked about treaty, residential schools and the different kinds of histories we are thinking through in this project. We had a generous audience, but it wasn’t clear to me whether the nuance of what I was saying translated. I’ve been thinking about how people understand what has happened in North America as part of European history. I was curious to feel out how the colonial spectre extends back to that continent, and what a general understanding of that project is to Europeans, now.

TLL: One of the terms that was unclear for people was “settler colonialism.” There were challenges around language, and the translation of our experiences as Indigenous people in Canada. There were some shared experiences across difference but a specificity of participants’ experiences within states, histories, and to the lands that people live within.

ct: While we were there, we really tried to consider what it meant for us to be people that were from elsewhere. Before we departed, the documenta organizing group asked the participants to bring a seed with them to plant in Athens, and Duane, Tanya and I felt uncomfortable with that: a) I think it’s illegal to transport seeds across international borders? and b) What does that mean to come from somewhere else and bring in something that could be an invasive species in that climate (for all we know), plant it there, and leave it for other people to tend, or for it to become bird food?

They asked us in this very poetic way to come plant a seed, and we were just felt unsure about it.

JH: That sounds like a beautiful gesture that also happens to encapsulate the codependent relationship between colonial/hegemonic agendas and international academic and art gatherings. All these different nations going to one spot and planting seeds of knowledge, culture, or ideas in a foreign territory, seeds that are going to sprout and live forever.

TLL: Some participants strategized well around this request. Sofía Olascoaga went to the market to gather her seeds, and talked about how certain markets have been sites of trade for hundreds or even thousands of years. Someone else took the seeds from the orange they had eaten in the morning. They found ways to make well-considered gestures that were allowable within the parameters of the request.

I think about seeds of plants indigenous to North America, and it didn’t make sense for me to bring those. A concern of ours was: Who will continue to care for and tend to the seeds so that they grow? We were very well cared for by the group of people that brought us there, and I felt in relation to/with the people who came together at this place at this time, to share ideas. We felt kindnesses and generosities. Being in relation to these folks, having travelled so far, felt significant. But the question remained: Who would tend to the seed in that garden?

JH: Can you describe some of the things that you did bring with you?

TLL: As Wood Land School, we decided to hand-carry works from where we live to Kassel, and we installed them in a modest, provisional space in the Stellwerk. We called this A gesture for documenta. Each of us brought works by artists—some from previous iterations of Wood Land School in Montreal; I brought Layli Long Soldier‘s Whereas, a book of poetry, and read two of her poems in the workshop, as well as a collaborative video by Elisa Harkins and Nathan Young. We also installed work by a few artists that will be in the fourth gesture in Montreal, opening September 21.

ct: I brought a drawing of a skidoo blanket cover by Jeneen Frei Njootli because it’s beautiful, but also because it was given to me. I think that relationality—the space between people—is important to this Wood Land School project that we’re doing in Montreal right now. I wanted to bring this drawing because I bore an intimate relationship to it.

I also brought a perpetual calendar by Maggie Groat, which is a sort of algorithm to figure out the days of the week and the month into the future forever. This Wood Land School project is a lot about time—the past, the present, the future, what we do with it. This perpetual calendar is a way of reconstructing a line of history into a circle. And then I brought an ovoid work by Charlene Vickers.

The Plains Indian Sign Language from Elisa Harkins on Vimeo.

Duane Linklater: This thing that we did at Documenta was an extension of what we began in Montreal—that thinking, collaborating, and working, its problematics and processes. We very much see our time in Germany and Greece as an extension of our time in Montreal. We made a decision to select works because we had limitations in what we could do. For myself, those limitations were productive, but we had to make quick decisions about who was included in the exhibition.

It will take a little bit of time to unpack, but I have had some thoughts that have lingered throughout our time there. In Athens in particular: the city has made some decisions in recent history to preserve a certain kind of narrative about itself.

An interesting thing happened when Tanya and I went to a restaurant in a tourist district. I went to the bathroom downstairs, and there is a glass floor that you can see ruins through. This restaurant is built on ruins, but it didn’t want to fully destroy them, it wanted them to be visible. And there are other examples of new architecture making itself malleable to show the history underneath it. It is an interesting contrast to here in North America, where buildings are built and there is no effort to preserve what is underneath.

ct: This founding doctrine—as far as Canada is concerned—of terra nullius plays itself out in material form. When [Duane] described this experience of the folks in Greece trying to literally preserve remnants of what came before…it made it very clear to me.

DL: This is a state decision to preserve itself, but it’s only preserving one kind of narrative about itself, which is interesting and also problematic—but there is still this state effort to do that. In Canada, the United States, and even in Mexico, there’s very little effort to make those preservations, to protect those identities, to protect those sites.

Often those sites in Canada, including gravesites, are paved over or erased. Oka is one of the most infamous examples of that, where they wanted to build a golf course over significant Indigenous spiritual places. The gesture for preservation, in that case, was made by the people of Kahnawake and Kanesatake to repel settler colonial land management. They wanted to change the land without any consequence.

Back to this experience, I still need to think it through, but it was interesting in contrast to the lands we find ourselves in, where there is no consequence for building. Even when they find things of our ancient history, there is no protection. For example, the recent destruction of petroglyphs in Ontario.

JH: Here in Manitoba, a series of petroforms that I just visited at Bannock Point were rearranged to make an inukshuk.

DL: That’s crazy. There’s no protection for these sites at all. There’s no consequences for the people who graffiti over or desecrate our sites. There needs to be a protection for our sites of Indigenous art history, they are ancient sites and there needs to be consequences for the people who destroy them. This experience in Athens brought a lot of this thinking to the forefront.

A view of Wood Land School’s project at Documenta 14. The print is an unverified Joshim Kakagamic from the collection of Duane Linklater found in North Bay.

A view of Wood Land School’s project at Documenta 14. The print is an unverified Joshim Kakagamic from the collection of Duane Linklater found in North Bay.

JH: It’s interesting that you say that their preservation of architecture and history is in contrast to the way that Canada functions. I think they are actually part of the same ideology. Both systems and governments understand the cultural and political power of history—of the deep physical history of land, architecture, space and people.

In Greece, the preservation of their history bolsters the legitimacy of their own country, but in Canada the opposite is true. Canada 150 bolsters as much history as it can. It tries to make 150 sound like a big number, to try to suggest there is a long history that supports what Canada is as a nation. Historical sites with thousands or tens of thousands of years of history have a lot of power behind them. To recognize those immense histories, though, would undermine the weight of Canada’s history or legitimacy as a governing nation.

DL: I like how you say “making it sound like a big number.” It’s important to say that Canada, as an idea, as a state, as a place, is really in its infancy. We have particular relationships to our lands and histories that are ancient. Considering the tens of thousands of years that we have spent in our respective homelands, a celebration of 150 years is laughable.

JH: That’s an important perspective, but I’m also curious how that dialogue changes when you travel outside your respective homelands to Montreal, New York, Athens and Kassel. I’m interested in how that role changes, and responsibilities shift, when you realize that you are in a country across the ocean and probably shouldn’t bring seeds to carelessly plant in that area.

TLL: If we had just gone to Germany and were expected to present there—not knowing who our audience was—it would have been a very different workshop. But the closed sessions in Athens allowed us to be with other folks from across the world who are working in the field of radical arts education or learning—I saw this group as my primary audience.

I think this shifted the way I told the story that I needed to tell about Wood Land School. I was speaking to people who may not fully understand what it is that we’re doing, but certainly have a point of reference from their own practices.

A score generated by Tanya Lukin Linklater with participants.

A score generated by Tanya Lukin Linklater with participants.

ct: In the space of the workshop proper, when our conversation as Wood Land School was open to the group of people who gathered with us, there were two instances where it became obvious that at least some of the work we need to do in an international context is the same work we need to do at home.

One was when Duane spoke about residential schooling. There we were at an international gathering about education and alternative schools, and Duane shared that history as a broader contextualization of the violence of Western modes of education. If we are going to re-imagine what education is, we need to have an understanding about what education has been.

This is a history of education that people are too willing to exclude in the critical narrative of where we have been and where we want to go. Duane took the time and care to have those facts be present in the space of the workshop, which is akin to the project we are doing here, which is to insist that this history is part of the Canada 150 narrative, for instance.

There is another instance with this young fellow in the workshop who was really frustrated with us sitting around and talking. He said, “We’re supposed to be making an exhibition! I’m going to take this charcoal, and just draw on the floor because I’m just so violent and radical!”

And Tanya just absolutely refused the interpretation of his gesture being radical. She situated that kind of a gesture in a larger history of how violence has structured the lives of Indigenous people in North America, and just fucking refused to have him take up that kind of space. There are many ways that the larger project of Wood Land School shifts and changes when it goes into an international context, but in those two specific instances, I really saw that it is the same project.

DL: That’s interesting that you pair those two events, cheyanne. I felt that it was important to talk about residential schools. This is a gathering about education, and we were invited to make a contribution to this situation. For myself, it was important to talk about the context in which different forms of education rub up against each other and create friction. There were many articulations of the forms and systems of education, and I wanted to tell people that in my family’s experience, our interaction with colonial and religious forms of education were violent.

And this continues to have a resonance in North America, with the boarding schools in the United States, and the residential schools here in Canada. Those resonances are still being worked through. I guess I wanted to show that I am working through that, in my own way, and my own history, since my family went to these schools. I wanted to show that I’m working through the legacy of what my family went through at those schools.

I’ll add a third thing to what cheyanne was saying: In the first days that we were in Athens, one of the artists/education groups, who were showing work in the Athens part of documenta, gave us an artist talk in front of their work. Within this talk, there was a group of words that made me feel very upset—the words that I remember are that “the Americas were a gift.”

ct: He was talking about Columbus coming to America and the gist of it was that Columbus didn’t find the land, because he wasn’t searching for it, and therefore the land was a gift.

DL: Exactly. And right away I almost said something, but I let him finish, and waited till the question-and-answer period. I told him, “I refuse what you’re saying. I refuse to accept your proposition that the Americas were a gift. Our histories, where we come from, say otherwise. We did not gift or give anything to anybody.”

I think this created a position for us during the rest of the gathering. Part of that position, which has been articulated by Tanya and cheyanne, is that there were refusals made by us as a group. I am still thinking through this, but this position of refusal for us was important and productive.

TLL: Candice Hopkins joined our workshop [at Documenta] and seemed compelled by time and the way in which the exhibition in Montreal unfolds slowly. She noticed in Kassel that this person’s—what he called “violent” or “aggressive”—gesture was perhaps connected to a feeling of urgency, that there is an aggression that happens because of the constraints of time.

I refused his interruption, saying that a more radical gesture holds the work of these artists in kindness and compassion because we, as Indigenous peoples, live within a colonial situation that is continuously and relentlessly violent, everyday. I was very direct. I spoke like an old aunty in that moment. He may have been tired of us talking. Conversation is a methodology in Wood Land School, and a form of knowledge production; as Indigenous people we often (but not always) generate knowledge within orality.

In this workshop, and even in this conversation with you, John, I’m very conscientious about when we take space, and how difficult it can be to take space, and how difficult it can be to listen. I talked about my own lack of comfort, but also spoke about my experience listening deeply, and in a sustained way for many years. I am now at a time in my life where I feel that it is part of my responsibility to speak, and to speak in relation to the situation that Indigenous people face in Canada and the United States.

JH: Radicalism is often thought of as being fast, and violent, pushing an ideology onto others. In that approach, there is a subtly implied lack of consent. In this sense of the term, it is very much in line with very protectionist and classic colonial forms of education. I like your reframing of radicalism to associate it with slowness, refusal, care and kindness. In the context we are discussing and living with, those concepts are truly radical.

A detail view of a collaborative score work by Tanya Lukin Linklater and participants at Wood Land School’s project for Documenta 14.

A detail view of a collaborative score work by Tanya Lukin Linklater and participants at Wood Land School’s project for Documenta 14.

TLL: Refusal is significant because of the commitment to speak when it is difficult and uncomfortable. Certainly Duane modelled that behaviour early on, in the way he asserted his initial refusal. I’m also aware of the power relations in the workshop, as “participant” vs. “leader.”

I might approach this kind of situation differently in the future. Duane and cheyanne understood my position, but were also gentle in their subsequent conversations regarding why I needed to say what I said. This is a strength of working collaboratively and collectively—we supported one another, we had a lot of conversations throughout, and we picked up ideas, threads or responses that might otherwise have fallen to the side.

DL: There could have been more refusals than we made that week, but making refusals is exhausting labour. It happens so often here in North America, but also happens in Europe, daily. You go around the world, and you still run up against this settler colonial mentality, and articulations of that thinking in contemporary art.

From my perspective, it’s a global condition. The normativity of that thinking was bothering me, and even more so was that these articulations were accepted by audiences without much critical response. We were able to deliver some critical responses, but I felt somewhat limited because I can only make so many refusals. It could be an unending task.

JH: It seems like part of the premise of Under the Mango Tree would be about bringing international allies together to exchange models for education that were outside of colonial, neo-liberal and dominant ideologies. Then these various small groups from across the world would all share their experiences and hopefully learn from each other and from the strategies they take in their own specific circumstances.

It sounds like some of that did happen, but sometimes it happened through tensions and refusals, with disagreement being an essential part of that exchange rather than just whole-hearted adoption—saying, “That would work in my local franchise.”

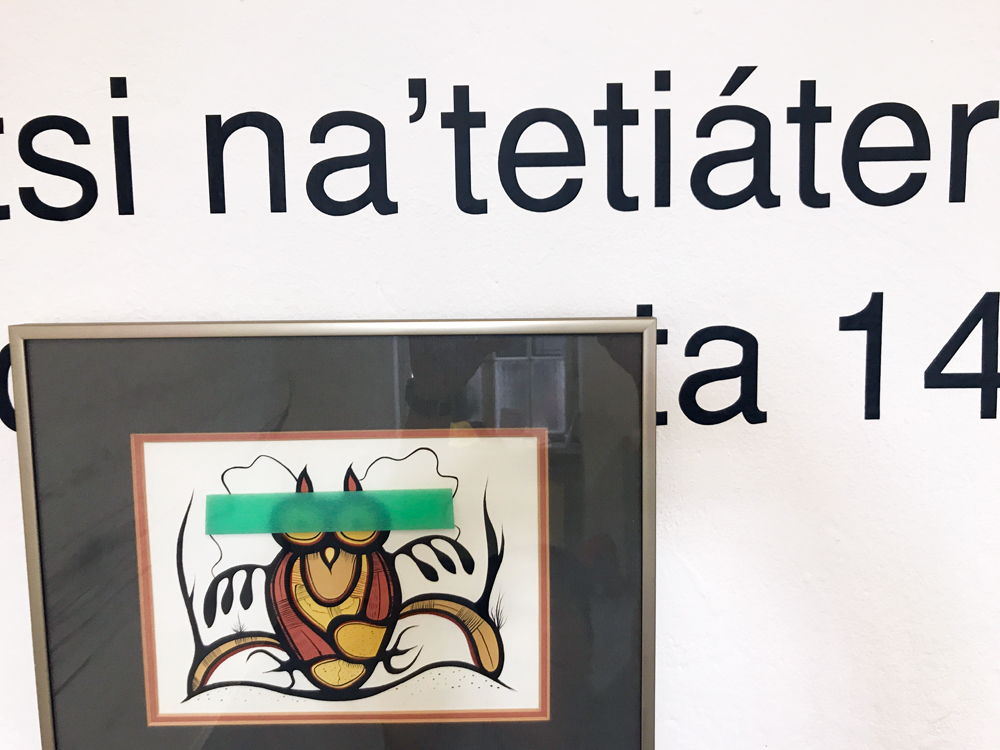

A print thought to be by Joshim Kakegamic, altered with green masking tape by Duane Linklater and hung over wall vinyl at Wood Land School’s project for Documenta 14.

A print thought to be by Joshim Kakegamic, altered with green masking tape by Duane Linklater and hung over wall vinyl at Wood Land School’s project for Documenta 14.

TLL: There were seeds of ideas that were planted with me that will take a long time to process, engage with and consider their implications for my arts practice and as a member of Wood Land School. Many people spoke about how these points of tension were difficult, but they were also generative, because they allowed for further engagement, conversation and the ideas to be pulled apart. If everyone was polite, we never would have gotten to these harder conversations.

For the third work I brought to the workshop/exhibition, I think we found our way towards a collaborative production, using the body, intuition and negotiation. I asked that we discuss and decide where we would make a line on the wall. We crushed willow charcoal in our hands, and then placed one or both hands on the wall.

A participant asked about how the gesture should begin. This was a moment where he was listening, and he felt that it was important that I begin the gesture. The group then took the gesture in unexpected ways, and it became this lovely score on the wall that I had never fully anticipated. We felt joy for the ways people took this up.

I think they needed to have this moment, to mark-make, and to be a part of something larger than themselves. That was hopefully significant for the participants, and certainly was for myself as someone who instigated it but then watched it unfold.

JH: That’s a really beautiful image. I also really liked the Joshim Kakagamic print over the word “documenta” in the exhibition didactics, which was an interesting way of articulating the refusals we were discussing, addressing the politics of naming and claiming.

DL: I found that print here in North Bay, at Value Village. I was very excited to see it on the shelf at the store, and I bought it for $10. I opened the frame to hopefully see a Joshim Kakagamic signature; I did not, but I did see hand numbering of the edition.

We brought this work into the exhibition as an “unverified” Joshim Kakagamic work, but I am fairly certain that it is. I did a bit of research and discovered that he did a printmaking residency here around 1984. I think that this print is a result of that time spent here in North Bay. It’s been on my wall since I found it here, and I placed a piece of green painter’s tape over the Owl. There was a refusal from me about that particular bird for a number of cultural reasons, but I still maintain the value of this particular artist and am very happy to have it here in my home.

I told this story to the people that were there at that time, and I decided to place this particular artwork in a section of the exhibition that could speak to multiple resonances of refusal. I didn’t realize it until our new friend, Rangoato Hlasane, mentioned it. He said, “I like what you did here, how you refused one thing, and then another, and made a layering of refusals.” It was a very intuitive and spontaneous gesture to do that.

John G. Hampton is a curator and artist currently living in Treaty 2 territory, Manitoba. He is the executive director of the Art Gallery of Southwestern Manitoba, adjunct curator at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, and sits on the board of directors for the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective. He was born in Boston of Chickasaw and European ancestry in 1985.

Works by Jeneen Frei Njootli (left) and Charlene Vickers (centre) at Wood Land School’s project for Documenta 14’s Under the Mango Tree.

Works by Jeneen Frei Njootli (left) and Charlene Vickers (centre) at Wood Land School’s project for Documenta 14’s Under the Mango Tree.