There’s a piece of white marble installed on the second floor of the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto that might not attract attention at first glance—but it deserves to.

This piece of marble is a couple of feet tall, tops. It’s very old: one side was carved in the Roman era, the third century, with curving, acanthus-leaf designs, while another side was carved in the 10th century, with Kufic script telling the tale of a leather merchant.

This marble, a wall text tells us, came from Egypt, or maybe North Africa more generally. Once it was, perhaps, part of a railing or building (as the decorative pattern suggests). Then it was repurposed (as the Kufic script suggests) to become part of a funerary stele, part of a tombstone.

And now, this piece of marble—this railing, this funerary marker, this museum artifact—is the physical and metaphorical touchstone at the centre of “Here,” an exhibition of contemporary Canadian art marking Canada 150 at the Aga Khan Museum.

“I love that idea of one object becoming something else,” curator Swapnaa Tamhane says in a pre-opening tour of the show, “also that there are two time periods which are so far apart inscribed on one object.”

“The stele…could be seen to represent the contemporary Canadian—who may be from several geographies, and is inscribed with each of these locations,” Tamhane elucidates in a wall text.

And so the works in the exhibition, like the artists in it, and the artifact that inspired it, cross time and space in complex—and also, given the nature of contemporary Canadian life, very commonplace—ways.

“The Aga Khan talks a lot about pluralism, and I thought that’s an interesting way to also approach being Canadian right now,” Tamhane says. Her own personal history began in Toronto, shifted to Saudia Arabia’s expat community for several years and then returned to the city. For the last 15 years, she has moved between Canada, India, the UK and Germany.

Her challenge now, to herself and others? “To move beyond” the usual discussions of Canadian identity and “look at something that is more complex, to understand the complexity of culture.”

Jaret Vadera, Detail of film still from Ascent, 2009/2017. Two-channel video installation. Copyright © Jaret Vadera Courtesy of the artist.

Jaret Vadera, Detail of film still from Ascent, 2009/2017. Two-channel video installation. Copyright © Jaret Vadera Courtesy of the artist.

From Flemingdon Park to (and from) the World

From the site of the Aga Khan Museum—a striking, square white-stone building with a large reflecting-pool plaza opened in 2014 as a centre dedicated to the heritage of Muslim civilizations—one can see the nondescript high-rise apartment block in Flemingdon Park where artist Jaret Vadera grew up in the 1970s and 1980s.

“My parents migrated in the ’60s and ’70s from India and from the Philippines,” Vadera says over the phone. “And like a lot of people they ended up in Flemingdon Park on their way to the 905. I went to school a few blocks way from where the Aga Khan is.”

Today, Vadera is an artist, a recent teacher on art, ethics and critical race theory at Yale, and a resident not only of Toronto, but also of New York and Delhi.

And even when Vadera is part of an exhibition that is framed—at least by its marketing materials—as marking Canada 150, he wants to make sure that the exhibition’s discussions of Canadian identity and history embrace the complicated and the contradictory.

“Some people are looking at the show to evidence Canadianness in a short form or something,” Vadera says. “But I think part of the idea was that it was never going to fit into a short form. It was always going to be something that is really layered.”

Vadera’s works in this exhibition are, too, layered and complex.

One of the first works viewers see in this exhibition is a four-part riff by Vadera titled This, That and the Third. It includes a small drawing of a mastodon; a large, flat vinyl wall work mapping Internet-search server hits for the titular phrase; a more furry, animalesque wall piece; and a video about the old “blind men describing an elephant” parable in which each actor only experiences a piece of the larger animal—while thinking their experience is definitive, rather than partial.

“I was told outrightly [growing up in Flemingdon Park] that Canadians were almost always white, and that it was four to five generations of Canadian that made you ‘Canadian,’” Vadera says, recalling the way other people’s perspectives often missed his own experience growing up. “So I was always defined as Filipino and Indian, even though I was born in Toronto.”

Another series of works by Vadera offer embellishments on vintage illustrations of the human eye—bedazzlings, bedicings, bewitchings all. In a symbolic sense, these could suggest the ways in which individual and national perspectives become concretized and calcified.

“My passport says that I’m Canadian, but my body says something completely different [depending on the viewer],” Vadera says. “And I have a Canadian accent; I have an accent from here. So when people look at you, they don’t quite see you properly. They try to push you into a box.”

Jamelie Hassan, Could we ever know each other…?, 2013. Recycled neon, electrical, and colour photography mounted on Masonite. Copyright © Jamelie Hassan. Courtesy of Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario.

Jamelie Hassan, Could we ever know each other…?, 2013. Recycled neon, electrical, and colour photography mounted on Masonite. Copyright © Jamelie Hassan. Courtesy of Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario.

“Could We Ever Know Each Other in the Slightest without the Arts?”

Not far from the ancient marble touchstone in “Here” is another keynote work in the show: Jamelie Hassan’s two-metre wide reproduction of a Canadian twenty-dollar bill, with a glowing neon maple leaf placed over the words, “Could we ever know each other in the slightest without the arts?”

The neon maple-leaf outline is from a diner in Hassan’s home base of London, Ontario, while the quotation it highlights is from Quebec writer Gabrielle Roy. Also on the bill are reproductions of sculptures by Haida artist Bill Reid.

Repositioning and expanding upon Canadian currency in this way, Hassan raises questions around value, identity and what it means to be located, as the exhibition title puts it, “Here.”

“I have done a lot work around pluralism and our relationship to Indigenous issues,” says Hassan, “and that is something I have had discussions on—where do we situate ourselves in this juncture in history? How to raise those issues and be genuinely in dialogue with very crucial and very difficult questions around colonialism—whether it is the impact of that here in Canada, or whether in relation to ongoing situations of conflict in the region of the Arab world?”

Another work of Hassan’s in the show is a stack of cedar disks carved with the silhouette of a cedar. The wood itself is Canadian, and the silhouette is a symbol for Lebanon, home of Hassan’s ancestors.

“My family is a family that came to Canada, well, I go back on my maternal side to 1901, and on my father’s to 1914,” Hassan says. “So we’ve been here longer than some European Canadians. Yet that question of ‘Where are you really from?’ still comes up.”

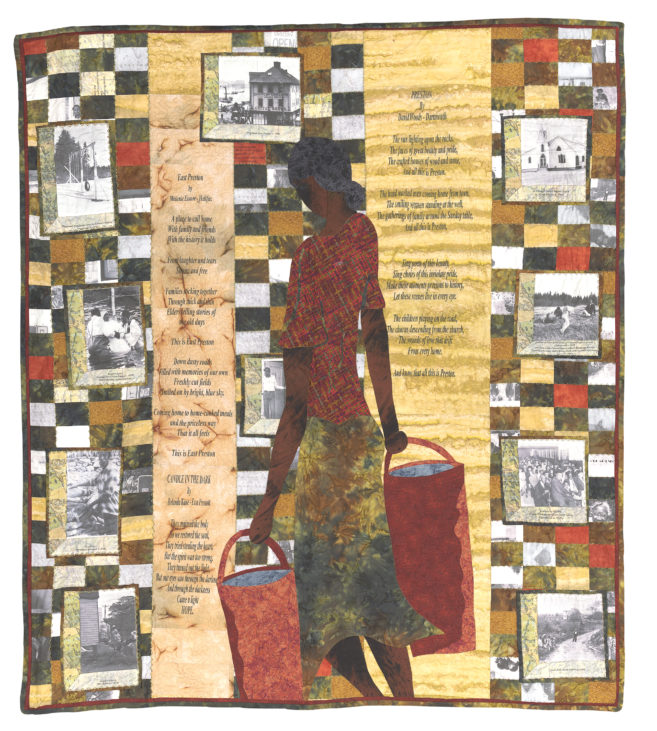

Nep Sidhu, Malcolm’s Smile, 7b, 2015. Wool, poly-cotton, and aluminum. Copyright © Nep Sidhu Commissioned by the Frye Art Museum, funded by the Frye Foundation, Douglas Smith. Made in collaboration with Ishmael Butler.

Nep Sidhu, Malcolm’s Smile, 7b, 2015. Wool, poly-cotton, and aluminum. Copyright © Nep Sidhu Commissioned by the Frye Art Museum, funded by the Frye Foundation, Douglas Smith. Made in collaboration with Ishmael Butler.

Themes and Modes that Interweave, Fold and Refract

Throughout the exhibition “Here,” there are several motifs which come and go.

One, of course, is the journeys through time and space. Vancouver-based artist Babak Golkar is represented with two works from his time capsule series—sculptures which are explicitly understood to actually be vessels for time capsules that are not to be opened for nearly a hundred years hence.

One of these Golkar works is a tombstone-style work made of hydrostone—a material also used in making death masks—that reads “NOTHING IS WORTH DYING/KILLING FOR.” Another time capsule takes the form of a taxidermied fox holding a bare silver tray.

Time and history also come to the fore in Nep Sidhu’s striking three-part textile hanging referencing Malcolm X’s journey to Mecca, as well as X’s criticism of First-Nations oppression. One of the hangings shows a poem about Malcolm X translated into Kufic script—the same script found on the ancient touchstone at the heart of the exhibition. Another panel shows a grid of teepee-like structures, with a large shadow in the background, and another Kufic text encircling.

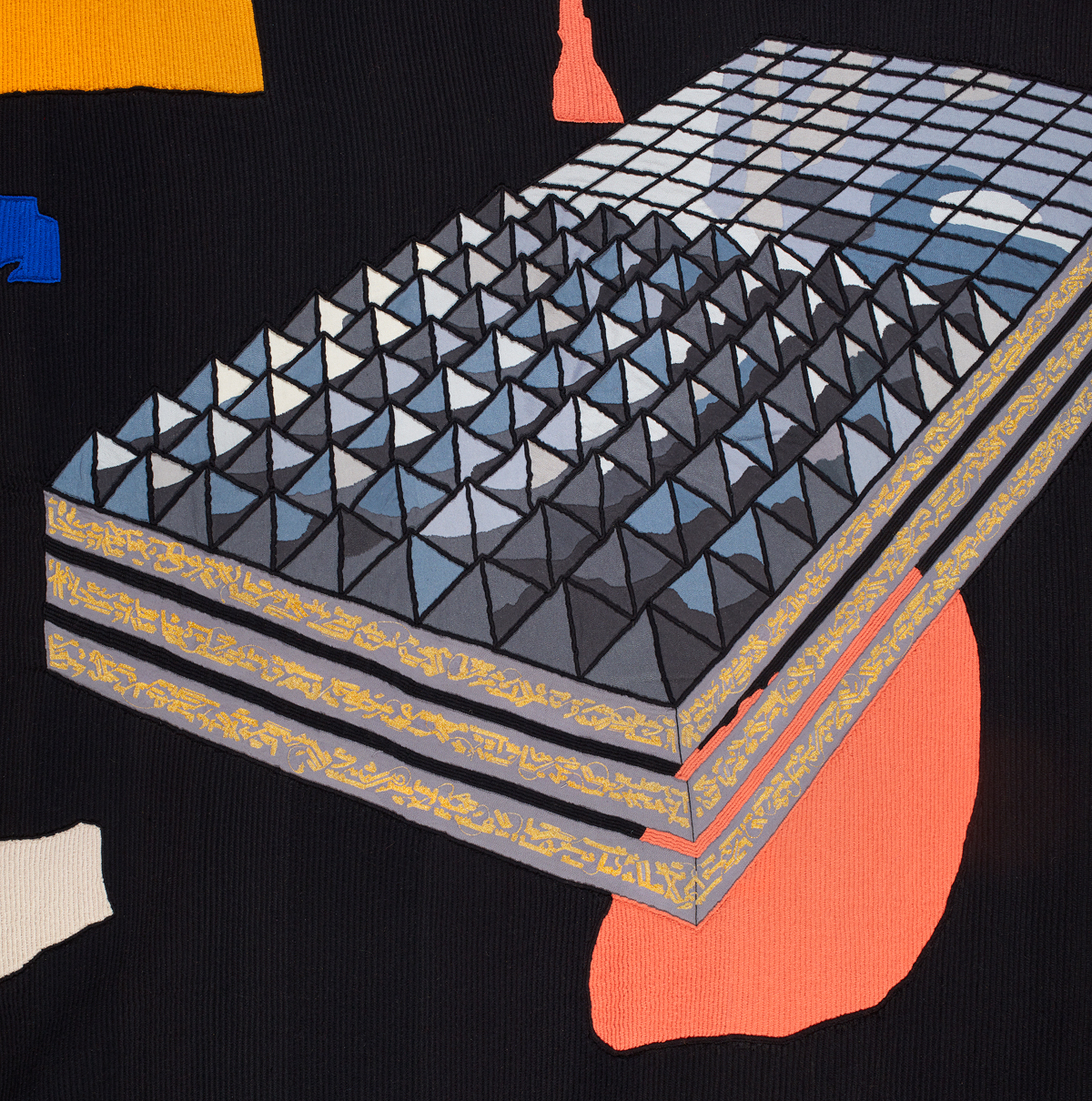

That theme of Indigeneity in Sidhu’s work connects nearby in five bead works from Algonquin artist Nadia Myre. These small pieces rest on a plinth, forming shapes in elemental black and white. Each small beaded piece represents an archetype distilled from Myre’s Scar Project—a project where the artist invited hundreds of people to illustrate and explain their scars, whether physical or psychic.

In their distillation of widespread pain, this brief selection of Myre’s works signals another kind of question about what gets left behind in objects, from ancient touchstones to today’s more minimal or conceptual artworks: What gets concentrated in them? What gets left behind?

Nadia Myre, Circle, 2009. Seed beads and thread. Copyright © Nadia Myre. Courtesy of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, gift of Nadia Myre. Photo: Christine Guest.

Nadia Myre, Circle, 2009. Seed beads and thread. Copyright © Nadia Myre. Courtesy of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, gift of Nadia Myre. Photo: Christine Guest.

From Poetry to Performance Art

The range of media in “Here” also exemplifies a wide embrace of different modes of making in expressing identity and other concerns.

On one wall, in white script on black ground, is an early unpublished poem by George Elliott Clarke. “For me, the poem really describes this Nova Scotia landscape that the Blacks and the Mi’kmaq were pushed off into,” Tamhane says.

On the opposite end of the show is landscape description of a different sort. In the video Hearts and Arrows, Vancouver-based artist Khan Lee is up before dawn, working on an ice carving next to the waterside in Stanley Park. Lee is carving the ice into the shape of a “hearts and arrows” diamond—and when the sun finally refracts through it, the image of landscape changes completely.

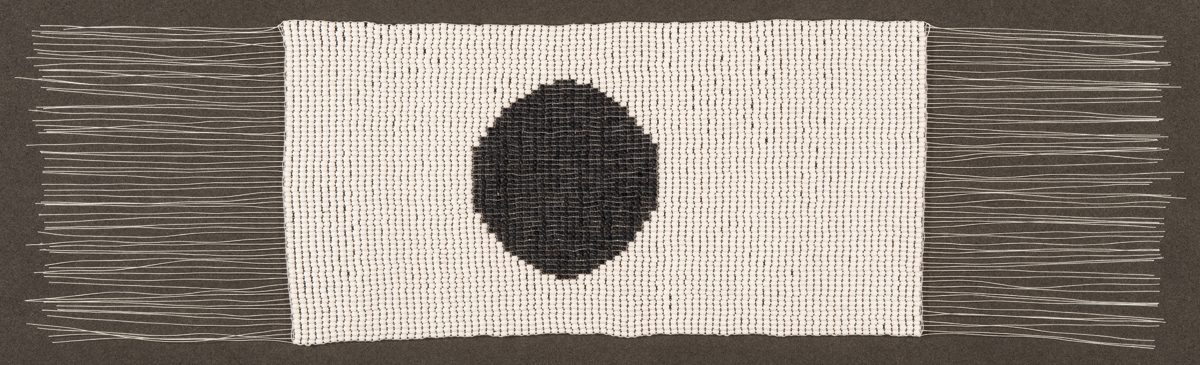

In a nod to the complexity of art and identity—and notions of “here”-ness in general—Brette Gabel has dyed her large Blanket (which hangs in the light-filled museum atrium) with herbs and plants, some of them found in the Don Valley, just adjacent to the Aga Khan Museum. But she has left these dyes unfixed, so that their hues and shades transform and change throughout the exhibition.

Sameer Farooq offers, also in the atrium, ceramic casts of boxes and supports used in the conservation area of the museum. These delicate, breakable ballasts provide a useful bookend to thinking through the limits, as well as the possibilities, of doing an exhibition like “Here.”

“Sameer has this really beautiful line,” Tamhane says. “‘The archive is about not being able to capture the lived experience, and not being able to capture the full story.’ All of his work here is really about what you don’t see.”

Similarly, Tamhane feels concerned that we are not seeing more deeply around Canada 150. “If we are going to talk about ideas around how to unify us, I think that culture is really the only way,” she says.

She wonders about what will come next. “I always think, there are two empty sides,” says Tamhane, reflecting again on the marble piece that links all the works in “Here.” “Let’s see where it lands up in the next thousand years.”

“Here: Locating Contemporary Canadian Artists” opens July 22 at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, with a panel the same day at 2 p.m.

Brette Gabel, Blanket, 2017. Found and recycled cloth, natural dyes. Copyright © Brette Gabel. Courtesy of the artist.

Brette Gabel, Blanket, 2017. Found and recycled cloth, natural dyes. Copyright © Brette Gabel. Courtesy of the artist.

This ancient funerary stele, made of marble, serves as the touchstone for “Here,” an exhibition of contemporary Canadian Art at the Aga Khan Museum. Image copyright Aga Khan Museum.

This ancient funerary stele, made of marble, serves as the touchstone for “Here,” an exhibition of contemporary Canadian Art at the Aga Khan Museum. Image copyright Aga Khan Museum.