Alexia Laferté Coutu

Montreal artist Alexia Laferté Coutu adopted the word “poultice” to describe her sculptures, hinting at the processes used to make them. Laferté Coutu applies soft clay to the surfaces of historical buildings, monuments and plaques, and, like a healing balm, or poultice, applied to skin, the clay absorbs what it is laid upon, creating impressions of textured surfaces that are then cast as counter-forms in glass, plaster and stoneware. “I see the clay as a vector or conduit which allows me to record not only the architectural forms, but also my gestures of pressing the clay against the surface,” Laferté Coutu says. The resulting sculptures, hand-moulded and pocked with fingerprints, introduce a sensory and subjective element to otherwise rigid historical architectures. In “Leurs ombres centenaires,” a 2018 exhibition at Galerie de l’UQAM, Laferté Coutu displayed poultices cast from buildings throughout Montreal on custom tables with steel legs, some with wood-framed tops covered in wool dyed with chamomile and indigo leaves. The vibrant blue and yellow display surfaces emphasized the tactility and translucency of the unpolished glass sculptures, which were arranged throughout the gallery according to their sites of origin. “The multiple associations that the fragments allow are a way to rearrange the historical narratives of the places I investigate,” Laferté Coutu explains. “I seek to disrupt and put into tension the power structures interwoven in colonial architecture and historical monuments.” Laferté Coutu’s sculptures are more than a simple record; they’re preserved moments of material transference. “The sculpture becomes this in-between,” Laferté Coutu says, “speaking to the relationship between materiality and history, one that I believe should be more intuitive, one that we should work to reexamine.”

Sofia Mesa, Process view of Untitled (Spider’s Swing), 2018. Cyanotype on cotton, 3 x 3 m.

Sofia Mesa, Process view of Untitled (Spider’s Swing), 2018. Cyanotype on cotton, 3 x 3 m.

Sofia Mesa

There’s a vein of sensitivity that runs through Sofia Mesa’s work, in both material and approach. In 2016, the Bogotá-born artist, a recent OCAD University graduate, began volunteering every Sunday at Toronto’s Allan Gardens Food and Clothing Share, a grassroots organization that provides food and supplies to low-income communities. After forming friendships with local community members, Mesa began collaborating with them as participants in her projects. In Allan Gardens Proof Blanket 1 (2017), Mesa asked 13 individuals to lie on swaths of fabric treated with light-sensitive materials for an experimental cyanotype, a photographic process that produces vibrant shades of blue when exposed to light. “I wanted to encapsulate a moment there, of our relationships to each other, to the city, to ourselves,” says Mesa. In Guardians (2018), commissioned by the Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival, Mesa’s work expanded into a series of large-scale installations hung throughout the Allan Gardens Conservatory. Allan Gardens Proof Blanket 1 was digitally printed and mounted in the windows of the conservatory in semi-opaque vinyl. Inside were smaller cyanotype banners depicting cedar, sage and tobacco, paying tribute to the First Peoples of the territory upon which the conservatory sits. Larger cyanotype portraits honouring the “guardians” of the project’s namesake—park inhabitants like Thomas and Spider, who play integral roles in maintaining the social ecology of the local area—index the weight and presence of participants, creating a collective record of community.

Jenny Yujia Shi, This Does Not Authorize Re-Entry (detail), 2019. Pen and ink on paper, 20.3 x 28 cm.

Jenny Yujia Shi, This Does Not Authorize Re-Entry (detail), 2019. Pen and ink on paper, 20.3 x 28 cm.

Jenny Yujia Shi

Jenny Yujia Shi became a permanent resident of Canada a decade after relocating from Beijing to start her concurrent BFA and BA degrees at NSCAD University. The interim years encompassed impermanence, adaptation and uncertainty as her immigration status hung in the air. Shi’s artistic practice—spanning painting, drawing, printmaking and site-specific installation—draws from her lived experiences to explore the psychological effects of dislocation. In her 2019 exhibition “This Does Not Authorize Re-Entry” at the Craig Gallery in her now-home of Dartmouth, Shi reflected on 10 years of immigration limbo. She combined symbols and text from immigration paperwork with imagery from her childhood living in the historic hutongs (neighbourhoods made up of narrow alleys) of Beijing. Abstracted figures with layered, textural surfaces are frozen mid-stride, suggesting movement with no fixed place. The recognizable chevron-like arrows of passport pages were multiplied in vinyl and snaked across the gallery walls. Shi’s installation was a direct response to the space, a skill undoubtedly developed through years of adaptation and adjustment: “As a temporary resident, I had to respond to the changes in my environment constantly. Whenever I began to feel more settled, a warning voice always reminded me, ‘You’re not here forever yet.’” This precarity prompted Shi to work with paper and soft materials that can be easily rolled up, stored and transported. “Looking back from a post-immigration perspective, I am starting to make peace with this experience and process it through my practice,” Shi explains. Her growing body of work acknowledges the nuances of immigration, understanding it as “a continuous living experience rather than a means to an end.”

Jay Pahre, Piebald Undercoat, 2020. Copper-coated steel, aluminum and gauze, 68.6 x 53.3 cm.

Jay Pahre, Piebald Undercoat, 2020. Copper-coated steel, aluminum and gauze, 68.6 x 53.3 cm.

Jay Pahre

In the last two years, Vancouver artist and researcher Jay Pahre has turned his attention to the island of Minong, also known as Isle Royale, in northwestern Lake Superior. Minong, meaning “the good place” in Ojibwe, is the site of the longest-running study of predator– prey relations on the globe—a bizarre intersection of settler intervention, attempted preservation and ecological precarity. With his ongoing project Flipping the Island (2019–), Pahre approaches the myriad ecosystems on Minong as case studies to better understand queer and trans ecologies. “‘Flipping the island’ is the [colloquial] name for walking the island lengthwise and back again, but flipping is also the idea of something tipping over or changing sides, or shifting from one set of orientations to another.” The changing wolf population is exemplary of the island’s transitory ecologies; after wolves were first introduced in the 1940s, populations have continually collapsed and regrown due to inbreeding, disease or drownings in the island’s copper mines. In Guard Hairs (2019), one of the pieces from this project, Pahre folded copper-coated steel wires into loosely woven gauze to create a pelt of the portion of a wolf’s coat most responsive to atmosphere and affective changes. Pahre often turns to metal, electricity and conductivity as integral elements in his work, seeing them as metaphoric conductors or conduits for nonhuman relations. Pahre’s processes are repetitive and accumulative, be it walking the length of the island or threading individual hairs of a pelt, and his roving methodology pushes toward unfixed futures. “This is a speculative ecology, a transitory ecology, and an ecology on the move.”

Laura Grier, Process view of K’enetlé Ft. Cheezies & Chocolate (A Dene Break Up Poem), 2019. Lithograph, 45 .7 x 61 cm.

Laura Grier, Process view of K’enetlé Ft. Cheezies & Chocolate (A Dene Break Up Poem), 2019. Lithograph, 45 .7 x 61 cm.

Laura Grier

One day, while graining a lithography stone in the studio, Laura Grier found themself wanting to communicate more directly with their collaborator, limestone. The Délı̨nę First Nation artist’s printmaking process combines Indigenous methodology and traditional Dene knowledges. “I was really interested in something I call Spirit Methodology, but also a Spirit Printmaking methodology, that combines practice, labour, process, community, responsibility and spirit,” Grier explains. “All things have spirits, and they’re living beings. So I started having a conversation with the stone.” These conversations became the basis for Grier’s 2019 MFA thesis project at OCAD University, a series of lithographs titled Yǝ́dı́ı Kwǝ. (Yǝ́díı is the North Slavey word for “spirit”; Kwǝ is “stone.”) Through a series of performative actions and mark-making, Grier demonstrated human experience to Kwǝ, choosing to show, rather than tell, their experiences in love, heartache, sexuality, depression and Dene spirituality. In K’enetlé Ft.Cheezies & Chocolate (A Dene Break Up Poem), Grier mouthed the words of a breakup poem in North Slavey directly onto the stone, using the greasy combination of Cheezies and chocolate—Grier’s go-to in moments of heartbreak—to create a custom tusche. In sadae anele Idíikǫ́né, Grier’s vibrator bounces and rattles against the stone’s surface, resulting in abstracted jitters of black ink. For Grier, printmaking is more than a process, it’s ceremony: “It was kind of a way of giving back, and of communicating to something bigger than just this rock. This rock is a spirit, but this rock has history. Its history is land.”

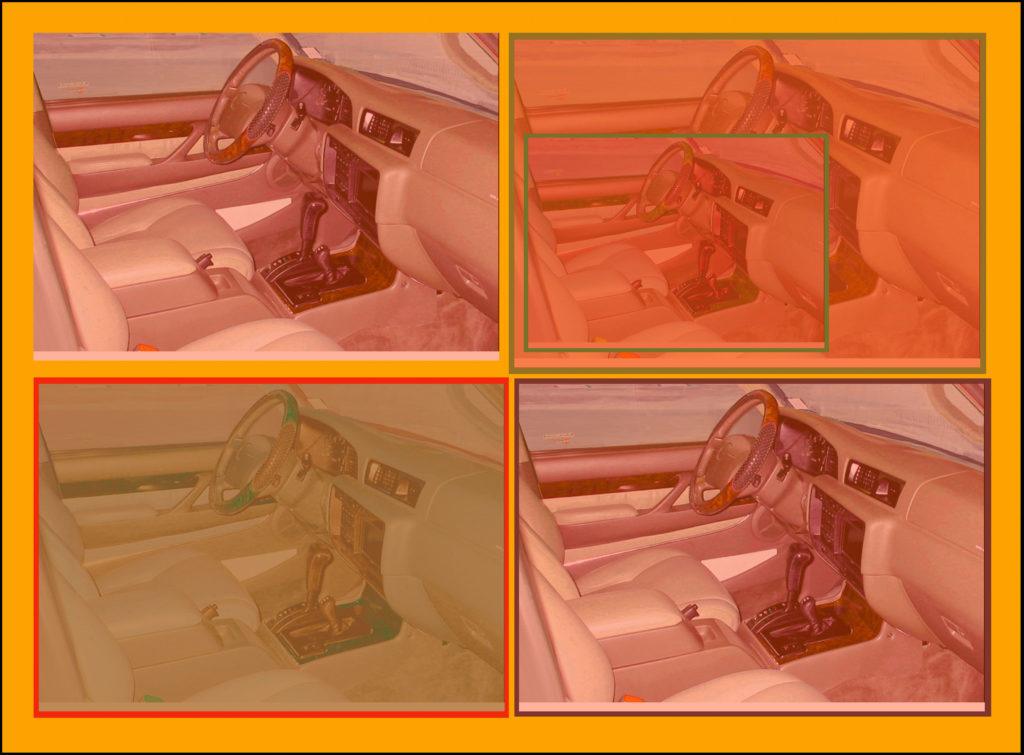

Derek Coulombe, 470 Interior, Plush and Heavy, 2020. Digital file.

Derek Coulombe, 470 Interior, Plush and Heavy, 2020. Digital file.

Derek Coulombe

“I want a 1996 Lexus LX 450,” writes Derek Coulombe. “I want it to be the year 1997.” The Toronto artist and writer excavates visual and textual oddities with subject matter as varied as alpine skiers and luxury SUVs to address nuanced concepts such as critical disability. Currently a PhD candidate in York University’s visual arts program, Coulombe mixes visual practices with autotheory and memoir to obliquely address his embodied experiences living with obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette’s syndrome. Through hyperlinks, visual and narrative interludes, and a creative usurping of academic citation, Coulombe embeds a sprawling practice of digital and archival excavation directly into his dissertation. One vignette is a 10-step manual on how to suntan interminably; another describes a sitting figure wrapped in layers of vintage ski gear, perspiring with no relief, an indirect metaphor for “complete stasis, a paralysis of rumination, cyclical thought patterns, and obsession.” Coulombe’s imagery has a purposefully mid-’90s aesthetic: to him, 1997 represents his prediagnostic period, before the onset of his symptoms. Cultural phenomena from the period have since become fixations. The Lexus LX series (a line developed in the ’90s to circumvent the threat of aggressive government tariffs on luxury vehicles imported from Japan) bore an unexpected correlation to Coulombe’s experience of Tourette’s: illogical excess born from constraint. “Tourette’s is like excessive energy,” he explains. “Your synapses are telling you to move your arm in a certain way, but it doesn’t have a function that correlates to the actual practical needs of being.” Coulombe’s manuscript extends his concept of “Tourettic Longing,” which is not hoping for an “able” body but rather for one without constraints. “I do not sit and pine after the normative,” writes Coulombe, “I instead imagine a disorderly bliss.”

Jagdeep Raina, Let me taste purple silk monsoons in these bathinda fields, 2020. Embroidered tapestry, Sainchi Phulkari on muslin, 45.7 x 50.8 cm.

Jagdeep Raina, Let me taste purple silk monsoons in these bathinda fields, 2020. Embroidered tapestry, Sainchi Phulkari on muslin, 45.7 x 50.8 cm.

Jagdeep Raina

Through research, collaboration and an expansive, interdisciplinary practice, Guelph artist Jagdeep Raina considers how historical memory can be captured, recorded and mapped onto materials. Raina examines patterns of migration from the Global South, mining both public and private archives to “resurrect lost histories through visual art and writing.” Raina is currently collaborating with friend and playwright Satinder Chohan on a project centred on the Green Revolution in Punjab. The 1960s agricultural framework introduced intrusive industrialized processes to India’s farmlands, eventually leading to widespread ecological devastation and an epidemic of farmer suicides. Raina restores the often-overlooked stories of families affected by the framework through a series of embroidered tapestries based on photographs from Chohan’s personal archive. In Blood money (2020), a mourning family sits on a small bed holding a photo of their son who died from suicide. In Moon garden punjabi birds. (2020), colourful silk threads depict endangered and extinct birds of the Punjab region. Traditional Phulkari patterns border many of these tapestries, a labour-intensive Punjabi embroidery practice whose associated livelihood was all but destroyed during the Partition of India—the violent relinquishing of British control over the country. “When I think about the histories of the impact of colonialism on the textile industry in India, it’s devastating,” says Raina. “So much of this craft has just been destroyed. As an artist, I’m interested in preserving [these practices]. How can I resuscitate them with my own material practice? There’s some hope in that.”

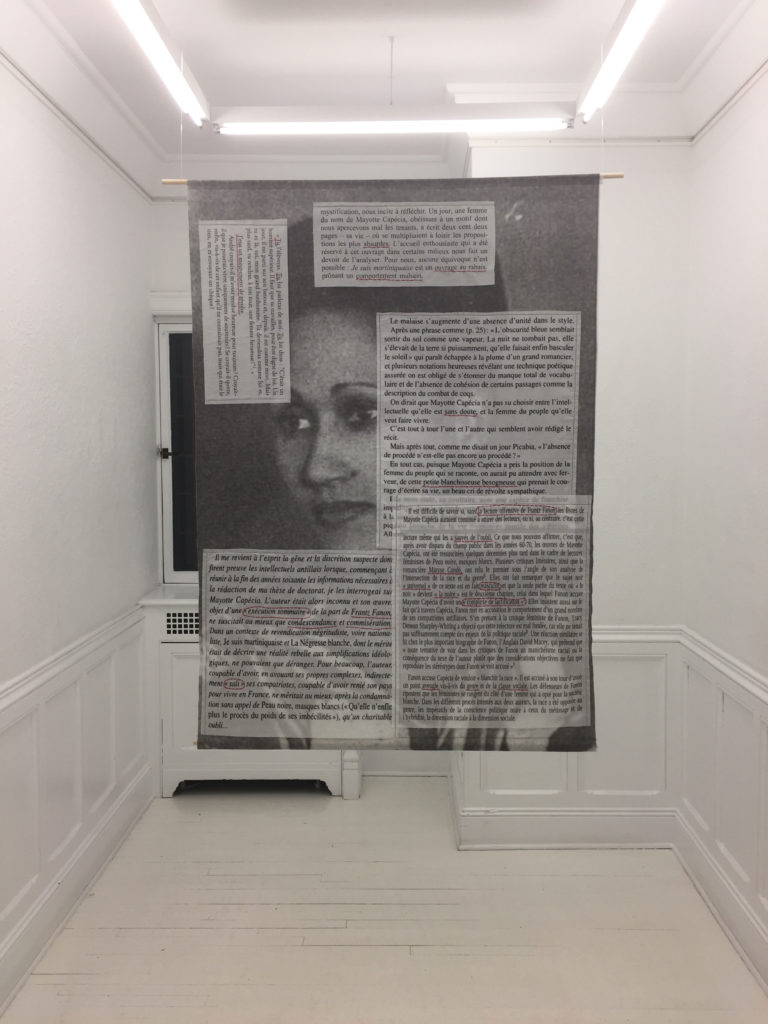

Michaëlle Sergile, De Capécia à Fanon (From Capécia to Fanon), 2020. Cotton fabric, acrylic threads and wooden supports, 1.2 m x 76.2 cm.

Michaëlle Sergile, De Capécia à Fanon (From Capécia to Fanon), 2020. Cotton fabric, acrylic threads and wooden supports, 1.2 m x 76.2 cm.

Michaëlle Sergile

“In French, the lexicon of weaving is highly connected to identity,” says Montreal artist Michaëlle Sergile. Sergile explores the possibilities of connecting text and texture by revisiting postcolonial theory through weaving. For her 2017–18 project Peau noire, masques blancs (Black skin, white masks), Sergile developed a complex coding system to translate French psychiatrist and political philosopher Frantz Fanon’s seminal text of the same name into eight large-scale hanging tapestries. Each line of text became a thread, and each chapter a tapestry. “The horizontal lines followed every sentence in the book in black-and-white thread, playing with the colours and words we use to describe people. Fanon was always using those words—‘black’ and ‘white’—so I’m questioning what they really mean.” To counter the monochrome of the weft threads, Sergile wove rich shades of brown and beige into the intersecting warp. With this introduction of material nuance, Sergile’s woven transpositions counter the stark binary of Fanon’s totalizing discussions of race. In a later project, De Fanon à Capécia (From Fanon to Capécia) (2018–19), Sergile focused directly on Mayotte Capécia, author of the semi-autobiographical novel Je suis Martiniquaise (1948) and a target of Fanon’s criticism. With the weaving of a unique tapestry, Sergile created a material tribute to Capécia’s underrepresented voice, as the author’s works were all but overwritten by Fanon’s dominant discourse. “I want to question history, I want to question archives,” Sergile explains, “to be able to see what we’re doing wrong today and what we can do for our future generations.”

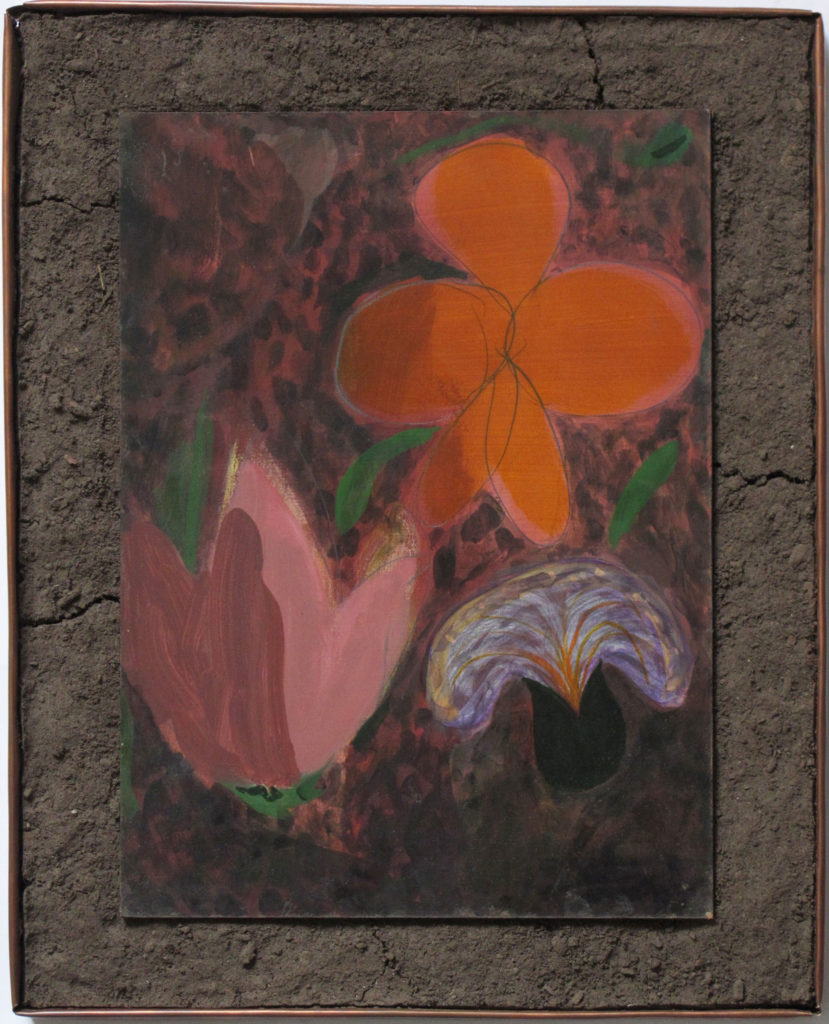

Cadence Planthara, untitled (flowers soil painting), 2018. Unfired foraged Toronto

clay, coconut coir, copper, acrylic, graphite and oil on board, 51 x 44 x 4 cm.

Cadence Planthara, untitled (flowers soil painting), 2018. Unfired foraged Toronto

clay, coconut coir, copper, acrylic, graphite and oil on board, 51 x 44 x 4 cm.

Cadence Planthara

“I consider my objects as functional,” Cadence Planthara says, but then, rolling her eyes, adds, “Well, what is function?” Her ceramics do function in obvious ways—vases hold flowers, bowls carry fruit—but they’re one-offs rather than traditional sets: sculptures that masquerade as cups, plates and vases with wobbly, idiosyncratic shapes. The Toronto artist studied ceramics and intermedia at NSCAD University, a pairing of craft and conceptualism that’s still present in her work. She describes her objects as sometimes intentionally “irregular or inconvenient…. If you can’t stack plates properly, it requires you to slow down in a particular way.” For a recent group show at Toronto gallery Pumice Raft, Planthara created an installation of ceramics, paintings and publications. For misc img (2017–20), iPhone photographs from the private Instagram account @misc_img were colour-Xerox-printed and perfect bound into three thick, block-like books. The account is an archive of diaristic vignettes, where we see glimpses of in-progress ceramics, objects held close to the camera and placid domestic scenes. “It’s a visual reference for me,” says Planthara, “but also serves as a memory aid.” Gaps in memory manifest materially throughout her practice: perforations reveal the insides of two- and three-dimensional works, while drilled holes are filled with objects like peppercorns and pearls. Pearls are a lunar object indicative of Planthara’s study of Western astrology, and peppercorns are a spice native to Kerala, India, her father’s place of birth. “If you make enough holes in something, is it still that same thing?” A recurring point of curiosity for Planthara: how familiar forms produce unfamiliar relations through the slippery boundaries of an object’s function.

Eva Birhanu, wear my hair, 2019. Cotton, 58.4 x 106 cm. Courtesy The New Gallery.

Eva Birhanu, wear my hair, 2019. Cotton, 58.4 x 106 cm. Courtesy The New Gallery.

Eva Birhanu

In her fibre and sculptural practice, Calgary artist Eva Birhanu examines the tokenization of Black and mixed women’s hair through autoethnographic weavings, tapestries and sculpture. Birhanu, of Ethiopian and Danish descent, explains how her long, curly hair often attracted unwanted attention from predominantly white students at the Alberta University of the Arts, her alma mater. “I started to home in on aspects of my identity that were often racialized, that I felt were being judged or singled out. My practice is about what other people see of me, not necessarily what I perceive myself to be, so I started to think about my hair.” In a recent exhibition, “you stare, i stare,” installed in the windows at The New Gallery in Calgary, Birhanu hung three weavings that, as the title suggests, confronted the viewer with their own gaze. In hair weaving 2 (2019), a clump of curly hair hangs on the surface of white, woven fabric. The disembodied hair imitates the profile of Birhanu’s back, provoking questions around what this token of identity means when removed from the body. In cake and wear my hair (both 2019), images of Birhanu stare defiantly from monochrome jacquard tapestries. “I wanted to take back my power with that stare, to say, ‘I can see you staring at me, I can see you tokenizing or objectifying me.’” During her BFA studies, Birhanu began experimenting with bronze, later creating a trophy-like cast of a long braid of hair; the weighty sculpture offers a talismanic homage to this charged aspect of physical identity. Birhanu has since cut her hair, saying, “I just wanted to take it all off, to not have that kind of weight on me anymore.”