“Cliff’s approach to life and to art was lighter than air, frictionless and fluid.” Artist and long-time friend Jan Peacock’s words capture the essence of what made Cliff Eyland, who passed away on May 16 at the age of 65, such an undeniably unique presence in the Canadian art scene over the past four decades. Trained at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in the early 1980s, Eyland’s conceptual calling card was the three-by-five-inch format file card, which he used throughout his career, from covert interventions on library catalogues to massive public art installations, most notably at Winnipeg’s Millennium Library in 2005 and the Halifax Central Library in 2014. Based in Halifax and later in Winnipeg, Eyland’s influence and generosity extended well beyond his own art practice—his website proves as much—as a curator, writer, educator, administrator, collaborator, mentor and community builder. As with his approach to life and work, his studio door was always open.

Concentrating hard on Cliff is the opposite of Cliff. Cliff’s approach to life and to art was lighter than air, frictionless and fluid. He never got stuck anywhere on anything. He had many pasts, some of which I was unaware of. Recently, Steve (Higgins) and I were at a lecture in Halifax and found ourselves talking with a woman seated next to us. Somehow she ended up telling us that she was married to Cliff “a long time ago.” I texted Cliff, forwarding her best regards. Ever at his phone, he instantly texted back, “Oh, lucky you! She’s lovely. Say hi for me. xo”

In fall 1982, Cliff sat at the back of the small, dark AV theatre at NSCAD, chatting and offering cryptic pronouncements as I flailed through my first semester of teaching. It was the Intermedia Seminar, and I was nonplussed (not for the last time) by how much NSCAD students already knew. At the same time, Cliff worked as a student assistant in the NSCAD library, but he was really more of an artist-in-residence there. He had quickly arrived at what would be the generative rules for a lifetime of production on three-by-five-inch surfaces, the dimensions of the standard library file card. His spacious hours in the library set the pace for and approach to that production: rule-based categories and constant immersion.

Years later, in Winnipeg, Cliff and I shared the backseat of Bill Eakin’s car, Wanda Koop riding shotgun, as we headed for one of many ritual lunches at the New Hong Kong Snack House. Cliff had a little lap desk he carried with him and throughout the car ride he drew constantly on his file cards, while still participating affably in the conversation. He was like a reliable employee. His drawing activity was as effortless as breathing. Breathing, on the other hand, became difficult.

When Cliff had business with bureaucracy, his ludic and visionary side surged. Certainly, he was reactive, but his reactiveness was always productive. He simply sidestepped institutional myopia and rigidity. When the scope of his direction of Gallery One One One (now the School of Art Gallery) at the University of Manitoba was questioned, he resigned and used a room off his own studio to open Library Gallery (L’Briary), where the rules were, basically, “no rules.” One of his long-term projects was Your Own Grad School with Jeanne Randolph, which was always serious, always a party. Cliff wrote, “Part of me regrets that artists don’t take up the freedoms the way I imagine [they] used to…. Are we allowed to have fun? (My Protestant art school training always said NO!”

Cliff returned to Halifax every summer to visit his family, and, whatever his feelings about his “Protestant art school training,” he always offered to present work and make studio visits with students at NSCAD, and always insisted on doing this for free. His 5,000-piece installation at the new Halifax Central Library in 2014 made him a local star and drew a fond crowd.

At the end of 2016, after years of deterioration from sarcoidosis, Cliff was awarded two new lungs. Cliff wrote to his many friends, “What a trip! I gotta count myself lucky. Docs thought I had a few months pre transplant, and now who knows—years and years maybe…. It is so strange to be able to think of the future.” His friend, Craig Love, called him “Miracle Man.” Appraising the vast array of daily anti-rejection medications that became part of his new life, Cliff said, “I’m so grateful to be able to take them…they say after a year rehab I’ll no longer be considered disabled. Meanwhile I’ll get back in the studio next week and enjoy my disabilities!” —Jan Peacock, with Steve Higgins and emails and texts from Cliff Eyland

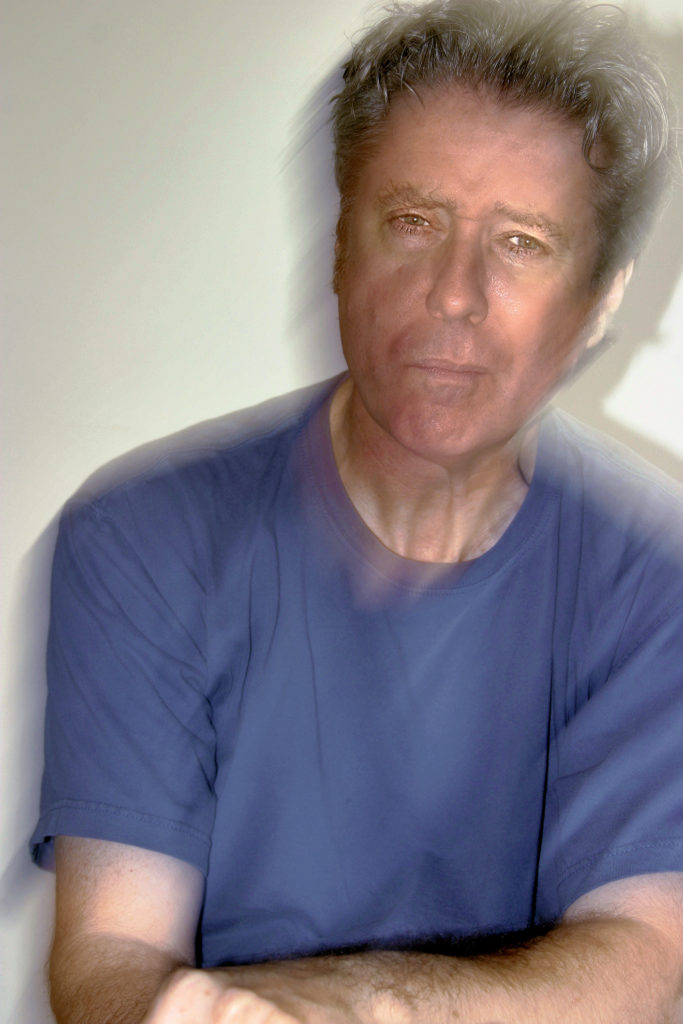

Cliff Eyland in his Albert Street studio, Winnipeg, June 13, 2005. "Just hanging out in the studio," notes William Eakin. "Cliff had a more or less 'open studio' policy and people were always dropping by and hanging out." Photo: William Eakin.

Cliff Eyland in his Albert Street studio, Winnipeg, June 13, 2005. "Just hanging out in the studio," notes William Eakin. "Cliff had a more or less 'open studio' policy and people were always dropping by and hanging out." Photo: William Eakin.

Cliff was a generous nexus for anyone who neared his orbit. Everyone who knew him formed their own “Cliff,” and I don’t think he minded this in the least. Like all good listeners he was not unlike a mirror, letting you talk yourself out in any way you saw fit. I would like to think that in the 22 years we knew each other, first meeting when I was a student and then becoming fast friends and colleagues, I had the honour of experiencing more than one Cliff. He was a consummate host whose studio, and later his exhibition experiment, Library, had the widest open-door policy I could imagine. Any passer-by could have a drink, a nibble or even play on the permanently set up mic/guitar/bass/drums. He was the king of hanging out, and a great cheerleader for whatever you were endeavouring to do. His own work ethic was amazing. I once drove a cargo van across the Prairies to Edmonton to install Cliff’s Meadows Library commission. Cliff drew on his three-by-five-inch file cards as we drove, while 1,600 more tiny paintings sat boxed up behind our seats beside our hard hats and steel-toed boots. (In the end, 600 paintings were installed.) The van was not insulated, which made it too noisy to talk, so instead of shouting we sang. This consisted mostly of a looping medley of Bob Marley songs. We sang the entire way there and back to Winnipeg, having more meaningful exchanges only while stopped; red lights had never been so delightful.

There was a time when we were in the same studio building in Winnipeg. Cliff would stop by my studio on the fourth floor before going up to his own on the fifth. He would come in and sit down to catch his breath from the stairs. We chatted as I worked or puttered around. As things (usually me) would get animated vis-à-vis our conversation, we would continue our way upstairs. More often than not I would begin priming his three-by-five panels while we chatted—may as well make myself useful and earn the beer or scotch that we most probably would share as we yakked away the afternoon. Sometimes this priming would turn into me mimicking Cliff’s process—painting “Cliffs”—friendly taunting that would also result in him painting “Craiggies,” mimicking my process. Eventually these shenanigans resulted in Cliff having a pile of my “Cliffs” set beside the chair where I would usually sit, something for me to work on if my hands got bored while we gossiped or theorized. Sometimes I would sneak one of my paintings into one of his towering piles, piles of many hundreds of paintings forming an urban metropolis. But by the next visit my forgery would be back in my pile or sitting on my chair. Cliff had a wonderful, bemused smirk that I became very familiar with throughout our friendship. When I went to his storage locker last week to take stock of the vast amount of work, I saw a banker’s box that had my name on it; inside were some of those sneaky little paintings of mine picked out for me one last time.

It was Cliff’s belief that if you were physically making art you were an artist, and nobody could stop you from being one, regardless of any art world success or praise. “They can’t stop me from doing this” was a kind of mantra that we would joke about…and boy did he mean that with all his heart. —Craig Love

Abzurb performance troupe portrait with Cliff Eyland and Tannis Kohut at Plug In ICA, Winnipeg, June 22, 2006. Photo: William Eakin.

Abzurb performance troupe portrait with Cliff Eyland and Tannis Kohut at Plug In ICA, Winnipeg, June 22, 2006. Photo: William Eakin.

Cliff and I met in the early 1980s when we were both students at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, a school recognized for its innovation, experimentation, research and development in the arts and design field. It was then that Cliff first used the three-by-five-inch file-card format (for which he’d become widely known) as a site-specific installation piece that took place in NSCAD’s library. This was a time before the widespread presence of computers and digital databases, so the card catalogue was our search engine. Cliff had approached the then–college librarian, John Murchie, for permission to do a piece, N.S.C.A.D. Library File Card Intervention (1981), incorporating the destruction of an art history textbook, History of Modern Art by H.H. Arnason. Cliff cut up the book to the same size as a standard library index card and then inserted these as subtle interventions into the card catalogue, and the art canon. I don’t recall if there was any deliberate attempt to have the images from the art history book relate to the information on the catalogue cards, but unexpectedly confronting these objects was disconcerting as you tried to connect the dots between your search and the random images cut from a familiar tome. This passive interaction/exhibition with an informed public—it was an art college library after all—shows the origins of an unconventional way of thinking that would plot Cliff’s course as an artist, critic, curator, arts administrator, advocate, teacher and friend to many. —Peter Kirby

Cliff Eyland as Mummer Snowman in an Abzurb performance event at Frame Exhibition Space, Winnipeg, May 12, 2009. Photo: William Eakin.

Cliff Eyland as Mummer Snowman in an Abzurb performance event at Frame Exhibition Space, Winnipeg, May 12, 2009. Photo: William Eakin.

Cliff and I were introduced so casually so long ago; I can’t remember exactly when, why or where. We were both living in Winnipeg, so it must have been 17 years ago. Typical of Cliff’s insatiable curiosity for everything said or written, I realized right away that he already knew what I had been thinking since 1980. In 2004, during my three-day performance at the University of Manitoba’s School of Art, I noticed Cliff sat in the audience with pen and paper, scribbling the entire time. He gave me several of those sketches. He gave sketches to hundreds of friends. He gave $20 bills to strangers who looked like they needed it. He also gave paintings to me. He gave paintings to hundreds of friends. Whenever we were together, like at his and his wife Pam Perkins’s place for dinner, my quest was to make Cliff laugh. Not hard to do. We shared what I suggested to him was “a merry nihilistic” attitude, which evokes a lot of wicked allusions to almost anything.

Besides our shared delight in hard liquor, Cliff and I conspired: our most ambitious project was Your Own Grad School. Cliff was fabulous at the administrative duties, about which I am too lazy to care. The project was based on the idea that university art education was getting out of hand. While an MFA/MVA degree could be an adventure, Cliff and I were appalled at the emergence of a PhD in studio arts. Cliff’s critique was pragmatic and economic. My critique was existential and psychoanalytic. Here’s our Your Own Grad School program: an artist-run centre “closes” the gallery for a month; the gallery is set up for as many artists as can comfortably work there as their independent studio; they pursue what matters to their practice at the time; for the final week, Cliff and I arrive to talk with each artist about aspirations, education, money and of course the work they’ve got going; if someone has a topic, we’ll all sit around and discuss it; if someone has curiosity about what Cliff or I do, we’ll sit around and discuss it. Never without beer; never without a bottle of scotch. At Modern Fuel Artist-Run Centre in Kingston, we even conducted a graduation ceremony: everyone failed. They failed because they were too smart, too independent, too imaginative and too educated already. I wrote these things directly on their diplomas.

Friends loved to wander into Cliff’s Winnipeg studio to sit around. Exhibitions he curated were on view. There was always beer or scotch. Then there were times when I’d show up to find Cliff and our friends Hassaan Ashraf and Armaghan Afghan sitting around, Cliff playing electric bass, Hassaan electric guitar and Armaghan tabla. “We need a songbird,” said Hassaan. The next week I’d return. “Yeah we need a songbird,” remarked Cliff. “Okay, okay, I’ll be your songbird,” I chirped. I can’t sing. I’ve never been able to sing. But I can warble words extemporaneously. Cliff said the name of the band was Satan’s Chewtoys. We rehearsed every Monday. We enjoyed performing a few shows. It did get too hard on Cliff, what with all the interruption by infections. I can’t describe Cliff’s personality. I never tried to psychoanalyze him, even when he accused me of doing so. Cliff was like the 1960s—if you think you can accurately depict him, you weren’t there. —Jeanne Randolph

For details and to donate to the Cliff Eyland Memorial Scholarship at NSCAD University, click here.

Cliff Eyland in an early Abzurb performance (as William Eakin recalls: "Cliff had an idea for an absurd landscape intervention") at the Winnipeg Floodway, December 21, 2003. Photo: William Eakin.

Cliff Eyland in an early Abzurb performance (as William Eakin recalls: "Cliff had an idea for an absurd landscape intervention") at the Winnipeg Floodway, December 21, 2003. Photo: William Eakin.