In advance of the inaugural Toronto Biennial this fall, Canadian Art is publishing a weekly series of behind-the-scenes features from artists, curators and participants in which they discuss the research and processes that inform their practices.

This past June, the Toronto Raptors won their first NBA championship and the city was electrified by the team’s success. I still feel a tinge of excitement when I see a “We The North” pennant draped over a balcony, or a “We The North” t-shirt worn by a passer-by on the street.

Which brings me to narratives of place.

The genius of the “We The North” slogan is that it feels so innately true. Created by marketing agency Sid Lee and launched in 2014, “We The North” has generated a huge popular following even if it is, technically, farfetched. Does it matter that Toronto lies at the same latitude as Florence in Italy, or Nice in the south of France and is farther south than many US states? An article written by David Taylor (and published on the CityMetric website) succinctly puts it this way: “We think of Canada as a long way north—but half its population lives south of Milan.”

A couple of years ago, the artist Cauleen Smith visited Toronto from Chicago and remarked to me, “Wow, the sunlight really is different here.” In terms of latitude, the Canadian city is merely two degrees farther north than her hometown (a place where the idea of “South Side” has particular significance). But this fact matters little: my friend actually saw that the sun appeared differently in the sky because, as far as she was concerned, travelling to Canada actually meant travelling “up north.”

Narratives of place are powerful. This power extends to the ways we think; more importantly, it extends to the ways we perceive our surroundings. I have no doubt that the sun appeared differently to Cauleen’s highly attuned eyes. In his book Language and Myth, Ernst Cassirer wrote that “symbolic forms are not imitations, but organs of reality.” According to this view, narratives, which function as symbolic forms, do not represent a reality that precedes and exists independently of them. Rather, the stories we tell inform the ways in which we experience what counts as real in the first place. Form follows fiction…

I have been learning about the different symbolic forms—the organs of reality—that inform this place we call Toronto. As Anishinaabe/Ojibwa artist Bonnie Devine said last year during a talk for her exhibition “Circles and Lines: Michi Saagiig” at the Art Gallery of Mississauga: “This place has a history. It goes back longer than 150 years; it goes back longer than 500 years. This place has a memory and it has a voice. And if you listen, you will hear it.”

Bonnie’s words remind me of overlapping narratives. One familiar narrative, created only 151 years ago, calls this place “Canada.” A different narrative (this one being 500 years old) defines this place in terms of European history. Today, whenever we utter the words “Toronto,” “Mississauga,” “Ontario”—Mohawk, Anishinaabe and Huron words—much older narratives linger on our lips. I teach at the University of Toronto, in a building on Spadina Avenue—a street name that stems from the Ojibwa word Ishpadinaa, meaning “a place on a hill.” The learning process I have embarked on, as a teacher and an artist, is a process of listening to competing narratives.

Last December, in preparation for my project at the Toronto Biennial, I went to visit Laura Ten Eyck. During the 1990s, she had been part of the artist-collectives’ scene in Toronto; these days, she is an expert dealer of rare maps in New York. I asked her to teach me about these wonderfully rendered narratives of place. The experience was eye-opening.

Laura showed me a map made in 1677 by Giacomo Giovanni Rossi, which designates the region that is now southern Ontario as “N. du Petun” and “Hurons.” A different map, made in 1719 by Henri Chatelain, names this place as “Teiaiagon”—a Seneca settlement at the Humber River, a short bike ride from my home near High Park. Another map by Jacques Nicolas Bellin in 1773 depicts it as “Fort Toronto Francois,” the French Fort Rouillé, on today’s CNE grounds. Finally, a map published in 1798 by J. Stockdale in London, calls it “York,” the British appellation before the city’s citizens petitioned to rename it “Toronto” in 1834.

What do these maps tell us? What do these divergent ways of envisioning what is ostensibly the same place have to say? What tensions in our perception do they engender?

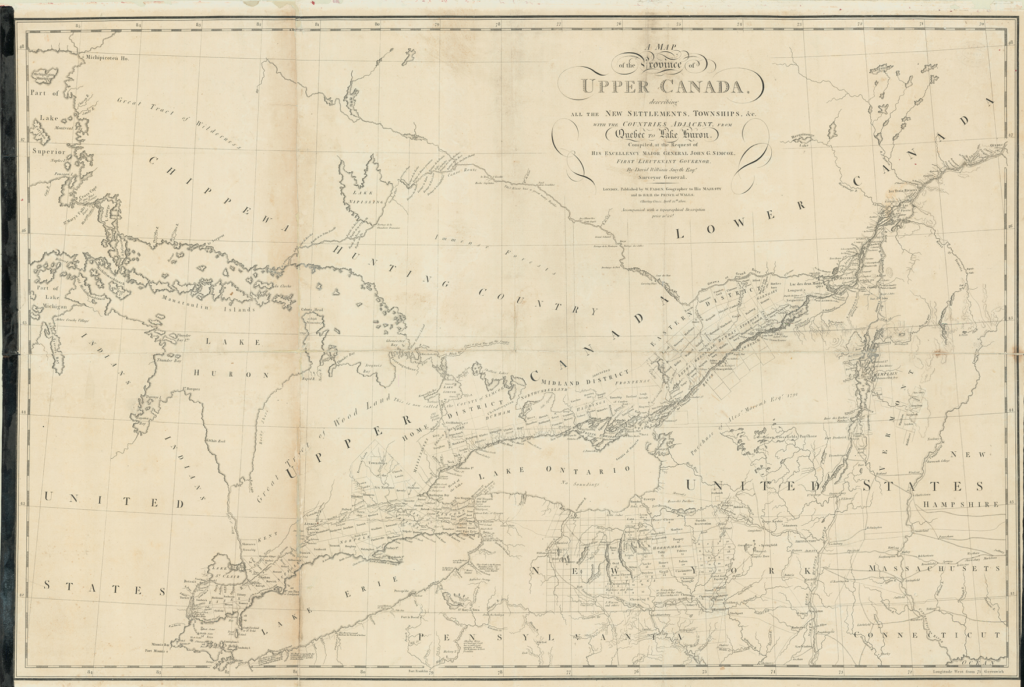

David William Smyth, Map of the Province of Upper Canada, Describing all the New Settlements, 1800.

David William Smyth, Map of the Province of Upper Canada, Describing all the New Settlements, 1800.

Back in Toronto, I stumbled across one particularly intriguing map: David William Smyth’s Map of the Province of Upper Canada, Describing all the New Settlements, from 1800. It was made soon after the massive influx of Loyalist refugees escaping the American Revolution. Writing about this time in his book, “The Municipality of Toronto: A History,” Jesse Edgar Middleton notes:

The system of land grants approved by the Governor of Canada for Loyalist army men provided that a field officer should receive 5,000 acres, a captain 3,000 acres, a subaltern, 2,000, and a private soldier, 200 acres. Generous grants were made also to loyalists who had not been in active service but whose dislike of republicanism drove them across the Canadian Border. Nine years after the close of the Revolutionary War [in 1783] the population of the present Province Ontario was over 12,000, though as yet no permanent settlements have been established at Toronto.

Smyth’s map depicts what must have been a frantic demographic transformation due to what, in today’s parlance, might be called the “caravan of migrants” coming from south of the border. An astonishing 60,000 United Empire Loyalists fled to British North America, today’s Canada, followed by an additional 30,000 Late Loyalists. This dramatic transformation appears in the map as a series of loosely rectangular allotments along the north shore of Lake Ontario, which correspond to frequently hastily drawn treaties between local First Nations and the British Crown. The rectangles on Smyth’s map are data-visualization graphics depicting colonial settlement. Notably, one space west of where I now live is excluded from these colonial allotments. It is named, “Mississagues,” which is to say that it is depicted in the map as Indigenous territory.

The website of the Mississaugas of Credit First Nation tells me that, after Smyth’s map was made, the greater part of this Indigenous land was subsequently subject to two treaties: the Head of the Lake Treaty, No.14 (1806) and the Ajetance Treaty, No.19 (1818). The settlements now found within this huge territory include the cities of Oakville, Mississauga, Brampton and Milton. Middleton describes what the settlers who moved into such a territory would have done upon arrival:

The first production of a settler was ashes for the making of potash. The trees, now so valuable, were enemies in those days, to be attacked without quarter. While the first clearing was made with the axe, fire was used afterwards. The dried underbush was set alight and the hardwood was thus charred and killed. The dead trees were brought down by the axe or the winds of winter and then followed the logging bee. All the neighbors assembled with chains and oxen and made enormous piles of the dry logs. These were fired and the ashes saved for sale. There was a social side to these logging bees, with whiskey only 2 shillings a gallon, and with a dance beginning at nightfall.

The rectangles on the map correspond to the clear-cutting of land—”to be attacked without quarter”—during the process of colonization. I now live on this clear-cut and colonized territory. The map’s very paper—its “body”—survives into the 21st century from this significant moment in time.

Luis Jacob, 'The Weed-whacker’, Sterling Avenue, Toronto, 2018.

Luis Jacob, 'The Weed-whacker’, Sterling Avenue, Toronto, 2018.

Maps are narratives. They function as “organs of reality” to the extent that they inform the ways in which we perceive the places they envision. And photographs are narratives too. Last summer, I made a photograph titled, ‘The Weed-whacker’, Sterling Avenue, Toronto (2018), which depicts a young man at work. He stands on a small rectangle of concrete adjacent to the parking lot of a confectionery factory. Evidently, he has been instructed to kill the weeds that have, against the odds, managed to take root there. What voices, what tensions do we perceive when this image is placed alongside Smyth’s map?

Bonnie Devine reminds us of the human impact of colonization:

They threw everything at us, and our grandparents and our great-grandparents. They threw everything they knew to rub us out—and we are here. And we have our stories; we have our faith; we have our teachings. Everything that they could do was insufficient to destroy us. We are the seeds of that. We carry that, and it’s not going away.

Symbolic forms inform our eyes. When we compare different narratives of the same place, the tensions generated by their divergent visions allow us to consider, perhaps for the first time, how partial our perceptions always are. The comparison itself becomes a new symbolic form—a new “organ of reality” —that allows us to reconsider what we had previously taken to be innately true. The tensions it engenders connect us to a political dimension: the sense in which each narrative is in alliance with, or in struggle against, overlapping narratives. As we witness these tensions, whose frameworks—whose viewpoints—do we choose to adopt, to inform our own sense of what is true about this place?