Conversations around gender, sexuality and sexual agency for Indigenous Peoples are not new. From ancestral teachings to songs to visual culture to birthwork, sex is tied to our ways of being. And it is safe to say that discussions of sex, gender and sexuality are becoming increasingly normalized with the rise of celebratory discourse surrounding sexual positivity within our collective nations. Particularly with the shift to digital and online platforms, representations of sexual empowerment are growing quickly while stigma and shame are, arguably, on the decline. We see sex in popular Indigenous-led TV shows and movies, paintings, Two-Spirit drag events, music, erotic literature, photography—hell, even beadwork. Personally, I love to see it. But the presentation of Indigenous sexual expression always leads me back to Indigenous burlesque and different forms of what might be considered lowbrow erotic performances (such as striptease, pole dancing and even drag). How does this type of visual storytelling benefit our communities, and what does body sovereignty mean for Indigenous Peoples? I can only speak on my own behalf: as an urban Anishinaabekwe residing in Miskwaagamiwiziibiing (Winnipeg), it is not my goal to pan-Indigenize concepts of sexual representation, but rather to start a dialogue about reclaiming and honouring our sexual autonomy.

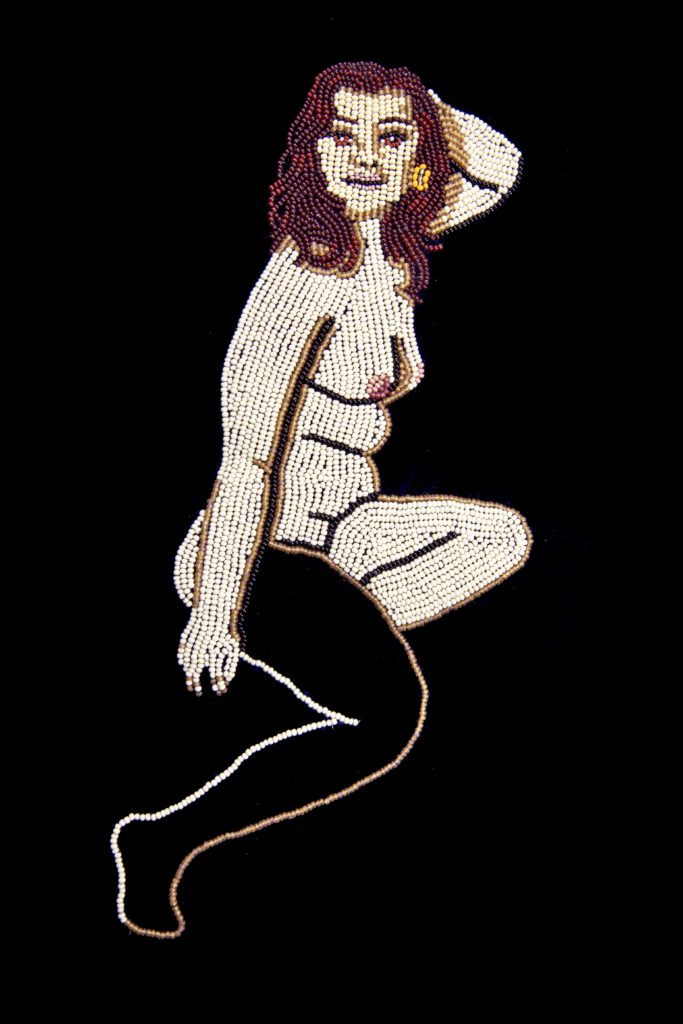

Jessie Jannuska, Aapiji ozaagi'aan ookomisan, 2020. Seed beads, thread, velvet attached to board. Courtesy the artist.

Jessie Jannuska, Aapiji ozaagi'aan ookomisan, 2020. Seed beads, thread, velvet attached to board. Courtesy the artist.

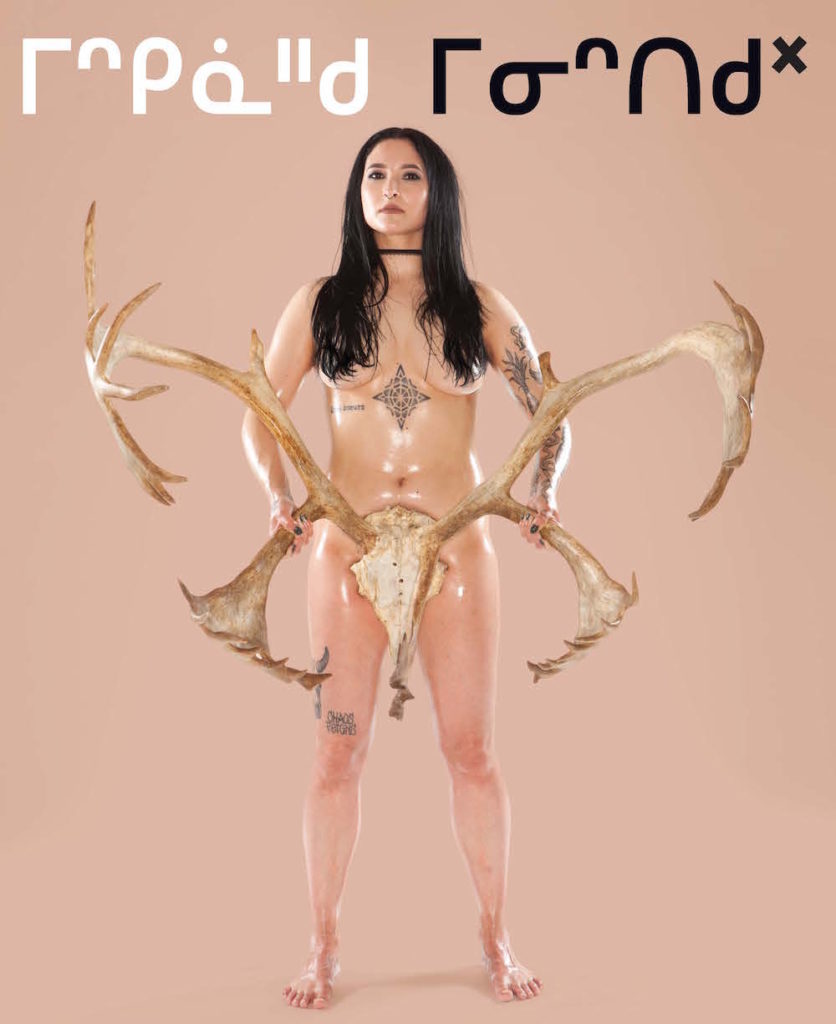

My initial experience with openly expressing myself as a young queer Indigenous femme started on the cover of Kinship, the Summer 2017 issue of Canadian Art. Edited by powerhouse scholar and author Jas M. Morgan, the issue featured a photograph of me on the front cover, mostly nude , by multidisciplinary artist Dayna Danger for their Big’Uns series (2017-ongoing). I distinctly remember the day that photo was taken, with Danger massaging baby oil into my skin while upbeat rave music pounded in the background. I felt cared for and safe in my vulnerability—a remarkable sensation that I can only describe as kinship intimacy. I never knew that that photograph would change my perspective as a timid Indigenous woman. In the months leading up to the photo shoot, I quietly began working as a receptionist at a local pole dance studio. I say quietly, because I grappled with internalized misogyny and shame around the sexual liberation of the Indigenous woman’s body, which was followed by the looming disapproval that I expected from community members and peers. But the cathartic experience of training my body to move sensually—to express lust through movement and to dance for me and me only—was and continues to be indescribable. Until that point, I never really felt like my body was mine; instead, it felt like a vessel whose worth was measured by its Indigenous pedigree in relation to the Indian Act and reduced to an object through the Western patriarchal gaze. Pole dancing was my introduction into my sexual empowerment journey, which led me to fully appreciate Danger’s desire to consensually redirect and shift inaccurate narratives around the naked Indigenous body in their photo series. When that photograph circulated on newsstands and was met with delight by art aunties, Elders, my mother and colleagues, it unearthed a carefree and rebellious spirit in me. The strength of our relationship—between Morgan, Danger and me—became visually apparent the moment I held that caribou rack and stared sternly at the camera lens: I came back to myself, physically and spiritually, through the support of my kin and community.

The Summer 2017 issue of Canadian Art, themed on Kinship, bears a cover image by Dayna Danger titled Adrienne (2017). The cover line reads “On Turtle Island” in Cree.

The Summer 2017 issue of Canadian Art, themed on Kinship, bears a cover image by Dayna Danger titled Adrienne (2017). The cover line reads “On Turtle Island” in Cree.

I often think about the ways Indigenous Peoples are finding methods and platforms to celebrate sensuality through a community-engaged lens. Tipi Confessions is, according to its website, a “live storytelling show on sex, sexuality, and gender, featuring performance and anonymous audience confessions. [It] highlight[s] Indigenous, decolonial, political, humorous, creative, feminist, queer, and/or educational perspectives.” These performances span poetry, erotic literature, burlesque, sex education, comedy, theatre and music. The showcase is produced by three Indigenous women, Kim TallBear (Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate), Tracy Bear (Nehiyaw’iskwew from Montreal Lake Cree Nation) and Kirsten Lindquist (Cree-Métis). Tipi Confessions creates a safer space for Indigenous Peoples to express their sexual desires and perspectives around sexuality and gender identities, while normalizing the liberation of the Indigenous body through visual narrative and imagination. “Storytelling can be expressed through words, like oral storytelling, spoken word, poetry, but also through movement—for example, through burlesque or other performances. It’s like connecting with the unspoken, the core seed within you,” explains Lindquist. She considers herself a “newbie” burlesque artist, performing under the clever moniker of Pemmican Milkshake as part of the Beaver Hills Burlesque Collective in Alberta. In an interview, she spoke about her own burlesque practice as an Indigenous woman and academic, and the act of performance that allows her to become more present in her body. “We are all entangled in colonialism and capitalism, but I want to always bring it back to Indigenous knowledge at the core of thinking about the relationship with the body. I think about spirit or landscape as the largest circle that holds everything, and I always reflect on wâhkômâkanak [which] in the Cree language [means] ‘we are all related.’” Indigenous sexual sovereignty requires a community of support to destigmatize representations of desire and pleasure. In many ways, the organizers are building a network of Indigenous People who are tired of living in shame of their bodies, shame that is counterintuitive to our very beings. Our ancestors would never have wanted us to live in disconnect. “Tipi Confessions is a site where we can support body sovereignty, and I think that it’s a vibrational effect. If you think about throwing a rock into a pond, and the sovereign body is at the middle of these sites, then we ripple out to create a relational network. That’s where I’m going with the intersection between performance and body storytelling and then our spheres of governance with Indigenous communities.” Lindquist highlights an important element of body sovereignty for Indigenous Peoples and builds a foundation for us to encourage sexual expression to maintain autonomy over ourselves and our communities. The ripples in the pond remind me of our vibrational effects on the people around us: not only are we centring self-love starting at the body, but we are also extending love out towards our nations as a whole. Accountability is inherent in what Tipi Confessions does—it serves the community in many ways. With each event they host, they send a message that shows us that sexual and body sovereignty is attainable for Indigenous Peoples.

Pemmican Milkshake, 2018. Photo: Jun Kamata. Courtesy Kirsten Lindquist.

Pemmican Milkshake, 2018. Photo: Jun Kamata. Courtesy Kirsten Lindquist.

“I just never saw myself on stage. When the [burlesque] revival started in the ’90s and early 2000s, it was very centred around the white idea of retro beauty, which in itself is super problematic,” says Lauren Jiles, also known as Lou Lou la Duchesse de Rière. She’s Kanien’kehá:ka from Kahnawá:ke and a staple in the Indigenous burlesque community, winning numerous pageants and accolades internationally. “If you’re not white, then you’re exotic, and that’s something that really needs to be questioned, even still. I felt like it was a defiant act to get up on stage because I really didn’t see myself on any stages.” Jiles spoke about the lack of representation of Indigenous performers and how that impacted her early years doing burlesque, highlighting the fact that Indigenous women are either misrepresented or erased completely. “It’s frustrating growing up and not feeling like you fit the standard of beauty because we don’t see ourselves in movies or on stage. I feel like people might see burlesque as trivial sometimes, but I really think it’s important, especially because sexuality is such a big component of our well-being and our mental health.” The body, spirit and mind are connected, and Jiles personifies this through her lighthearted nature. She laughs lots during our interview, acknowledging that humour is one of the many ways her community works through healing trauma.

Lou Lou la Duchesse de Rière, 2020. Courtesy Lauren Jiles.

Lou Lou la Duchesse de Rière, 2020. Photo: George Dimitrov. Courtesy Lauren Jiles.

Lou Lou la Duchesse de Rière, 2020. Photo: George Dimitrov. Courtesy Lauren Jiles.

“The stripping sensation from the Mohawk Nation,” begins Lou Lou la Duchesse de Rière’s burlesque performance tagline. “You stole her land, and now she’s going to steal your heart.” Humour allows Jiles to reclaim her narrative through storytelling and comedy in her performances, or as she calls it, “satirical sexual pageantry.” “We are the best storytellers. In my community specifically, we deal with everything through humour, and it wasn’t until much later in life that I realized that we deal with so much trauma through joking and comedy. This is my journey, and this is what I’m supposed to be doing. I love it. It’s silly to think about [it] as a profession, but I am basically a sexy clown, and I get paid to do something that I think is intrinsically powerful, but also ridiculous and opulent.” And while Jiles describes her practice as comical, there’s a tone of sincerity and pride in the ways she’s able to challenge racism and misogyny in her artistic practice. There’s an incredible strength that emerges when she redirects harmful misconceptions of the Indigenous woman and reclaims her sexuality in the meantime. That is the power of Indigenous burlesque—it’s an accessible medium that pushes people to understand that we, Indigenous Peoples, are worthy of experiencing and exhibiting lust and pleasure. And through that, we are establishing that Indigenous bodies are autonomous and sovereign outside a heteropatriarchal and colonial world. “I once received criticism that told me I was contributing to the fetishization of Indigenous women and putting us in danger. And I just thought, ‘Would your grandmother let anybody talk to you like this?’ I am a Mohawk woman and I come from a long line of very strong, opinionated women that don’t listen to what men have to say. I want to take my story back. I want to take ownership of my body.” Jiles reminded me that Indigenous burlesque performers not only radiate sexual agency to set a precedent, but also to maintain their own authority in a world that has robbed them of that. She said, “I would not operate from a place that isn’t a place of power.” Sexual and body sovereignty is not a new concept to Indigenous Peoples; there are generations of ancestors who have fought for self-determination of gender, sex and sexuality. Members of our own respective communities have been pushing for these conversations for years while rejecting the histories that stole Indigenous People from their bodies. We owe it all to them. Indigenous burlesque not only reconnects our spirits to our bodies—it also frees them.

Lou Lou la Duchesse de Rière, 2020. Photo: Marisa Parisella. Courtesy Lauren Jiles.

Lou Lou la Duchesse de Rière, 2020. Photo: Marisa Parisella. Courtesy Lauren Jiles.