The theft happened September 4, 1972. It was Labour Day; the same day Canada’s hockey team won game two against the USSR in the Summit Series. One is remembered in volumes; the other, barely at all. The story as I’ve found it goes like this: Just after midnight, a man wearing climbing spurs scaled one of the trees on the property between the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts and the Church of St. Andrew and St. Paul to access the museum’s roof.

He then lowered a ladder to two men waiting below. The trio entered the building through a skylight that was under repair, which had left its security alarm disabled. They descended inside from the third-storey rooftop by sliding down a 15-metre length of rope.

Moving around the second floor, the intruders encountered a security guard either in or near the kitchen. When the guard didn’t immediately comply with their orders, one thief fired two blasts from a shotgun into the ceiling. The other two guards on duty heard the noise and responded but were overcome, and the security staff were bound, gagged and left in a lecture hall on the first floor. The guards later described to police two men with long hair wearing ski masks and armed with guns. One spoke French and the other spoke English. They heard the voice of a third man, who also spoke French, but they never saw him.

The thieves spent 30 minutes gathering paintings and artifacts. They’d selected a few dozen canvases off the walls, but when an alarm on the side entrance was tripped, they fled out the door with what they could carry—39 pieces of jewellery and 18 paintings, including works by Corot, Courbet, Delacroix, Brueghel the Elder, Rubens and a Rembrandt then valued at $1 million. Museum officials estimated a total of $2 million in stolen property.

Then-curator of decorative arts Ruth Jackson, who was among the first museum staff to report to the scene, found the gallery ransacked: shattered display cases, torn backings and many-hundred-year-old frames cracked to pieces. The stack of paintings left behind contained a Picasso, an El Greco, two Goyas, a Renoir and another Rembrandt. “With what they’d proposed to remove,” Jackson later told the Gazette, “it was just like they meant a general clear-out of the museum.”

The Skylight Caper is regarded as the largest art theft in Canadian history. Forty-seven years later, it remains unsolved. No charges have ever been laid. Two items—one of the two stolen Brueghels and a pendant—were returned within months of the crime, during initial ransom negotiations. Nothing else has since resurfaced: not inadvertently brought to auction, not intercepted in the transmission of stolen goods, not discovered during a police raid at the hideout of some criminal kingpin. And, as far as I can tell, no one is searching for them anymore either.

The curious thing about this theft is that as it greys, so do its details. First, the paintings vanished, and then as memories fade, witnesses and suspects depart, locations transform and records languish, so does the crime itself. Even our understanding of what exactly was taken shifts in absentia. When my editor asked if I might like to look into this, handing over a list of the stolen works collected on his desk for the better part of a decade, we thought: “Wouldn’t it be wild if we found a painting?” The challenge, it turned out, was to find anything at all.

Baptiste-Camille Corot, The Dreamer at the Fountain, 1855–63. Photo: MMFA.

Baptiste-Camille Corot, The Dreamer at the Fountain, 1855–63. Photo: MMFA.

Jan Brueghel the Elder, Landscape with Wagon, n.d. Photo: MMFA.

Jan Brueghel the Elder, Landscape with Wagon, n.d. Photo: MMFA.

THE WEDNESDAY prior to the MMFA robbery, there was another art theft less than an hour away—not front-page news but similarly sensational and Hollywoodish. On August 30, 1972, three hooded, armed men made off with a reported $50,000 in paintings from the Oka summer residence of Agnes Meldrum, who ran a successful trucking and storage business in Montreal. The robbers tied up the gardener, looted the place and climbed down what the Gazette described as a 600-foot bluff to a waiting motorboat docked below on Lake of Two Mountains. Again, two thieves spoke French, the other spoke English. At the time, the newspaper said police noted the similarities between the two crimes, though it was later concluded the thefts were unrelated.

For weeks after the museum robbery police surveilled a group of students from École des beaux-arts de Montréal (newly the Université du Québec à Montréal) who were known to museum staff. The tail was fruitless and eventually called off with no arrests made. Police also considered the possibility of an “inside job” and questioned museum staff. It was determined none were involved. In a 2010 interview, Bill Bantey, museum spokesperson at the time of the robbery, now deceased, told art crime writer Catherine Schofield Sezgin: “No one on the museum staff was involved. If there was any inside information, it probably emanated from the people working on the skylight repairs.” Police also questioned those workers and ultimately cleared them of any direct involvement.

The first call came within days of the crime. A nasally voice with a “European” accent, Bantey told Schofield Sezgin, instructed the museum to send someone to a phone booth near McGill University at Sherbrooke and Metcalfe. There, the museum security director answered a call, which told him to pick up a discarded cigarette pack from the ground nearby. Inside, he found a pendant, one of the missing pieces of jewellery. Communication between the thieves and the museum continued by phone and by mail. A brown envelope received October 26, 1972, contained a snapshot—or multiple snapshots, according to some accounts—of the stolen artwork all laid out together. The envelope was marked “Port of Montreal.” Perhaps a sign or maybe a bluff, since the city’s seaport was linked with the West End Gang, an Irish crime group active then and today.

The thieves asked for $500,000 for the return of the stolen goods. Then, they reduced it to $250,000. Museum director David Giles Carter, also now deceased, suggested that the group surrender a painting to prove they were still in their possession. Carter was instructed to check a locker at the rail station, Gare Centrale. He again sent the museum’s security director to investigate, who there found one of the panels attributed to Brueghel, Landscape with Vehicles and Cattle (there were conflicting reports about which of the pair was recovered, but museum staff assured me that this is the work currently in their holdings).

Shortly after, Carter arranged an exchange of cash for an additional painting. It was to be a set-up though, with an undercover cop playing the middleman sent to the meeting place with the money. But a Longueuil police cruiser, unaware of the operation, drove by the rendezvous and scared off the thieves, who called the museum the next day angry about the “trap.” Carter didn’t hear from them again for months.

In the early summer of 1973, a museum board member received communications from someone who said they had information about the paintings. A Montreal insurance adjuster named André DeQuoy spoke with the anonymous caller and thought the tip held promise. The museum agreed to put up $10,000 if DeQuoy would deliver the money to the caller. Journalist Paul Delean recounted the episode on the 10th anniversary of the theft for the Gazette: DeQuoy set off one afternoon around 2 p.m. with an envelope full of money. He went to the downtown phone booth the caller had specified. From there, he was lead to other phone booths at Blue Bonnets horse racing track, on St. Laurent Boulevard and at the Henri-Bourassa Metro station. DeQuoy crisscrossed the city, shuttling between 11 different phone booths by 4 a.m. He was finally instructed to leave the money at the foot of a sign in a vacant lot on St. Martin Boulevard. He returned to the phone booth near the Henri-Bourassa Metro station, as instructed, where the paintings’ whereabouts were finally to be revealed to him, but the phone never rang. He went back to his office and a call came through at 8 a.m. The caller told him the artwork had been left at a motel in Laval. Police combed the building, but didn’t find a thing.

As far as published accounts of the various recovery efforts go, the story ends here. Writing in the Gazette in 2007, Bantey said: “negotiations eventually broke down,” and that “Police say there have been no developments in the investigation.” My request for information from Montreal Police eventually produced a small, highly redacted incident report that, despite its scantiness, included details diverging from the accounts I had read: The skylight rope was double the length reported in newspapers; I saw no mention of spurs (though it does mention a tree appearing to have been climbed); 14 paintings were left behind in the museum, not 18; and the total value of stolen property was significantly larger than reported: $5 million. The stolen Rembrandt alone, it said, was worth $1.75 million.

Eugène Delacroix, Lioness and Lion in a Cave, 1856. Photo: MMFA.

Eugène Delacroix, Lioness and Lion in a Cave, 1856. Photo: MMFA.

Peter Paul Rubens, Head of a Young Man, n.d. Photo: MMFA.

Peter Paul Rubens, Head of a Young Man, n.d. Photo: MMFA.

I ARRIVED in Montreal to bad news from the museum. Not only would I not be allowed onto the roof to see the skylight, but I also wouldn’t have access to the Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion, where the 1972 robbery took place, because it was under construction. The recovered Brueghel and Rubens’s The Leopards (late-17th to mid-18th century), the painting purchased by the museum in 1975 using a portion of the $1.9 million insurance settlement for the stolen artwork, were in off-site storage.

I spent the afternoon in the museum’s archives department reviewing newspaper clippings and examining glossy photographs of the missing paintings. It struck me, for as much as I’d read about the theft, I’d never seen images of the art that was stolen. Not every piece anyway and never larger than a thumbnail. I’d driven 500-some kilometres compelled, apparent to me only then, by a bodiless idea of “stolen art,” not because I knew the paintings or liked them, but for a whole bunch of unexamined notions about what’s valuable. It felt foolish—but somehow illustrative.

The next morning, I met Alain Lacoursière for breakfast at a downtown Montreal athletic club. The retired Montreal police detective who specialized in art crimes was the subject of a recent book and Radio-Canada TV documentary, both titled Le Columbo de l’art. He now runs a consultancy offering services like artwork appraisal and authentication. Through the 1990s, Lacoursière worked on the Skylight Caper case on the side, out of his own curiosity. His superiors told him not to waste time or resources on it. As Schofield Sezgin told me, he is perhaps the only person who has looked at the police file and will talk about it.

Asked when he began investigating the MMFA theft, Lacoursière’s response was immediate: “Nobody investigated that theft.” That is, he doesn’t believe there was ever a real investigation. According to him, at the time, two investigators worked on the case, then closed the dossier after just a year. “They don’t have any clues, any information, any suspects,” he said.

We went over details he previously told Schofield Sezgin: how police knew about the climbing spurs from the marks on the tree and how contrary to newspaper reports, the robbers did not flee in a panel truck; they left on foot, running down Sherbrooke Street. Also, that there were two men, unfamiliar to museum employees, who had been going up to the rooftop on the building across the street to smoke and watch the construction on the roof opposite. They had said they were from the museum. “And what about the security guards?” I asked. “Were any still alive? Anyone I could speak with?” Unlikely. He’d heard three or four years ago that two had died and that the third had Alzheimer’s.

I scanned various theories with the retired detective. For instance, a Le Soleil article from September 5, 1972, about the MMFA theft, mentions the leader of a Quebec nationalist, theocratic and separatist party who was convicted in 1970 of stealing 28 paintings from the Musée du Québec. A Crown witness testified the artwork had been stolen to finance the party. The decision, however, was overturned two years later. What are the chances some such group was responsible for the theft in Montreal?

“No, nothing like that,” he said.

What is the likelihood the paintings were destroyed? (This was a concern mentioned by current MMFA director Nathalie Bondil.) Lacoursière again rebuffed: “I never had any information or clue like this.”

What about the theft in Oka five nights prior? Was it somehow related?

“No. They asked the Sûreté du Québec to compare, and it doesn’t match with the description of the crime here. They excluded that very fast.”

Are the paintings buried somewhere, like the 1933 MMFA theft where the robber hid the artwork in a sandpit then took strychnine in his jail cell so he wouldn’t have to stand trial? There was a story like this, Lacoursière said. Long after the robbery, a drug dealer in British Columbia informed police that the MMFA’s pictures were buried on the property of a lawyer’s country house somewhere south of Montreal. But the lead lacked detail. And it was thought the man was likely speaking baselessly, desperate to lessen his own sentence.

And what about the art school students? The police followed them and nothing came of it, Lacoursière said. There was one student, though, he cannot forget. In 1998, at an exhibition vernissage, he met a man who had attended École des beaux-arts de Montréal around the time of the theft, but who was not included in the police investigation. We’ll call him “Smith,” as Schofield Sezgin has in her reporting. The pair got on the topic of art thefts. Smith knew a lot about the 1972 museum robbery—details Lacoursière wasn’t sure were ever made public. Lacoursière set a trap and mentioned the “steel rope” the intruders used to drop into the museum. Smith corrected him: “No, no, no, it was a nylon rope.” Smith was right.

Lacoursière visited Smith a number of times at his home near Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu. He collected classic cars and auto paraphernalia, especially early Bugatti, the French racing brand. Smith loved art. He knew every painter, Lacoursière said, and had extensive knowledge of the history of art in Quebec. He owned a large carpentry shop, the business from which he made his living. The detective found it odd Smith had the money so shortly after art school to purchase a home and a wood shop—apparently, without a mortgage. Smith seemed evasive. “Oh, my family is very rich,” he said when Lacoursière inquired. In 2007, while filming the Radio-Canada documentary, the detective offered Smith a $2-million cheque to tell him where in Smith’s garden he’d have to dig to find the paintings. Smith laughed and invited the film crew inside for coffee.

They kept in touch. A few years later, in 2011, Lacoursière says he received an email from Smith, containing a link to a Mercedes-Benz commercial where a briefcase gets stolen from a bank vault, a high-speed chase follows, then the contents of the case are revealed: it is a stolen Da Vinci. Smith died two years ago, Lacoursière said. He doesn’t think Smith had the paintings and he doesn’t think he masterminded the crime, but Lacoursière maintains, even despite the apparent lack of evidence, that it is possible Smith was one of the three who committed the theft.

So who ordered the heist? “Probably the West End Gang or the Italian Mafia,” Lacoursière said. “Or the Italian Mafia hired the West End Gang.” Some organization—that is his best guess. The artwork gets sent to the Columbians or the Russians, he said. “They exchange cocaine, they exchange arms for a quarter of the value of the painting.” A $10 million Picasso, Lacoursière speculates, might be worth $2.5 million in drugs.

So where does that leave Montreal’s missing paintings? According to Lacoursière, they’re likely in Mexico or Central America, or maybe South America. “Maybe 20 years ago,” he said, “I saw a picture of a house in Columbia. It was a living room and I saw a stolen painting from France. I asked my boss if we could have a warrant, and Interpol told me, ‘No, the police there work for him.’ It’s probably all the stolen paintings around the world that decorate those houses.” The theory sounded like a cliché to me—a stereotype of criminal Latin America. But only one of us had spent decades investigating art crime, and it is what he contended.

Nearly a half-century after the theft, though, police are no closer to finding what was stolen or those who stole it, Lacoursière said. In fact, they might be further away. When he first picked up the 20-year-old file in 1993, “it was missing a lot of pieces,” he said. Two declarations had vanished. Tips were investigated but improperly filed; information had been trashed as a result. At some point, everything left in the dossier was transferred to microfilm. The last time Lacoursière viewed the film, it was in poor shape. “Very bad quality,” he said. “Probably now, we can’t see anything.” Even the record of the crime is disappearing.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Landscape with Cottages, 1654. Photos: MMFA.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Landscape with Cottages, 1654. Photos: MMFA.

FROM LACOURSIÈRE’S athletic club, McGill was only a few blocks away. At Metcalfe and Sherbrooke, where the pendant was recovered, there were no longer any telephone booths. Nor was there evidence any ever existed, though you could imagine payphone-sized things once standing roughly in the footprints of the public art that now occupies two corners.

I walked through a steady rain to the city’s central train station. Commuters, office workers and others ducking the weather packed its food court at lunch hour. It’s a maze of walls drawn from counters like Saint Cinnamon and Jugo Juice, and vendors selling Tandoori chicken, Italian sandwiches or sushi. I doubted this much resembled the train station where the stolen Brueghel was dropped off. I wanted to find the lockers. Past a florist, an electronics shop, a Couche-Tard and two banks of coin-operated candy dispensers, which looked like the oldest things around—no lockers. I circled the concourse searching for a spot travellers might lock away luggage, where someone might conceivably have stashed a 400-year-old painting. But no such spot revealed itself. Another piece missing.

I was due back at the museum archives, but stopped first at the parkette between the church and the gallery. Its gate was locked. Just beyond, you could see the trees, including a few that did indeed reach up past the museum roof. But no one was able to tell me which was the tree. Even the skylight—I’d shown Lacoursière an old black-and-white image on my phone that I’d thought pictured it. But he said he’d have to see the police file again. He was pretty sure the room beneath it was used for administration now, whereas the museum, also not entirely certain, thought it was likely the skylight over their temporary exhibition space.

I returned to the archives because, though they are technically no longer part of the collection, the museum maintains files on the stolen artworks. They contained items like provenance documentation, conservation reports, loan records, scholarship and correspondence regarding the individual works. Reviewing the same folders, Schofield Sezgin had found notes on at least a handful of the 17 missing paintings suggesting the artist attributed was not the work’s true creator. Regarding Jan Davidsz de Heem’s Still Life with a Fish (date unknown), for example, a 1951 letter from the Netherlands Institute for Art History proposed it was more likely the work of Willem van Aelst, another Dutch Golden Age painter. As for the other stolen de Heem, Still Life: Vanitas (ca. 1635), a French art historian suggested it was better attributed to Evert Collier, based on a strikingly similar painting in the collection of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen in France. In other letters: The man in Thomas Gainsborough’s Portrait of Brigadier General Sir Robert Fletcher (ca. 1771) was wearing the wrong uniform for the sitter named in the title; François-André Vincent’s Portrait of a Man (late-18th to early-19th century) may have been a copy of a Vincent belonging to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Even the Rembrandt bore an asterisk. Reproduced on a note card were the words of Rembrandt expert Abraham Bredius upon studying the MMFA’s Landscape with Cottages (1654): “Probably right, but it has something which alarms me; I have the same uneasiness about the attribution.” Other scholars expressed similar doubts. The same locale appears repeatedly in works both by Rembrandt and his pupils. A more recent publication, titled Rembrandt the Printmaker, attributed Landscape with Cottages to a “Follower of Rembrandt.” Inside the folder, I found an exchange with the National Gallery of Canada about having the panel analyzed, but the final report—whatever it discovered—was not included.

Just as scenes important to the crime had transformed, time also refigured what was stolen. After the Brueghel was recovered, a German art historian specializing in the family’s work found its style inconsistent and its signature all wrong; its credit was changed to “Unknown Flemish Painter after Jan Brueghel the Elder.” School of, circle of, studio of, after—this was the language of authenticity devised for the suspect and the disingenuous.

The cruelest twist was this: The authorship of the painting the MMFA purchased in 1975 with its insurance settlement—Rubens’s The Leopards, said to be the largest in a Canadian collection—has also since been questioned. Julius Held, a scholar of the artist, counselled the purchase. And it hung prominently in the gallery. Then, in 1992, Marie-Claude Corbeil of the Canadian Conservation Institute found The Leopards could not possibly be by Rubens. Microscopic analysis of pigment from the lips of the pictured blonde child, the leopards’ mouths and the nymph’s red drapery showed a type of vermillion believed to have been invented more than 40 years after the artist’s death. The painting, now attributed to “the workshop of Peter Paul Rubens” by the MMFA, has not been exhibited since.

The problem of misattribution is by no means specific to Montreal. It is a problem, mostly unspoken, for every major museum collection. “The true crime in art,” Schofield Sezgin told me, “is the sale of art in the secondary market.” Unless you’re buying work from the hands of the artist, it can be very difficult to be sure what you have. This is true, she said, of historical and contemporary art alike.

Courtesy Library and Archives Canada (OCLC NO. 43834165, Montréal-Matin, p. 3)

Courtesy Library and Archives Canada (OCLC NO. 43834165, Montréal-Matin, p. 3)

I DECIDED to leave Montreal through Oka. I couldn’t see the skylight or the phone booth or the train station locker, but if there’d ever been a 600-hundred-foot cliff like the one fabled in that lesser crime, I’d be able to find it. From the car, I spoke with retired FBI agent Robert Wittman, who founded the bureau’s national Art Crime Team and today works privately in art recovery. By his estimate, he has recovered USD$330 million in stolen art and cultural property—a career record that makes him something of a Hall of Famer in the business.

Wittman said, generally, the people who perpetrate art thefts on the scale of the MMFA robbery are better criminals than businesspeople. “They don’t know that the true art in any art heist is not the stealing, it’s the selling.” And that’s because “there’s really no black market in stolen paintings,” he said. There are no end buyers. He’s never heard of a dope dealer who’ll give away cocaine, which has a solid street value, for boosted paintings, which have none. In three decades of investigations, Wittman has never encountered a true “Dr. No” collector—the wildly rich, amoral aesthete who orders up stolen paintings for his private enjoyment. Though he has played him undercover.

I pulled up to the address I’d found for the old Meldrum residence, a grand, three-storey chalet trimmed in cheery green and red. It was evidently now a retreat home for isolated seniors. And it did appear to overlook a rather large cliff with a lake beneath. I went inside and introduced myself to the first person who seemed concerned I was there. Mildly puzzled, he called into a back room for another volunteer, Chantal, who spoke English. I told her about the 1972 Montreal Museum of Fine Arts theft and the 1972 Meldrum theft and asked if she knew anything about the history of the place. She stepped away and returned with a pamphlet titled “Historique,” sat down and began to read it to me, translating from French.

“Meldrum, here it is,” she said. “And here, about the theft.” According to the pamphlet, in the early 1970s, the gardener was, one night, held up by thieves at gunpoint. This was consistent with the accounts I’d read elsewhere. “The paintings from Madame Meldrum’s collection were stolen by these thieves,” she read, “and found extremely damaged, several months later, behind Fairview mall in Pointe-Claire.”

“They were found?” I confirmed. Yes, behind a mall in Pointe-Claire, she repeated. In all of the retellings, in all of the newspaper clippings, I’d never heard the Meldrum paintings were recovered.

“And then it says: Among the stolen artworks, there was a Rembrandt.”

“A Rembrandt?”

“That is what it says.”

This certainly hadn’t been reported elsewhere.

Chantal led me out through the backyard, where they were decorating for Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day. There was indeed a cliff. Not 600 feet tall, but tall enough that a night-time climb with an armload of paintings sounded remarkable. Below, there was the lake where a getaway boat could wait.

I took the ferry from Oka to Hudson. Speculations boiled inside my head. If Agnes Meldrum had a Rembrandt, perhaps the crimes were more alike than I’d been led to believe. Or was the Rembrandt not hers? Was it possible that the MMFA’s Rembrandt was so badly damaged that it was dealt with quietly? I felt like if I tugged hard enough at this thread, a painting by Rembrandt—or whomever it was by—might resurface.

A half-century after the theft, police are no closer to finding what was stolen or who stole it. In fact, they might be further away. Two declarations had vanished. Tips were investigated but improperly filed; information had been trashed as a result. Even the record of the crime is disappearing.

BACK HOME, I couldn’t find any newspaper stories about the recovery or the Rembrandt. Nor could the organization that runs the retreat locate where they’d gotten the pamphlet information. Oka’s historical society, the likely source, was closed for the summer and not returning messages. Sûreté du Québec told me, because it happened so long ago, they had no files on the initial Meldrum robbery or the recovery, neither at Oka’s police station or in provincial archives. But I’d gotten ahold of Agnes Meldrum’s great nephew Tom Filgiano, who’d run the family business after his father, who’d himself run it after Agnes. In his first email, he sounded cagey—and reasonably so—but he agreed to talk.

The same morning I interviewed Filgiano, I was granted access to Interpol’s stolen art database. The MMFA’s 17 paintings were still listed among the 50,000-plus missing works worldwide, so if any restitution had happened, Interpol hadn’t been informed. Filgiano said that when he read my email, it felt like he was hearing about the events for the very first time. Then he spoke with members of his family and began to remember.

“Mrs. Meldrum was like my third grandmother,” he said. He would spend weekends in the summer at her Oka home. “She was an avid collector of virtually anything that was beautiful.” And her house was full of antiques, he said.

He would have been 18 when the robbery happened. The newspapers got it mostly right, by his family’s account, except for the $50,000 figure. He and his siblings inherited Meldrum’s collections, and, in 2010, all of her paintings—what was stolen as well as a number of others—were appraised: the total value “might have been $50,000,” he said. And the pamphlet was right about the recovery, though he’s not sure about the part where it says they were badly damaged, because he doesn’t recall his family having anything fixed.

And then there was the matter of the last line, the one about the Rembrandt. There was definitely no Rembrandt, he said. He’s never heard anything about a Rembrandt. Meldrum had no understanding—or care—for who the masters were, Filgiano said. She didn’t collect that way. “I think she was a graduate of the Popeye school of art: I knows what I likes and I likes what I knows. And by the way, most of us are like that.”

So where did the idea originate that among Agnes Meldrum’s paintings recovered from behind a shopping mall in suburban Montreal, there was a Rembrandt? Filgiano has no idea. And, as long as the pamphlet’s sources remain unknown, neither do I. The detail dangles tantalizingly, though. Nested in the footnotes of the mystery, another mystery.

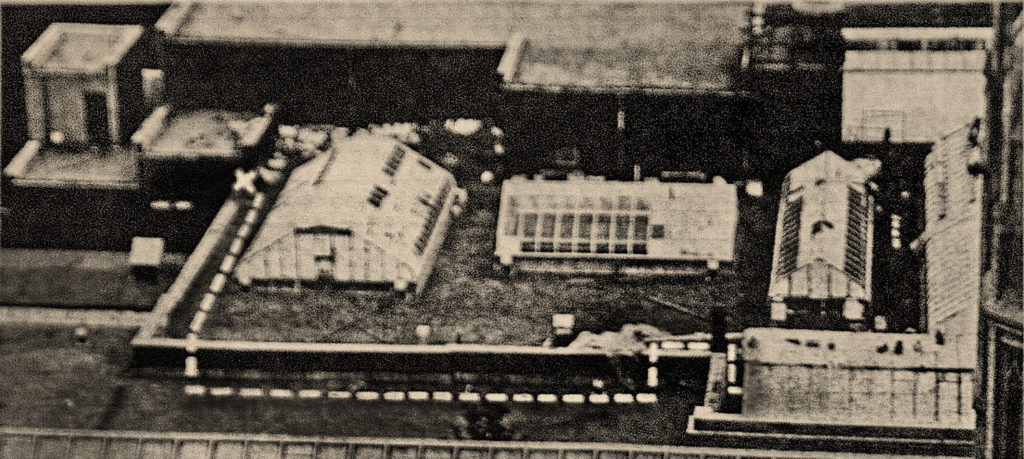

An illustrated photo published in the Gazette on September 5, 1972, indicates the point (marked “X”) where the thieves gained access to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts rooftop. They then made their way to the skylight under repair, where they entered the museum. Photo: Jean-Pierre Rivest, The Gazette.

An illustrated photo published in the Gazette on September 5, 1972, indicates the point (marked “X”) where the thieves gained access to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts rooftop. They then made their way to the skylight under repair, where they entered the museum. Photo: Jean-Pierre Rivest, The Gazette.

MANY HAVE told me how the story ends: In 100 years, 50 years, a decade, a month, perhaps even by the time this story has gone to print, one of Montreal’s missing paintings will turn up at an auction somewhere in the world. Most art recoveries happen when the party holding the property tries to monetize it. The major auction houses are committed to the restitution of stolen goods and so the painting will be returned to its legal owner, which, at this point, is a group of insurance companies.

Until then, the story is stuck. And those few still hoping to unspool it must wait. Meanwhile, it disintegrates from the other end. So some refuse to idle. Filmmaker Maxime-Claude L’Écuyer’s forthcoming feature based on the 1972 MMFA theft turns to fiction to advance the frame. His film begins at present, when the still-missing Brueghel painting surfaces at an auction house in Belgium. This re-opens the case for a veteran Montreal art detective, who works alongside a young conservationist to detangle the painting’s course of travel and determine who perpetrated the crime as well as the whereabouts of the other missing artworks.

The project is called Pentimento, L’Écuyer said, for all the layers uncovered when the surface is stolen away: things like authenticity, cultural patrimony, notions of value, as well as a deep sense of loss. At Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, site of the largest-ever unsolved art theft, the stolen paintings’ empty frames hang on the walls as a reminder. In Montreal, there is no such memorial—increasingly, there isn’t even a memory of it.

L’Écuyer began the film because he felt the story was in danger of disappearing completely. Retelling it “keeps it alive,” he said. The idea reminded me of something Schofield Sezgin had said: she approached the story like a conservator, by which she meant, mindful of those who would work on it after her. It is a useful way to regard our job. I told the story as I found it, recording the damages, repairing it gently where I might. And I hope I helped whoever tries next.