Our experience of reality is mediated by our senses, thus creating a worldview that is contained within the restrictions of human perception. “Logics of Sense” is a two-part exhibition presented at the Blackwood Gallery that curator Christine Shaw describes as “examin[ing] sense-in-the-making.” Showcasing mostly video work, the exhibition asks visitors to reflect on the manner in which they collect information about the world, whether it is directly through the senses, or through technology that allows us to experience phenomena beyond that of human realms. The video works are projected onto large rectangular structures that break up the gallery space, like a labyrinth organized into intimate viewing spaces. With an interest in the representation of sensing, the works highlight diverse perceptions, frames of reference, networks and disciplines to present interpretations about the relationships we have with each other and nonhumans.

"Logics of Sense 2: Implications" (installation view), 2019. Courtesy Blackwood Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

"Logics of Sense 2: Implications" (installation view), 2019. Courtesy Blackwood Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

The first part, exhibited from September 4 to October 19, challenged its visitors to “perceive ourselves sensing,” and asked us to recognize how social and biological habits of perception are not universal, but rather specific to human geographies, histories and politics. The show highlighted the limits of our sensory experience with works that allowed visitors access to realms of sensory data outside of human capacity, especially sound, through technological mediation. Ursula Biemann’s video Acoustic Ocean (2018) is a stunning sound encounter where the visitor can listen to the multiple soundscapes accessible to its protagonist: an aquanaut, performed by Sámi activist and singer Sofia Jannok, who uses different listening instruments to hear the Arctic Ocean. As the aquanaut puts on her headphones, visitors hear the seascape; as she takes them off, they hear the quiet sounds that surround the Lofoten Islands in Northern Norway.

Ursula Biemann, Acoustic Ocean (video still), 2018. HD video with stereo sound, 18 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.

As technology helps us understand other ways of sensing and communicating, Acoustic Ocean brings to mind questions of sovereignty. Who has the access and the right to speak and be heard in their native environment? The SOFAR channel—a layer of water deep in the ocean where sound waves travel at a minimum speed—is what many whales use to communicate with each other, sending messages across vast underwater landscapes. Biemann’s video states that humans discovered the channel in the 20th century through submarine warfare, negatively affecting whale communities. The ocean is a largely acoustic space where its residents rely on water as the material medium for sharing messages, and noise pollution created by ships on the surface and in the depths of the sea overwhelms this communicative network. The video describes a whale coming up to the surface and singing a “canto of impermanence,” reminding us that we humans share in the bio-infrastructures of sound, and are thus responsible for making sure our activity doesn’t prevent others from using these mediums of communication.

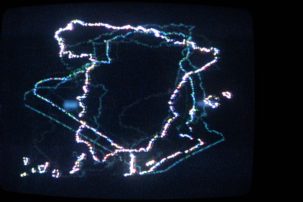

Susan Schuppli, Atmospheric Feedback Loops (installation view), 2017. 35mm vertical film transferred to HD video, stereo sound, 17 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist and Blackwood Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Susan Schuppli, Atmospheric Feedback Loops (installation view), 2017. 35mm vertical film transferred to HD video, stereo sound, 17 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist and Blackwood Gallery. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Susan Schuppli’s Atmospheric Feedback Loops (2017) also examines sound. This work is presented as a vertical video projection that simulates the shape of an instrument used at the Cabauw Experimental Site for Atmospheric Research (CESAR) in the Netherlands—a tall pole that stands out against the flat Dutch landscape. The video follows two scientists who analyze climate and weather by observing “the complex behaviour of clouds, aerosols, radiation, precipitation, and [how] turbulence interact[s] with terrestrial events.” Set against visuals of CESAR, the video’s soundscape is composed using the sounds of the research instruments at the site. Scientist Arnoud Apituley says, “We look at the atmosphere, we listen to the atmosphere. Because we are humans, we have to interpret our measurements, so we like to make them audible or visible to ourselves.” He describes how, in order to gather useful data, scientists need to distinguish between signals and noise. “Noise is seen as a distortion,” he explains, “[when] we talk about noise in this concept, with ‘signal’ in comparison to ‘noise,’ then noise is something we don’t want.”

But what is noise? What is a signal? In making these distinctions we categorize certain sounds as desirable and useful, and the rest as excess, dissonance or obstructions. Thinking about the colonization of audible worlds, musicologist and scholar Susan Campos-Fonseca speaks about “sound dystopias” and the “constant noise of nature.” She posits that “noise is a total saturation of the self and of the state.” Can noise then be an expression of resistance? On October 12, in reaction to Indigenous-led protests against neoliberal policies, the Ecuadorian government enacted a curfew on the capital city of Quito, where protests were centred. The city responded using noise. People stepped out onto rooftop terraces, balconies and streets to bang on pots and pans. The cacerolazo, a protest tactic used this past month by demonstrators around the world, used noise to create a collective soundscape of resistance.

Mikhail Karikis, No Ordinary Protest (video still), 2018. HD video with stereo sound, 7 min 44 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Mikhail Karikis, No Ordinary Protest (video still), 2018. HD video with stereo sound, 7 min 44 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Mikhail Karikis, No Ordinary Protest (video still), 2018. HD video with stereo sound, 7 min 44 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Mikhail Karikis, No Ordinary Protest (video still), 2018. HD video with stereo sound, 7 min 44 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Earlier this year, in a lecture about noise and sound, Judith Butler argued that “some political demands sound like pure noise to whom they are directed.” In human realms, ideology and culture shape how we interpret what we sense, including other humans’ audible expressions. Presented in opposition to “peace and quiet” or to “proper music,” Butler reminds us that “noise establishes a critical outside to any regulated world of sound and meaning.” In Quito, protestors critically enacted noise “for peace.” In part one of Blackwood’s exhibition, Mikhail Karikis’s No Ordinary Protest (2018) explores a similar communal noise creation with a group of seven-year-olds in London, UK. The children in Karikis’s work discuss climate change and become full of agency through this discussion by creating noise. They create improvisational noise using toys, musical instruments, their voices, and by clapping. Karikis’s composition presents an affective and uncomfortable soundscape that brings attention to our inadequacies in combating climate change.

Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Dissolution (I Know Nothing) (video still), 2016. Two channel video with sound, 10 min. Courtesy the artists.

Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Dissolution (I Know Nothing) (video still), 2016. Two channel video with sound, 10 min. Courtesy the artists.

Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Dissolution (I Know Nothing) (video still), 2016. Two channel video with sound, 10 min. Courtesy the artists.

Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, Dissolution (I Know Nothing) (video still), 2016. Two channel video with sound, 10 min. Courtesy the artists.

Where the first part of the exhibition explored sound, the second part focuses on material and immaterial flows to showcase global networks of capital and of digital information. “Logics of Sense 2: Implications,” on now until December 7, posits that digital networks have “become our real-time exo-somatic sensory organ,” and asks, “What logic of sensation can be discerned from this feed of generic feedback and generalized noise?” Referencing the phrase “All that is solid melts into air” from the Communist Manifesto, artists Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen write, “All that is solid melts into flow.” Their two-channel video work, Dissolution (I Know Nothing) (2016), speaks to the flow of water, capital and material goods across the globe. Images of the vast ocean are juxtaposed with images of factories, where workers are shown enduring repetitive movements of labour. The movement and speed of global capital visualize continuous exhaustion and continuous production to service a desire for never-ending growth.

In contrast to capitalist notions of growth, Miles Rufelds’s video essay Two or Three Saprophytes (2019) explores the power of decay. Saprophytes are plants, fungi or microorganisms that, as the video describes, can decompose almost anything. The work presents the chemical compound benzene as a symbol of the industrial revolution and the development of capitalism. Benzene belongs to a chemical “tree” of coal-derived products, and has been used in everything from the first artificial dyes to after-shave lotion, detergents and plastics. By showing that saprophytes can decompose even benzene, Rufeld’s work poetically presents them as the decomposers of capitalism’s death.

Miles Rufelds, Two or Three Saprophytes (video still), 2019. HD video with stereo sound, 32 min 27 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Miles Rufelds, Two or Three Saprophytes (video still), 2019. HD video with stereo sound, 32 min 27 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Blackwood Gallery’s “Logics of Sense” presents the opportunity to recognize the politics of sensing that determine how we perceive ourselves, each other and nonhumans, and highlights how techno-science has made it possible to perceive on a global scale. The artworks call to mind how some perceptions of the world are championed over others, revealing this power and possible ways to resist it.

Quotes from Susan Campos-Fonseca are the author’s translation.

Ursula Biemann, Acoustic Ocean (video still), 2018. HD video with stereo sound, 18 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Ursula Biemann, Acoustic Ocean (video still), 2018. HD video with stereo sound, 18 min 50 sec. Courtesy the artist.