When Laura Aguilar died in early 2018, aged 58, I let my students know. When one inevitably asked what she died “of,” I took a moment before responding: “she died from being poor.”

Aguilar was notoriously undervalued by the art world. Despite having been active in her photography practice since the mid-1980s, Aguilar enjoyed only a handful of solo exhibitions during her lifetime, including her first major retrospective at the Vincent Price Museum in Southern California, which ran from September 16, 2017, to February 10, 2018, ending just two months before her untimely April death. Thankfully this retrospective produced an exhibition catalogue, titled Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell, which includes essays in which friends, mentors, students and scholars of Aguilar engage in the power of her work. This collection of texts, unfortunately, constitutes the majority of critical writing about her work; it is also where I receive my framing of her reception, addressed throughout this essay.

This is how Aguilar’s life is commonly narrated by the writers featured in Show and Tell: she was a working-class Chicana lesbian from the San Gabriel Valley region of Southern California whose auditory dyslexia inhibited her performance in traditional school settings. Consequently, Aguilar taught herself photography with encouragement from her brother. Her work is deeply vulnerable and personal, frequently incorporating and centring her own nude, fat body. And while these writers might acknowledge that Aguilar’s corporeality was significant to the point and power of her work, it is often considered ambivalent, additive, perhaps even reluctant.

Aguilar’s portraits of nude bodies in nature—many of them selfportraits— are rightfully her most circulated and praised images. These are the images praised as successes of representation for Latinas or Chicanas, for queers, disabled folks, working-class people, self-taught artists and more in Show and Tell. But the potential for pleasure in fatness seems to remain elided—perhaps due to Aguilar’s own ambivalent relationship to her fatness. In addition to her photography, Aguilar produced a handful of video essays in which she partially recounts this relationship, among other topics. In her contribution to the catalogue, art historian Amelia Jones includes an excerpt from Aguilar’s 1995 video essay “The Body”: “Voluptuous is a kind way to put it, but really I’m fat. I am not saying I like being this way. I have always felt a lot of anger about my size. My work is a way of coming to terms with my body, with learning to be comfortable with who you are. I have lost some weight but I would like to lose more. …I’m trying to be really honest about accepting my body.”

But these statements are certainly not and cannot be the final lens through which we consider the presence and incorporation of Aguilar’s body in her work. While I will not deny or attempt to recuperate the bodily dissatisfaction Aguilar expresses and Jones cites, I will complicate it: Aguilar’s antagonistic relationship to her own body is not exclusive to the fat experience. Importantly, Aguilar herself frames this dissatisfaction as particular to her gender, not her size: “it’s something that all women struggle with.” Yet Jones, and others, might consider these temporally specific ruminations in ways that ultimately foreclose the potential of Aguilar’s work—intentionally or not—through a totalizing consideration of her self-portraiture as a “negotiation of her own painful feelings about her body.” Perhaps, yes. But what else is there?

While Aguilar’s relationship with her body was complicated—as is most of ours—the meaningful, pleasurable possibilities her work offers for fat bodies are rarely engaged. Aguilar’s exploration into nude self-portraiture sprung from being stood up for a date, and while it is impossible to know from this historical vantage point if her body size was considered in her date’s actions or in her own reception of them, it is nonetheless notable that this common experience is the moment in which she turned the camera to her own body. Aguilar was clear about her motivations for pursuing nude portraiture: it came from a deep desire to find, in her body, the pleasure she saw denied so frequently. Regardless of the role Aguilar’s fatness played in her would-be date’s decision that day, she and her body were operating within a fatphobic culture that denied her—and continues to deny many fat people—affirmation, love, acceptance, care or pleasure. Aguilar’s photography was her method for offering these practices to herself. And Aguilar’s reception of her body, as well as the reception of her body by the writers included in Show and Tell, are informed by the same culture that actively denies the possibility of pleasure in fatness writ large. This is a cultural context of limited imagination that forecloses the potential of Aguilar’s portraits.

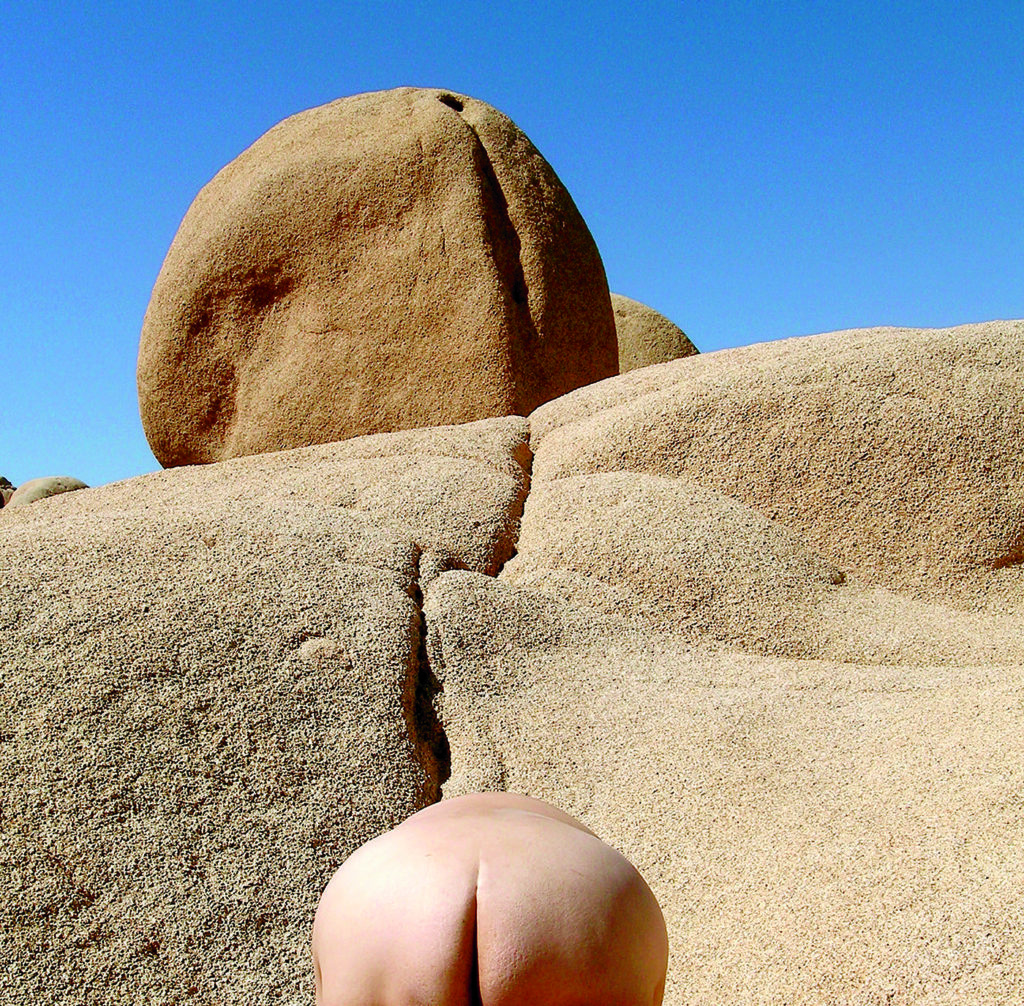

Laura Aguilar, Untitled (from the series Grounded), 2007. Archival pigment print, 43.1 x 55.8 cm.

Laura Aguilar, Untitled (from the series Grounded), 2007. Archival pigment print, 43.1 x 55.8 cm.

Aguilar’s placement of her own fat, nude body in nature challenges the viewer to recall and affirm the natural status of the fat body in a contemporary historical moment that has constructed fatness as an aberration

The cheeky pleasure of Aguilar’s response to criticisms of fatness as unnatural, among others, is evident, and can be read across her self-portraits. In her 2007 work Untitled, from the Grounded series, the viewer is met with a landscape image. Its focal point is split between two parallel objects, both large, smooth, round, beige and connected by a fault line in the desert earth. The object at the top of the image is weathered into a soft, smooth shape by millions of years of natural processes. Below is the artist, bent forward so that the natural curves of her soft, fat body mimic those of the earth, the dark canyon formed between her two fleshy buttocks invoked as an extension of the fault, which both physically separates and visually links Aguilar to her relative, the boulder.

Aguilar’s placement of her own fat, nude body in nature challenges the viewer to recall and affirm the natural status of the fat body in a contemporary historical moment that has constructed fatness as an aberration, another man-made intervention into the natural history of the world. It is a moment that insists not only that fatness should be eradicated but that it must be, for public health and safety. It is a moment that has developed artificial interventions to address the natural phenomenon of fatness: suppression of our caloric intake encouraged through diet pills and calorie counting, as if the innate forms of our bodies should be restricted with more manmade borders; surgical interventions placed under our skins like a pipeline, wrapping around, removing or replacing our stomachs completely; our bodies asked to shrink, to melt away like ice caps.

Aguilar’s commitment to, negotiations of and grappling with the pleasures in and offered by fatness—including her own—is referenced throughout her career, although it is also frequently overlooked, or collapsed with her other embodiments. Her practice persists against the shame, disgust and abjection imposed on her body by viewers, fans and critics of her work. Nature Self-Portrait #5 (1996) features the model-artist standing on a fallen, weathered tree, amid the bare branches that remain. Aguilar is again nude, with her back turned to the camera, unabashedly exposing the soft roll of fat that rests on top of her buttocks, as well as the soft ripples of cellulite that caress it. She stands triumphantly, with her arms raised above her in either a stretch or a praise, her limbs and fingers seeming to take their cue from the branches and twigs surrounding her. The imagined inanimacy of the tree is refuted by this mimetic performance, one of cross-species kinship.

Here, by placing herself not only among but supported by the forgotten, the discarded and left for dead, Aguilar reclaims her body as a natural phenomenon. But rather than herself succumbing to petrification—or assuming this process is inherent or inevitable—Aguilar calls attention to the life and vibrancy of the tree, to her own shared status in abjection and its intentional fabrication. Both in choosing a setting that might otherwise be overlooked or deemed too chaotic, messy, stagnant, depressing or dead for an artwork, and choosing to engage with it in this way that recuperates its lively potential, she also points to the joy, beauty, wonder and pleasure in her fatness—if only one knows where to look.

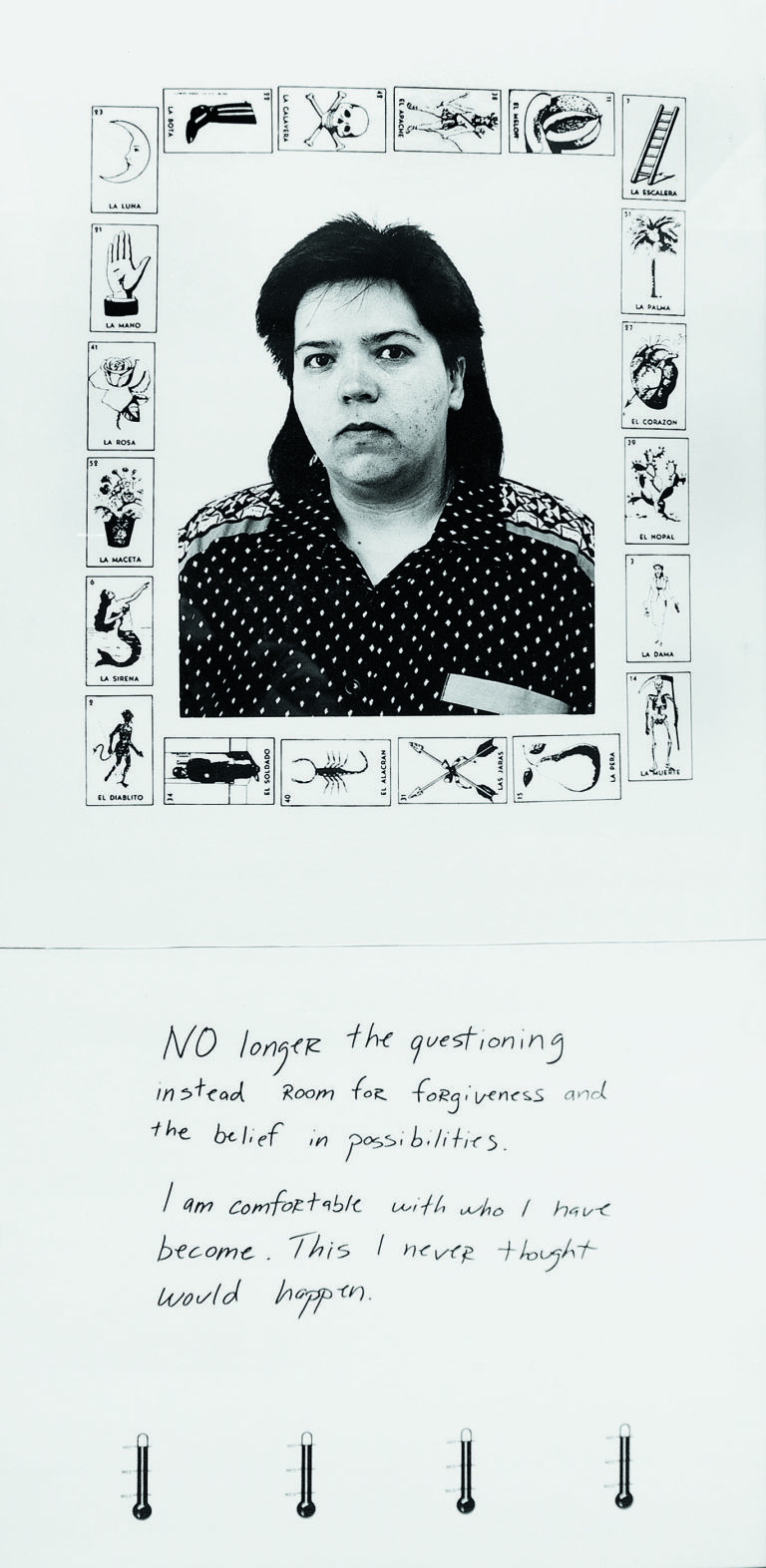

Laura Aguilar, How Mexican is Mexican (Part 3C), 1990. Gelatin silver print, 101.6 x 50.8 cm.

Laura Aguilar, How Mexican is Mexican (Part 3C), 1990. Gelatin silver print, 101.6 x 50.8 cm.

In her 1990 How Mexican is Mexican series, Aguilar contributed a selfportrait, titled simply Part 3C, which features the artist stone-faced and bordered by lotería cards, with the accompanying caption reading: “NO longer the questioning / instead Room for forgiveness and / the belief in possibilities. / I am comfortable with who I have / become. This I never thought / would happen.” Her 1993 series Don’t Tell Her Art Can’t Hurt offers further insight into the mediation of her multiple marginalizations. Part B of the four-part series (individually identified as Part A-D) features Aguilar staring at the viewer, wearing a T-shirt bearing words from the series title, now partially obscured as she presses a gun to her face with her right hand. The text below challenges: “You learn you’re not the one they want, talking about prid [sic]. It’s the others who know about who we are. It’s the others who want to teach us who we are.” Part C features a headshot of the now-shirtless photographer, returning her gaze to the camera as she gently inserts the gun between her parted lips, seeming to rest it against her tongue. The accompanying text reads: “If you’re a person of color and take pride in yourself and your culture, and you use your art to give a voice, to show the positive, how do the bridges get built if the doors are closed to your voice and your vision?”

Aguilar’s status as a person of colour cannot be separated from her status as a working-class woman, a fat person, a queer or disabled person; these categories are always underlying and operating in tandem with her racialization—particularly when poor people of colour are the largest demographic of fat people in the US. Thus, Aguilar’s insistence on her comfort with herself must necessarily extend to her fatness, even if later statements might contradict this; marginal subjects inevitably possess ambivalent and fluid relationships to our oppressed embodiments. There is a tension between these two images, as there is with Aguilar’s later statements about body size: while she finally claims a comfort in her self—her total self—she also recognizes the fabricated barriers, stigmas and struggles externally produced against her. These are nuances, contradictions and possibilities frequently overlooked.

Aguilar’s work teaches us to fiercely pursue the pleasure in being on the margins. She offers models of pleasurable resistance to and subversion of systems of oppression—specifically, fatphobia. By speaking back through art, Aguilar’s work can and needs to be considered in the context of fatpositive activism. Because thinness is a value of institutional whiteness, fatphobia becomes a technology of racism when bodies of colour do not live up to this standard—and this is part of the explicit racism that Aguilar responds to in so much of her work. When she claims comfort with herself, this comfort is including her racialization, her body size, her sexuality; when she claims dissatisfaction, it is dissatisfaction produced by racism, fatphobia, homophobia, racialized misogyny, classism and more. Aguilar dedicated her career to combatting co-constitutive stigmas and oppressions of racism, homophobia, fatphobia, misogyny and ableism, on behalf of the soft, round bodies that sustained, guided and protected our ancestors for so long. She did this through demonstrating the joy and pleasure that can and does exist within this embodiment, alongside the struggle, the pain and the heartbreak.

Laura Aguilar, Nature Self-Portrait #5, 1996. Gelatin silver print,

40.6 x 50.8 cm. All images © Laura Aguilar Estate.

Laura Aguilar, Nature Self-Portrait #5, 1996. Gelatin silver print,

40.6 x 50.8 cm. All images © Laura Aguilar Estate.