The opening night of the 2019 MOMENTA Biennale de l’image in Montreal, in front of a packed audience at Galerie de L’UQAM, artist and author Maryse Larivière held up a small, hand-held stereo to the microphone so everyone could hear her recording of the viral 2005 post-Katrina interview in which Celine Dion defends the city’s looters: “Let them touch those things!”

Larivière then read from her poem “Un petit quelque chose,” from the MOMENTA catalogue: “Recognizing the ambiguity of the fate of human production, she knows very well that creating, manufacturing, reproducing, buying, stealing, possessing, appropriating, taking, organizing, processing, accumulating, throwing away, abandoning, recycling, managing, transforming are but variations on the self-same thing: the morbid spectre of hoarding.”

“Things” make up our lives—plants, animals and stuff stacked up and tucked away in our homes, our offices, our yards, steadily crowding our lived environments. We are preoccupied with acquiring them, with altering them and then with getting rid of them, and just as we are getting the hang of this management, new technologies find ways to fold a variety of “things” right into our bodies. In collaboration with executive director Audrey Genois and executive and curatorial assistant Maude Johnson, MOMENTA curator María Will Londoño has brought together 39 artists at artist-run centres, university galleries and museums across the city of Montreal whose work relates to this year’s theme: “the life of things.”

Momenta curator María Will Lonodoño has brought together 39 artists in solo and group shows at artist-run centres, university galleries and museums across the city of Montreal.

The biennial is divided into four overlapping thematic chapters, each of which “offer[s] different ways of imagining the relationships between human beings and objects”: (1) cultural objects and material culture (2) thingified beings or humanized objects (3) the absurd as counter-narrative of the object, and (4) still life in an age of environmental crisis. In solo and group shows, artists of all kinds have found ways to circle around this question of things.

This year is the 30th anniversary of MOMENTA, which was previously known as le Mois de la photo à Montréal. Though the medium was invented nearly two centuries ago, photography started to be taken seriously as “fine art” only in the late 1970s, not long before MOMENTA was founded as an international photography biennial in 1989. Lonodoño is “very interested in breaking the boundaries of photography” and has taken an expansive curatorial approach to this anniversary edition. For this reason, many of the works in the biennial go beyond the boundaries of two-dimensional photography, and include video, sculpture and installation.

Bridget Moser, Every Room is a Waiting Room Part 1, 2017 and Elisabeth Belliveau, Still Life with Fallen Fruit (after A Breath of Life, Clarice Lispector), 2017-19. Installation view, VOX, centre de l’image contemporaine, Montréal, 2019. © MOMENTA | Biennale de l’image and VOX, centre de l’image contemporaine.

Photo: Jean-Michael Seminaro.

Bridget Moser, Every Room is a Waiting Room Part 1, 2017 and Elisabeth Belliveau, Still Life with Fallen Fruit (after A Breath of Life, Clarice Lispector), 2017-19. Installation view, VOX, centre de l’image contemporaine, Montréal, 2019. © MOMENTA | Biennale de l’image and VOX, centre de l’image contemporaine.

Photo: Jean-Michael Seminaro.

At Galerie de L’UQAM, artists address the stereotypes reinforcing rigid gender binaries and oversimplified perceptions of cultural identity. Victoria Sin performs different poses of femininity and seduction in the multimedia installation Narrative Reflections on Looking (2016–17). In their video Triangle Trade (2017) Jérôme Havre, Cauleen Smith and Camille Turner use puppets, land and waterscapes to explore ideas of diaspora. Jeneen Frei Njootli’s Being Skidoo (2017) presents a crisp, vibrant series of tightly framed shots of life in the North. The late Laura Aguilar’s classic self-portrait series Grounded (2006–7) shows the Latinx artist nude in the desert in various poses that meld her with the landscape.

Several photo series use masks as objects of fantasy and defamiliarization. In Fortia (2017), the Angolan photographer Keyezua presents a woman wearing a striking red skirt and masks on a desert rockscape. Gauri Gill’s Acts of Appearance (2015–ongoing) photography series consists of performative montages of people wearing oversized animal masks in Jawhar, India. Exclusively in the catalogue is Road Signs (2012), a series of staged photographs by Kapwai Kiwanga of small roadside businesses in Tanzania with the recurring intervention of stretched-out bed sheets to obscure the sellers and frame what is being sold.

Gauri Gill, Untitled #27, from the Acts of Appearance series, 2015 – ongoing. archival pigment print. © Gauri Gill.

Taus Makhacheva, Tightrope, 2015. Video still (detail). Courtesy of Dagestan Museum of Fine Arts named after P.S. Gamzatova (Makhatchkala) and Cosmoscow Artists’ Patrons Programme (Moscow). © Taus Makhacheva.

Keyezua, Fortia 7, from the Fortia series, 2017, digital print. © Keyezua.

Laura Aguilar, Grounded # 111, from the Grounded series, 2006. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the estate of Laura Aguilar. ©The estate of Laura Aguilar.

At VOX, in the oddball, pastel-coloured choreography of Every Room is a Waiting Room Part 1 (2017), Bridget Moser treats certain things like other things and comically reanimates them with new life. Juan Ortiz-Apuy compiles montages of increasingly bizarre YouTube unboxing videos in The Garden of Earthly Delights (2017) and pairs them with still life–style installations of consumer objects. In Taus Makhacheva’s video Tightrope (2015) a man walks a tightrope to carry canvases between two mountaintops.

The same exhibition at VOX opens with Peter Fischli and David Weiss’s 1987 video Der Lauf Der Dinge (The Way Things Go). Londoño says this canonical 30-minute video, in which a series of objects propel others into motion in an series of events, was one of her starting points for organizing the show. The Rube Goldberg–like sequence is in line with the ways in which all of the works assembled fit together.

Alinka Echeverría, Precession of the Feminine series, 2015. Exhibition view, Montréal Museum of Fine Arts, 2019. © MOMENTA | Biennale de l’image and Montréal Museum of Fine Arts.

Photo: Jean-Michael Seminaro.

Alinka Echeverría, Precession of the Feminine series, 2015. Exhibition view, Montréal Museum of Fine Arts, 2019. © MOMENTA | Biennale de l’image and Montréal Museum of Fine Arts.

Photo: Jean-Michael Seminaro.

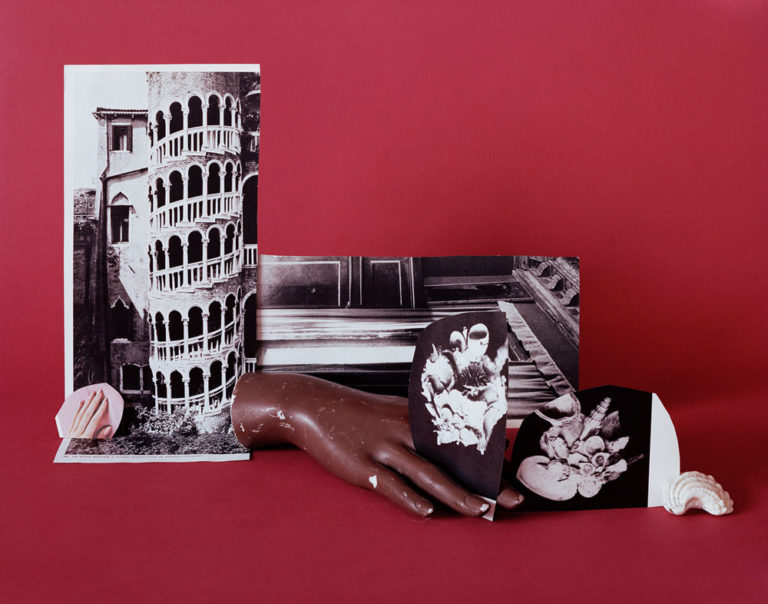

Celia Perrin Sidarous, Xenophoridae, 2019. Photograph, inkjet print. Courtesy of Parisian Laundry (Montréal). © Celia Perrin Sidarous.

Celia Perrin Sidarous, Xenophoridae, 2019. Photograph, inkjet print. Courtesy of Parisian Laundry (Montréal). © Celia Perrin Sidarous.

Londoño also asks artists to reimagine the genre “still life,” which is a trope of Western art history, and also the space in which, “historically, objects have been portraits.” In still life, artists are “putting together artificial objects and nature to show the passage of time,” Londoño explains, and for her, thinking about photography and the life of things, a new approach to still life was “a way to signify the crisis of the environment—how we affect things by the way we relate to objects we’re surrounded by.” Artists like Raphaëlle de Groot, Elisabeth Belliveau, Celia Perrin Sidarous and Hannah Doerksen present new works in the biennial in keeping with Londoño’s conception of the still life as relational.

Just as objects define our relationship to time and identity, they also help us create new worlds. This process, Londoño suggests, can be a political one: “I think this present world is making us more and more isolated. And social relations sometimes are so complicated by political tensions that I just think sometimes people prefer to live with objects.” Speaking of Hannah Doerkson’s solo exhibition “MAKING A RELIGION OUT OF LONELINESS,” she says: “I became very touched by her process because it’s not only about creation—it’s about her way of living. She lives surrounded by objects and she becomes attached to them in a psychological way…It’s all about solitude and it’s about creating a temple for one’s loneliness.”

My favourite piece was the The Drift (2017), by UK filmmaker Maeve Brennan, who spent three years filming in Lebanon. In documentary style, the video follows a conservator in archeology, a mechanic and a the gatekeeper to the Roman temples of Niha as they share their passions for protecting, excavating and making things from the past. The story is visually slow and pensive, with characters revealing themselves as it unfolds, which in turn reveals an impression of the greater social and historical context of the region.

The strength of this biennial is in the grouping of works old and new, and not in the introduction of new works.

Since its release in 2017, The Drift has been extensively reviewed and presented. Unlike most biennials, much of the work in MOMENTA is not new, and has previously been shown elsewhere, both in Canada and abroad. Many of the larger solo shows have been staged elsewhere, are ongoing or have been adapted for this context. Francis Alÿs’s solo presentation at the Museé d’art contemporain de Montréal, for example, showed an older ongoing series of videos of children playing games from all over the world (“Children’s Games,” 1999–ongoing). Still, the show worked extremely well in the context of the biennial. A rock, a stick and a ball can prove to be universal tools of imagination when used by children in different contexts.

In each of the biennial’s larger, thematic exhibitions, older works by artists like Ana Mendieta, Laura Aguilar and Peter Fischli and David Weiss can be found alongside more recent and newly commissioned works. Several artists are given an opportunity to expand their practices in solo and duo shows. The strength of this biennial is in the grouping of works old and new, and not in the introduction of new works. “I think it’s attractive enough for non-experts just to really get an experience off of ‘the life of the things,’” Londoño says. Though art-world insiders may have already seen versions of the presented works in exhibitions in other cities, Montreal audiences will be shown a cohesive and engaging biennial.

I came away from this year’s MOMENTA delighted by the intricate and imaginative works I saw, as well as self-conscious of the place of things in my own life. Larivière, thankfully, finds a way to articulate what causes my malaise: “For this distinction between art and trash is what secretly wards off a true encounter with the world. To abolish this symbolic boundary is to hear the inexpressible musicality of the world. So she’ll go slowly.” Like the character in Larivière’s poem, I too will go slowly.

The original version of this review was titled with text that miscontextualized the work of Maryse Larivière. We regret this error and have changed the title accordingly.