In advance of the inaugural Toronto Biennial this fall, Canadian Art is publishing a weekly series of behind-the-scenes features from artists, curators and participants in which they discuss the research and processes that inform their practices.

Tanya Busse: One of the threads we’ve been working with since we began collaborating in 2013 is the relationship between radical geology, contested landscapes and the body. Our first public artwork together was Hollow Earth, a large three-channel vertical video installation. It’s a visual meditation around resource sites within the circumpolar areas, particularly active mines in Northern Norway, Sweden and Russia.

Emilija Škarnulytė: We were both doing our master’s degrees at the Art Academy in Tromsø, located above the Arctic Circle, and we were surprised with the invisible and hidden politics and economics of mining in Northern Norway. For instance, in Spitsbergen there is a mine almost as big as the city of Oslo, but it is hidden in the mountains. We were interested in these invisible landscapes, and the heavily perforated landscape. So much seismic research and prospecting is being done in the Arctic, and it left a big impact on us—imagining how the fjords were going to look in the future.

TB: In general, New Mineral Collective is a collaborative platform that looks at the contemporary landscape and tries to understand the extent of human interaction with the Earth’s surface. Along with a group of international members, we primarily focus on geo-traumas, radical geology and the carving of new spatial geographies due to extractive industries. We integrate many approaches to land use and attempt to emphasize multiple points of view regarding the utilization of terrestrial and geographic resources. This comes out in our performances, videos, sculptures and printed matter.

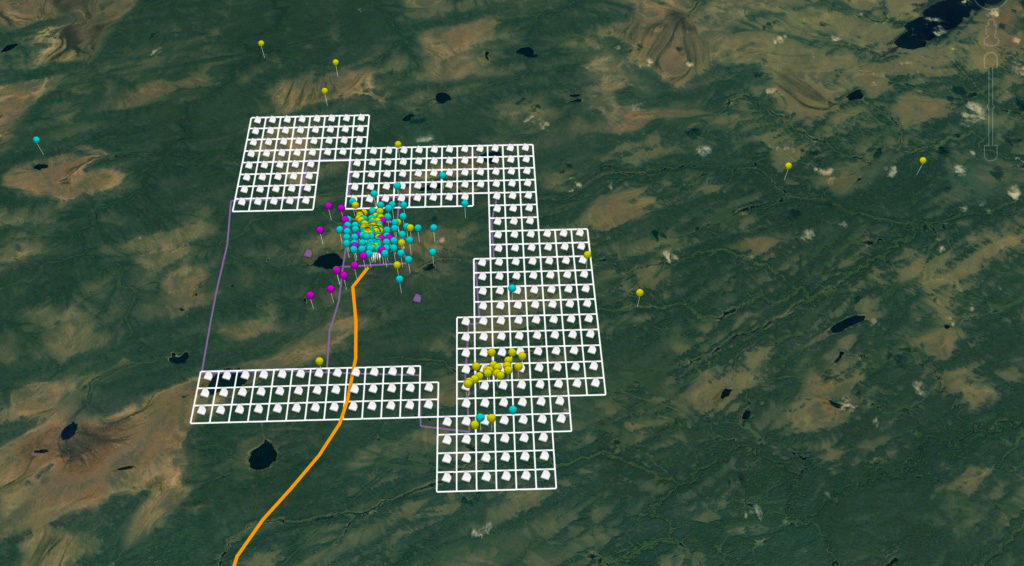

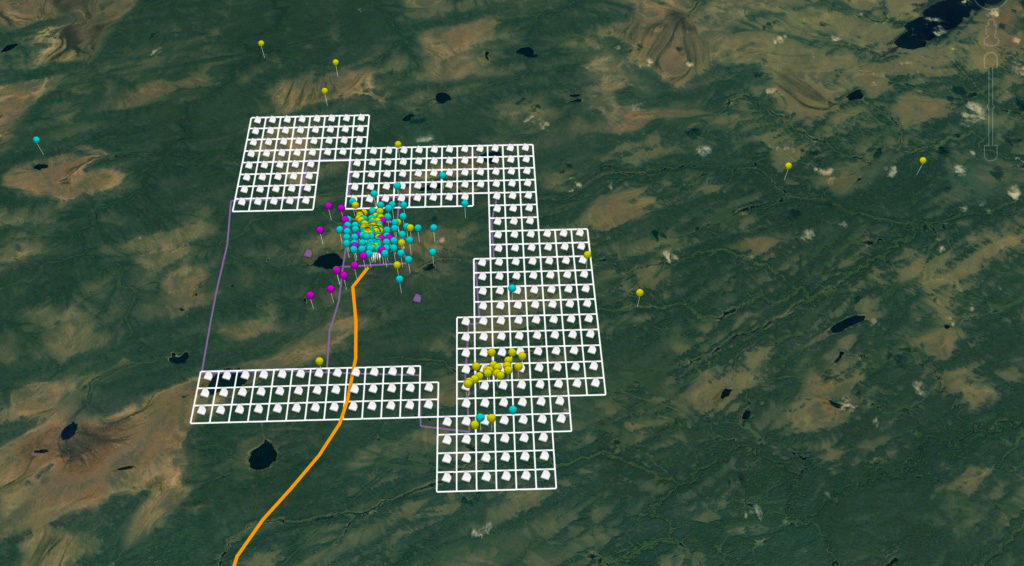

ES: The departure point for the Toronto Biennial has been the waterfront, which has been shaped by settler, slave and immigrant narratives from the Toronto Purchase up until now, and by much earlier and continuing Indigenous narratives. We are interested in the boundaries and borders that make up the territorial grid system of Canada. We began with the process of acquiring mineral licences, or rather prospecting licences, for Ontario. To do so, we had to pass the Mining Act Awareness Program, and go through different administrative processes, to familiarize ourselves with the legalities. For the Ontario claims applications, we used a topographical map (from the Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines) and Google Earth—it’s surprisingly very accessible, prospectors can be anywhere in the world, staking claims online. The whole process of applying and acquiring is, at its roots, very colonial. It’s a reminder of how mapping has been, and still is, a strategic tool of British (Crown) expansionism. These maps aid in both building and preserving power. There are specific numbers of each of the stakes you claim, and once claimed it goes through different offices—through different, invisible layers of procedure.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists

TB: Over the years we’ve had various exchanges with the Norwegian architect Kjerstin Uhre, who wrote the introduction to our publication Hollow Earth. In general we’ve been very inspired by her practice. I think the feeling has been mutual; she’s developed the term in relation to our work. The formal definition she’s given is: “Counter prospecting is introduced as an experimental and interpretive praxis-based method that operates on two intersecting planes: It resists dominant and already given prospects, while on a plane of anticipation it reaches beyond these in a prospective exchange towards possible alternative futures.”

To prospect means to search for mineral deposits, to inspect and to seek. When envisioning prospecting, we were specifically thinking about mining, and what you do when you’re going to prospect land—that is, to lay claims, stakes, take soil samples, collect data to see if there’s anything profitable. We’re very interested in exploring counternarratives to that, or [exploring] other things we could prospect that may not be capitalistic symbols.

ES: That’s where our counter-prospecting idea came from: to insert some alternative forces, energies, values, whatever you want to call them, into the world. It’s an idealistic approach. Counter prospecting is opening up these possibilities of what could be different. It’s a method we use and it’s one of the driving forces in our performances, videos and sculptures. And it is also a very present theme in our two new works for the Biennial.

TB: The whole process has really made us reflect (critically) over what it actually means to stake claim to plots of land. After seeing the cells on these topographical, digital mapping systems, we started discussing what would happen if they were claimed but just left passive, as opposed to continuing the cycle of extraction. To treat what is there (the scars on the land) rather than continuing to prospect. That would be the ultimate act of counter prospecting. We are inspired by people like Peter von Tiesenhausen, who in 1996 copyrighted his land as an artwork, which prevented a large oil pipeline deal from going through in northern Alberta, and climate activist Timothy DeChristopher, who in 2008 stopped the selling of 116 parcels of public land in Utah’s red rock country through an act of resistance at a Bureau of Land Management oil and gas lease auction. With our work, we survey areas, stake claims and hold licenses meant to give permission to prospect different plots of land. Imagine if these plots of land were left passive? Imagine staking claims to resist big business from moving in? There’s something really exciting and hopeful there.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists.

ES: Another act of counter prospecting we offer are “geo-therapies.” Our approach usually includes researching various locations and sites that have ailments, followed by prescribing treatments to heal their scars, wounds and geo-traumas. The geo-therapies we offer are connected to acupuncture, hydrotherapy, and the massaging of borders. For example, the acupuncture we do is for contested sites in the landscape where there are blockages of energies: environmental, political or socioeconomic pressure points. We have a New Mineral Collective toolbox that we use to treat both the body and the land.

TB: For the Biennial, we’re making two commissioned works: a film and a set of new sculptures, both titled Pleasure Prospects. The latter are geo-trauma healing tools. They’re about returning what has been taken from the earth, to question the idea of value and what is valuable. Our sculptures, located at the Small Arms Inspection Building, are columns/casts of various prospecting boreholes. Let’s say producing one gold ring results in 20 tons of slag [a byproduct of smelting]. So we’re using slag from regions around Ontario, and mixing the slag with local minerals such as copper, silver, aluminum, zinc, steel and gold, to create tools by adding value to the waste. It’s about replacing what has been already taken out of the earth, or making it whole again, in a way. Each tool is dedicated to a specific borehole that has been prospected already, and which has left a scar.

ES: These prospecting boreholes, the geologic samples, are quite easy to do once you have the prospecting licence. The first steps have been quite revealing. It was very easy for us—meaning it’s also easy for international corporations—to stake a claim online and get a licence for Ontario. Part of the work is about looking critically at how intricately connected and entangled Toronto, and Canada, is with the shady realm of the global extractive industry: something like 75 per cent of mining companies in the world are headquartered in Canada, with most headquartered in Toronto. It’s a resource capital and a major financial operating platform for the world’s mining industry. Flows of capital run throughout the TSX [Toronto Stock Exchange]. It’s really at odds with our image of Canada. Canada isn’t innocent when it comes to implementing strategies of colonization, neither abroad nor at home. We’re serving the speculators and exploiters of resources.

TB: This brings us to our other work in the Biennial, Pleasure Prospects, a new video work with three chapters. The first chapter is based on the digital screen and NMC’s process of acquiring mining claims and surfing through Ontario’s topographical landscapes and cells. The second chapter takes place at PDAC: The World’s Premier Mineral Exploration and Mining Convention, which happens in Toronto every year. It’s one of the largest in the world. Most of the world’s prospecting and mining companies have booths there, presenting their newest technology and services, sometimes with hilarious booth slogans, like “Your Hole is Our Goal” and “Penetration Is Our Destination.” It is a very male-dominant type of place. We hope to inject a different kind of energy. We’ve been shooting the third chapter at Ontario Place, and thinking of it as a counter-headquarters. NMC is prospecting for things with different values, and providing geo-trauma therapies there: hydro-drill therapy with synchronized swimmers, acupuncture-based landscapes, topographical points where actual drill holes have been made, and facials—procedures that mine through the body.

ES: Ontario Place is very special in terms of its aesthetic. We were very attracted to it because of the architecture—it’s retro-futuristic and has this timelessness where you don’t quite know if it’s in the past or the future or some kind of alternative dimension altogether. Everyone seems to have a personal connection with Ontario Place, but since neither of us did previously, we saw it through a different lens. It relates to this idea of alternative futures.

TB: Filming at Ontario Place, we were really focusing on Toronto as a global mining capital, a corporate capital and the site of the TSX. After the hectic PDAC 2019 convention, the partly abandoned Ontario Place offered a contrast—a different, suspended time. We injected it with female energy and transformed it into a powerful spa, so that is what it represents to us, in the film. It’s NMC headquarters.

ES: You know, each company has their own booth at the summit? Since we consider New Mineral Collective to be the largest and the least productive mining company in the world, we also needed an immersive, spacious headquarters.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists.

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists

Still from Pleasure Prospects, 2019. Single-channel 4k video. Courtesy of the artists