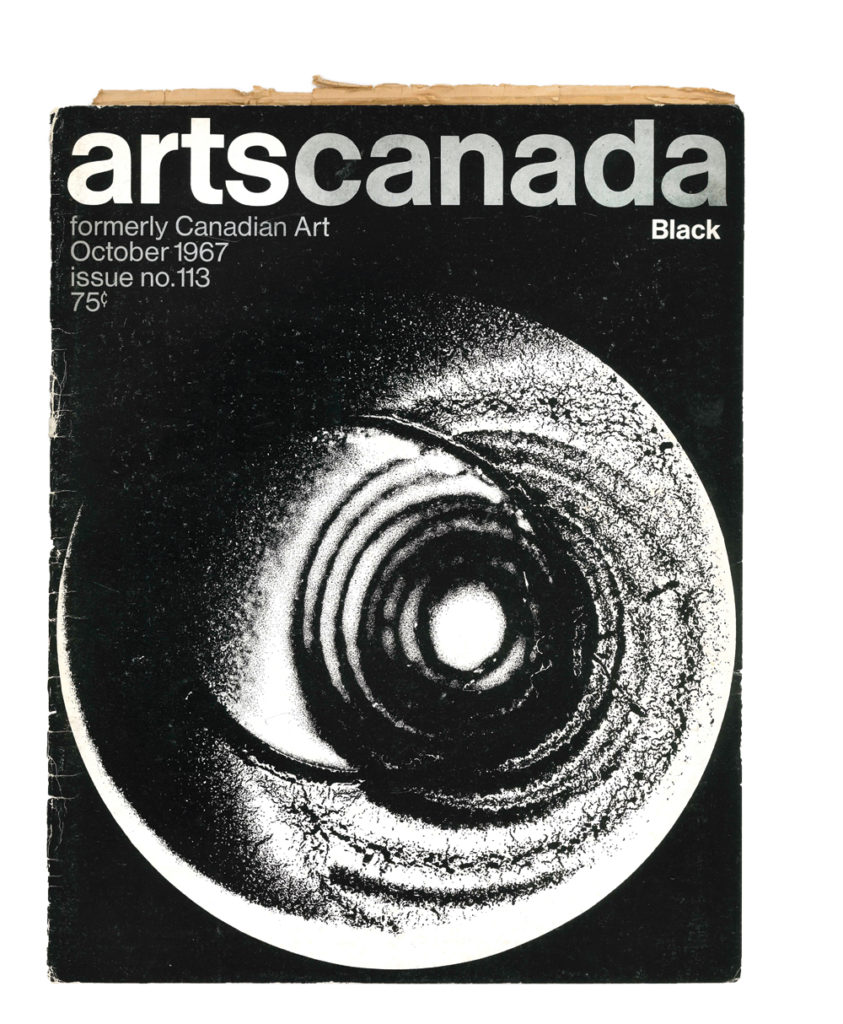

History can be misleading. Take for instance the October 1967 edition of artscanada—the “Black” issue. It was a loaded theme that promised, on the surface at least, to address the simmering unrest of the time head on. Only a few months earlier, violent race riots and protests had erupted in more than 150 cities across the United States—including in border cities such as Buffalo, Chicago and, most dramatically, Detroit—in what has become known as the “long, hot summer of 1967.”

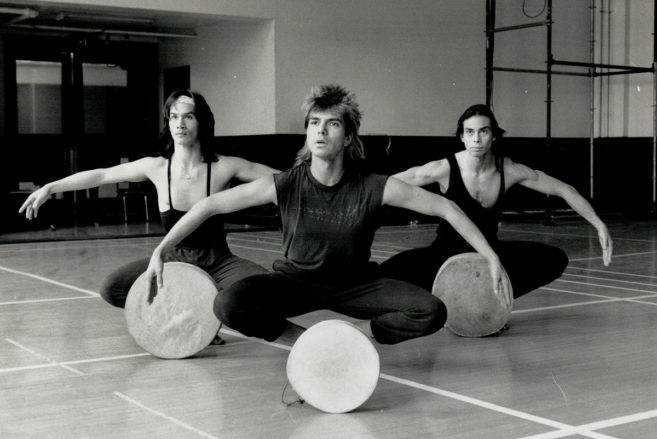

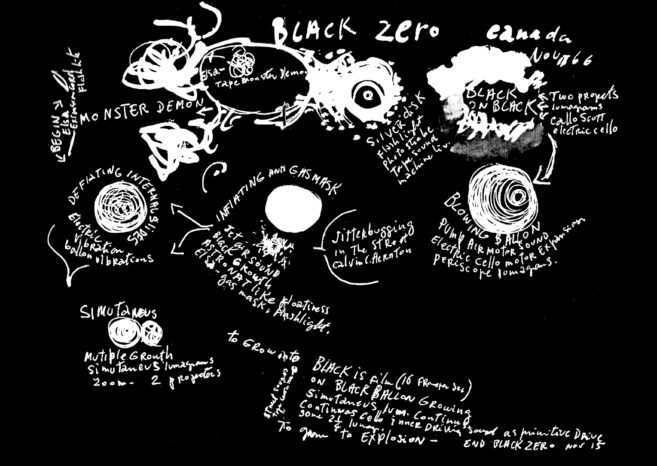

What we find in the artscanada pages, however, is something altogether different. The entire issue was dedicated to a transcribed conference call between Toronto and New York in August that year, where two artists, two musicians, an architect, a filmmaker and a sociologist—all men, all white, with the exception of Black American composer and poet Cecil Taylor—debated “black” as a quality of colour in paint; as perceptual blindness; as religious metaphor; as stasis, negation and nothingness. Aside from the inclusion of a Black Panther symbol to illustrate the text, the burning racial tensions of the time were mostly ignored.

Much has changed—and not changed—since the “Black” issue hit newsstands 50 years ago. (This particular issue came to our attention via Vancouver-based curator Denise Ryner, who is working on a research project that revisits the artscanada “Black” panel discussion.) In looking back, what becomes strikingly apparent, and important, is not the flawed history it contains, but the real stories that are glaringly absent from its pages.

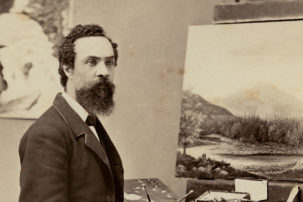

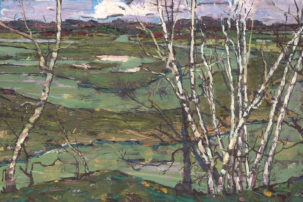

It is these missing narratives, the hidden, suppressed, overlooked and otherwise untold histories of Canadian art, that are the focus of this current issue. Think of it as our sesquicentennial-year counter-canon: read the little-known stories of pioneering artists Florence McGillivray and Grafton Tyler Brown; the under-recognized influence of Quebec critic René Payant and Indigenous artists René Highway, Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew, Archer Pechawis and Terry Haines; the winding tale of a 17th century painting stolen during the Second World War and returned to its rightful owners; the ongoing work of Black women curators across the country; and much more. These are the stories that matter now and set the record straight for histories yet to come.

Correction Notice: The version of this article that appeared in the Fall 2017 issue of Canadian Art erroneously suggested that the artist Archer Pechawis is deceased. Canadian Art deeply regrets the error and sincerely apologizes for any grief or harm that this has caused Mr. Pechawis and his family.

Cover of artscanada ’s October 1967 issue, from the Canadian Art archives.

Cover of artscanada ’s October 1967 issue, from the Canadian Art archives.