We’ve been talking about reconciliation for decades. What took the arts so long to catch up, and why are we still so far behind?

Almost three decades ago, there was a period of great change for Indigenous peoples. In 1990, the 78-day standoff over land rights at Oka in Quebec brought Indigenous sovereignty to the forefront of the national conversation. That same year, the rejection of the Meech Lake Accord over the exclusion of Indigenous rights fuelled debate over Canadian constitutional reform from coast to coast to coast. And the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, established in 1992, had begun examining the discrepancies between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. It was a time of promise and possibility for Indigenous peoples, and this was not lost on the art world.

At the time, Indigenous art was first being recognized as belonging to the Canadian art canon. Throughout the 1980s, more galleries and institutions began to feature Indigenous works as part of their Canadian collections. In 1986, the National Gallery of Canada bought Anishinaabe artist Carl Beam’s painting The North American Iceberg (1985), which was the first work made by an Indigenous artist to be bought for their contemporary collection. Just six years later, in 1992, the National Gallery toured “Land, Spirit, Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada,” the first North American survey exhibition of contemporary Indigenous art to be held at the gallery. Today, instances of works by Indigenous artists in major Canadian galleries and institutions are more common, but not yet widely seen.

Now, once again, the relationship between Canadians and Indigenous peoples is at the fore, in the arts and beyond. The Canadian government’s endorsement of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls have got many thinking that if enough effort and resources are applied, maybe a real difference could be made. But many are still skeptical.

After the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its 94 recommendations in late 2015, many Canadian arts institutions and funding agencies made reconciliation part of

their mandate, creating funds and jobs for Indigenous people. Those critical of reconciliations efforts in the arts see this as treating the symptoms and not the root causes that have kept more Indigenous people from entering and staying in the field.

Simply recognizing Indigenous art as Canadian art was a first step in reconciling the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian art world. Despite this, Indigenous stories and worldviews have trouble reaching art institutions. Some credit this to the fact that most curators, arts administrators, funders, policy makers and decision makers are non-Indigenous gatekeepers to the institutions.

“This has been talked about for 25 or 30 years,” says Ryan Rice, the Delaney Chair in Indigenous Visual Culture at OCAD University. “It goes back even further, where the ‘Indian Group of Seven’ were trying to get in the door in the 1970s. Now the door has opened slightly, and we have the tools behind us to get in. It’s just a matter of institutions letting us tell our stories, and giving us that agency to do so in their spaces.”

Duane Linklater, What then remains, 2016. Disassembled walls, powder-coated steel and steel screws. Dimensions variable. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Duane Linklater, What then remains, 2016. Disassembled walls, powder-coated steel and steel screws. Dimensions variable. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Working as a curator for more than two decades, Rice has seen interest in Indigenous art wax and wane, and he warns that the current national conversation around reconciliation could soon end. Rice points out that reconciliation between Indigenous peoples and Canadians has been going on for a very long time, and that it is only recently that it has come into national prominence. Since the attention and funds are fleeting, he says, it is rare that the work being done can get to the heart of the concept.

“It gets problematic when there’s funding attached to a project that’s supposed to correct something,” he explains. “When you open the doors to funding and allow anyone to apply, you can get some insignificant projects that deal with the issue superficially as a means to get the project done. We’ve seen this happen over and over with art institutions, where they know their purse strings are available and will pursue certain projects without any real foundational acknowledgement, follow up or any concrete evidence that they will continue these types of projects.” Rice says that Canadian art institutions need to do more than just hire Indigenous people. They need to have power and agency to carry out the projects that they see as important for Indigenous communities. He feels that many institutions often don’t know how to recognize Indigenous knowledge and labour.

“I get bombarded with a lot of consultations, [and requests to] speak for free or be on a round table. People don’t know how to approach you professionally,” Rice says with a weary chuckle. “It comes down to reciprocity: What is it that you’re offering somebody? Is it collaboration? Is it consultation? Whether its critical dialogue, collaboration or leading a project, consultation can’t be free anymore. There needs to be some sort of equity involved in these processes.”

Arts institutions can act right now, Rice believes, to hire more Indigenous people to fill key roles and collaborate within the existing structure. He says without Indigenous professionals in decision-making positions, a huge gap in perspective is missing from Canadian art.

“The institutions already with collections of Indigenous art should be the first ones to actively seek Indigenous people to work within those institutions,” say Rice. “We’re at a point where the education is there and the scholarship is there, and [academics] can take what we as Indigenous people provide and become specialists the same way the anthropologists and ethnographers became the specialists, and we were the informers. Today, we see how curators are positioning themselves more broadly, but they still should step aside and allow us to tell our stories.”

In 1991, Indigenous curator Lee-Ann Martin wrote a groundbreaking paper titled “The Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion: Contemporary Native Art and Public Art Museums in Canada,” in which she writes, “The exclusion of the arts of Native peoples implies that the artistic and cultural contributions to Canadian history by Canada’s First Nations [Inuit, and Métis] are non-existent.”

For Clayton Windatt, independent curator and executive director of the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective, little has changed. “When you read [what Martin wrote], it sounds like it was written today,” he says, with frustration. “It talks specifically about how there are no tangible resources for Indigenous curators or Indigenous organizations. There are a half-dozen Indigenous curators across the whole country that have permanent jobs. None of that has changed since 25 years ago.”

Even though progress has been slow in this regard, Windatt says that now is not the time to rush in with solutions to try and quickly solve reconciliation in the arts.

“Reconciliation is not going to be fast, and it’s not going to be cheap. It’s a big thing. We’re all going to have to live together forever,” says Windatt. “The real challenge right now, with all these reconciliation conversations, is that government is rushing to the end. It feels like they’re saying, ‘If we celebrate now, if we give a lot of money now, then things will get better.’ It’s called truth and reconciliation—and we still haven’t really finished the truth part yet.”

Right now, on the year of Canada’s sesquicentennial, a lot of money and resources in the arts are being promised to Indigenous peoples, from institutions such as the National Gallery, various provincial art councils, the Canada Council for the Arts and more under the banner of reconciliation. Windatt says that there is still a major disconnect.While he is happy for his colleagues getting the support and funding they need, he thinks there is a fundamental misunderstanding that lingers regarding the value of Indigenous knowledge and experience.

It is no longer acceptable to expect free Indigenous labour because its considered “helping” to further understanding, says Windatt. “You become a cultural mediator, in a way,” Windatt says, but points out that,“If this was a legal, human-resource or corporate mediation, you’d be paid anywhere from $200 to $1,000 an hour for this work.” He corroborates that he and his colleagues regularly get requests to work for free.

Sonny Assu, Home Coming, 2014. Archival pigment print of digital intervention on Paul Kane’s Scene near Walla Walla, 1848–52. 57.3 x 81.9 cm. Courtesy Equinox Gallery/Art Mûr.

Sonny Assu, Home Coming, 2014. Archival pigment print of digital intervention on Paul Kane’s Scene near Walla Walla, 1848–52. 57.3 x 81.9 cm. Courtesy Equinox Gallery/Art Mûr.

The term reconciliation itself does not sit well with many Indigenous people. Artist Duane Linklater, a member of the Moose Cree First Nation, says that reconciliation is on the terms of the state, not the terms of Indigenous peoples. “I ask if the narrative or the ideas that are within reconciliation are Indigenous at all,” he says. “It somehow suggests that Canada and the state have completed or finished or stopped their colonization of Indigenous people and that it’s time for them to make up for that. And of course, they haven’t. There are still so many different forms of colonization that are functioning today and probably still tomorrow.” Linklater points out the hypocrisy of apologizing for residential schools or the Sixties Scoop while children are currently being removed from their families and communities and put into foster care at nearly twice the rates than those recorded at the height of residential schools—despite repeated demands to address this problem from Indigenous leaders and child advocates such as Cindy Blackstock. While art institutions are not directly involved in this process, Linklater says that by attaching reconciliation to their mandates, institutions become part of the mechanism the state uses to atone for its sins.

“It’s important to say that these institutions are publicly funded, that in some way they receive public funds,” Linklater continues. “They should be held accountable in relation to the conversation that we’re having in regards to Indigenous representation within their structures: Indigenous curators, Indigenous people in the archives, Indigenous people working within their collections—and contemporary art collections specifically. If the institution acquires art, and has the budget to annually acquire contemporary art, I would propose that a certain percentage of that acquisition budget be for Indigenous contemporary art.”

This does not mean that Linklater is opposed to Indigenous artists accepting funding for reconciliation projects. He thinks that is a good start, but not one that provides a long-term solution. “An Indigenous exhibition shouldn’t just happen every once in a while, when museums and other art centres see an opportunity to check a box,” he says.

And Indigenous art doesn’t just exist in arts institutions and galleries. There is a thriving Indigenous art market in Canada, operating mainly in major urban centres such as Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver.

Each year, Montreal’s Old Port sees more than six-million tourists from around the world. While there are still tourist shops selling knock-off Inuit carvings and dreamcatchers made in China, there is also the Ashukan Cultural Space, which sells work sourced directly from Indigenous artists and craft producers. Nadine St-Louis started Ashukan as an economic incubator to bring works from Indigenous communities across Quebec to thriving tourist market in metropolises. Crafting is a way for Indigenous peoples to maintain and pass on traditional skills such as sewing, beading and carving. Selling their work is a way for them to participate in the economy using the skills and resources already at their disposal. However, because of distances, access to materials and transportation, among other reasons, it can prove challenging for many Indigenous artists to reach these larger markets. St-Louis sees Indigenous artists claiming this space in one of the country’s largest urban centres as an act of decolonization.

Even though her organization usually works outside the institutional art framework, St-Louis often hears calls for additional funding and support for Indigenous artists. She believes that increased Indigenous representation in the arts will help to expand Canadian society’s understanding of not just Indigenous peoples, but also of itself. She sees Indigenous artists and arts professionals as blazing a trail for generations to come.

“I think every piece that is created, whether a sculpture or a painting or a moccasin or some traditional beadwork, or anything that stems from the traditional artistic practice, embodies a history,” says St-Louis. “In being able to share those items, you’re making room for acknowledgement for showing and for sharing.” While St-Louis believes that Indigenous peoples are the only ones that will be able to bring Indigenous culture and art to prominence, she says there is still support needed from government.

Quebec is the only province whose arts council does not have specific arts funding for Indigenous artists and arts organizations. But that’s all about to change, says Anne Marie Jean, CEO of the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec (CALQ). On February 7, 2017, CALQ issued a press release saying that the arts council will target Indigenous artists and that the jury will be made up of Indigenous people until a new Indigenous-specific program can be developed.

“We looked at our numbers, and it is obvious that we do not reach as many Indigenous artists as we should,” says Jean. “We know there are not enough artists submitting projects outside of Montreal, Quebec City or even Trois-Rivières. The further you go from the larger centres, the fewer Indigenous artists we reach, unless we have an agreement with a particular Indigenous group. But that can be long and complicated because we have to go through the Quebec government.”

Jean says that after consultation with Indigenous leaders and artists, it was decided that CALQ would develop funding programs specifically for Indigenous artists. Groups can still negotiate special deals with the arts council, but the goal is to make it easier for artists to apply.

“We feel that we need to carve out a new program closer to the needs of Indigenous artists,” explains Jean. “We are creating outreach programs to make sure that we talk to people from different regions and explain that we want to adapt to their needs and not ask them to adapt to us.” While there are currently no Indigenous employees working internally at CALQ, Jean says that will change later in 2017 when they plan to hire an Indigenous person to run their new Indigenous arts program. While the details of how this will unfold are not determined yet, she says the will is there.

Montreal-based Nunavimmiut filmmaker and curator Isabella-Rose Weetalatuk applauds CALQ for identifying these problems and acting to change, but she is wary of separating Indigenous contemporary artists from mainstream Canadian contemporary art. She is happy that CALQ will be hiring a special jury composed of Indigenous peoples to evaluate Indigenous artists, but she says there is still more to be done.

“There should also be Indigenous people on the jury for not just the Indigenous projects, but all projects,” she says, “and vice versa, too. I think it’s important that we’re all looking at each other’s work and seeing and learning from each other. What I would be afraid of is separating the art world too much. There has to be a place where we can all intermingle. Maybe we’re not there yet, but ultimately that should be the goal.”

Weetalatuk is working on her film 3000, and also curating an upcoming retrospective from Inuit media company Isuma. She sees parallels between the worlds of Indigenous film and contemporary art.

“It’s always good to have more Indigenous people in decision-making positions that understand the value of these works by having Indigenous perspectives,” she says. “I think the problem now is that the people who choose to give funding don’t understand just why these stories from Indigenous storytellers are important, or why they have value. [In order] to assign a fair value so that people can understand these stories, you need Indigenous people in those positions, at different levels.”

Weetalatuk welcomes continual funding for Indigenous artists, and believes it is needed to create an Indigenous art market, integrated into the mainstream, that has Indigenous people working at all levels. Sporadic funding discourages many from becoming full-time, lifelong artists and arts professionals, she says. Indigenous artists need an extended chance to develop professionally. Most important, says Weetalatuk, these groups and institutions will have to give up some of their power and space to Indigenous peoples.

Much has changed since Lee-Ann Martin first wrote her seminal paper on Indigenous inclusion in the arts 25 years ago. Works from great Indigenous artists such as Alex Janvier, Annie Pootoogook, Norval Morrisseau, Kenojuak Ashevak and Daphne Odjig hang in art institutions alongside prominent Canadian artists, helping to define Canadian identity. However, for some Indigenous arts professionals today, it might as well still be 1991.

But Indigenous curators like Windatt and Rice are optimistic. They say that they see education at the post-secondary level as a way forward to make sure that the story of Indigenous art is fully included in history of Canadian art. Not only will it create a better understanding of the Indigenous worldview, but it will also inspire generations of Indigenous artists and arts professionals to come.

Ossie Michelin is a freelance journalist from North West River, Labrador. Michelin worked for five years with the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, and has contributed to publications including Labrador Life Magazine, Newfoundland Quarterly, Inuit Art Quarterly, Atlantic Business Magazine and Ricochet Media.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of Canadian Art magazine. To get every issue delivered to you before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.

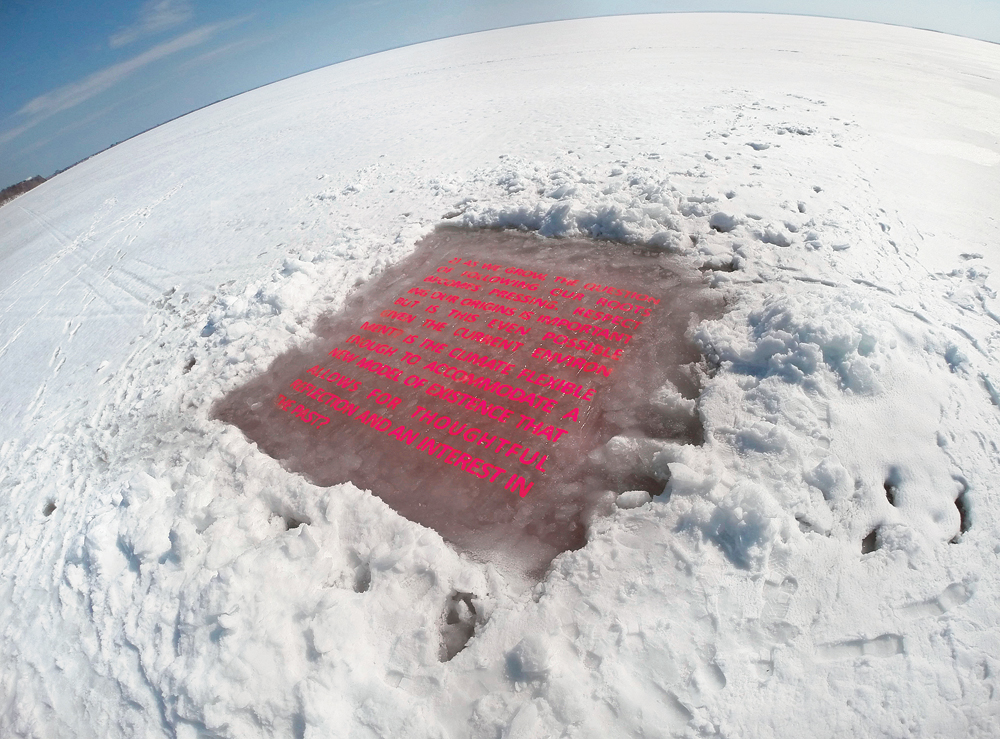

Installation view of Clayton Windatt and Fynn Leitch’s Installation number 2 (2014), unofficially in “Ohkwamingininiwug,” the Ice Follies biennial on Lake Nipissing

Installation view of Clayton Windatt and Fynn Leitch’s Installation number 2 (2014), unofficially in “Ohkwamingininiwug,” the Ice Follies biennial on Lake Nipissing

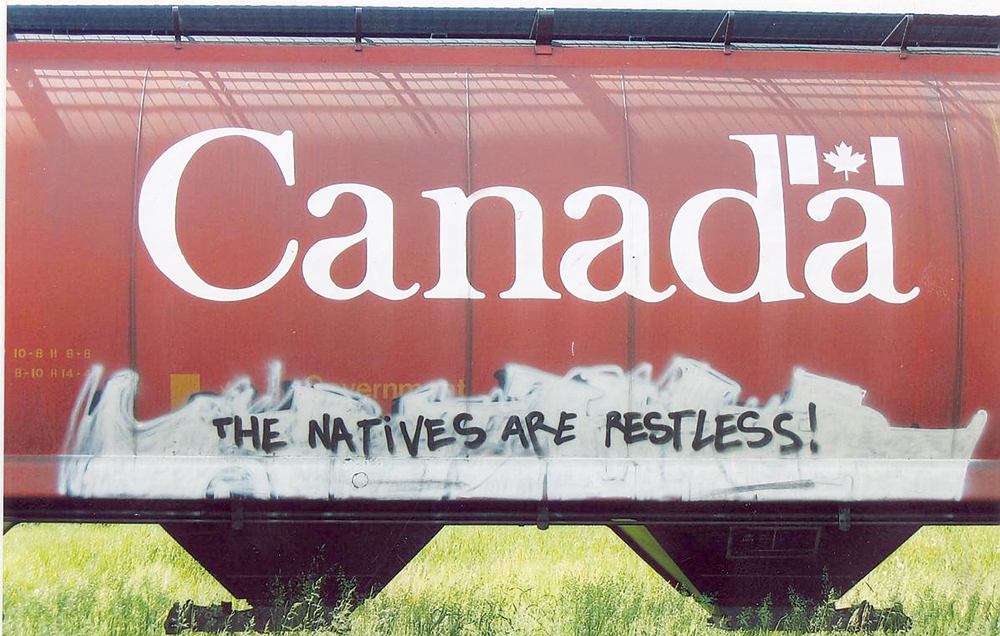

David Garneau, Restless, 2001. Photograph. Dimensions variable.

David Garneau, Restless, 2001. Photograph. Dimensions variable.