They say we all come from somewhere. Tau Lewis’s artwork comes from our shared histories, from those Black, southern, Caribbean, continental African and diasporic micro-histories, from those risks people took to come together on the corner, in the park, in the kitchen, on the porch and on back roads.

Lewis, who collects recycled materials, textiles and found objects that she then puts into her time-intensive sewing, carving and assemblage practices, is in essence a portraitist—of nonhumans, of non-citizens, of dolls, of the socially dead, of place and space, of bewilderment. Lewis emphasizes the physical at a time when press releases bow before the screen as if it were an altar, a time when the digital forgets its own materiality, forgets those sites where it stores its clouds, forgets the dumping grounds in Africa where our electronics go to die.

Artists without formal or institutional training, like Lewis, are often anointed as novelties, tasked with bringing the primitive to the highbrow art world (think of Jean-Michel Basquiat touted as a street savant). But Lewis’s understanding of being “self-taught” is not so much about the teacher as an individual, but rather as a collective. Part of her pedagogy is to seek out her artistic predecessors while they’re still alive, talk with them, hang with them, collaborate with them—to learn with and through them. Born in 1993, Lewis is a young artist paying homage to those so-called folk, outsider, self taught and other artists who make work under and against a host of names because the art world (a euphemism for a commercial world) desperately wants to pin them down, to capture them, but can’t.

Tau Lewis, Crystal Rock (detail), 2019. Repurposed leather, denim, plaster, acrylic paint, rope, office-chair wheels, snail shells, found metal, cotton batting, concrete, copper pipe, seashells, stones and hardware, 1.27 m x 76.2 cm x 109.2 cm. Courtesy Oakville Galleries. Photo: Laura Findlay.

Tau Lewis, Crystal Rock (detail), 2019. Repurposed leather, denim, plaster, acrylic paint, rope, office-chair wheels, snail shells, found metal, cotton batting, concrete, copper pipe, seashells, stones and hardware, 1.27 m x 76.2 cm x 109.2 cm. Courtesy Oakville Galleries. Photo: Laura Findlay.

Lewis’s origins are originary, by which I mean they aren’t fixed, and can’t be: her origins move. Recycling, a mode to which Lewis is wed, is a cycle, a renewal of what would otherwise be thrown away, left behind or forgotten.

More specifically, Lewis comes to us with people before her, such as Lonnie Holley and his tire sculptures or Dinah Young and her yard work or Thornton Dial and his steel monuments or Joe Minter and his African Village in America. Or the surrealists—Aimé Césaire, Suzanne Césaire, Léopold Sédar Senghor—who pushed poetic counter-narratives of the present. Or Noah Purifoy, who transformed trash into wonder-deserts in a mode that Amiri Baraka might call “Black Dada.” Or Betye Saar, who forms found objects into gun-toting mammy figures. Or Faith Ringgold’s representational quilts. Or sculptures by Huma Bhabha, Diamond Stingily, Georgia Dickie or Kevin Beasley. Or maybe even the cultivated “Doll Babies” brought to life by Martha Nelson Thomas, or the “feminine monsters” of Bonnie Lucas. Or what about Lauren Halsey, who builds whole funkadelic ecosystems inside and outside galleries, making us rethink what it means to be outside an art space even while physically in it?

Lewis grew up in the urban environment of Toronto (like me) with Jamaican parentage (also like me), and what could we, I mean she, possibly have in common with these old homies, by which I mean our dear elders, Holley, Young, Dial, Minter and others, from the deep South? Well, their work, our work, is made in plain sight but also in a kind of underground. Of all these artists, one stands out. In 2019, Lewis said that Lonnie Holley is “probably my favourite artist, one of my favourite people that exists in the world.” Holley is an artist and musician born in Jim Crow–era Birmingham, Alabama, who, through densely arranged sandstone, remnants and metaphors, addresses the outlandish nightmares of America. In 2014, he described his practice to the New York Times by way of a phrase popularized by Malcolm X: “by any means necessary…. We can make art where we have to.” There’s urgency in that statement, akin to how poet and scholar Fred Moten wrote on Alabamian multidisciplinary assemblage artist Thornton Dial: “I’m here to testify not only to Thornton Dial’s greatness but also to the fact that he didn’t come from nothing. Mr. Dial has something to say; nothing will come from nothing, speak again.”

Installation view of Tau Lewis’s (clockwise, from centre) Miracle of the deep sea, The Coral Reef Preservation Society and Devil Ray (all 2019) at the Yorkshire Sculpture International, 2019. Courtesy Hepworth Wakefield, West Yorkshire. Photo: Lewis Ronald.

Installation view of Tau Lewis’s (clockwise, from centre) Miracle of the deep sea, The Coral Reef Preservation Society and Devil Ray (all 2019) at the Yorkshire Sculpture International, 2019. Courtesy Hepworth Wakefield, West Yorkshire. Photo: Lewis Ronald.

Lewis’s origins are originary, by which I mean they aren’t fixed, and can’t be: her origins move. After all, recycling, a mode to which Lewis is wed, is a cycle, a renewal of what would otherwise be thrown away, left behind or forgotten. Together, Lewis and the artists who come before and alongside her build an improvisational repository for what cannot or will not be said, an intimate evidence of the “we” from which we came, evidence that there is a “we” to begin with, and that it starts with counter-hegemonic Black creative practice.

In Lewisian fashion, with and because of Lewis, I have here compiled a small chorus of Lewis’s actual and potential co-conspirators to show some of the many lineages her work follows. Through what Holley has called “furious curiosity and biological necessity,” these artists twist circumstance and constraint to make something other than what is. This incomplete list is something like what Tonika Sealy Thompson and Stefano Harney call, following historian Walter Rodney, groundations, that particularly Caribbean mode of rigorous study of shared roots. “In the Caribbean roots do not go just into the earth,” Sealy Thompson and Harney write. “They grow out of it, radiating outwards in waves and coming to our shores in waves, in what the Barbadian poet Edward Kamau Brathwaite calls tidalectics.” Lewis makes me wonder: How are roots made through processes of dispersion, scavenging, collecting and foraging?

As with Brathwaite, Lewis’s concern is also Afro-diasporic: those Black aquatic geographies (the ocean, the sea), the instability of water’s flow, the nowness of the Middle Passage: Her Soul of the sea (2019) erodes a species divide. In Water flooded out of my heart pocket (2019), shades of denim and leather make up the oceanic and give it flesh. In What in the water? (time capsule #3) (2018), water is personified, a body of plaster, cloth, acrylic paint, foam sealant and “secret objects.” And there is the large, hand-stitched tapestry The Coral Reef Preservation Society (2019), with its jagged edges, coral growths, seahorses and cephalopods. Quilting is a rich Afro-diasporic tradition, an art of the world historical. The word “tradition” does not quite cut it because quilting is tectonic: historically significant, large-scale, constructional, processual. Its title referencing a print that hung in Lewis’s family’s home and depicted the coral reefs, fish and other sea creatures of Negril, Jamaica, The Coral Reef Preservation Society was made, patch by patch, while Lewis was on the road. Her quilt practice moves as she moves, through travel in Canada, Jamaica, the United States and England, and between art shows and fairs. Fragments are resurrectional, catching something of every location, and so each contains unique sensuous memory, aesthetic possibility, trace, haptic history and ceremony. Each of Lewis’s materials—old clothes, found photographs, the artist’s personal earrings, curtains, blankets—has had some earlier use, some known and unknown, and carries an affective history, something that Lewis has referred to as a “charge.”

Tau Lewis, I heard a heartbeat down in the black hole (detail), 2019. Recycled leather and found metal, 2.4 x 2.3 m. Courtesy Oakville Galleries. Photo: Laura Findlay.

Tau Lewis, I heard a heartbeat down in the black hole (detail), 2019. Recycled leather and found metal, 2.4 x 2.3 m. Courtesy Oakville Galleries. Photo: Laura Findlay.

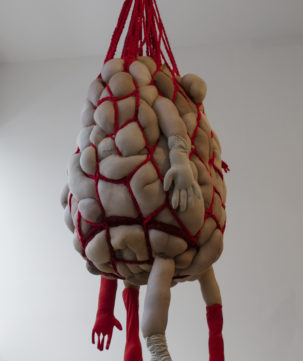

Whereas Lewis’s earlier work frequently drew on harder materials such as wood, scrap metal, cement, wire, plaster, stones, paint cans, chains and rebar, her latest work relaxes further into fabric. She has been making these soft sculptures with hand-sewn fabrics, furs, leather, polyester batting and jute for years—and they seem to have gotten softer. Her soft portraits from 2019—Spore (dangerous solar particles), Thumper (heartbeat of the sun), The Octonaut (I can be my own hands to hold), Miracle of the deep sea and others—double down on sewing, patchwork, quilting and stitching. By exposing the manifoldness of her portraits, she illuminates how objects are storied: thick with imagination, gesture, the unverifiable. Her figural sculptures, in their infinite supplementarity—seashells as toenails; leather as the skin on a lip; denim as cheekbones; bright buttons as ear-canal entryways; falling, cream-coloured yarn as eyelashes—almost occlude the deep and long labour her art requires.

Layers and rips and cuts and textures and tags and tears—these are the geographies of Blackness made visible by Lewis’s touch: shaping things and feeling things, reminding us that those historically considered things have feelings too.

Installation view of Tau Lewis’s (from centre, front) Seashell, What in the water? (time capsule #3) and Making it work to be

together while we can (all 2018). Courtesy Cooper Cole.

Installation view of Tau Lewis’s (from centre, front) Seashell, What in the water? (time capsule #3) and Making it work to be

together while we can (all 2018). Courtesy Cooper Cole.