Generously supported by RBC

What does it mean to care—a word that, as a verb, acts out a suggestion of affection, desire, provision and apprehension. But it also functions as a noun: the simple anticipation or attention brought to something with the general intent of bettering it. The word is also tied to the notion of concern and anxiety, which is perhaps why, in a culture with elevated levels of worry and mental dis-ease, care work is (not so suddenly) a hot topic. Wellness, too, for what is the idea of wellness other than care for and care of our vessels?

Curation is tied to care. No need to remind you the reader (but I will, just in case) that curation comes from the Latin cura (to care) and also points to the clergy, those vessels assigned to our collective spiritual care, if you chose to align your physical body (and your financial means) in their direction. Which brings us here, this assembly of persons, whose practices and projects are invested with ways of caring, either for themselves or for others. These various subjects (here used only as a noun) are keeping themselves well through a range of means, tending to needs both big and small, keeping safe that which requires safekeeping, acting when tangible gestures are necessary and refusing when that is the only way to stay well.

You may find yourself, reading through this list, making links with the ideas of mindfulness and other therapeutic practices that most concern the individual, but mostly there will be a focus on the theme of community and collective care. This manifests in a multitude of forms, from the physical to the more metaphysical, but the ways in which we take care of each other—how we share the affective burden—might be the vector through which we can bridge the seeming void between theory and praxis in the (art) world.

Andreja Dugandžic and Sonja Zlatanova’s performance for the 2017 VIVA! Kitchen. Courtesy Viva! Art Action/La Centrale. Photo: Manoushka Larouche.

Andreja Dugandžic and Sonja Zlatanova’s performance for the 2017 VIVA! Kitchen. Courtesy Viva! Art Action/La Centrale. Photo: Manoushka Larouche.

VIVA! Kitchen

The kitchen at the VIVA! Art Action festival began as a tool to feed the artists and the audience at the event’s first iteration in 2006. It was initially a working kitchen—mostly organized by one of the invited artists, SP 38—providing material for a “real” formal performance, but the kitchen quickly became the work itself. It is now defined as an artist-in-residence opportunity, and the meals themselves, as well as their creation and distribution, are the performances. No one who attends VIVA! will go hungry (all the normal concerns regarding diet and allergies are attended to), but more than just physical needs are met here. Michelle Lacombe, director of VIVA! since the 2011 edition, notes that the meals aren’t free but they are cheap. They are priced on a sliding scale from $7 to $10, which subsidizes the entrance-fee-free festival, but no one who needs a meal is turned away.

This year, Andreja Dugandžic and Sonja Zlatanova, two artists from Sarajevo and Montreal, respectively, cared for the kitchen. The latter has tended to the kitchen on two previous occasions, and this year the two focused on gendered cooking practices. They explain that they are “cooks and feeders. We give love through food; we hurt through it too.” Together they created a menu rooted in the Balkan spirit and the language of love, loss, abandonment and the feminized body. As they say, food is life. To consume is primal and to provide for is to care and nurture.

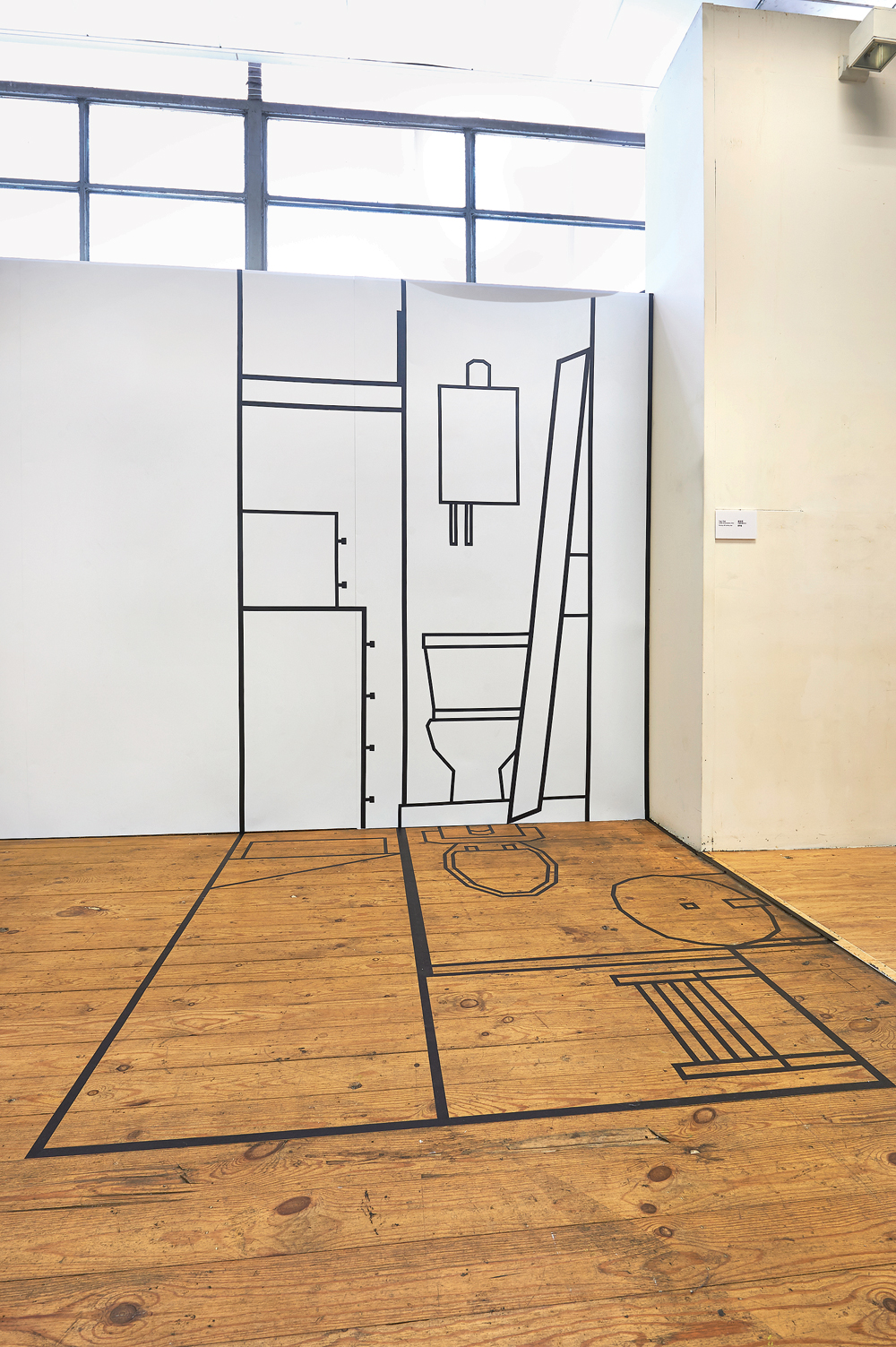

Tings Chak, Suitable Accomodation (detail), 2016. Masking tape. Dimensions variable. Photo: Eddie CY Lam.

Tings Chak, Suitable Accomodation (detail), 2016. Masking tape. Dimensions variable. Photo: Eddie CY Lam.

Tings Chak

Who provides care, who is deserving of and entitled to care, and who cares for the carers are all questions posed in works by Toronto artist Tings Chak. Ensuring that everyone has access to care and examining issues of spatial justice (who can be in a space) are core themes for Chak, who comes from an academic background in architecture.

In her 2016 installation Suitable Accommodation, which debuted at Central Oasis Gallery in Hong Kong’s financial district, Chak investigates the liminal space between public and private realms for migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong. Lacking personal space and fearing that they will be forced to perform unpaid labour on their day off, many such workers leave the homes they work and live in early on Sunday mornings. While most residents of Hong Kong consider grooming to be a private ritual, these domestic workers—numbering in the hundreds of thousands—congregate in public parks and plazas to paint each other’s nails, take naps, chat and, most importantly, organize themselves. By mapping these domestic workers’ private living spaces in 1:1-scale masking tape drawings, accompanied by testimonials on their living and working conditions, Chak reveals the pardoxes of “suitable accomodation” and how, under neoliberalism, caring and being cared for remains a precarious, if pervasive, negotiation of space and self.

Artivistic, World (War) Music International Incorporated Inc., 2015. Digital mockup.

Artivistic, World (War) Music International Incorporated Inc., 2015. Digital mockup.

Artivistic

Formed in 2004, Artivistic currently operates as a Montreal collective organized entirely by people of colour. Its current members include Faiz Abhuani, Nazik Dakkach, Sophie Le-Phat Ho, Kevin Yuen Kit Lo and Võ Thiên Viêt. As an arts organization, they have put on festivals, written zines and produced artworks, such as World (War) Music International Incorporated Inc. (WWMIIInc), a rumination on POC voices in a majority-white art scene.

The collective is currently in what they have dubbed their #postlife phase, having de-incorporated, de-institutionalized and closed their bank account. They had initially replicated traditional arts infrastructures to access certain types of art-world support, but when these supports were no longer serving their needs, and when the collective felt that they were being used in ways that drained instead of sustained them, they opted out, ending their engagement on that superficial level. Their activities have since refocused on friendship and mutual support. Collectively cooked meals and celebratory dinners are at the centre of their meetings. For Artivistic, food is intertwined with discussions about sharing, friendship, money, infrastructure, race and class. Members share responsibilities and costs based on means and ability. While still actively producing work, they are doing so less publicly. They are working on their own terms—turning care into a methodology, rather than an afterthought.

Jessica Karuhanga, through a brass channel, 2017. Performance. Photo: Manolo Lugo.

Jessica Karuhanga, through a brass channel, 2017. Performance. Photo: Manolo Lugo.

Jessica Karuhanga

Jessica Karuhanga tends to cultivate collaborators for her projects over several years, building the kind of trust that only comes with putting in the time to earn it. The Toronto artist works primarily in video and installation. Her practice deals heavily with gesture and choreography and speaks against our societal lust for the Black body as entertainment. Karuhanga empowers her collaborators with artistic agency, creating a shared space, a conversation, or, as she considers it, an undulation flowing between them. Her videos are about her experiences; they are meditations on the geopolitics of Blackness.

Works such as A Still Cling To Fading Blossoms (2014) challenge where and when the Black body exists in Canada, past and present, while also ruminating on the “incalculability of Black grief and mourning and where/how that can safely exist.” For an upcoming multi-channel video work prospectively titled being who you are there is no other, Karuhanga attempts to stealthily insert herself into an exclusionary cultural canon (including Sinead O’Connor, William Butler Yeats and the Trojan War). Her wider practice recognizes the absence of the Black, female body in the image of the Great White North. Karuhanga plays with the blues and gospel aesthetic to sneak into the Canadian landscape, so to speak, asserting her presence through building community.

Atelier Céladon, “A Glass House Should Hold No Terrors” at the Royal Victoria Hospital Pool, Montreal. August 2016. Photo: Oliver Lewis.

Atelier Céladon, “A Glass House Should Hold No Terrors” at the Royal Victoria Hospital Pool, Montreal. August 2016. Photo: Oliver Lewis.

Atelier Céladon

Atelier Céladon, founded in 2015, is comprised of Hera Chan, Yen-Chao Lin, Thy Anne Chu Quang and Kate Whiteway (and, previously, Amanda Nguyen, Linx Selby and Cynthia Or). Set up as an arts organization, the group attempts to subvert the contemporary art world by posing as a legitimate entity while in actuality running rogue events with little communication output. One such event was “A Glass House Should Hold No Terrors,” an exhibition in August 2016 held in Montreal’s abandoned Royal Victoria Hospital mountainside pool.

Céladon is the colour of a transparent glaze that originates in China (though the term is European) characterized by tiny, baked-in cracks. The metaphor—that the collective’s work, like its namesake, brings a characteristically non-Western outlook to the art world by creating and operating in its cracks—is apt. The members of Atelier Céladon include researchers, writers, artists, dancers and activists; anyone can join the online community. While most actions are planned by the core group, any member can propose a project. Given the art world’s reputation of exclusivity, this openness registers as nothing short of radical. Using friendship as a methodology, Atelier Céladon does not emphasize production and instead focuses on skill-sharing and creating an environment of care.

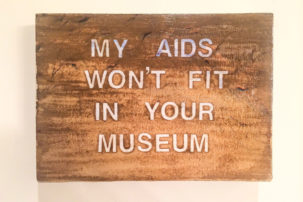

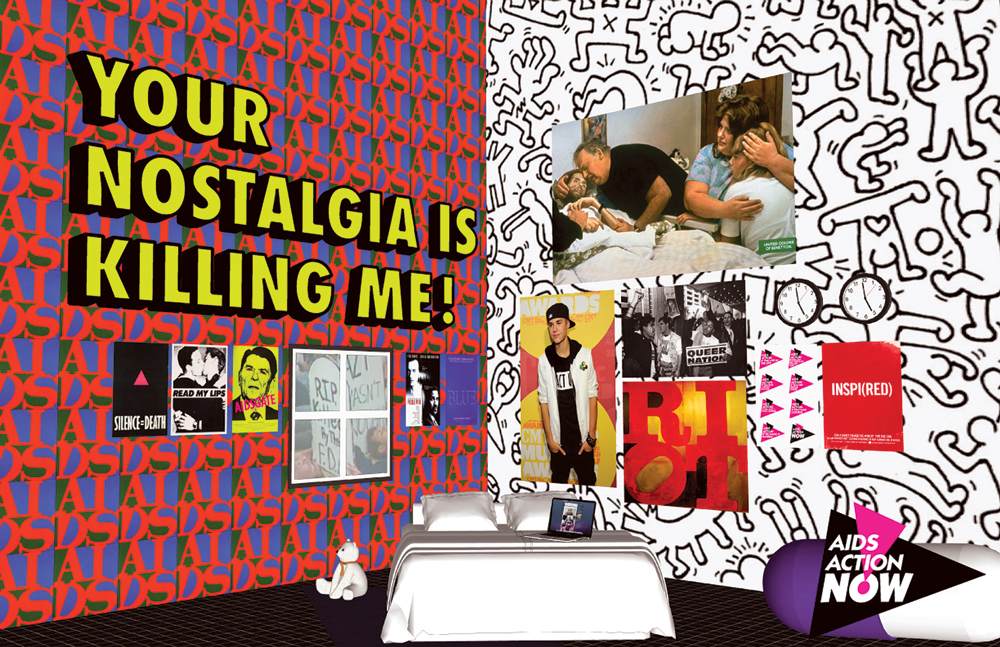

Vincent Chevalier (with Ian Bradley Perrin), Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me, 2013. Digital image.

Vincent Chevalier (with Ian Bradley Perrin), Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me, 2013. Digital image.

Vincent Chevalier

Vincent Chevalier is best known for work that explores his relationship to HIV/AIDS. As an HIV-positive gay man, he has studied both his medical and personal history to develop an auto-ethnographic practice rooted in the language of post-internet visual identity, often with a nod to Canadian video pioneers and performance artists working on similar material. These highly successful works, including So… When did you figure out that you had Aids?, Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me! and Places Where I Fuck’d, come at a high personal cost. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to foster self-care and wellness when you are always on—always performing, always working—and when your identity is invested in your artwork. In our current economic reality, where suffering is a form of currency, pain is a labour output and payment is often simply prestige.

Moving forward, Chevalier is refusing to take on projects that effectively entertain via his own experience of trauma. In his 2016 work À Vancouver—a father-son travel movie shot on a cross-country road trip—Chevalier focuses on an unspoken act, alluding to the artist’s first sexual experience at the age of 11. Revisiting the autobiographical material, even in a fictionalized context, reopens old wounds. The sensational subject acts as a hook for the audience, but it also re-traumatizes the artist. His new work departs from that type of nostalgia and develops ways of seeing and being together pluralistically.

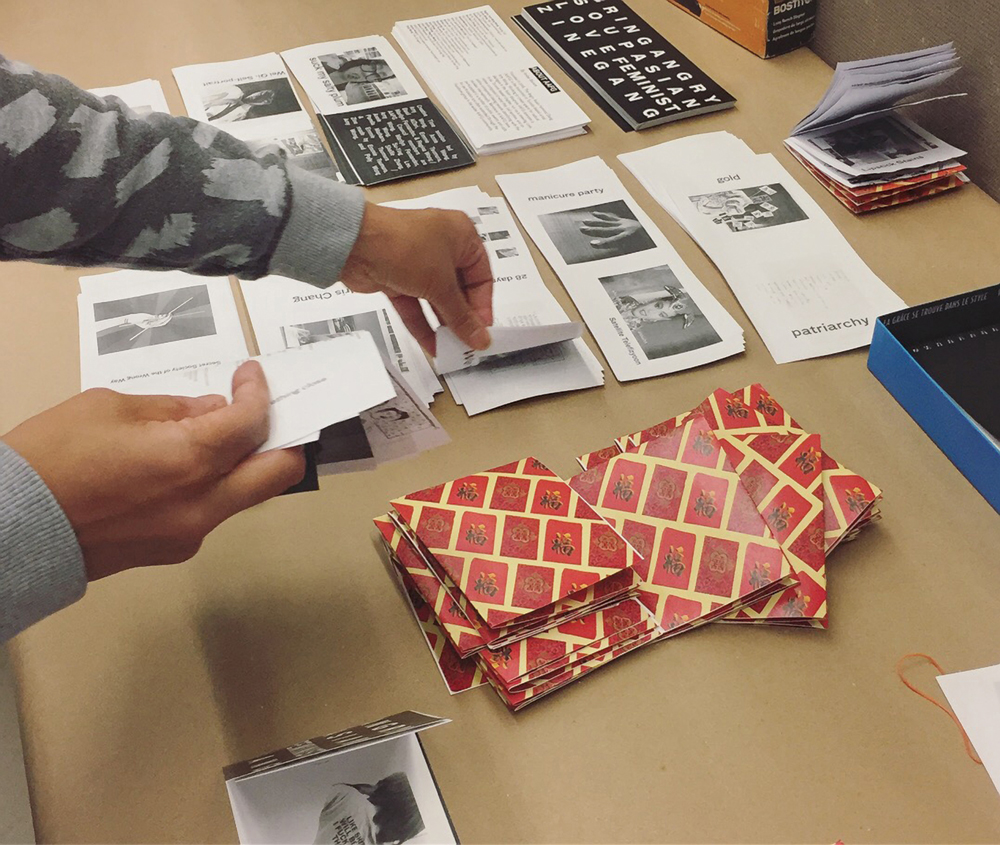

Assembling the Angry Asian Feminst Gang’s Bring Soup Love zine at the Creative Time Summit, Toronto, September 2017. Photo: Shellie Zhang.

Assembling the Angry Asian Feminst Gang’s Bring Soup Love zine at the Creative Time Summit, Toronto, September 2017. Photo: Shellie Zhang.

Angry Asian Feminist Gang

The Angry Asian Feminist Gang (AAFG) is the brainchild of Toronto artist Amy Wong. Conceived in 2016 as a means of creating space for radical dialogue in the Asian diaspora, AAFG operates a local, Toronto-based chapter—run via a steering committee composed of what they call “aunties”—as well as an online component linking people identifying with the moniker internationally. The collective also seeks to act in solidarity with other marginalized voices, aiming to ally their work in support of members of BIPOC communities.

In a recent anti-oppression workshop, AAFG: Bring Soup Love, at the Creative Time Summit in Toronto, Wong and other AAFG members invited the public to collaboratively make a healing bone broth called sey mei tong, following Wong’s family recipe. To prepare for the project, Wong, her mother Regina and her sister Polly visited herb shops in Chinatown to purchase ingredients for soup care packages distributed to workshop attendees. She also included business cards from one of the shops as a means of inviting participants into these spaces and as a gesture of reciprocity. For Wong and the members of AAFG, the act of collective cooking offers a shared experience of the relationships between gendered and racialized knowledge, and a signal of communal care toward the effects of historically unresolved grief and trauma.

Skeena Reece, There is time for love, 2016–17. Fabric, beads, cradleboard and dried moss. Dimensions variable. Courtesy OBORO. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Skeena Reece, There is time for love, 2016–17. Fabric, beads, cradleboard and dried moss. Dimensions variable. Courtesy OBORO. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Skeena Reece

Handmade moss bags, similar to swaddle blankets, are meant to carry a baby, and are items synonymous with comfort. The bags are attached to cushioned cradleboards and are often carried on a parent’s back. Like most handmade baby items, the bags are a representation of the love and care that the family and community gives the newest member. Skeena Reece, a Vancouver Island–based artist, has created an adult-sized moss bag, which must be shown on the floor or hung on a wall. While the bag can support a human, no body exists to carry a moss bag so large on its back. The suggestion of comfort is therefore compromised through the realities of physics, even though we are still in need of compassion and nurturing as adults. The bag can never actually provide care and comfort for its intended recipient.

Reece calls herself a trickster, and her work is always infused with humour, even while challenging the audience to work through difficult ideas. She considers her work to be about love, but also about the ongoing process of care; nurturing is not merely a phase in anyone’s life. While the moss bag can certainly be read as a work about reconciliation, Reece’s refusal of one-dimensional readings complicates this interpretation with humour and love.

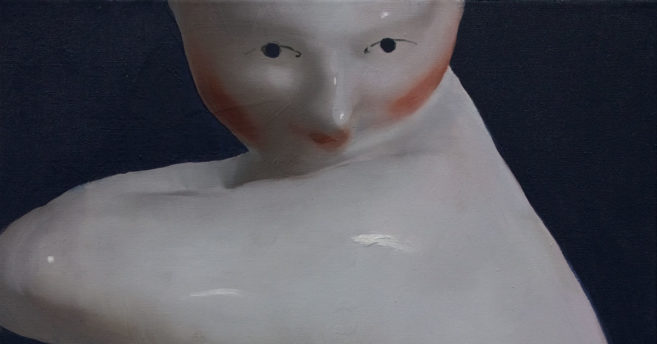

Ambera Wellmann, Love Fingers, 2017. Oil on linen, 1.47 x 1.37 m. Courtesy of TrépanierBaer Gallery.

Ambera Wellmann, Love Fingers, 2017. Oil on linen, 1.47 x 1.37 m. Courtesy of TrépanierBaer Gallery.

Ambera Wellmann

Berlin-based, Canadian painter Ambera Wellmann is interested in the way that work that sits in the past can come to be the present. The 2017 RBC Canadian Painting Prize Competition winner’s work is sensuous, erotic and decadent. Her paintings investigate the historical affect of the body as object, and the representation of the female form. By positioning the body as central in her paintings, both on linen and wood, Wellmann uses history in an attempt to destroy the canon. Her work is unabashedly feminist, challenging the viewer to think about whose gaze we perform for.

These intimate interactions on the canvas both challenge and maintain a legacy of the female body as an object to be consumed. This is troubled by Wellmann’s ongoing photographic series on Instagram. In these images, Wellmann uses her own body to playfully tease viewers’ expectations. In one, she places her iPhone over her vulva, displaying an image of a black cat. In another, she creates the illusion of breasts in lingerie by placing a bra over her back and elbow. The images place her in dialogue with the large community of digital feminists working at intersections of theory and practice. With more than 39,000 followers and growing, Wellmann is leading a discussion around women’s bodies and the external and internal gaze.

Jamie Ross, The Pyre, 2016. Performance documentation 27.9 x 43.1 cm. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Jamie Ross, The Pyre, 2016. Performance documentation 27.9 x 43.1 cm. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Jamie Ross

Jamie Ross is a video artist based in Montreal. He is also a Pagan chaplain who volunteers in Quebec’s men’s prisons. Recently these elements of his life intersected when he worked on a project with artist-run centre Verticale, in Laval, that brought his work with prisoners into the gallery as an act of solidarity and an expression of the resilience of witches in prison. For Ross and the men he works with, this gesture goes beyond art as therapy—it is a means of support and a space for dialogue with those whose voices are being increasingly silenced.

In a prison system navigating underfunded psychiatric and social services, and overwhelmed by a mental-health crisis, chaplains increasingly serve the dual role of spiritual leader and therapist. In a society where people often outsource wellness services because their needs are ignored by traditional Western medicine, Ross’s paratherapeutic model proves the ways an artist and activist can create and widen the smallest of cracks that allow care to happen in even the most inhumane circumstances.

Amber Berson is a writer, curator and PhD student conducting doctoral research at Queen’s University on artist-run culture and feminist, utopian thinking. Her most recent curatorial projects are “Utopia as Method” (2018), “World Cup!” (2018) and “The Let Down Reflex” (2016–17, with Juliana Driever).

This post is adapted from the feature article “Taking Care,” generously supported by RBC in the Winter 2017 issue of Canadian Art. RBC is passionately committed to supporting emerging artists across Canada and internationally, and is proud to partner with Canadian Art on this Spotlight series.

This post was corrected on February 5, 2018. The original copy erroneously stated the scope of Jamie Ross’s work with prisoners. Canadian Art is responsible for this error and apologizes for any confusion it may have caused.