Generously supported by RBC

when my kokum smiles

the wrinkles that gather at the corner of her eye

are rivers

leading me home.

—Samantha Marie Nock, “Pipon,” 2016

Rivers and streams—constellations written on the land, connecting and diverging—lead us to our various homes. Thinking of kinship, I see patterns of relationships, a spiderweb of stars and planets—families, friends, those who inspire us—supporting us as we walk our paths. Each of us has multiple, interconnecting networks of kin that are linked to us through blood, others through friendship, still others through common interests or geography. However the pattern emerges, these networks surround us in communities that challenge and support, focus and inspire.

I have approached this spotlight as a curatorial project in which I use constellations of kin and visiting as a methodology. As a curator and researcher I understand that my relationship with Indigenous art is informed by the connections I have made with others who have supported me through conversations. I have reached out to that network and have asked them to connect me to emerging artists whose work engages with ideas of kin.

Throughout this process, I was linked to a wide range of incredible Indigenous artists on Turtle Island. I have used what Wiisaakodewinini/Métis artist, activist and writer Dylan Miner terms “methodologies of visiting”: an Indigenous way of knowing that emphasizes visiting, storytelling and love, and that focuses on the importance of oral knowledge and time spent together as a way of building and maintaining communities and relationships, and asserting Indigenous sovereignty. I spoke with many of the artists suggested to me, and through this process created new relationships and broadened the network to which I am already connected. This project, then, explores the ways in which a number of emerging artists are investigating ideas of kin and community. Through this process of introducing the work of artists, I map out a constellation of relationships within the very broad and diverse field of Indigenous arts.

Lindsay Dobbin, Listener Ship, 2016. Documentation of performance with found natural materials and wood debris.

Lindsay Dobbin, Listener Ship, 2016. Documentation of performance with found natural materials and wood debris.

Lindsay Dobbin

Lindsay Dobbin’s practice is one of deep listening. Dobbin is a mixed Indigenous (Mohawk)/settler artist who is based on the Bay of Fundy. In their artist statement, Dobbin describes their practice as place-responsive—deeply rooted in collaboration with the land. Recent works include Listener Ship (2016), in which the artist built an outdoor studio of found wood in the forest outside the Banff Centre during their Indigenous Visual and Digital Arts Residency in January 2016. Made in snowy, minus-30-degree weather in less than a week’s time, Listener Ship illustrates Dobbin’s wilful commitment to making work in tune with the elements. Dobbin invited guests to the studio to sit together and hear the land. The land holds incredible knowledge that is often drowned out by the noises of everyday life and industry. Listener Ship provided a space to spend time with the land and one another, in the important act of listening.

Meagan Musseau, Made in Ktaqamkuk(stills), 2016. Sound and video installation. Dimensions variable.

Meagan Musseau, Made in Ktaqamkuk(stills), 2016. Sound and video installation. Dimensions variable.

Meagan Musseau

Meagan Musseau is an interdisciplinary artist of Mi’kmaq and settler ancestry from the Bay of Islands, Ktaqamkuk (Newfoundland). Her video installation Made in Ktaqamkuk (2016) explores the Indigenous connections to the land now called Newfoundland, and the tensions of belonging that exist in First Nations communities on the island as a result of recently being included in the Indian Act. Recounting oral knowledge and stories passed down to her by her grandmother and other family members, Musseau narrates footage of her walking on the land. The land holds her family’s stories—the knowledge of her ancestors who walked on it since time immemorial. Musseau’s installation examines the ways in which land knowledge and familial knowledge constitute belonging outside of colonial identity.

Melissa General, Nitewaké:non (detail), 2015. C-print. Dimensions variable. Courtesy Harbourfront Centre.

Melissa General, Nitewaké:non (detail), 2015. C-print. Dimensions variable. Courtesy Harbourfront Centre.

Melissa General

Each of Melissa General’s works are made on—and reference her connection to—Six Nations of the Grand River territory. As a Six Nations member currently living in Toronto, General centres her practice on connection to place and relationship to land. In her 2015 work Nitewaké:non, General examines the constant pull she feels to return home. Unearthing a long bolt of red cloth she had buried, General wrapped herself in the cloth, breathing in connection with the knowledge held in the land. The series of photographs that make up the work show General wrapped in the cloth, standing among the bushes, on the land of her ancestors. As she smells and feels and sees the land, General activates its memories and its knowledge, acknowledging those who call her back to Six Nations.

Couzyn van Heuvelen, Avataq, 2016. Screenprinted mylar, ribbon, aluminum and helium. Courtesy Fazakas Gallery.

Couzyn van Heuvelen, Avataq, 2016. Screenprinted mylar, ribbon, aluminum and helium. Courtesy Fazakas Gallery.

Couzyn van Heuvelen

Couzyn van Heuvelen is an Inuk sculptor originally from Iqaluit, Nunavut, and currently living in southern Ontario. Van Heuvelen’s practice centres on exploring Inuit technology using non-traditional materials. Coming from a family of makers in the North but spending much of his time in the south, van Heuvelen says that his practice of creating hybrid objects allows him to access his Inuit culture while also exploring the ways in which traditions influence everyday life. He plays with notions of scale and automation, making harpoon tips and fishing lures in silver and bronze, and using 3-D modelling software and scans of polar bear and walrus skulls. These works reference both Inuit miniature sculpture and the use of ivory and bone in Inuit art and technology. By repurposing raw materials of silver and bronze to reference traditional materials that are increasingly difficult to access, the artist raises questions of material value, hybridity and connection to kin through making.

Jennie Williams,Nalujuk Night in Nain, 2016. Digital photograph. Dimensions variable.

Jennie Williams,Nalujuk Night in Nain, 2016. Digital photograph. Dimensions variable.

Jennie Williams

Community, and portraits of an isolated but happy North, are key to the work of Inuk artist Jennie Williams. Originally from Happy Valley–Goose Bay, and now living in Nain, Williams uses photography to document community traditions and the everyday life of Labrador Inuit living in the area. In her ongoing documentary series Nalujuk Night (2011–), Williams archives years of her community celebrating the Moravian/Inuit tradition of Nalujuk Night, or Old Christmas Day. Nalujuk Night takes place annually on January 6, when the Nalujuit come out to playfully terrorize and taunt the community. The Nalujuit are boogeyman-type figures used to teach lessons to Inuit children in Northern Labrador. On Old Christmas Day, anonymous individuals dress as Nalujuit in tattered atigik (parkas) with masks, and chase after the gathered community.

Williams’s images of Nalujuk Night capture a unique experience of Labrador life. As in many of her other photographic works, Williams—who was recently in residence at the Rooms in St. John’s—aims to celebrate the strong connections built within her isolated northern community through play, tradition and gathering. Her photographs, she says, start a conversation about the lived realities of Northern Labrador communities and create space for the sharing of stories and traditional knowledge.

Jeneen Frei Njootli,LUX | MAM I , 2016. Red latex and caribou antler. Courtesy Macaulay and Co. Fine Art. Photo: Barb Choit.

Jeneen Frei Njootli,LUX | MAM I , 2016. Red latex and caribou antler. Courtesy Macaulay and Co. Fine Art. Photo: Barb Choit.

Jeneen Frei Njootli

A member of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation in the Yukon, Jeneen Frei Njootli is an interdisciplinary artist currently living in Vancouver. Her recent series of performances, installations and sculptures, LUX | MAM (2016–17), stem from being unable to pull-start a ski-doo with her aunt when she visited her Yukon home. Upon moving to Vancouver, Frei Njootli found that her physical strength, and the knowledge inherent in that strength gained from living on the land, waned as she spent more time with books by Gramsci and others. And so Frei Njootli activates composite exercise equipment—a beaded skipping rope in a Gwitchin mitt string pattern, exercise mats—to examine the hegemony of Western knowledge systems and the scholarly theorizing of labour. By using this equipment in front of an audience—and leaving behind ephemera—Frei Njootli points to the fetishization of Indigenous labour and knowledge. Collaboration is also key. Her performance with Tsema Igharas (see pages 77 and 86) explores the relationship between Indigenous communities and industry through the motif of the braid. Frei Njootli and Igharas braid their hair together with strands of rope and neon flagging tape, creating two umbilical cord–like jump ropes that speak to the inoculating influence of kinship against resource extraction in Indigenous communities.

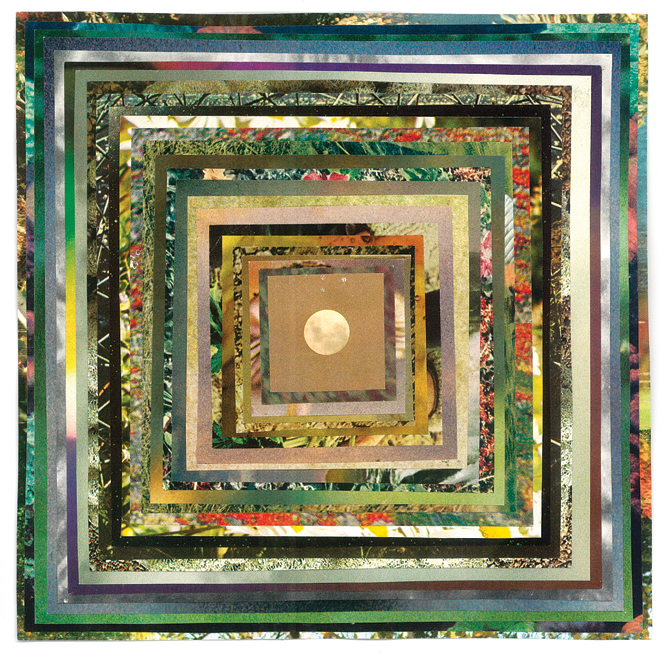

Maggie Groat, All Things Under Influence of the Moon I, 2014. Collage. Courtesy Erin Stump Projects.

Maggie Groat, All Things Under Influence of the Moon I, 2014. Collage. Courtesy Erin Stump Projects.

Maggie Groat

Maggie Groat is a St. Catharines–based artist who works in a variety of media, including works on paper, site-specific interventions, sculpture, textiles and publications. Through an Indigenous (Skarù:re?)/settler lens, Groat explores salvage practices, shifting territories and alternative and decolonial ways of being. In her collage All Things Under Influence of the Moon II (2014), Groat investigates cycles, balance and celestial knowledge. The piece considers the ancestral and power relationships of the moon and its influence over our bodies and all matter of life. Groat writes that All Things explores the ways in which the moon guides her, affects and times her body and the natural elements around her. The moon casts light on our darkness and represents faraway, obscured knowledge. All Things explores alternative ways of seeing and finds comfort in not knowing.

Jessie Short, Wake Up! (production still), 2015. HD/4K video. 5 min 58 sec. Photo: Alexander Sakarev.

Jessie Short, Wake Up! (production still), 2015. HD/4K video. 5 min 58 sec. Photo: Alexander Sakarev.

Jessie Short

Jessie Short is a Métis performance artist, writer, curator and filmmaker currently living in Calgary. Frustrated by ignorance of Métis identity as distinct, Short engaged film and performance in a statement of presence at M:ST Festival in Calgary in October 2016. In her performance We’ve (2016), Short fingerweaved a neon-coloured Métis sash onto the arm of a statue of well-known Canadian Nellie McClung, a women’s-rights activist and suffragist. (McClung was one of the “Famous Five” who initiated the Persons Case of 1928–29, granting women the legal status of “persons” under the British North America Act. Yet McClung and the international suffragist movement also tended to exclude Indigenous women and women of colour.)

Weaving the neon yarn onto the wrist of the statue—which can only be removed if cut away—Short used her unique take on traditional practice to assert presence and belonging as a Métis woman. The video installation accompanying the performance, Wake Up! (2015), documents the artist as she transforms herself into Métis leader Louis Riel. In another, longer version of the video, a voiceover asks, “Do you know who Métis people are? Have you heard of Louis Riel? Well, I’m kind of like him.” Short appropriates the image of Riel to make her voice heard and to, in her words, “make Métis real for people.”

Tsēma Igharas Riot Rock Rattles, 2016 Copper, rawhide and ceramic shell containing glass beads, dentalium shells, penny shards and Mount Edziza soil samples Dimensions variable. Photo Jonathan Igharas

Tsēma Igharas Riot Rock Rattles, 2016 Copper, rawhide and ceramic shell containing glass beads, dentalium shells, penny shards and Mount Edziza soil samples Dimensions variable. Photo Jonathan Igharas

Tsēma Igharas

Tsēma Igharas is an interdisciplinary artist and a member of the Tahltan First Nation. Igharas describes her methodology as Potlatch, a ceremony of reciprocation and nation building. Igharas writes that she understands her practice through the lens of Potlatch, in which every performance of artmaking is a “ceremony that affirms and solidifies relationships to every thing and body.” In her recent graduate exhibition, “LAND|MINE” (2016), at OCAD University, Igharas enacted these strategies of reciprocation and connections to land, with the goal of transferring “concepts and knowledge so the viewer can contemplate ideologies related to [land] beyond the white cube.” Focused on transferring knowledge about notions of land, as well as bridging Toronto and Tahltan territory, Igharas created a material library of rocks, copper, ceramics, construction orange, mirror and obsidian—materials that reference her Tahltan home. This library, and the performance Khohk’ätsskets’mä (2016), which activates them, affirm Igharas’s relationship to the land, its materials and its people.

Kite Everything I Say Is True, (detail) 2017 Dress documentation Courtesy Walter Phillips Gallery. Photo: Amanda Farmer

Kite Everything I Say Is True, (detail) 2017 Dress documentation Courtesy Walter Phillips Gallery. Photo: Amanda Farmer

Kite

Oglala Lakota artist Kite says much of her work addresses her distance from family, family knowledge and truth. As a Lakota person adopted outside of the tribe, Kite writes that her work “consistently springs out a feeling that I can get infinitely close to land/family/territory/tribe but they are just barely outside of my grasp.” In her newest performance and installation, Everything I Say Is True (2017), Kite attempts to get close to her family, the land and histories connected to Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota, where many of her relations live, mapping them on a dress made of concentric rings that she wears. The nesting rings communicate Kite’s theory of time as non-linear and the closeness of past and present. Exploring understandings of truth and contrasting Western and Lakota conceptions of time, the Los Angeles–based Kite performs her relationship to Pine Ridge. Locating herself among historical events, places and family, plotted as data points on the rings of her dress, Kite attempts to get close to not only who she is, but also where she is.

This post is adapted from the feature article “Constellations,” generously supported by RBC in the Summer 2017 issue of Canadian Art. RBC is passionately committed to supporting emerging artists across Canada and internationally, and is proud to partner with Canadian Art on this Spotlight series.

To get every issue of our magazine delivered to your door before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.