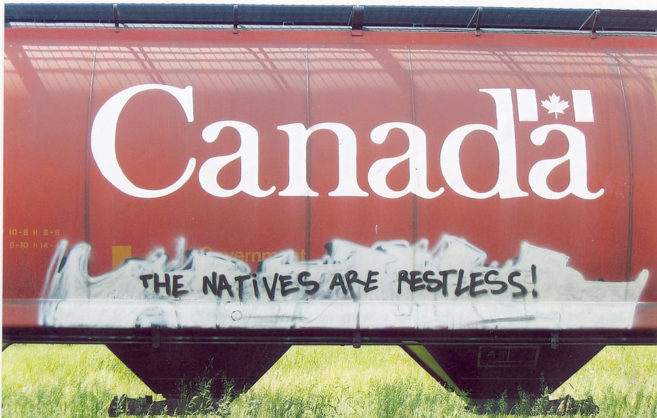

From funding for major new arts events to spurring of political resistance among Indigenous artists and allies, the federal government’s Canada 150 proclamation has affected many sectors of the art world so far this year.

And as of this week, the auction field is no exception. On June 27, Waddington’s auction house in Toronto held what it called “The Canada 150 Auction.” The 190 lots in this sale ranged from tiny silver snuff boxes to massive acrylic paintings, and from 400-year-old Maritime maps to 28-year-old Skydome tickets.

Here are 12 interesting lots from the auction—all of which found ready buyers.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Norval Morrisseau’s Shaman Astral Guide I and Shaman Astral Guide II (Estimated at $50,000 to $60,000, sold for $60,000)

Each of the canvases in this 1978 diptych measure three metres high, providing a prime example of work by the man credited with creating the Woodland School style. Morrisseau, who was Anishinaabe and self-taught, said that “all my painting and drawing is really a continuation of the shaman’s scrolls.” Early on, he also painted on birchbark and moose hide, among other materials.

Given the critiques that many Indigenous artists and allies have made of Canada 150 in recent months, it is worth remembering that Morrisseau, in his day, also confronted issues of erasure and censorship. He was asked to be part of the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo 67—and ended up leaving the project when government officials, as Carmen Robertson puts it, “deemed his mural design of bear cubs nursing from Mother Earth to be too controversial.” The pavilion itself still took a critical slant after Morrisseau’s mural was finished (in altered form, by another artist) with visitors being greeted by the phrase “You have stolen our native land, our culture, our soul…” and other truths.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Convention of London, Canada-United States Cast Iron Obelisk Form Border Marker, 19th Century (Estimated at $5,000 to $7,000, sold for $18,000)

A great many historical, somewhat utilitarian, items were available in this auction, and this is the one that went for the highest price: a marker that was erected along the border between the US and Canada in 1861. Made of cast iron, and reaching some two-and-a-half metres high, the marker/obelisk was one of 8,600 placed along the border that year. (Some of the other markers installed were granite, bronze and stainless steel.)

The Convention of London—whose signing date, October 20, 1818, is printed in raised letters on the obelisk—was, as the Canadian Encyclopedia puts it, “a treaty between the United States and Britain that set the 49th parallel of latitude as the boundary between British North America and the US across the West. This remains the boundary today between the two nations.”

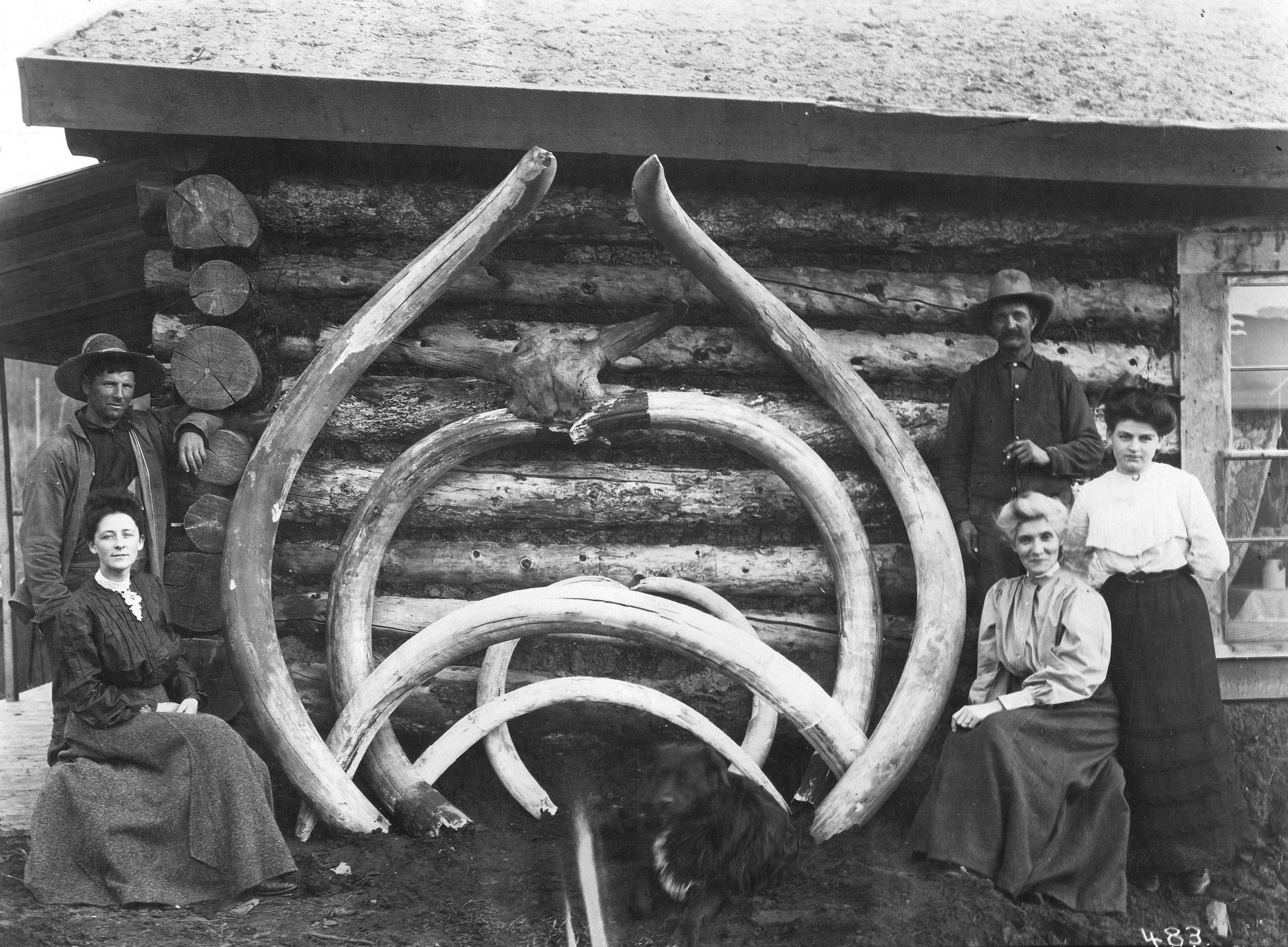

This circa-1906 image from the City of Vancouver archives shows tusks recovered from Yukon Territory.

This circa-1906 image from the City of Vancouver archives shows tusks recovered from Yukon Territory.

Woolly Mammoth Tusk from Yukon Territory (Estimated at $3,000 to $4,000, sold for $9,000)

Some fossils are found in museums, others stumbled upon by hikers at trailside or by engineers on a mine site. Though it is uncertain exactly where this tusk came from, and who initially found it—it is now heavily polished, and comes with its own presentation stand—it is said to be from the Yukon and the Devensian Period, roughly 110,000 to 12,000 years ago.

As the Yukon’s Beringia Interpretive Centre notes, “These large, furry elephants were perfectly adapted to living on the Mammoth Steppe of ice age Yukon.…The long, curved tusks of woolly mammoths are probably the most immediately recognized ice age fossil from Yukon. A single tusk from an adult male can stretch over 3.5 metres long and weigh more than 100 kilograms. These tusks may have been used for display, defense, or possibly to sweep away snow to get at grass in the winter.”

Courtesy of Waddington’s

Courtesy of Waddington’s

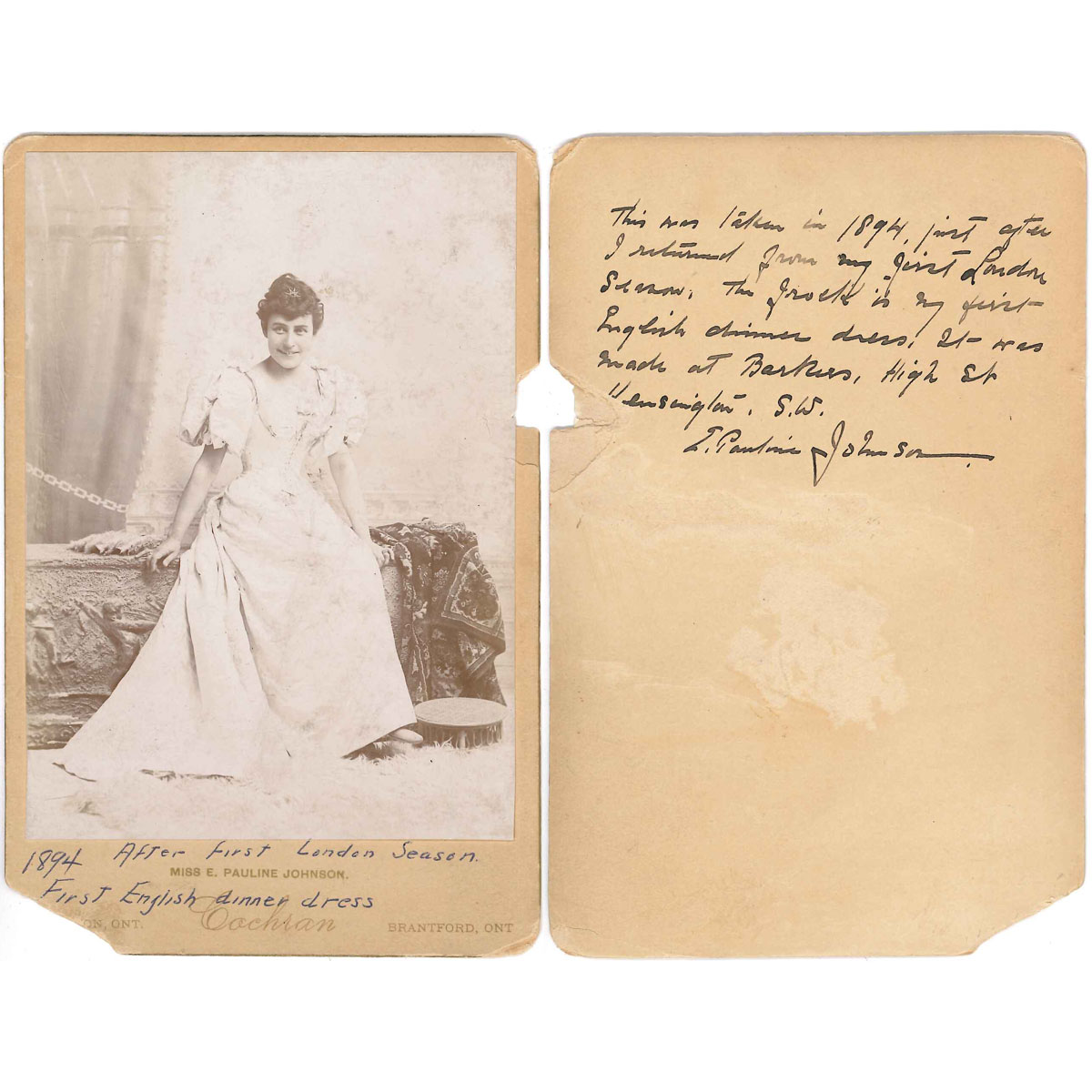

E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) Signed Portrait Cabinet Card (Estimated at $200 to $300 and sold for $960)

“This was taken in 1894, just after I returned from my first London season. The frock is my first English dinner dress. It was made at Barkers, High St., Kensington S.W.”

So reads the handwritten note on the back of this portrait of E. Pauline Johnson (1861–1913), the daughter of a Mohawk father and an English mother, who some say was Canada’s first spoken-word star. She was also known as a writer, artist and performer, penning such famous poems as “The Song My Paddle Sings,” and the 1903 book Canadian Born, which reportedly sold out within a year.

Born the youngest of four children on the Six Nations reserve near Brantford, Johnson took early to “reading and writing of rhymes,” the 1916 book Canadian Poets states. Her breakthrough performance came in Toronto in 1892 of her own poem titled “A Cry From an Indian Wife,” which told the story of the North-West rebellion from a First Nations point of view. As this cabinet card indicates, once she became established, Johnson travelled to the UK to perform as well as across Canada.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Arthur James Donahue’s Winnipeg Chair (Estimated at $500 to $700, sold at $3,840)

Originally crafted in the basement of Arthur James Donahue’s Winnipeg home with the help of his architectural design students at the University of Manitoba, the Winnipeg Chair was originally sold for $35 at the Hudson’s Bay Company. The mid-century piece was also then available in colours including orange, mustard and lime green. This one is leather-upholstered on laminated wood and an iron frame—now, a collectors’ item.

Born in 1917 in Regina to a family oriented towards farming and business, Donahue went on to, as the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation puts it, become the “the first Canadian to complete a degree at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.” There, he was influenced by Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius. His 1940s designs for fibreglass stacking chairs, which never went into production, were similar to those introduced a few years later by Charles Eames. Donohue’s larger-scale projects include the Confederation Building in Charlottetown, the Monarch Life building in Winnipeg and the Nova Scotia Archives in Halifax.

Courtesy of Waddington’s

Courtesy of Waddington’s

Pierre Elliott Trudeau Campaign Dress (Estimated at $1,000 to $1,500, sold for $2,880)

If one needed any more evidence for the frenzy that was Trudeaumania 1.0, here it is: a sleeveless A-line dress of printed cellulose fabric. Not only fashionable (to some), it also served as a wearable campaign poster for Trudeau’s 1968 Liberal leadership bid and the related party convention that year.

Following his win at that leadership convention in April, Trudeaumania continued to build, and the Liberals won the federal election later that year as well. Trudeau would go on to become the longest-serving prime minister of anyone before him, holding that post from 1968 to 1979 and 1980 to 1984.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Collection of 13 World War II Propaganda Posters (Estimated at $300 to $400, sold for $3,120)

It seems that history buffs and design buffs alike love a good wartime propaganda poster. This lot of posters from 1943 fetched 10 times its low estimate at auction. Each poster measures roughly 33 inches by 22 inches, and each seems to emphasize strengthening a connection between Canadians’ efforts at home with those of Allied soldiers in Europe.

Slogans include “He’s doing his part are you doing yours?” “It’s Our War” and “To Victory! With Our Help” as well as French versions, like “Allons-y… Canadiens!” for a bilingual populace. As exhibitions at the Canadian War Museum have noted, “The creators of [propaganda] exploit the power of words and images to construct persuasive visual messages that evoke feelings of fear and anger, pride and patriotism. In proposing or privileging one point of view to the exclusion of others, propagandists during the two world wars were neither the first nor the last to manage information in this fashion. It is as much a part of our contemporary world, in commercial advertising or political campaigning, for example, as it was a part of the Roman Empire over 2,000 years ago, when emperors and generals manipulated their images and accomplishments in order to secure or attain power.”

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

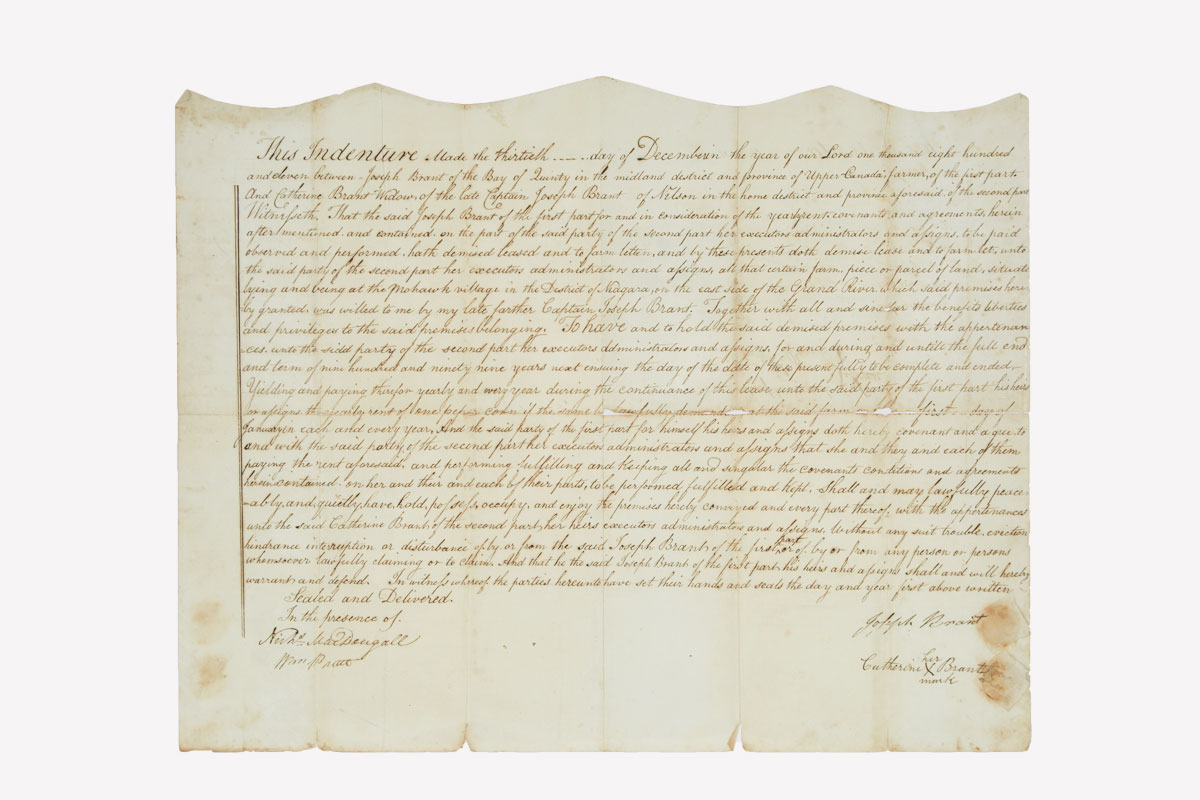

Terkarihogen (Joseph Brant) Lease to Ahdohwahgeseon (Catherine Brant) (Estimated at $300 to $400, sold for $3,600)

Mohawk military and political leader Thayendanegea (1742–1807), also known as Joseph Brant, fought throughout the American Revolution with an Aboriginal-Loyalist band, the Canadian Encyclopedia notes. Then, when American independence displaced him from his Mohawk Valley homeland, he moved to a territory provided as compensation by the British on the banks of the Grand River in Ontario. There, he spent several years working “to form a united confederation of Iroquois and western Aboriginal peoples in order to block American expansion westward.”

When Thayendanegea died in 1807, he willed his farm to his son Terkarihogen (Joseph “John” Brant). In 1811, this son leased it back to his mother Ahdohwahgeseon (Catherine Brant), who returned to live there for the rest of her life. The lease is created in quill on laid paper, and is signed by the younger Joseph Brant, as well as Catherine Brant, and witnesses. Thayendanegea is the namesake for present-day city of Brantford, where both his and his son’s remains are interred at the burial grounds around the Chapel of the Mohawks.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

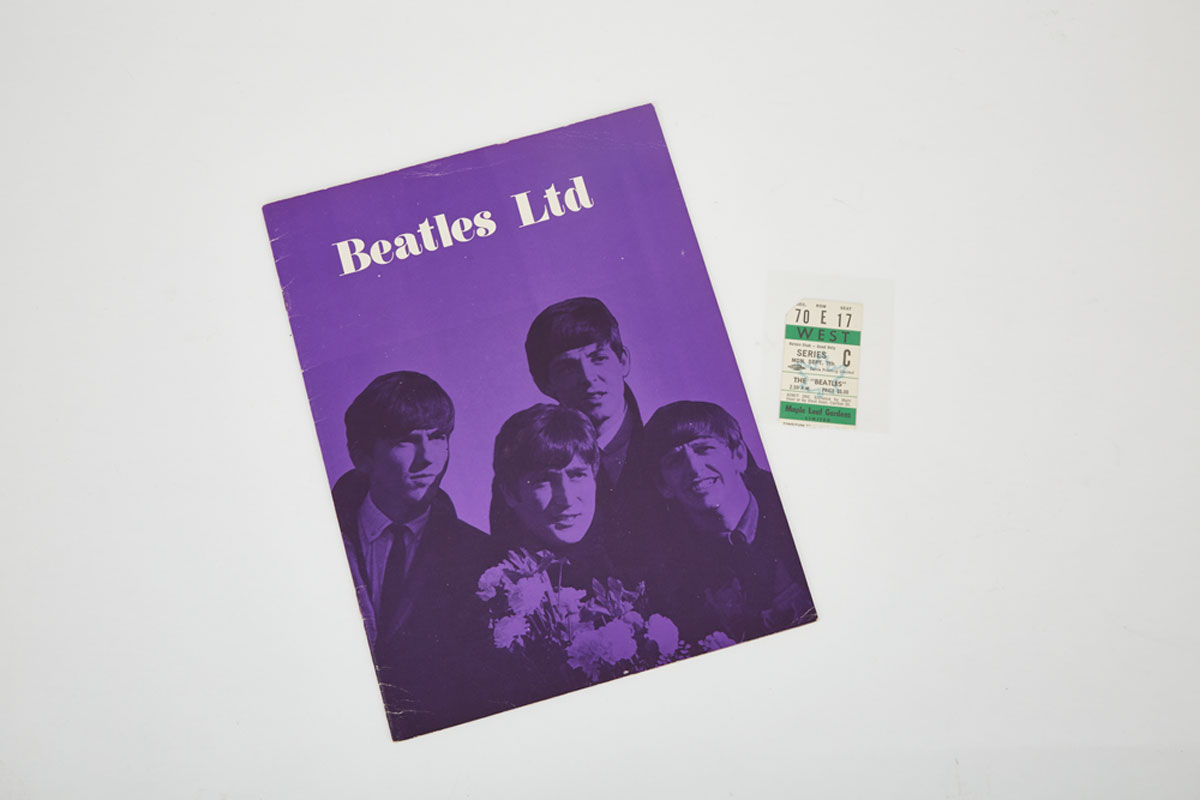

The Beatles First Concert at Maple Leaf Gardens Ticket and Programme (Estimated at $100 to $150, sold for $2,460)

From Trudeaumania to Beatlemania, this auction spanned it all. This souvenir is from the Beatles’ September 7, 1964 concert at Maple Leaf Gardens. It is claimed that Toronto was actually home to the largest organized Beatles fan club in North America at one point, and perhaps that is true; on this particular visit, the Beatles played two shows (one at 2:30 p.m. and one at 8:30 p.m.) selling 35,522 tickets, says the Beatles Bible. (The ticket in this auction lot was for the afternoon show, originally priced at $5.00).

When the band arrived at the King Edward Hotel from the airport, they reportedly found a 14-year-old girl hiding in a linen closet. At the Gardens, 4,000 police officers and Mounties were on duty, and a five-block surrounding area was sectioned off for 12 hours before the group’s arrival. The Beatles returned to Maple Leaf Gardens on only two other occasions: 17 August 1965 and 17 August 1966.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Kenojuak Ashevak Owl’s Bouquet (Estimated at $2,000 to $3,000, sold for $6,600)

This 2007 stonecut and stencil on paper contains an image that Canadians will be seeing a lot more of this year, as a 10-dollar bill featuring a replication of Owl’s Bouquet was recently unveiled by the Bank of Canada for general currency circulation during Canada 150.

Kenojuak Ashevak (1927–2013) is the first Inuit artist to have work on a Canadian banknote. It’s just the latest nod to this artist’s influence and legacy; in 1970, her print for the Enchanted Owl was featured on a postage stamp, and last year, she was honoured with a Heritage Minute. Ashevak was one of the first women involved with the Cape Dorset Co-op. During her lifetime, she also received the Order of Canada and the Order of Nunavut, and was exhibited at many international locations.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Vincent Massey’s Top Hat (Estimated at $300 to $400, sold for $1,680)

Among his other achievements—like initiating the tradition that all Governor Generals be Canadian citizens—Vincent Massey (1887–1967) is perhaps best known in the arts for major initiatives of his that continue to have impact, such as the annual Massey Lectures and the 1951 Massey Report, which led to the establishment of the Canada Council. These initiatives came in his seven years as Governor General from 1952 to 1959.

Massey’s legacy is not without controversy and documented bias, however. The award-winning 2012 book None is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948 states that in the late 1930s, Massey tried to use his influence as scion of a wealthy family to keep Jewish refugees out of Canada, advocating to the Prime Minister that Canada boost refugee status for non-Jewish Eastern European migrants instead. Wikipedia also notes that “His donation of Hart House to the University of Toronto stipulated that the building be restricted to men only, and it was not until after his death that the deed of gift was altered to allow for women becoming full members in 1972.”

This circa-1940 top hat, along with leather case and travel pillow, came from Lock & Co. Hatters on St. James Street in London, and perhaps can be read as representative of the colonizer costumes and morays woven together in Massey’s history, and his impact.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

Courtesy of Waddington’s.

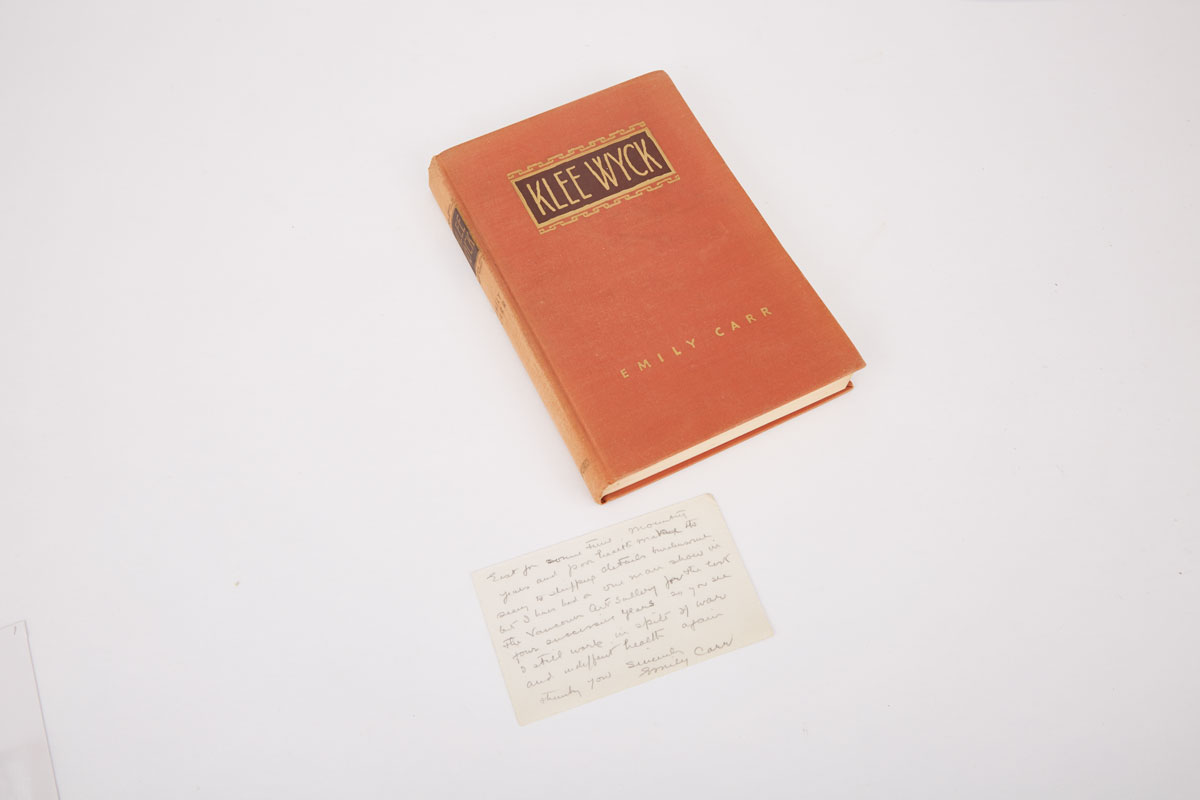

Emily Carr’s Klee Wyck Book and Note (Estimated at $100 to $150, sold for $1,800)

Old books were a prominent feature of this auction, with volumes including a first edition of L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, a 1925 edition of Wilfred Thomason Grenfell’s A Labrador Doctor, and a 1869 edition of Catherine Parr Traill and Agnes Fitz Gibbon’s folio Canadian Wild Flowers.

This first edition of Emily Carr’s Klee Wyck, published in 1941 and winner of the Governor General’s Award that year, describes, through her settler eyes, some experiences among First Nations people in BC.

Carr’s books, like her Klee Wyck persona, is not without its problems, contemporary critics have noted. In the Encyclopedia of Literature in Canada, Misao Dean notes of Carr’s earlier memoir Growing Pains: “Aggressively colonial, resentful of British condescension, the narrator retreats into her identity as Klee Wyck, ‘the laughing one,’ in order to defend herself against negative pronouncements on her appearance and manners.” Dean also writes that Carr’s books contain “habitual distortion of the facts of her life,” often departing “from strict fact to heighten the sense of her protagonist’s victimization.”

The signed note accompanying this book was sent to a Mrs. Mackie in Toronto in thanks for a yearly association membership card. “Mounting years and poor health make seeing to [art] shipping details burdensome,” Carr writes, “but I have had a one man show in the Vancouver Art Gallery for the last four successive years so you see I still work in spite of war and indifferent health.”

Leah Sandals is managing editor, online, at Canadian Art.

This post was clarified on July 3, 2017. In the original, it was unclear that the border marker for sale was entirely cast iron. It is, and others in the same series were also granite, bronze and stainless steel.