Philippe Battikha

Philippe Battikha wants to immerse us in embodied listening. He does this by drawing on a multisensory awareness of the ways we orient ourselves in the world through sound and its attendant frequencies of timbre, colour and physicality. Trained as a professional trumpet player, Battikha expands his curiosities around sound and space, often ensemble: he co-runs the independent experimental music label Samizdat Records, co-founded a Montreal space for improvised music, L’Envers (with Ellwood Epps and others), and is involved in the artist-run space Sanctuary of Hope (with Matthew Gagnon Blair), located in an abandoned church in Queens, New York. After completing an MFA at Concordia University in 2019, Battikha is now focused on sonic sculptural works involving obsolete objects and interactive public scenarios. “Why only look when you can also smell and hear?” he asks. “We’re never just looking…so why not be in tune with and attentive to these other elements when creating work?” In Portraits (2019), four Victorian- style oval frames are retrofitted into a concave space within the gallery wall, providing inward-peering listeners with motion-activated aural portraits. For Halo (2017), a vintage salon dryer chair is fitted with a quadraphonic sound system, inviting audiences to envelop themselves in a live feed of nearby places via an Ambisonic microphone. Currently an artist-in-residence at Darling Foundry, Battikha is planning, among other things, Foundry Laundry, a resuscitated storage room/community space to explore how aesthetics can prompt civic engagement, social reciprocity, friendship and change.

Julian Hou, Body truce (detail), 2019. Acetone transfer print on silk and cotton patchwork robe, 1.27m x 109 cm. Courtesy Cassandra Cassandra.

Julian Hou, Body truce (detail), 2019. Acetone transfer print on silk and cotton patchwork robe, 1.27m x 109 cm. Courtesy Cassandra Cassandra.

Julian Hou

Divination, the occult and hypnagogia are just a few of the varied methodologies that Julian Hou collages into a practice of environments: textiles, sound, writing, installation, furniture and performance. Hou creates other sensorial modes that elude language. He accesses these by following the explosion of narrative into form, “holding together discontinuities, discovering the relationships between them and bridging them, while thinking through considerations such as site, context, politics, history and personal references.” The resulting works impart the sensations of gliding through the time-space of the internet’s collective subconscious, or a psilocybin trip. Dreamweed (2018) transposes different motifs—the vascular bamboo plant, mechanical building systems—into scroll-like wallpaper designs, backyard vegetable-dyed textiles and T-shirts, sculptures and sonic interludes exploring associative interrelations. It holds the abstract synthesis of architectural, environmental and musical patterns, diasporic childhood memories, divination and smartphone similitudes, and bamboo’s rhizomatic structures of sturdy exteriors and flexible interiors. For “Solitaire,” an exhibition with Anne Bourse at Toronto’s Cassandra Cassandra in 2019, Hou presented Body truce, a patchwork performance robe imprinted with a text he based on Thoth Tarot card readings. It was intended to be part of an ongoing play called Cloudcuckooville, made in collaboration with artist Tiziana La Melia, but is now part of the spinoff artwork Grass Drama. Set in a font described as “medieval suburban occultic” and accompanied by a soundscape, a series of wallpapers and a folded handmade quilt, the robe’s text reads like oracle truths: “To find success in order to face death without the pollution of life…when the gate is touched they become two: the rider and the one being rode.”

Sandra Volny, Where does sound go where does it come from (still), 2016. HD video and

3D stereo sound, 8 min 47 sec. Photo: Simon Bélair.

Sandra Volny, Where does sound go where does it come from (still), 2016. HD video and

3D stereo sound, 8 min 47 sec. Photo: Simon Bélair.

Sandra Volny

Sandra Volny awakens an intra-sensorial awareness of how we are connected to all phenomena through imperceptible vibrations. Fascinated with aural spaces and inner and outer experiences, Volny conveys ambiance through videos, installations, experiments and collective interdisciplinary fieldwork, accessing deep emotional, liminal thresholds through such frequencies. “These spaces are metaphors and vectors for memory and identity,” she explains, where embodied knowing arises. “I think it is important to connect, feel and experience what is surrounding us: the invisible, the unseen and what cannot have a voice.” After completing her doctoral thesis, “The Surviving Aural Spaces,” she explored human echolocation—the ability to sense space through sound—with videos. In Sonar (2011), she sensitively documents the Hartings, a family of three blind buskers often found performing in Montreal’s Mont-Royal metro station. They know space through touch and sound, vividly describing their home and each other; their melodies locate the station’s corners and curves the same way. For Where does sound go where does it come from (2016), which emerged from the Triangular Project collective, Volny interviewed Chilean fishers as they listened to the recorded sea on headphones and identified exact coastline locations from only the white noise of crashing waves. (Unable to afford GPS technologies, they relied purely on years of sensorial perception to orient themselves.) Through her Sound and Space Research platform—an international, interdisciplinary group focusing on environmental resonances—Volny is collaborating with geophysicists and microbiologists, listening to soilscapes as witnesses to climate change. “We tend to forget that we are a part of nature and that nature is in us…. Climate change is not something outside of us. Global warming is happening in us.”

HomeShop, Beiertiao Leaks 《北二条小报》, 2010–12. Screenprinted publication. Photo: Elaine W. Ho.

HomeShop, Beiertiao Leaks 《北二条小报》, 2010–12. Screenprinted publication. Photo: Elaine W. Ho.

Michael Eddy

Michael Eddy’s expansive practice as an artist, writer and social instigator has a mischievously subversive, conceptual and Fluxus bent. A voracious collaborator who indulges in politics, psychoanalysis, humour and the collision of cultural edges, Eddy works across disciplines and media, including drawing, installation and performance. After studying at NSCAD University, he lived abroad for more than a decade, in Germany, Japan and China, where he became involved in HomeShop, a storefront residence and collective artist initiative within a Beijing hutong 互通 that experimented with the possibilities of life and art at a time of rampant urbanization. His interests in print media from treating publications as performative and as institutional critique, to testing the malleability of truth and fiction in his collaborative newspaper projects Beiertiao Leaks, YellowSide Daily and Greenbox Leaks—can be traced from here. For his 2020 Darling Foundry exhibition “Je suis” (its title referencing the solidarity slogan following the Charlie Hebdo killings in 2015), Eddy tackles identity politics and self-expression (and its sometimes disturbing alt right mutations), as well as freedom of expression, in ambiguous provocations described as “a self-critical narrative space simulating the precarious zone of universalism.” Large-scale Styrofoam engravings printed on Tyvek paper adopt the tropes of free speech and modern values in a liberal and supposedly “secular” post-Enlightenment West, testing our tolerance for lampooning in discordant times. Humanoid sculptures made from discarded leather couches challenge the idea of “armchair participation” both in art and online. Meanwhile, three videos expose the absurdities of capitalism, humanity’s penchant for pleasure in pain and the autobiographical, familial connections that underlie Eddy’s questioning of whether art and representation can broach today’s political, racial and economic divides.

Liliona Quarmyne and Mo Drescher (with Carmel Farahbakhsh), Moves & Marks: tenderness risk-boundaries, 2019. Performance. Courtesy Khyber Centre for the Arts. Photo: Heather Rappard.

Liliona Quarmyne and Mo Drescher (with Carmel Farahbakhsh), Moves & Marks: tenderness risk-boundaries, 2019. Performance. Courtesy Khyber Centre for the Arts. Photo: Heather Rappard.

Liliona Quarmyne and Mo Drescher

“Moving with each other and against one another, how do we navigate boundaries, risk, consent and space?… How can we explore our responses and reactivity to ourselves and each other in a way that is gentle and generative and also allows us to stretch beyond our current habits and comfort zones?” These are the questions and sensitivities of our time, posed by Liliona Quarmyne and Mo Drescher for Moves & Marks: tenderness-risk-boundaries, a two-week residency and “unperformance” last December at the Khyber Centre for the Arts. Quarmyne, trained in choreography, dance, performance and community organizing and facilitation—notably with Diane Roberts’s Arrivals Legacy Project—approaches the body as a link to past and future generations, exploring the role of performance in creating social change. Drescher, founder of graphic design facilitators Brave Space, is active in community organizing, having studied leadership development and systems change through the ALIA Institute. Together, they delved into a process termed “sneaky deep”— a kind of somatic movement and play that generates profound behavioural re-patterning— testing their own relationship thresholds as experimentation for broader social change. Inspired by the work of Kelsey Blackwell and adrienne maree brown, who work intersectionally with spiritual practice, social justice and creative expression, they asked: “How to stay in risk—just enough so it’s growth, but not so much that we cannot hold each other? If we hurt each other, how will our ‘container’ be strong enough to bear what we are going through?” The resulting “pleasure collage” of Moves & Marks—rosy light, music, textured fabric and reams of paper, Carmel Farahbakhsh on improvised violin and poetry by Kai Cheng Thom—created a space to explore intimacy, racial difference and radical love as political interventions: “We were wilding it enough to create a liminal space for possibilities—like a portal between this world and an as-yet-undiscovered next.

Deborah Edmeades, Quintessence (detail), 2020. Steel, aluminum, copper, quartz crystal, polyester resin, recycled fabric and polystyrene, 92 x 61 cm (approx.). Photo: Site Photography.

Deborah Edmeades, Quintessence (detail), 2020. Steel, aluminum, copper, quartz crystal, polyester resin, recycled fabric and polystyrene, 92 x 61 cm (approx.). Photo: Site Photography.

Deborah Edmeades

Phenomenology, perception and consciousness are the vast philosophical grounds for Deborah Edmeades’s artistic and therapeutic experiments. Her intermedia practice, traversing a relational circuitry of drawings, performance, video, prop objects and writing, is grounded in feeling, sensation and questions of subjective experience: How do we know things to be “true,” and why? What is the relationship of belief to desire, to free will? Her video On the Validity of Illusion (and its attractions) (2014) follows an artist-doppelgänger observing an online spiritual teacher (both played by Edmeades) who runs a series of aesthetic tests. These include the presentation of multicoloured textures and objects viewed through reflective surfaces, a “rubber hand” experiment (wherein the patient, observing a paintbrush stroking a prosthetic supplanted as her own, begins to identify with the sensations) and objects coming alive—all of which reorient our perception, proprioception and empathy. Currently, Edmeades is focused on the histories of women’s struggles for spiritual authority through feminism and contemporary New Age religion, and on the irrational beliefs that have been repressed by a supposedly rational Western mindset. As part of “Leaning Out of Windows,” a group exhibition of artists collaborating with physicists at TRIUMF, the University of British Columbia’s particle accelerator centre, Edmeades is making orgonite, a combination of found-metal shavings and resin. Orgonite has a cult following online for its DIY promise of agency in “undermining tyranny” through the rebalancing of orgon—cosmic life energy, similar to qi or prana—amid human disruptions such as electromagnetic frequencies and the climate crisis. In her latest piece, Quintessence (2020), a pink-tinted orgonite dodecahedron (the fifth Platonic solid representing aether or spirit) evokes the dark energy of our expanding universe and its endless unknowns.

Olivia Whetung, Stand (detail). 2019. 11/0 Miyuki seed beads, nylon thread, wood veneer, flagging tape and river stone. Dimensions variable. Courtesy Contemporary Art Gallery. Photo: Site Photography.

Olivia Whetung, Stand (detail). 2019. 11/0 Miyuki seed beads, nylon thread, wood veneer, flagging tape and river stone. Dimensions variable. Courtesy Contemporary Art Gallery. Photo: Site Photography.

Olivia Whetung

Olivia Whetung engages beadwork as a mnemonic device, to index memory and expose historical absences while expanding the medium’s conceptual possibilities. She dissolves craft-art hierarchies to assert that the labour, hands and bodies of these often gendered and racialized traditions be recognized and honoured in their own right. Living in the Kawarthas, on Chemong Lake, Ontario, shapes her practice: “I spend a lot of time observing, gardening and working within it,” she describes, laughing while recounting morning walks and the joyful immersion of interspecies life. “Since returning [home] I’ve witnessed the eco-destruction—how impactful the changes in weather have been to everything.” Her mother taught her beading and loomwork since childhood; her grandparents founded the Whetung Ojibwa Centre, a vibrant industry engaging local makers, and she grew up surrounded by its magic. For “Sugarbush Shrapnel,” her solo exhibition at Vancouver’s Contemporary Art Gallery, Whetung interwove concerns for local ecosystems by infusing delicate materials with labour and affection. Five scrolls of industrial wood veneer hung throughout the room, bead-embroidered and with pyrographed images depicting animal-plant symbiosis and our food systems’ interconnectedness: hummingbirds pollinating honeysuckles, a squirrel scratching the nourishing bark of a maple tree, itself being tapped by humans for syrup below. In a nearby vitrine sat Sugarbush Shrapnel (2019)—heat-exploded stone fragments from her family’s annual sap boiling, now enclosed in beaded, polyhedral time capsules. As premonitions of our current environmental instability, they anticipate a time when seasonal unpredictability threatens maple- syruping practices. On denials and deception, from colonialism and environmental degradation to other historical erasures now exposed, Whetung feels there are no objective truths: “I grew up with non-dominant narratives about the world I live in…so I never placed faith or trust in sources of authority. We could be living in post-objectivity—that makes more sense.”

Emily Neufeld, Prairie Invasions: A Lullaby, 2020. Photographic wall, 2.4 x 3.2 m.

Emily Neufeld, Prairie Invasions: A Lullaby, 2020. Photographic wall, 2.4 x 3.2 m.

Emily Neufeld

What psychic histories accumulate within abandoned, forgotten structures? How can human and other-than-human traces be salvaged amid demolition and deconstruction? Once all things decompose, what will be remembered, and by whom? Emily Neufeld investigates these questions through sculptural interventions, which she photographs and then leaves to be destroyed, within houses slated for demolition. From Vancouver homes to deserted farmhouses across the Canadian Prairies, all are casualties of a rampant capitalism. She describes each intervention as “a funerary rite, a final celebration of the indescribable synthesis between people and the places they occupied.” Poetic and empathic, the resulting large-scale photographs contemplate how humans shape, and are shaped by, our domestic environments. Cutout swaths of worn carpet create archipelagos in one house; layers of drywall are abstractly removed to exhume what’s beneath in another. Neufeld’s other human-scale sculptures, which survive the demolitions, combine material remnants found onsite with soil, plants, concrete and resin, shifting from memory’s excavation to embodied propositions on the sympoiesis of humans and nature. Deepening her consideration and respect for the Indigenous lands on which settlers, including herself, live, Neufeld recently travelled home to Alberta to visit abandoned farmhouses. She looked to nature’s metaphors for insight: the barn swallows’ empty nests, due to their decline, contrasted with the resilience of indigenous Prairie grasses and black-eyed Susans. She also observed the human desire to freeze time, sanitize, demarcate and control space, despite the fact that we all humbly return to dirt one day—all reflections that will manifest in the solo exhibition “Prairie Invasions: A Lullaby” at Richmond Art Gallery in summer 2020.

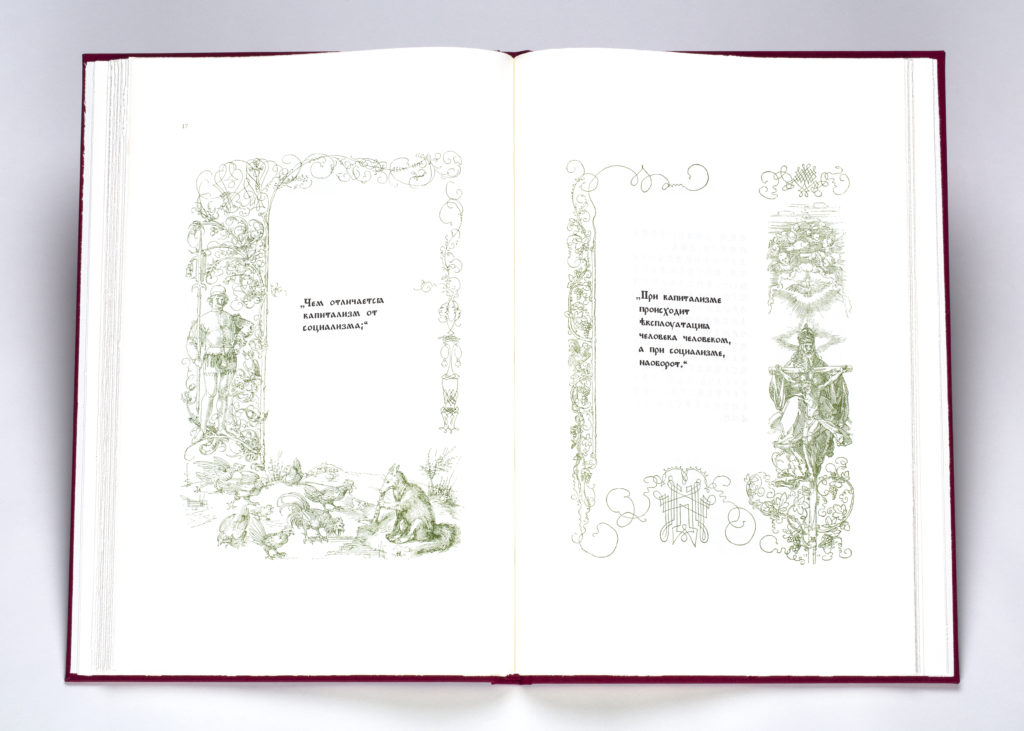

Hyung-Min Yoon, The Book of Jests #17 (Q: What is the difference between capitalism and socialism? A: In a capitalist society man exploits man; in a socialist one, it’s the other way around.), 2014. Ink-jet print, 50.8 x 71 cm.

Hyung-Min Yoon, The Book of Jests #17 (Q: What is the difference between capitalism and socialism? A: In a capitalist society man exploits man; in a socialist one, it’s the other way around.), 2014. Ink-jet print, 50.8 x 71 cm.

Hyung-Min Yoon

Hyung-Min Yoon is a conceptual artist fascinated with language, the space of translation and the construction of meaning. Through print, video, photography, installation and outdoor works, Yoon reveals the ambiguities and complexities of interpretation alongside the role technology plays in spreading ideologies across time. Ancient and contemporary materials from different cultures are juxtaposed to discordant effect, awakening the roots and legacies of language’s aesthetic and symbolic power. For Yoon, “the pleasure is in the research—of adding layers, like onions.. [and] when I’m frustrated about politics, I make books.” The Book of Jests (2014), an oversized letterpress volume, combines Albrecht Dürer’s Marginal Drawings for the Prayer Book of Emperor Maximilian I (1515) with political humour in 15 languages. Many are Cold War jokes, chosen for their contemporary and universal resonance. Dürer’s German Renaissance–style frames lend the content a classic “authority.” Yoon’s black-and-silver-lettered publication-turned installation, Black Book (2018), tackles technological determinism and patriarchy by pairing contemporary black humour and comic interspersions with woodblock illustrations from the 15th-century Confucian text “Virtuous Women,” part of the Illustrated Conduct of the Three Bonds (a Chinese volume widely disseminated in Korea through much of the Joseon Dynasty, which spanned the 14th to 19th centuries). Her tongue-in-cheek layers dredge up centuries of calcified patriarchal discipline, ideological imperialism and obedience through implied violence to preserve the social order, while touching on contemporary issues such as war, climate crisis and sexism. Its feminist force is matched only by the jokes’ satirical relief, which, in dark and divisive times, humanity has often sought out to liberate unspoken truths.

Émilie Monnet, Her Name was Marguerite Duplessis: A Silenced Story of Slavery, 2015. Performance. Photo: Scott Benesiinaabandan.

Émilie Monnet, Her Name was Marguerite Duplessis: A Silenced Story of Slavery, 2015. Performance. Photo: Scott Benesiinaabandan.

Émilie Monnet

Émilie Monnet restores collective memories silenced by colonial amnesia, amplifying them into experiences of sound, colour, texture and movement. Her interdisciplinary, intercultural practice honours long-term collaborative processes, strong matrilineal roots and Indigenous knowledge, delving into their connections to the land in times of urgent need. She has worked with Indigenous women’s groups in South America and at the Quebec Native Women’s Association with past president and Mohawk activist Ellen Gabriel/Katsi’tsakwas (the appointed spokesperson during the 1990 Siege of Kanehsatà:ke and Kahnawake). Monnet, founder of the performance platforms Onishka Productions and Indigenous Contemporary Scene, draws from training in media arts and theatre, and from her master’s degree in peacebuilding and conflict resolution to empower communities to tell stories of identity, memory and language. NigamOnTunai (2014–), titled after the Anishinaabemowin and Inga words for “song,” is a collaboration with Inga sound artist Waira Nina. In response to violence against women and continued natural-resource exploitation throughout the Americas, they draw from their respective cultures and contrasting Algonquin and Amazon climates to create performances infusing sound, movement, water and light projections. Such immersive environments create what Monnet describes as “a different universe—a different way of listening, of receiving” and, as Nina says, of “captur[ing] an invisible world.” Synaesthetic feelings coalesce before language does, as Nina resounds a snake-like gramophone and Monnet dances against cellular crimson light. Monnet’s next project connects the story of Marguerite Duplessis—an enslaved Pawnee woman who challenged the judicial apparatus of New France in 1740 by requesting freedom before being deported to the West Indies to our present-day “justice” system’s failure to protect cultures other than those of white patriarchy. Monnet is intent on showing a history of women’s resilience and allyship between cultures, despite forces that attempt to divide and forget. “The focus is to bring these occulted stories to the surface,” she explains, “also revealing a long history of not caring.”

This story was updated on April 22, 2020, to reflect that Julian Hou’s practice uses Thoth Tarot cards, not Thor Tarot cards, and to clarify details of the play Cloudcuckooville. It was also corrected to clarify that Philippe Battikha is involved in, but not a co-founder of, the artist-run space Sanctuary of Hope.