Gliding back and forth in a rocking chair

Demands for justice rising in symphony with my baby’s breath

I watched from home

Tears running down my cheeks

Bringing out the curls in her hair.

I quickly typed these words into my phone after watching the streets rise in flames following the murder of brother George Floyd. I was at home, holding my sleeping baby brown girl in my arms, and feeling a familiar call to action more intensely after hearing one of his last words, “Mama.”

I was holding my girl again when the request to write this piece came through. I was asked to consider “protest” and art, specifically in the Black Lives Matter and Land Back movements. I’ve been thinking about protest for a long time. What does it mean to protest? Does it mean something different when the act of simply living and moving on your homelands pushes you into the confines of the category labelled “protester”?

I am Inniniwak and Trinidadian—an Afro-Indigenous woman and a new mother living, creating and actively contributing to work that builds a world worthy of my daughter, a world for her and other children who are the continuation of lineages that survived multiple waves of genocide and assimilation, and the twin thefts of Land from People and People from Land.

I gave birth to my daughter, Isabella Kiizhigooweyabik, after 36 hours of hard labour. With the last push and release of every ounce of strength I had left, she shot into this physical world and took her first breath. Soon after, she let out the most beautiful sound I have ever heard: her first cry, both announcing herself to Creation and offering her original protest song, a song that joyfully rose above any force that attempted to steal life from those who came before her.

Her birth, my own personal resistance movement, is inextricably and intimately tied to movements like Black Lives Matter and Land Back.

From her time spent with the Ancestors, my daughter brought with her the teaching that protest is not always the fight against something.

Protest is in the sweat on the brow of a person bringing forward new life.

Protest is in the laughter of families healing together.

Protest is in the words of languages being spoken after a long slumber.

Protest is in dancing feet, pounding like heartbeats on the Land in ceremony lodges.

Protest is in the mouths that etched beauty on birchbark, and in the hands that bead stories on smoke-tanned hide.

Protest is in the breath you’re breathing as you read these words.

I share this not to take anything away from movements like Black Lives Matter, Land Back and the many other movements that came before them to keep breath in our bodies—which have flowed like rivers through the streets and over our homelands—but to hold space for those who can’t be on what’s often seen as the frontlines and to contribute to the pursuit of liberation in different ways and from other places.

Having had my entrance into motherhood coincide with a global pandemic, it hasn’t been possible for me to physically stand with the thousands of Relatives who have stepped forward in defence of the lives of Black and Indigenous Kin, and the well-being of the Land and more-than-human world. I have felt guilt, and I have grieved at not being able to participate in important actions and organizing. These feelings remind me of the possibilities that emerge when we understand resistance as more than a response to oppression, and instead as something that centres our own wellness, love, beauty and brilliance. This is necessary, because we deserve to experience all the good in the world.

My friend and mentor Leanne Betasamosake Simpson shared a teaching with me one afternoon while visiting in my home territory of Northern Manitoba. The teaching tells of a time when there was a breakdown between the Anishinaabeg and the Hoof Nation, a relationship originally premised on mutual respect, reciprocity and interdependence. In the teaching, the Anishinaabeg are forced into keeping themselves accountable for not upholding their sacred agreements with the Hoof Nation, whose citizens—the deer, moose, elk, caribou and other hooved Relatives—refuse ties with the Anishinaabeg because of the harms they suffered in the relationship breakdown.

The teachings, of the right to refuse harmful relationships and the agency to redirect any energies from those relationships back into ourselves, are embedded in a beautiful story, one far longer and more expansive than that which I’ve shared so briefly here, and are so important for the time we are in now.

Black and Indigenous people have been reaching for life in all ways, always. We are here continuing the fight for freedom that our Ancestors lovingly moved forward with us on their minds and hearts. It is that same love—one that is so powerful it can make you imagine whole new worlds for people whose faces your eyes have yet to rest upon—that brings us to this time.

When we understand protest as an act of love, it is easy to see it as both a responsibility and a privilege. We live today because the love of the people who came before us was fierce and unwavering. My mother has always reminded me that the movement didn’t start with us, and it won’t end with us, but is ours to carry for the moment we are in.

For now, I watch the “protests” through the screen of my phone, but I see so much more than what that word can hold. I see people stepping forward into the legacy of loving resistance handed to them by the Old Ones.

I extend my gratitude to them,

and to the others, like me, who are home bringing up the next wave, I extend these words:

Parenting in a time of protest doesn’t mean you’re sitting on the sidelines.

The revolution wakes you before the sun comes up.

It asks you a million questions a day.

The revolution wants kisses for where it hurts and extra cuddles at bedtime.

You breastfeed the revolution,

tell it stories and sing it songs.

The revolution calls you Mama.

The frontlines are wherever our bodies are,

and some of our bodies are at home,

raising the revolution.

This is an article from our special all-Indigenous digital issue, “Sovereignty.”

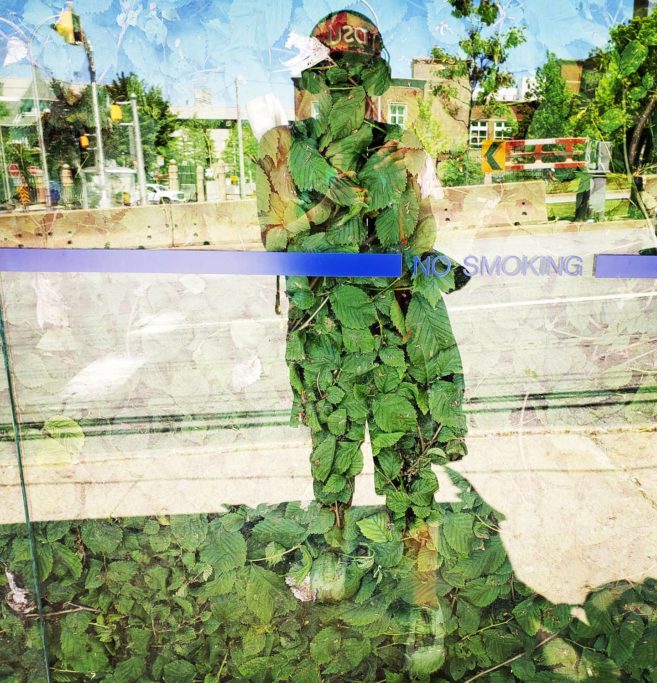

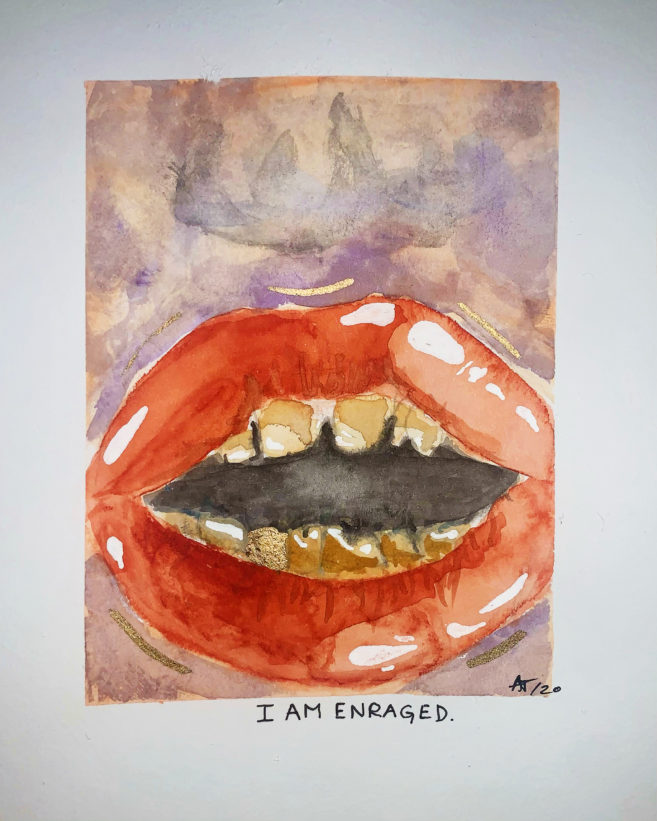

Photo: Travis Ross. Courtesy the author.

Photo: Travis Ross. Courtesy the author.