Ernest “Aness” Dominique woke up after a near-sleepless night of tossing and turning in late September. He couldn’t stop hearing echoes of the moans and screams of Joyce Echaquan. The 37-year-old Atikamekw mother of seven from Manawan, a First Nations reserve in the Lanaudière region, died moments after she livestreamed a video of a nurse and a hospital orderly taunting her with racist remarks. The incident took place on September 28, 2020, at the Centre hospitalier régional de Lanaudière, in Joliette, about an hour northeast of Montreal.

Dominique saw replays of the incident on TV from his home in Sept-Îsles. The next morning, he sat down and painted Echaquan.

“I was troubled and had many emotions,” said Dominique in his slow, Innu-aimun–inflected accent during a telephone interview in French in October. Dominique did not know Echaquan personally, but said he was affected by her death because it reminded him of the blatant racism faced regularly by Indigenous Peoples in Quebec.

“It’s very terrible [what happened to Joyce]. I cried when I saw the clip on TV,” said Dominique.

The warm and vibrant painting of Echaquan’s face captures a joyful, strong woman with a fearless look in her eyes.

Dominique, an Innu artist originally from Matimekosh, a First Nation in northern Quebec, near the Labrador border, said he painted the portrait of Echaquan—titled Justice for Joyce—in just four hours.

“I’m touched by what happened to Joyce,” said Dominique. “That’s why I made the portrait; I think it’s powerful—the look in her eyes.”

Two days before her death, Echaquan was experiencing severe stomach pain, and so travelled almost 200 kilometres south from Manawan to Joliette for medical care. During her last moments, Echaquan livestreamed from her hospital bed in a bid for help. The video shows Echaquan writhing and shouting in pain while hospital staff taunt and degrade her in French, calling her a “fucking idiot” and telling her she is “only good for sex.”

Her family reports that Echaquan suffered from a heart condition and had a pacemaker. By the 28th, her pain had worsened. Speaking in her Atikamekw language on Facebook Live, Echaquan pleaded for someone to help and to “come see me.”

Family members also said Echaquan was allergic to morphine and that hospital staff gave it to her against her will. Before the video ends, further insults from the nurse and orderly can be heard, telling Echaquan in French that she was “stupid as hell” and would be “better off dead,” before adding, “You made some bad choices, my dear. What do you think your children would think, seeing you like this?”

Echaquan died in her hospital bed shortly after recording the video.

An international outcry for justice ensued after Echaquan’s video was shown on media platforms around the world.

For Dominique, painting Echaquan was a healing experience. He said he was consumed with inspiration to paint her and couldn’t concentrate on anything else until he was done. He then shared an image of the painting on Facebook, where, after it was shared hundreds of times, Echaquan’s family saw it. Her mother, sister, husband and other relatives immediately reached out to Dominique to thank him for beautifully commemorating Echaquan. Some family members even changed their profile pictures to Dominique’s painting.

“I allowed anyone to download it [or] print it without paying me anything,” said Dominique of the image he hopes will help others struggling to make sense of her death.

Ernest "Aness" Dominique.

Ernest "Aness" Dominique.

Dominique, 55, is a self-taught artist who has exhibited across Canada, as well as in the United States, Europe and Asia. Some of his past work includes scenes of historical Indigenous figures and modern portraits of captivating faces depicted on canvas with colourful acrylic and oil paint. He currently works for First Nations in the area bringing back to life old photographs of Elders from the turn of the 20th century through his paintings.

He has addressed the MMIWG2S crisis in the past through his work.

Although at the time of our interview it had been just over two weeks since Echaquan’s death, Dominique says he’d already noticed a big change in the atmosphere of his hometown.

“She was murdered; that is bad. But the good thing is all the Native unity that’s happening. And we are talking about [racism]. And when we can see it, we can have change.”

On a recent shopping trip, he said a white store clerk took a sudden interest in him. When Dominique would normally be met with mistreatment or racism, this encounter gave him hope.

“The white [clerk’s attitude] changed. He wanted to talk. He was smiling at me. He had watched the news [about Joyce]. And he apologized for her death. It is a very powerful change.”

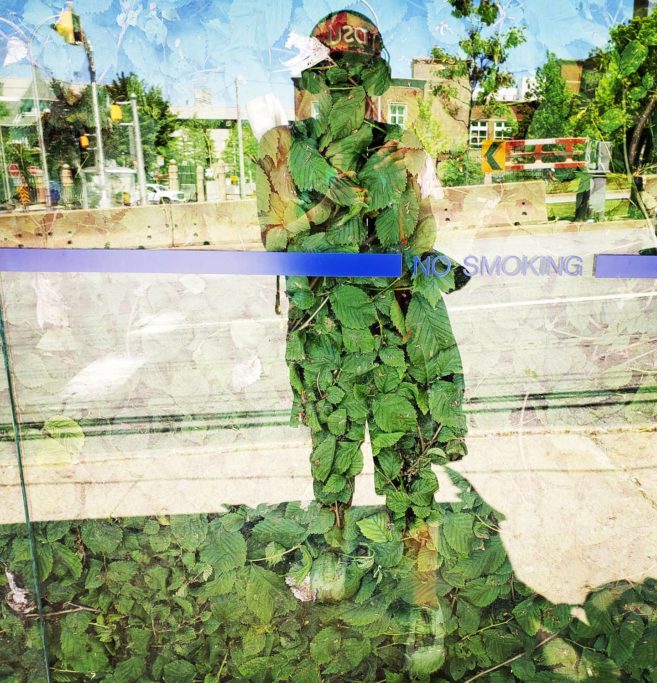

Heather Campbell, Great White North, 2019. Ink on watercolour paper, 56 x 76 cm.

Heather Campbell, Great White North, 2019. Ink on watercolour paper, 56 x 76 cm.

The MMIWG2S genocide stretches from coast to coast to coast. Head west of Quebec to Ottawa to witness an arresting work on paper created to send an unforgettable message. Bright blood-red ink drips down a Canadian flag, with the maple leaf in the centre replaced by a red parka, a reference to the Red Dress Awareness Campaign, an international initiative bringing attention to MMIWG2S. It’s an amauti—the traditional parka worn by Inuit women—with an enlarged hood for carrying babies. The red amauti drips red ink that mingles with the red in the flag. Titled The Great White North (2019), by Inuk artist Heather Campbell, the work is a provocative but honest interpretation of the MMIWG2S crisis.

“The Great White North was inspired by conversations about activism and how everyone has different ways they can advocate for change. Art is my way of speaking up,” explained Campbell in her artist statement at the 2019 unveiling of The Great White North at Montreal’s La Guilde.

“In this piece I wanted to make the connection between government policies and risk factors that contribute to violence against Indigenous women, more specifically Inuit women.”

Campbell, a single mother and Indigenous-rights advocate based in Ottawa, is rooted in her stance of the seriousness of MMIWG2S. The violence depicted in her image is needed, she said, to help people who see it to wake up.

“I wanted it to be very in-your-face, especially for the people who see the exhibition down South,” said Campbell, who is originally from Rigolet, Nunatsiavut. “I also want Inuit to see it and for it to have a direct impact on them. I want us to be forced to look at it and not ignore it.”

Black splotches appear in the background of the painting, which represent MMIWG2S, she added.

Creating the piece was an intense experience, she said. There was anger, sadness and many other feelings she was unable to put into words.

“It’s easy to be desensitized to this,” she said. “But there’s something there [that is] so immediate. A gut reaction, you can’t ignore it. And you create through art.”

Campbell has taken her nine-year-old daughter to protests for MMIWG2S awareness and does her best to navigate explaining to her the harsh realities of the dangers to Indigenous women and girls. She believes art is a straightforward way to express the threat.

“It can be tough sometimes, but I don’t shy away from letting her know. I more so teach her about the political aspects and not the physical violence.”

This isn’t the first time Campbell has showcased her talent to garner attention about violence against Indigenous women. Her 2017 work Methylmercury depicts Sedna, an Inuit sea goddess and symbol of Inuit women, being choked by a phallic-shaped cloud of black poison. It features skeletons with red eyes, maggots and other sinister imagery. The piece is meant to be shocking, she said.

“Yes, the image is violent. It looks like the poison is being shoved down her throat. It represents the destruction of the Land and what’s being done to Indigenous women.”

She created the painting during the construction of the controversial Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project in Labrador, which is now causing mercury and other heavy metals to leach into the water and affect the surrounding ecosystems. She believes the destruction of Indigenous lands correlates to violence against Indigenous women.

Heather Campbell, Methylmercury, 2017. Ink on mineral paper, 71 x 51 cm.

Heather Campbell, Methylmercury, 2017. Ink on mineral paper, 71 x 51 cm.

“When that happened, [I had] a disgusted feeling. A feeling of violation that the company was going to do that to our land and water. There’s such a connection to a woman being violated,” she explained, and it’s time people understand it.

More than 4,000 kilometres to the northwest of Ottawa is a striking mural on the outside of a Staples store in Whitehorse. It depicts a mother and daughter with dark hair; pink-and-blue clouds envelope them as a mystifying grey wolf watches over them.

Although the women are smiling, with gleams of light in their eyes, it’s an imagined light of the better place they’re in now. How they left his world is distressing.

The mural’s subjects are Angel Carlick and her mother, Wendy Carlick, of the Kaska Dena First Nation. Both are victims of violence against Indigenous women: they were killed in separate incidents, 10 years apart.

The stark portrayal is a devastating example of the rampant violence Indigenous women face, viewing mother and daughter both lost to the MMIWG2S crisis.

Angel was a 19-year-old woman who was about to graduate after completing her high-school diploma. She was active in the Youth of Today Society in Whitehorse, running the dinner program there. She also helped to paint several murals across town with Lancelot Burton. For Burton, the prominent mural is a haunting reminder of Angel and her love of painting.

“[Angel] was lots of fun,” said Burton, who helped paint the mural of Angel and Wendy. “She was always laughing, joking around.”

According to authorities, Angel was last seen in late May 2007. Her decomposed body wasn’t found until almost six months later, in a shallow grave outside of Whitehorse. Her killer has never been found, and local RCMP are still investigating.

Her heartbroken mother, Wendy, who raised Angel and her brother, Alex, as a single parent, then became a well-known advocate for MMIWG2S. Tragically, Wendy was scheduled to meet with officials for a MMIWG2S pre-inquiry hearing in Whitehorse days before she was found dead. Yukon RCMP state Wendy died alongside her friend Sarah MacIntosh at MacIntosh’s home on or around April 10, 2017, in what they determined to be a double homicide.

Just three months after Wendy’s murder, Burton led a team of local painters from the Youth of Today Society to honour the mother and daughter in the mural.

“It was very emotional. We are all connected around here. There were friends, family members of theirs—even Elders joined in to paint,” said Burton. “It’s healing, and it’s a beautiful depiction of them. We don’t see too many people honoured in death like this. So, if people don’t know about this issue, it’s very visual. A lot of times paintings don’t depict real situations like this, but this, it’s real.”

In late May 2018, RCMP charged Everett Chief, then 44, originally from Watson Lake, Yukon, with one count of first-degree murder in Wendy’s death and one count of second-degree murder in MacIntosh’s death. At the time of writing, no date for his trial has been announced.

This is an article from our special all-Indigenous digital issue, “Sovereignty.”

Ernest "Aness" Dominique, Justice for Joyce, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 61 x 51 cm.

Ernest "Aness" Dominique, Justice for Joyce, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 61 x 51 cm.