How do you ask for a reference letter to an MFA program when all the people who taught you in art school have left for better jobs elsewhere? How do you access mentorship in an art college when your instructors are busy commuting between jobs at three different schools in the same semester? And how do you ask a professor for help with a vulnerable project when they share an open office with dozens of other teachers?

These are some of the questions that students at Canada’s largest art schools are facing as precarious contract-labour conditions continue to dominate the sector.

As a Canadian Association of University Teachers study indicated this week, many instructors are suffering under this practice too, with two-thirds of CAUT study respondents saying “their mental health has been negatively impacted by the contingent nature of their employment.” As Mathew Reichertz, president of the Faculty Union of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, attests in an email: “I worked as a part-time instructor for six years before getting a full-time position….I also remember the anxiety every four months about whether I would have work the following semester. Finances were complicated because, without a teaching contract my income dropped significantly but, because I had other part-time jobs, Employment Insurance was not really an option. This is a systemic problem that doesn’t exist only in post-secondary education: many people cobble together a living with more than one job. It is a societal problem that places profits, flexibility for the employer and the ‘sustainability of institutions’ above the basic needs of individuals.”

According to faculty associations and related research, the numbers are as follows: OCAD University has the highest ratio of contract and sessional faculty in Ontario, with temporary instructors representing more than 65 per cent of the university’s faculty. At Alberta College of Art and Design, a little more than 50 per cent of courses have been taught by contract workers this school year. At Emily Carr University of Art and Design, 56 per cent of all undergraduate course sections in 2016–17 were taught by non-regular faculty (mainly comprising sessionals and lecturers). And at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in summer, fall and winter of 2017–18, approximately 55 per cent of courses were taught by contract academic staff (CAS).

“There is a phrase I like to use in meetings: Without contract academic labour, the institution would fail,” says Mark Giles, sessional rep for the ACAD Faculty Association. “I’m not saying it would just struggle. If we weren’t teaching half the courses, there wouldn’t be an institution.” Yet, he notes, when times are tough, contract staff are often the first to be let go, and often without notice or severance.

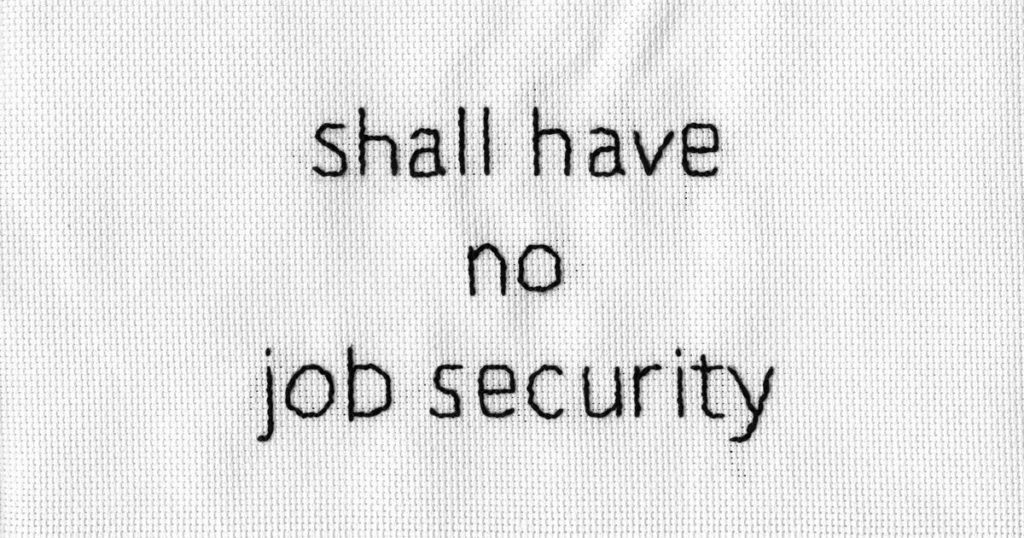

A photo of 9.03.3, 9.03.5, 9.03.7 (2018) by F. Braun, a former ECUAD sessional instructor. They made this cross-stitch in response to the fact that the ECU Collective Agreement uses this phrase three times in reference to non-regular instructors. Photo: Facebook/Non-Regular: a book about precarious academic labour.

A photo of 9.03.3, 9.03.5, 9.03.7 (2018) by F. Braun, a former ECUAD sessional instructor. They made this cross-stitch in response to the fact that the ECU Collective Agreement uses this phrase three times in reference to non-regular instructors. Photo: Facebook/Non-Regular: a book about precarious academic labour.

“We say working conditions equal learning conditions,” Charles Reeve, president of the Ontario College of Art and Design Faculty Association, notes. With sessional teaching predominant, Reeve says, “It becomes very difficult for students to establish long-term mentoring relationships…. A student might come to me and say, ‘Can you write a letter of reference for grad school?’ I say, ‘Well I can, but we’ve only had one class together a few years ago…you need someone who can write you a letter having had you in a couple of courses. And the student says, ‘Well yeah, I would love to, but they’re all gone. They were sessionals.’”

Vancouver artist Terra Poirier, who is a 2018 ECUAD grad, is so concerned about the impact of precarious labour on art education in Canada that she has edited a book about it in collaboration with 26 artists and teachers—many of them quoted anonymously or pseudonymously. The book, titled Non-Regular: Precarious Academic Labour at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, launches October 23 at the university during Fair Employment Week and Vancouver Art Book Week.

“Last-minute hiring of instructors means that students often have to register for courses without knowing the instructor or even the topic,” Poirier explains in an email. “My instructors often do not know me and certainly cannot give me feedback on how my work has developed over time. Because most of my instructors (most of them have been sessionals) do not get paid to do service and have to hustle to the next gig, I often don’t have access to them once our class is finished. That means that I can’t ask them…for advice that I genuinely need as I develop my professional practice.”

As someone who experienced poverty and precarity herself, and who returned to art school as a mature student, Poirier was especially surprised by the conditions most of her art college instructors live with: “I am concerned that the majority of my instructors are being under-compensated for their work. For many, this can mean living near or below the poverty line,” Poirier writes in an email. She adds: “What does it mean when the biggest lesson we take from our education is that there’s no future in learning?”

“How can an art school justify undervaluing artists in this way? Or, for that matter, how can any place of learning defend undervaluing educators, i.e., learning?”

This week’s Canadian Association of University Teachers study notes that the negatives of contract work affect some people more than others. “Women and racialized contract academic staff work more hours per course, per week than their colleagues and are more likely to be in low-income households,” says a CAUT release.

And even when sessionals are consistently well-paid, they can suffer in other ways. “Something particular about ACAD was that it was basically run by sessionals for many years—there was just a handful of permanent people,” Mark Giles explains. While he thinks an increase of permanent faculty is a good thing at the school, there is a different problem now: Sessionals “used to have a much bigger say…in how the institution imagined itself, how it looked to programming, how it looked towards future,” says Giles. “And frankly, we no longer sit on any of the committees that make those decisions.” That loss of agency is an issue for many sessionals, he says.

At OCAD, says Charles Reeve, some sessional instructors don’t know until July or August if they are teaching in the fall. “When you sign one of these contracts it says that the contract can be cancelled without any compensation up to a week prior to the class,” says Reeve, “And furthermore, if it is cancelled in [the] week before class, you get a pretty minimal cancellation fee.”

At the same time, Reeve notes, the OCADU administration wants instructors to post course outlines three weeks in advance of class start so that students can make informed decisions and be prepared. While Reeve thinks this is a very good initiative in supporting student mental health, he notes that it requires some sessionals to start working before the actual start of their contract—a contract that might even be cancelled if enrolment is lower than the college desires.

The result of precarious employment at art schools is also mixed messages to students about the value of art and artists, says Terra Poirier. “I believe that ECUAD is literally capitalizing on the existing precarity and underemployment in the arts sector, as well as the long-held mainstream notion that fine art is not of value to society,” Poirier argues. “How can an art school justify undervaluing artists in this way? Or, for that matter, how can any place of learning defend undervaluing educators, i.e., learning?”

Local cultural ecologies can also make sessional teaching more or less viable, depending. In Vancouver, high housing prices raise the precarity stakes for ECUAD teachers, while “at NSCAD the problem can be more acute [than some other cities] because there are no other post-secondary art programs in Halifax, so even if they wanted to, our CAS couldn’t go looking for more work teaching at other institutions,” writes Mathew Reichertz.

Contract instructors at ACAD are evaluated more heavily on criteria that are less fair, Giles points out. “Student teaching evaluations are weighted more heavily for sessionals than for other faculty,” says Giles, even though a recent Ryerson University arbitration decision showed that teaching evaluations are not a useful metric of teaching effectiveness.

“Thousands of highly educated, debt-carrying professional instructors are helping to prop up our post-secondary educational system along with many more thousands of students who are taking on more and more debt in order to participate in it.”

The impacts of sessional teaching precarity in the arts also bear on what is taught in art classes—edging syllabi toward safer, less urgent material. “What I did not fully grasp prior to producing this book, but learned from my contributors, is that this lack of security is having a direct impact on academic freedom and the quality of our education,” Terra Poirier writes in an email. “This is happening on a few levels. One of them is that neoliberal employment practices at universities have positioned students as customers, which as one contributor wrote, ‘makes it difficult to build [a] challenging curriculum, because [a] challenging curriculum risks failure. And, failure could cost us our jobs.’”

Of course, the problems of precarity in sessional teaching are not particular to art schools. Mark Giles went to a contract instructors conference this summer with representatives from Canada, the US and Mexico, and says there are many issues in common there across the continent. And not every sessional instructor in Canadian art schools is upset with the status of their employment—Giles says that at ACAD, pay for sessionals is pretty good, and many artists there who have professional practices (himself, a novelist, included) appreciate having time to maintain their own creative practices.

Likewise, many other non-art universities and colleges also exploit contract and sessional staff. And government policies encourage it: “I think that it is important to acknowledge the role that government plays in this systemic problem,” Mathew Reichertz writes. “About 50 per cent of university funding comes from the government today; 20 to 30 years ago it was more like 70 per cent. The gap between historical levels of funding and present levels of funding has progressively been filled by paying low wages to CAS and by increasing tuition. Thousands of highly educated, debt-carrying professional instructors are helping to prop up our post-secondary educational system along with many more thousands of students who are taking on more and more debt in order to participate in it. The funding that goes to post-secondary education is the result of government priorities. We all have the right and the responsibility to let our representatives know what kind of [education] system we believe will be fair and effective.”

But as Poirier has pointed out, it’s possible the precarity issue is exacerbated in art schools given precarity in the arts sector as a whole. Poirier hopes that the new CAUT study, and the upcoming Fair Employment Week across Canadian universities from October 22 to 26, can be a wake-up call not only to administrators and publics, but to students.

“It’s not really a conversation that is safe for non-regular faculty to have openly, certainly not with students—it’s too easy for instructors to simply not get offered courses again,” Poirier writes. She explains, “I want my fellow art students to understand that our precarity is tied up with that of our mentors. I want us to take up these issues with administration. Historically, artists have been deeply involved in social movements—where is that energy now?”

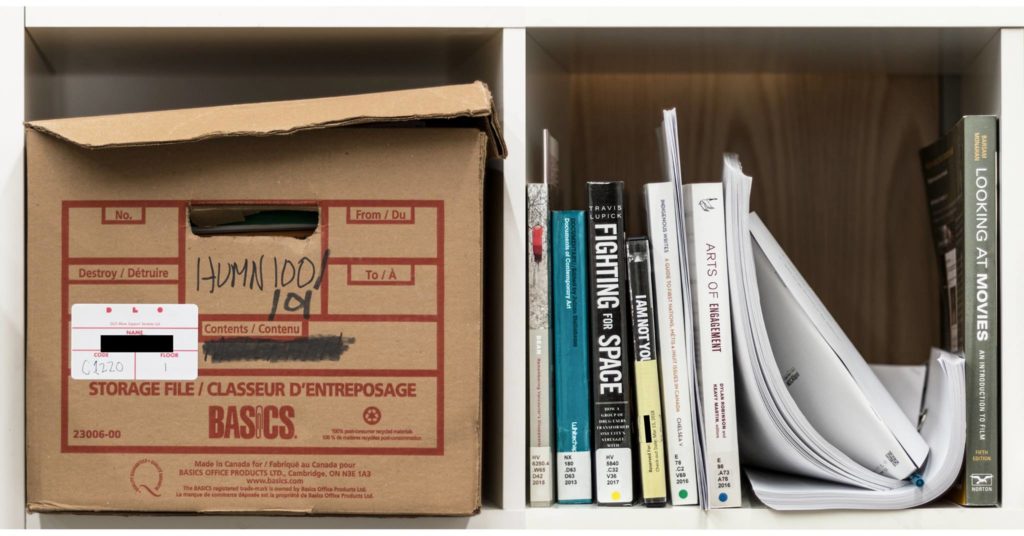

A view of storage areas for sessional instructors at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. A new book, Non-Regular, looks at conditions of contract academic staff there. Photo: Terra Poirier.

A view of storage areas for sessional instructors at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. A new book, Non-Regular, looks at conditions of contract academic staff there. Photo: Terra Poirier.