Most people who have displayed work in The Cheeky Proletariat live or work in its neighbourhood, near Vancouver’s Carrall and Cordova Streets. Having worked nearly two decades in two different organizations a block away from this particular intersection, I’ve had a close eye to changes there over the years, more so than to the eight other lower mainland neighbourhoods I have lived in during that time. Travelling on foot in the downtown eastside, heading west on Cordova past Carrall en route to the train, has remained a most familiar path. In the downtown eastside, or DTES, people who live here are made vulnerable by housing and income precarity, illness and stigma, drug-war policy, policing, violence and displacement. Formal and informal support structures in the area animate the sidewalks day and night. It is a place of historic battles for housing, harm reduction, and rights and dignity for drug users. The prevailing guidance of Indigenous women organizing in the neighbourhood through the decades has advanced anti-colonial struggle well beyond Vancouver. When a small storefront at 320 Carrall Street began to show signs of life in 2015, after years of vacancy, people noticed.

Anthonia Ogundele is the founder of The Cheeky Proletariat (“The Cheeky,” as she often refers to it) and co-owner, with her husband, of the ground-floor condo where it is housed. The eight-by-five-foot space had originally been a closet that backed on to the street. “Both of us are urban planners and saw that that particular strip [of Carrall Street] had not been activated,” explains Ogundele, “so we sealed off the closet from the unit and opened up the space to allow for more access.” Ogundele reached out to me early on in the project as a compatriot of Vancouver’s creative Black community while I was working as an arts administrator at the nearby Gallery Gachet. I now recognize that her invitation to connect manifested elements of The Cheeky’s entire mandate.

View of “Where Are You From?” opening night, February 2016, at The Cheeky Proletariat. Photo: Kirsten Roy.

View of “Where Are You From?” opening night, February 2016, at The Cheeky Proletariat. Photo: Kirsten Roy.

View of “Where Are You From?” opening night, February 2016, at The Cheeky Proletariat. Photo: Kirsten Roy.

View of “Where Are You From?” opening night, February 2016, at The Cheeky Proletariat. Photo: Kirsten Roy.

The same year The Cheeky opened, I briefly sat on a Hogan’s Alley Society subcommittee regarding the Northeast False Creek Plan, a city development proposal for replacing the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts. Hogan’s Alley was historically the centre of Vancouver’s Black community, and recent education and mobilization continue efforts to recognize and hold this space. In the early 1970s, the construction of the viaducts gave the City cause to aggressively displace, by various means, the Black community established there. As the crow flies, The Cheeky is just a few minutes away from the viaducts. The tenacity of the Hogan’s Alley Society and its subcommittee members amplifies the history and contribution of Black settlement in the city and across the Pacific Northwest. A climate of erasure and anti-Black racism persists, however, as does the need for low-barrier exhibition and artmaking spaces.

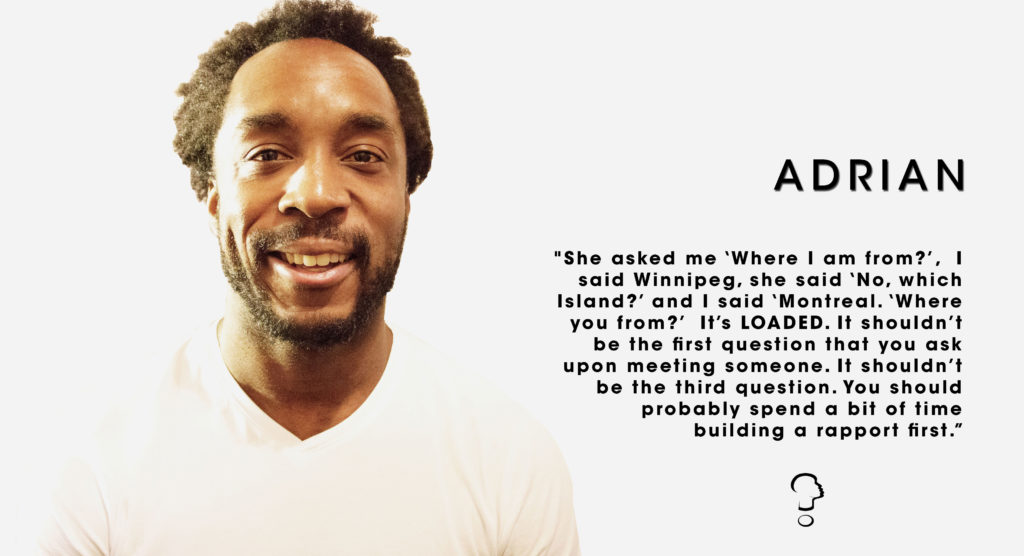

The Cheeky intends to provide an inclusive and accessible space for the free expression of all people. For example, a contributor who exhibited samples of his fashion line at The Cheeky in 2019 is also the caretaker of the building. Notes Ogundele, “You don’t have to identify as an artist.… I don’t even put ‘art’ or ‘gallery’ in the description, per se. It’s just a space where you’re able to express yourself if you have something you want to say or share.” She cites hip hop as a popular influence on how she imaged The Cheeky’s inception, specifically the capacity of visual culture to transform spaces and walls into meaningful places. Community relations are also foundational to its vitality. With Black History Month as a springboard, the space sought to “daylight Black artists, Black stories, and to empower young people to not just show their art but curate work and build capacity in community.” It gained footing and recognition with the 2016 exhibition “Where Are You From?,” an installation of portraits of 40 Black Vancouverites—also compiled into a book—alongside subjects’ narratives regarding their experiences of being asked about their origins. The photoshoot for the portraits was hosted at the beloved Caribbean restaurant Calabash Bistro, one block south of The Cheeky on Carrall Street, where a painting by the dearly missed Floyd Sinclair Sandiford, which anchored the 2016 show, is now displayed. Ogundele reminded me recently that I was surprised during the photoshoot to be in the company of so many Black people in Vancouver whom I did not know. The effort forged new relations and communications.

Shahanah Shivji, Adrian (from the series Where Are You From?), 2016. Digital image, dimensions variable.

Shahanah Shivji, Adrian (from the series Where Are You From?), 2016. Digital image, dimensions variable.

Nanyamka (Nya) Lewis, a contributing artist to The Cheeky and later its curator throughout 2018, struggled to find and connect to Black artists and community when she first moved to Vancouver from Toronto in 2016: “Being in Vancouver sent me on a spiral…based on not having communities of Black folks or Blackness, and also this very passive-aggressive type of communication. Like, you are expected to step off the sidewalk for others…. You question your own existence, you have to touch your skin and be like, ‘I’m here right? I’m standing in this body.’”

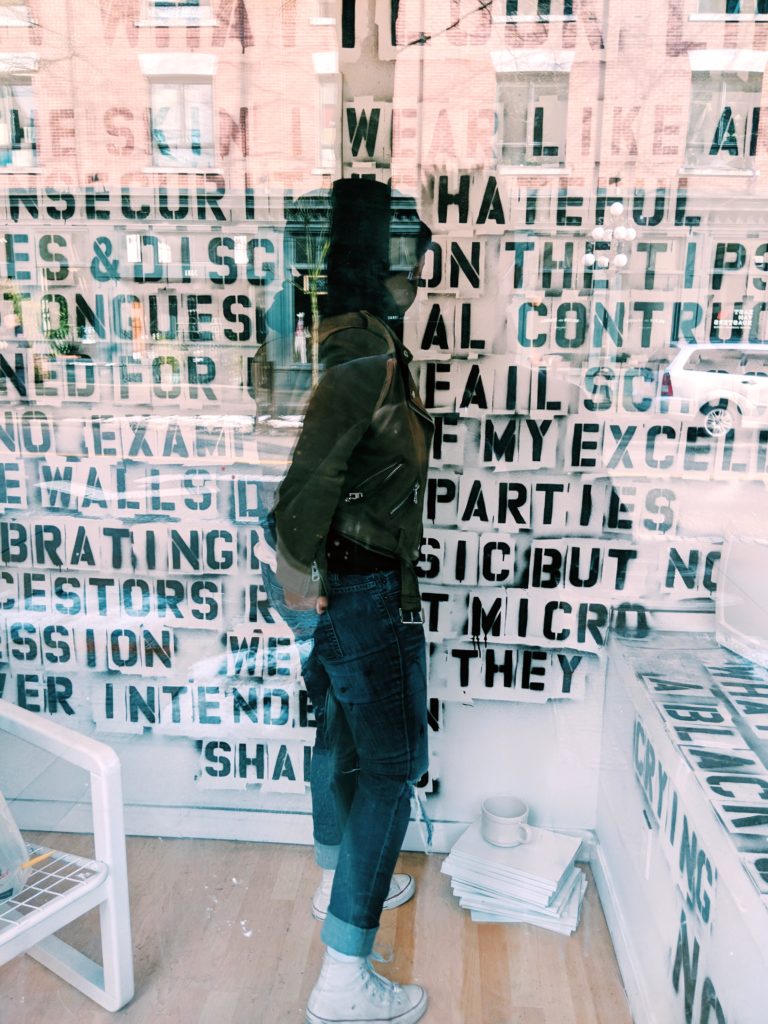

Lewis mounted her installation The Feels: Thoughts on Mental Health in the Black Community at The Cheeky in February 2018. It centred on a poem, the text for which covered nearly every inch of the walls. Lewis was grateful for the response from the Black community in Vancouver, who shared tears and stories in response to the content. She notes that “Just a couple of months before that, someone had broken into my car and spray-painted ‘nigger’ in my backseat. In talking through the exhibition there was this breakdown of [the notion that] ‘This doesn’t happen here.’ It does happen here, to me. I see, I get it. The emotional reaction was more than I could hope [for] or expect.” Lewis recalls the work being an exploration that came out of anger and grew into a bigger conversation about mental health advocacy—about what it means to hold space where Black women and girls can just be.

Nanyamka (Nya) Lewis, Not Me, 2017. Acrylic spray paint and stencil, dimensions variable. Photo: Idrissa Brathwaite.

Nanyamka (Nya) Lewis, Not Me, 2017. Acrylic spray paint and stencil, dimensions variable. Photo: Idrissa Brathwaite.

The social biases that instigated the construction of the viaducts and destroyed Hogan’s Alley also underline the planning of the Carrall Street Greenway, a sparsely treed path and bicycle lane completed by the City in 2009. It connects Chinatown, the downtown eastside and Gastown—the latter district known now for its pricey retail shops and restaurants—roughly in a six-block stretch. This area has long been a site of contestation: “crime prevention through environmental design” policies, implemented in Vancouver and elsewhere to purportedly increase civilian traffic, have informed the area’s urban planning. The real effects include the discursive and material divisions between the notions of “civilian” and “criminal” (read: criminalized), which have become more entrenched, along with increased policing, institutionalization and the continued removal of low-income, Indigenous and racialized residents of the neighbourhood. The reenactment of these precipitating conditions in artmaking risks being absorbed into the displacement and development itself. Exhibitions touching down on historic Carrall Street a block away from where The Cheeky stands, such as Althea Thauberger’s Artspeak commission Carrall Street and Stan Douglas’s photomural Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 (both 2008), which he made with real estate developer Westbank, loom as classed and ultimately disconnected performances relative to the lived experience of most residents and workers in the neighbourhood post-2010.

The Cheeky can only be engaged from the sidewalk; it fits a chair and one or two people uncomfortably inside. In his profile “‘The Cheeky Proletariat’ Is for the People,” published in the Tyee, local writer Olamide Olaniyan explains that “the gallery transforms its part of Carrall Street into a public space.” For at least one full day during the run of the show, people exhibiting there are expected to be onsite to visit with the community (many visit more often and engage in social and public installation processes), but the space is otherwise unstaffed. Cherished but small, thoughtful but loosely structured, this closet storefront provides a strong link to meaningful community for Lewis and other participants, and it’s a sobering comment on where Black women and girls may feel their art has a place in Vancouver.

Street view of The Cheeky Proletariat. Photo: Shahanah Shivji.

Street view of The Cheeky Proletariat. Photo: Shahanah Shivji.

Ogundele, Lewis and I all share stories of conversations we’ve had with neighbours frequenting nearby Pigeon Park, or creative and curious passersby whose attention is caught by the art. The Rainier Hotel, across the street, is a treatment and supportive-housing facility for women in recovery. Ogundele tells me the women there “felt safer because there was a light on at The Cheeky. I think of it as a porch light.” In just a few years, the storefront has provoked and welcomed much observation and comment. True of visual art generally in the neighbourhood, stopping in front of the 320 Carrall Street installations will inevitably lead to a conversation with someone, facilitated by the art. How our roles as an audience will unfold in the coming months and years is mutable and undetermined. A space that need not be entered, isn’t attended to daily, where there is no entrance to gain, no surveillance or gallery security to withstand and no art vernacular required—this relatively unassuming venue lends possibility.

A minute away from the (topple-able) monument to Gassy Jack—what Google Maps calls a “statue honoring [the] settlement founder”—I wonder the fate of the small and humble case of The Cheeky Proletariat. Ogundele notes that zoning laws do not sufficiently protect small creative spaces like this one. She worries that “the whim of a couple people complaining that the light is too bright could impact its ability to operate.” Through her curatorial efforts, Lewis challenges the appropriation of Black culture that excludes Black creatives. About Black aesthetics, she asks, “What does that mean in Vancouver? What does it mean for me, sitting right here, on Cambie Street? Because from this vantage, that aesthetic has yet to be built.” Further to the point, perhaps, is that what has been built still struggles to hold, to be visible and meaningfully present. Ogundele’s point, that “there is a community here that’s actually asking to be a community,” is galvanizing. Physical, artist-run space is a critical aspect of our alignment. We need to be able to keep the porch light on.

View of “Where Are You From?” opening night, February 2016, at The Cheeky Proletariat. Photo: Kirsten Roy.

View of “Where Are You From?” opening night, February 2016, at The Cheeky Proletariat. Photo: Kirsten Roy.