MARIE-CLAIRE BLAIS: My background is in architecture. I never studied art in the context of an art school. So I’m an autodidact in the way I play with materiality in my practice. As an architect, I was trained to have ideas or visions about the city. But it was always really abstract; I was really far from materiality. Becoming an artist gave me the opportunity to connect that thinking to the process of making. I’m really interested in space—not just as a black box or a white box, or whatever colour you want, but the idea that there is space between us, around us, and it’s always changing and reconfiguring…it’s fluid. That’s why I’m not really connected to one medium, maybe a bit like you Caroline, I think. I’m concerned with space, material and time in my process as being fundamentally connected to the way we experience the world. This links with your last project, Julie, these beautiful works in Plexiglas—it’s a way to see something from many different perspectives, something that really interacts with the viewer, especially through movement. I’m always looking for something that relates to the idea of uncontrol, something that is not fixed or formatted.

JULIE TRUDEL: I was trained in communications and public relations. I only started to study art part-time in my late 20s. But I was always fascinated by painting; for me it has always been at the top of anything a person can achieve. So it took a while before I considered myself worthy of even trying to become a painter. Of all of the other fields of contemporary art I discovered in art school, my thinking never left painting. I have always been interested in colour first, but trying to work with colour in a new way. It’s like I’m continuing this legacy of the avant garde—trying to work the colour, but through the processes and the materials. Now I’m working with materials that come from design and sculpture. That’s a surprise even for me because I have never been interested in sculpture, or anything that isn’t painting. This is still very much a project about colour, but I also like getting involved with materials…Plexiglas is very challenging, so I love it.

CAROLINE MONNET: I also come from a different background [all laugh]; I studied sociology and communications. I don’t have any formal training in art. I started by making short experimental films. It’s pretty recent that I’ve been exploring different mediums, particularly sculpture and painting. At first it was because I was tired of the traditional theatre setting of sitting and watching. I wanted my work to interact with the public. Now I’m using a lot of industrial materials, like concrete or Styrofoam. I like to work with materials that I can’t totally control—water on concrete, I can’t control the water; or fire on wood, I can’t control the fire. I’m excited by design that is very contained, but a process that I don’t have full control over.

Marie-Claire Blais, Jusqu’où aller, entendre le vent siffler/How far to go, hearing the whistle of the wind, 2018. Pigmented white of meudon and acrylic on burlap, 1.21 x 1.37 m. Courtesy Zalucky Contemporary.

Marie-Claire Blais, Jusqu’où aller, entendre le vent siffler/How far to go, hearing the whistle of the wind, 2018. Pigmented white of meudon and acrylic on burlap, 1.21 x 1.37 m. Courtesy Zalucky Contemporary.

MCB: This is very interesting. The way we have planned and inhabited the earth, everything is controlled because it’s a way to connect everyone, a way to fit the mould. This idea of uncontrol introduces a glitch that breaks those rules. For me, it’s part of creativity to let things go sometimes. In my recent work I’ve been using painted canvas as a material that I fold and cut. It’s the idea of working with something that you’re not controlling, that is irreversible…there’s no undo, undo, undo [laughs]. Now it’s done, but why? What’s going on? What’s next? I don’t know if you’ve read Henri Bergson, the philosopher, but he wrote a lot about evolution and the idea that nature is not planned, that evolution is made of uncontrolled things, that there’s no master plan, it’s something that grows and evolves and we say, okay, we’re just going to follow that road, and then find out it’s not good, so we need to choose another way. My process is very similar: to react, readjust and evolve through making.

Caroline, I’m really interested in your work Anomalia (2010). There’s something about the time lapse behind it, and the moments where images overlap. The transitions are really sensitive.

CM: Anomalia was the first time I did something that is not video. Identity and stereotypical ideas of Indigenous people are always embedded in my work. I wanted to deconstruct these stereotypes and recreate the narrative. So that’s where the idea of cutting up comes from. In film, that’s what I’ve been doing with editing as well: putting images together to create a new mythology, a new, positive narrative, that gets away from these preconceptions. And the lines are always there. Even up to now, they’re still very present in what I’ve been doing. It’s tracing; the idea of traces.

JT: It’s interesting how you are both talking about this idea of uncontrol. In a way, all of our work could look from the outside like it’s very controlled. But uncontrol is something I relate to. I feel like this creates a kind of paradox in painting: if it’s very controlled, it becomes very stiff; if it’s too loose, it’s just not a painting. But tension between both makes the painting very alive. Often I feel the uncontrol is in the material. Caroline, you were talking about water and concrete, but I’ve been working with forming processes for Plexiglas so that the results look almost digital or machine-made. A big part of my interest in this is trying to gain that kind of control over a liquid material that in the beginning is almost uncontrollable. Once I’ve controlled it, though, it’s just not interesting anymore. [all laugh]

CM: How do you get to that level of control? By training? By experimenting?

JT: Training, for sure. One of the things I’ve discovered as a painter, and maybe this is the part that for me is more feminine, is that at some point I felt like I worked more like a craftsperson. Like knitting…repeating, repeating, repeating up until every stitch is the same. My paintings were like that. But it’s part of the process, having the patience to get through all those details and difficulties to find a harmony with your materials.

CM: Like becoming a master of your medium?

JT: Yes, but I would never describe myself as a master. It’s more like I’m learning and the technique informs me. For me the way a project starts is from a challenge. It’s like, these colours are so horrible, the silkscreen colours, CMYK. Is it possible to paint only with those? So it starts like this, with this crazy limitation. But then it’s almost as if I use the methodology of the avant garde, without the grandiose attitude. Everything has been done with black and white, so what can I do with black and white? One of the results of my process is that I have to deal with limitations, and I have to force myself to open up my ideas of what a material can do. Working with Plexiglas is a bit the same. I am fascinated with it, but at the same time it’s really horrible. So for three years I was dealing with fluorescent Plexiglas and it got me really excited, especially because it’s not really about improvising at the beginning; it’s research.

“There’s a lot of value in becoming a master of your technique. For me, though, it’s often the concept that dictates the medium.”

CM: I understand wanting to discover what it’s going to look like if you work at it. You need to be perseverant, like you said. You don’t know at the beginning…it’s like putting together pieces of a puzzle except you don’t know what the end image will be. That’s very exciting.

JT: How about your experimental films; do you work with scenarios?

CM: It depends. At the beginning I was interested in the avant garde—blackand- white, 16 mm, hand-processed. I like the gritty look. Now I work with scripts, and I’m starting to work with actors…I’m going to do a feature film, which is a whole other thing. The smaller projects are more artistic videos made for gallery spaces. The themes I’m exploring are always the same, always social interests, talking about identity and Indigenous narratives. The more I started to move toward visual arts, the more I started to work with narrative cinema. It became two different disciplines and wearing two different hats. I need both of them. When I research for a film project, it’s image-based. I look at a lot of paintings and photography. I think that also informs what I want to do with painting and sculpture. Materials, colours, textures—they always inform each other. But the themes are always, I think, the same. It’s about how we act within colonial power dynamics, within urban settings.

JT: How did you end up doing 2-D work? It seems like almost a contradiction; you’re very much interested in space and sculpture.

MCB: There’s always a depth in my work. There’s a challenge to the way we perceive the surface of the painting. That’s really important. I’m doing painting, but also sculpture and video, so for me it’s not just about being skilled in one medium; it depends on what I have in mind for the work that’s coming. Right now I’m working with burlap. I did a residency in Mexico five years ago and when I came back I decided to work with burlap because it’s an urban fabric used for material transportation. It’s cheap, you can find it everywhere and it’s strong. With architecture there’s always the idea of knitting the urban fabric. So when I’m working with burlap, I’m working with the city. Recently I became interested in the painted facades of buildings in Rome. I’m working now with painting that comes from this urban landscape, mixing dry pigment and layering it over burlap then cutting it. It’s not a picture that always makes sense, it’s not always easy to perceive, but that in-between is what interests me. That’s why I like it. I like to cross the line, to try to think about the conventions of painting: the frame, the canvas, a slice through the canvas, removing the frame…a way to keep questioning the conventions. Maybe coming from another field of studies gives me the freedom of the outsider.

I was interested when you said that painting has always been the biggest art form in your mind. It makes me think about classical paintings, about the Old Masters, but your work is so modern…

JT: Yes. I’m interested in all of it. I had a government job and for all of my vacations I left for a month and visited museums in Europe, every day from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. I travelled across Italy just to see paintings. Not only the Old Masters, but also Impressionist paintings and everything else. I was trained as a figurative painter, but I never had any subject matter that I was attracted to at all. I did a lot of life drawing, but at the end of my bachelor’s degree I realized I was really interested in the technique. You start with line drawing, and then once you become good you switch to charcoal, and then watercolour, and in the end I could draw a full portrait in colour in two or three hours, but there was nothing I had to say. I was interested in the process and learning about colour and drawing, but that’s it.

CM: That formal approach is super important. It’s the same thing in cinema; there are filmmakers who work only with light and they become masters of light and colour. There’s a lot of value in becoming a master of your technique, and experimenting and pushing that technique further. For me, though, it’s often the concept that dictates the medium. These are very different approaches, but I think both are valuable. Art needs it. Art needs to be challenged.

JT: Yeah, but for me, it’s still more a learning process. I’m always a little bit upset when people praise painting as “skilled” or “well done.” Although I do think that is part of what makes a good painting, it seems like an argument that is old-fashioned and outdated. Mastering a technique, for me, doesn’t have any value alone…the work has to breathe and it has to have meaning.

MCB: That’s because you are a master! [all laugh]

Caroline Monnet, Foamular, 2018. Engraving on Styrofoam, 102.8 cm diameter. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie Division. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Caroline Monnet, Foamular, 2018. Engraving on Styrofoam, 102.8 cm diameter. Private collection. Courtesy Galerie Division. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

CM: Right. You have that freedom to experiment because you’re not indebted to a certain tradition of the university. Because I’m also self-taught I realized that I needed to learn by doing, to find my own ways of doing. So you find your own technique, you find your own way of working with it, and somehow it works. Sometimes other artists will say, “That’s not how you’re supposed to do it,” and you can learn from that too. But at the same time, the process that brought you there is as important as the result. I love when you talk about challenging the medium or challenging the way of doing it, removing the frame and deconstructing the materials.

MCB: It’s like doing by a process of undoing, by a process of deconstructing or removing. I’m much more interested in the creative process of subtraction rather than addition. Maybe that’s characteristic of my way of thinking, probably also outside of the artwork! [all laugh]

JT: It makes sense because you’re interested in the space between the object, and the space being created by that in-between. In painting, the tradition is very stiff, and it may be easier to make the void between more apparent in the painting than in the sculpture. And maybe for you, Caroline, it’s a little bit the same? The frame of the video in some of your works seems to play the same formal role as the structure of a canvas. You also play a lot with collage in your videos. Maybe the point is that painting is so stiff as a tradition that it’s easy to deconstruct. And anything that you put in a frame becomes a painting, basically. But if you leave the same material in real space, it stays functional.

MCB: But it really comes down to the culture. In certain cultures, burlap can be a religious or ritual material. Depending on where you come from, or what your background is, it can change the meaning of the material.

“This idea of control and uncontrol, black and white, dark and light. This is for me what makes a work, to keep that tension.”

CM: I think material carries its own history, its own language. For a recent series of works, I sourced cedar from my mom’s community in Maniwaki and then brought it back, glued the pieces of wood together and had them laser etched. The designs are burned into the wood, so the work actually smells. And I remember the first paintings I did in 2012 were because I wanted to talk about the teepee as being the common icon or stereotypical idea of all Indigenous people across Canada. My people never had teepees. They lived in longhouses. So it was to speak about the differences across Canada, that all nations are not the same, that they don’t all have the same traditions or languages. Because I was talking about the teepee, canvas became the medium I wanted to use and that’s why I started painting. That was also the beginning of doing these more complex geometric designs. So again it’s speaking to my relationships to the material, as research but also the physical material. And because canvas can be folded and shifted, they are actually like the teepees. The actual physical material of the canvas became the reason for the paintings.

JT: Where do your patterns and designs come from?

CM: It’s inspired by traditional Anishinaabe design that is passed down by the matriarch in the family. I redo them on the computer and revisit the designs from a conceptual perspective. Traditionally they’re made using the birchbark technique, which creates a symmetry. You bite a piece of birchbark with your teeth, then you open it up and it creates this amazing, intricate design. That’s what I try to do as well; I make a pattern and then I make them symmetrical. For me these also resemble city maps, QR codes or microchips…and they’re inspired by Op art as well.

JT: Do you feel any connection to modernist painting?

CM: That’s what I like when I look at painting. I like geometry, structure, lines and textures. I’m interested in architecture. I’m interested in modernism and urban planning. And when we talk about concepts of time, I think geometry is rooted in traditions of all cultures in the past. It’s also what brings us into the future with things like quantum mechanics and binary codes. Concepts of the past, present and future are rooted in geometry.

MCB: When I started making paintings, I was fascinated by the triangular shape. But my work is getting rougher; I’m looking more and more for imperfection. This is the thing about architecture that you have to be careful about, because you become a perfectionist. You are looking at every detail as something that could have been done better. I think being in Mexico, and spending time outside of Montreal, made me realize that our surroundings here are very flat. Even for the spirit. The way we build space, it’s very simple, there’s no complexity…it’s not challenging, mentally or physically. When I came back from Mexico I realized that it had really changed the way I see space and I tried, as I said, to bring some imperfection to my work. I wanted to be more engaged with my body, to find another way of working with painting. I need a kind of closeness with the work.

JT: It’s funny because you describe your painting process and it’s very physical, the body is involved a lot. But in your paintings themselves, the trace of the hands, we don’t see this. I would say they are masterful [laughs]; they’re very alive. But to make that big and complicated is a serious challenge.

MCB: I like to disappear behind my work. But that’s changing. It’s difficult because some projects are very visual, they are connected to memory, so I want to remove the hands, the process of making from that. Other projects I’m working on are much more grounded in the physicality, the reality of gravity. For example, I did some welding in the studio, sculptural pieces that I’ve never shown. It’s like we were saying before, this idea of control and uncontrol, black and white, dark and light. This is for me what makes a work, to keep that tension. The idea of positive and negative is essential.

CM: Is it essential in the work or in the artist?

MCB: Everywhere, I think. I’m also always thinking about the idea of limits. A limit can divide but it can also connect at the same time, like a border, or skin. It breathes, it creates an exchange, but at the same time it limits our body. For me, a limit is the place where you negotiate everything…politics, everything.

CM: But it’s never just black or white.

MCB: No, no, no. It’s always more.

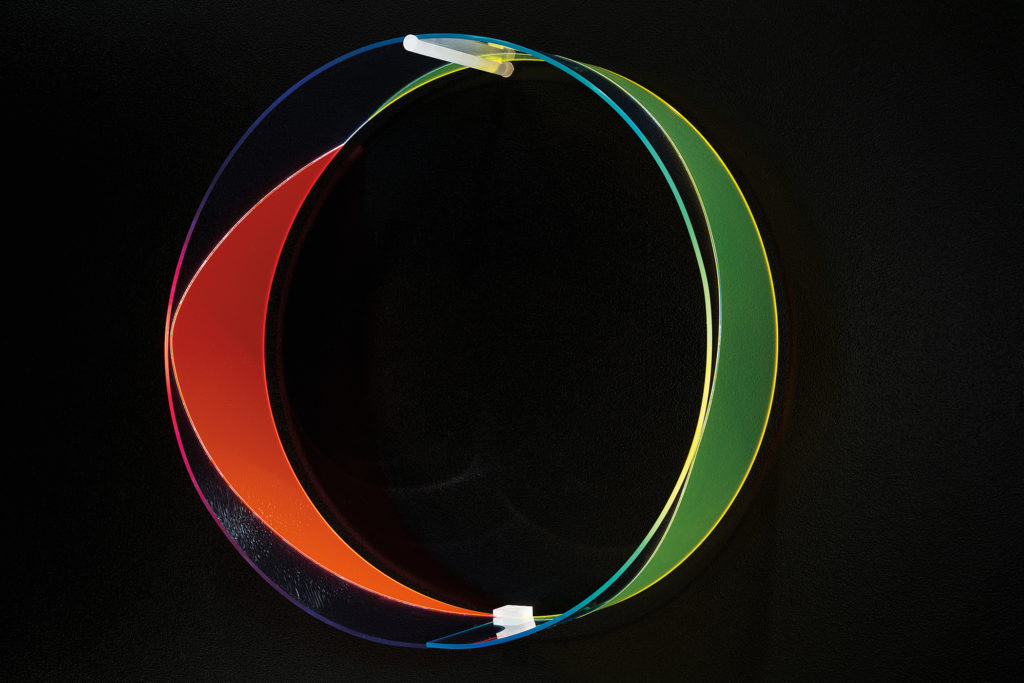

Julie Trudel, Carré éclaté J/B + R + Blanc, 2018. Acrylic paint on folded and assembled coloured acrylic sheets, 106 x 64 x 65 cm. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau. Photo: Jean-Michael Seminaro.

Julie Trudel, Carré éclaté J/B + R + Blanc, 2018. Acrylic paint on folded and assembled coloured acrylic sheets, 106 x 64 x 65 cm. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau. Photo: Jean-Michael Seminaro.