Everywhere we see that there is an aesthetic component to the brutalities of a world where the pace of everyday life vibrates with Native misery. Think, for example, of the deep visuality of the slow killing of Barbara Kentner, a First Nations woman living in Thunder Bay. On January 28, 2017, Brayden Bushby, an 18-year-old white man, threw a trailer hitch at Kentner. Bushby was in a moving vehicle when he spotted Kentner. But, “spotted” cannot quite apprehend the affective lineaments of the subject-object relation that likely animated Bushby’s actions. It was reported that just before Bushby turned Kentner into a ghost he said, “I got one!”

What did Bushby see? In his formulation, “one” brings into focus a sinister optic, where “optic” is the lens or filter by which one looks and from this looking ropes what is seen into an encounter humming with all sorts of potential. Bushby’s is an optic that mediates the interpellative call “one” seeks to enact—it is a part of the grammar of settler horror. “One” is thus a modality by which we, the ante-Canada, those of us who bear that which is prior to and beneath Canada, are racialized and roped into a representational field where all things, like trailer hitches, can be put to violent use. We cannot survive in the visual register of “one.”

Words are worldly; not just in the sense that they proliferate and float up into the sky and become cloud-like. Words world too. Words like “one” incubate death-worlds (see Achille Mbembe’s 2003 essay “Necropolitics”) inside which those of us who look like Kentner are made to inhabit modes of enfleshment that fix the stares of the grim reapers of the present. On the other hand, some of us recruit words in the name of something like freedom. We might call this duality the double-bind of enunciation. How do we refuse a savage call to being with a more spacious one?

Joi T. Arcand, Amber Motors, 2009. From the Here on Future Earth series. Courtesy the artist.

Joi T. Arcand, Amber Motors, 2009. From the Here on Future Earth series. Courtesy the artist.

Joi T. Arcand is a photo-based artist and industrial sculptor from Muskeg Lake Cree Nation, and she knows that words, that letter forms, shapes and glyphs, “change the visual landscape,” that they are how we go about practicing new ways of looking. Words are emotional architectures, and Arcand calls hers “Future Earth.”

In her 2015 book The Argonauts, Maggie Nelson tends to a debate about whether words do or do not potentiate. She takes up a claim of a partner’s that words do nothing but nominalize, and what is left unnamed is subject to a host of horrors. Nelson, however, holds out more hope for words; she contends that they are “good enough,” that how one speaks makes all of the difference and that words can, following Deleuze, incite “the outline of a becoming.”

Bushby’s angered vocalization of a genre of non-being—where “one” is the refusal of a name and the humanity that comes with it—is evidence of the terrible mechanics of language. But, it is in opposition to this linguistic state of killability, this metaphysics and rhetoric of coloniality, that Arcand articulates a grammar of subjectivity vis-à-vis the time and space of a native future.

Joi T. Arcand, Northern Pawn, South Vietnam, 2009. From the Here on Future Earth series. Courtesy the artist.

Joi T. Arcand, Northern Pawn, South Vietnam, 2009. From the Here on Future Earth series. Courtesy the artist.

Here on Future Earth is a series of photographs that Arcand produced in 2010. In a phone interview, Arcand explained to me that this is where her photo-based practice and her interest in textuality synched. Arcand wants us to think about these photographs as documents of “an alternative present,” of a future that is within arm’s reach.

For this series, Arcand manipulated signs and replaced their slogans and names with Cree syllabics. By doing this, Arcand images something of a present beside itself and therefore loops us into a new mode of perception, one that enables us to attune to the rogue possibilities bubbling up in the thick ordinariness of everyday life. Arcand wanted to see things “where they weren’t.”

Hers is not a utopian elsewhere we need to map out via an ethos of discovery. Rather, Arcand straddles the threshold of radical hope. She asks us to orient ourselves to the world as if we were out to document or to think back on a future past. That is, Arcand rendered these photographs with a pink hue and a thick, round border, tapping into what she calls “the signifiers of nostalgia.” Importantly, these signifiers are inextricably bound to the charisma of words, to the emotional life of the syllabics. The syllabics are what enunciate; they potentiate a performance of world-making that does not belong to the mise-en-scene of settlement.

Joi T. Arcand, Sweetgrass Store, 2009. From the Here on Future Earth series. Courtesy the artist.

Joi T. Arcand, Sweetgrass Store, 2009. From the Here on Future Earth series. Courtesy the artist.

It is this mise-en-scene of settlement that Arcand conjures to then obliterate, which is to say that her photographs evince a prairie world that is crowded with meaning, meaning that belongs differently to the logic of terra nullius (that a place exists without history or politics prior to European settlement) and to myths of Indian savagery and degeneracy. It is against this system of signs that Arcand opens the prairies up to radical resignification. It is where we build a future atop the decayed remains of coloniality.

Perhaps Here on Future Earth visually captures the tempos of “Indian time,” which is always a scene of errant temporality. Indian time is less about the absence of rhythm and more about an inability to fix or to analytically hold up the rhythmic as a mode of feral movement itself. Words like “one” are spun such that they stomp us into the rut of social death. But: Indian time evinces an otherwise kinetics.

In Here on Future Earth, this kinetics is energized by the textual, by the stories that they tell, and their visual culture. The modified signs exploit our ability to look; that we see them and conceptualize them as out of place or untimely is how we transport ourselves to a different time, to a place governed by Indian time. The syllabics themselves map a visual field. This is what Arcand calls “the optics of the language.”

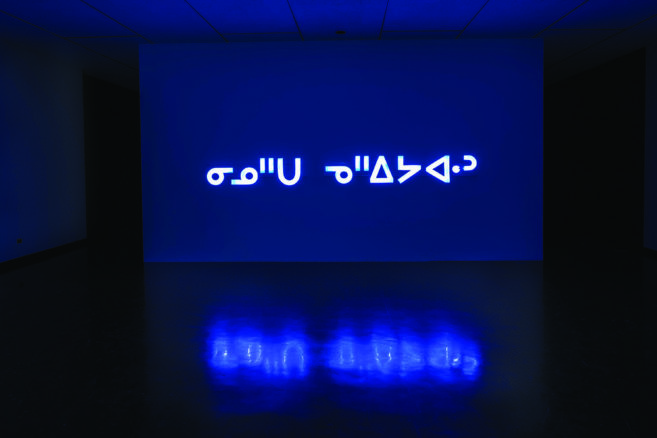

Joi T. Arcand, Installation view of “ᓇᒨᔭ ᓂᑎᑌᐧᐃᐧᓇ ᓂᑕᔮᐣ” (2017). Courtesy of the artist. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Rita Taylor.

Joi T. Arcand, Installation view of “ᓇᒨᔭ ᓂᑎᑌᐧᐃᐧᓇ ᓂᑕᔮᐣ” (2017). Courtesy of the artist. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Rita Taylor.

It is around these words that sociality orbits. This thematic persists in Arcand’s latest project, a set of large neon signs that light up Cree words like keyam. For Arcand, all of her engagements with the Cree language are partly elegiac. She is mourning language loss, but puts this negative affect to rebellious use to signify a world-to-come. Like the syllabics in Here on Future Earth, the bright signs prop up affective structures for a time and place where our relations to Cree are not always-already bound up in performances of grief.

In one sign, Arcand translates the English phrase “I don’t have the words” into Cree. “I don’t have the words” is a paradoxical speech act; it uses words to announce their absence. These signs are installed in gallery spaces where Arcand’s work is commissioned; one was recently installed at the second gesture of the Wood Land School at the SBC Gallery of Contemporary Art in Montreal, another outside the Walter Phillips Gallery in Banff. These signs interrupt the visual terrain of the gallery, as if welcoming onlookers to a new world, to a new geographic form. The signs something like kinship around a common wordlessness in the service of a new world-making praxis.

These photographs and signs, then, are all relics of a future past. They emerge from something of an anthropological interest in a future-in-the-present, in the affects of Indian time. Arcand thus writes the world wrong so that she can write it anew.

Billy-Ray Belcourt is from the Driftpile Cree Nation. He is a PhD student in the Department of English and Film Studies at the University of Alberta.

Joi T. Arcand, Town Hall, 2009. From the Here on Future Earth series. Courtesy the artist.

Joi T. Arcand, Town Hall, 2009. From the Here on Future Earth series. Courtesy the artist.