The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts recently announced a unique promotion: it is offering physicians in Quebec the ability to prescribe a free trip to the museum for some patients, suggesting that “the arts stimulate neuronal connectivity” and provoke “richer, more complex neural activity.”

Why do so many arts institutions have a fascination with neuroscience? It’s clear, on the one hand, what art can do for neuroscience: it provides an area of study that pushes the boundaries of the discipline. Examining how the brain processes art experiences is providing scientists with new information about neural anatomy. While brain function can be fascinating, most museums aren’t trying to chart the organ’s working parts.

So here is a better connection: the fields of art and neuroscience both help us think, philosophically, about how we interact with the world. Unfortunately, that thinking is sometimes muddied with oversimplifications about how our brains process the experience of art—and in simplifying the explanation, it’s implied that the value of art lies solely in its provision of pleasure and gratification, as well as in the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, when in fact many other neurological phenomena are involved.

Incorrect assumptions turn up in the way artists, curators and museum directors easily accept premises about neuroscience that they would never accept about art alone. News stories about neuroscience often imply that brain research provides fundamental, universal information about the human condition. In the field of art, however, universalizing claims have largely been debunked. Most contemporary artists and critics would hesitate to claim that a given artwork could trigger the exact same response in all viewers.

We generally understand that social conditions inform perception, and that an individual brings their own lived experience to every artwork they encounter. But when it comes to art and neuroscience, these understandings seem to fly out the window. Take the following headline-style statement promoted by the UK organization Art Fund, for example: “Art Gives Same Level of Pleasure as Being in Love.” This is the title of a video produced by the arts funding agency to promote a national art pass that encourages attendance at galleries and museums. It features neurobiologist Semir Zeki, who is a pioneer in the field of neuroaesthetics—a relatively new field aimed at studying how humans process beauty and art.

The video opens with a shot of people looking at art in a gallery, with a voice-over narration that states, “Art lovers have long thought that art is important to our well-being, but they had no proof, until now.” The proof—as this Art Fund video relates it—is that Zeki’s lab performed experiments that found the experience of beauty activates pleasure centres in the brain, releasing the chemical dopamine, or, in Zeki’s terms, the “feel-good neurotransmitter.” The goal of the video is clear: neuroscience is invoked to validate art experiences, and convince people to buy an art pass.

Like other media coverage of its kind, this video is deeply patronizing to art lovers and misrepresents the neuroscience of pleasure—it even misrepresents Zeki’s own research findings. The video leaves viewers with the following arguments: that science validates art, that art is all about beauty, and that the specific Western artworks that appear in the video will trigger a universally positive response, making it seem as if looking at art is akin to pushing a pleasure-button in the brain.

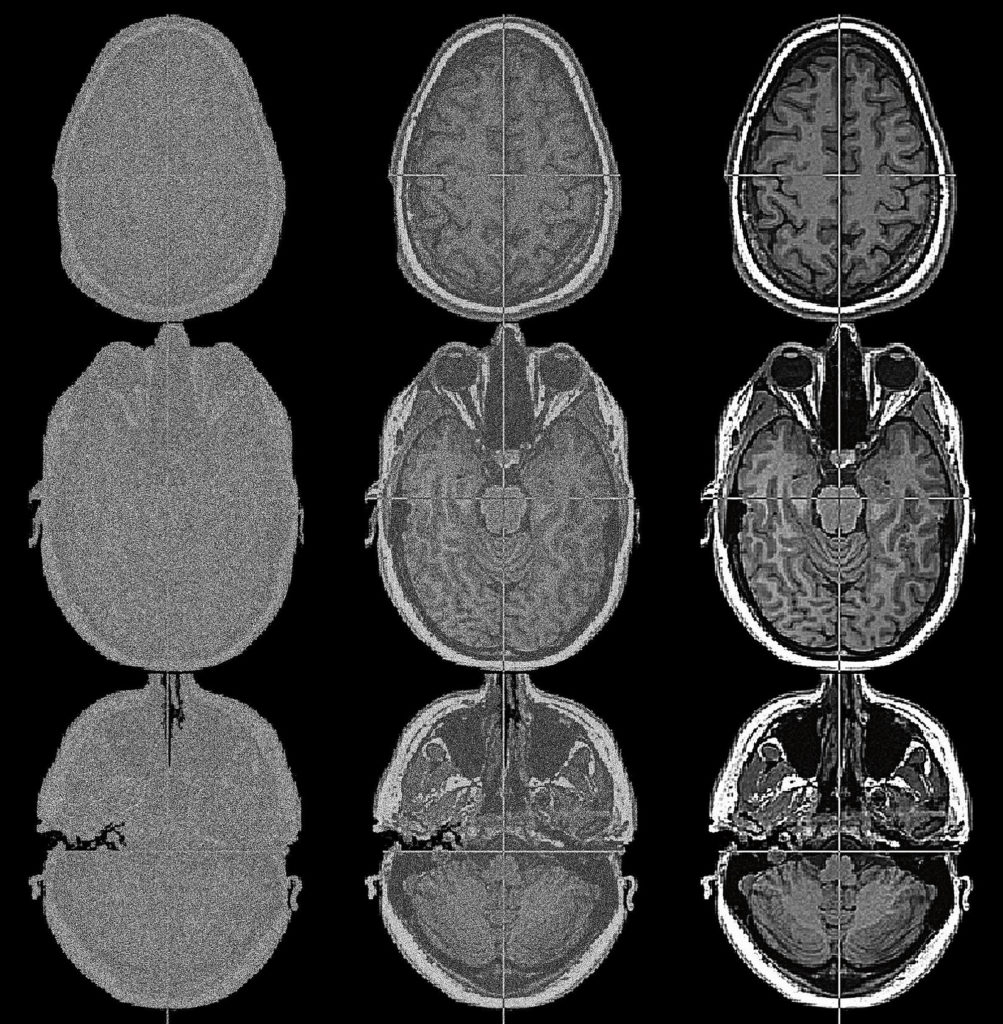

Sally McKay audited a course in brain-scan technology at York University in 2010. As part of the course, students in the class designed experiments for the MRI scanner, and then went into the scanner to be subjects for each other’s projects. These images are Sally’s brain, scanned during one of her fellow students’ experiments.

Sally McKay audited a course in brain-scan technology at York University in 2010. As part of the course, students in the class designed experiments for the MRI scanner, and then went into the scanner to be subjects for each other’s projects. These images are Sally’s brain, scanned during one of her fellow students’ experiments.