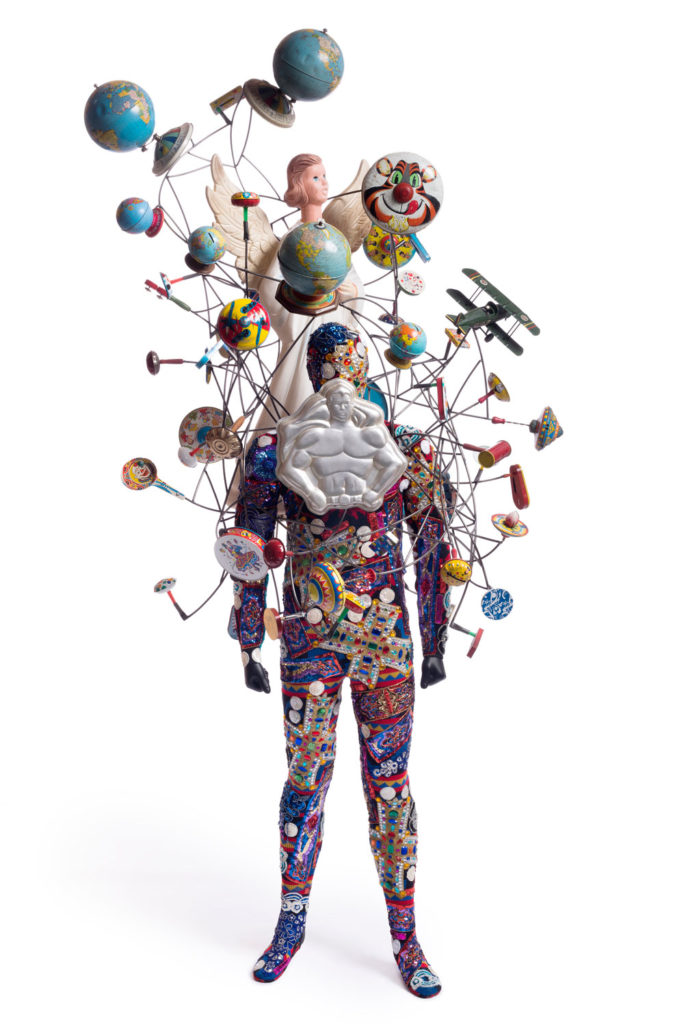

Yaniya Lee: The soundsuits are celebratory. They’re big, they’re colourful and they’re dynamic. But there’s a contradiction in there for me: while they’re free, they also conceal extreme vulnerabilities.

Nick Cave: It’s protecting, it’s isolating, it’s shielding. There’s a sense of feeling liberated but you also have to understand that being in a soundsuit [means having] to surrender a part of yourself. There’s a transformative moment. In order for you to be what this is, you have to be willing to transmit to something other. How are you going to convince me that you’re being a soundsuit, not just wearing a soundsuit? That whole idea of being is all about this sort of transformative shift. How do you settle down in order to receive this other?

YL: How do you make yourself open enough to experience whatever it’s like to be in the suits? How important is movement to their activation?

NC: If I’m working with you I have you sit across from the soundsuit, and I have you write about what you are encountering, what you are looking at. Then I will have you touch it and pick it up and connect with the weight, how visceral it is, and then I will have you move closer to it and again allow you to engage with this thing that you’ve just encountered. Then I will have you put it on.

I particularly like working in a space where there’s a mirror, let’s say a dance studio, and I will have you stand there, let’s say 20 or 30 minutes and describe what is happening. You do not move! Then I will slowly allow you to move. You have to transition.

People don’t understand that the suits already do 60% of the work, so you could walk to the end of the stage and just stand there and project—meaning, get your core up and don’t move at all. It’s always you and maybe 30 other soundsuits. So, honey, just that alone, that you are amongst a peer group of extraordinariness in the hybrid tribe [and] you all have common language and you start to build this entire narrative.

YL: What is this narrative? What typically happens in these performances?

NC: It depends. The last project we did was a performance piece titled Upright. It’s a piece that’s a rite of passage. It’s a piece about and for young Black youth—particularly men—that have not been given the tools to transition from childhood to manhood.

We worked with 15 kids from an LGBT centre for runaway youth in Detroit. We’d strip them down, in front of an audience, to black shorts and a tank top. They’d fold their clothing up, stack it on the floor and put the shoes on top, then they’d proceed to sit down on a stool as we adorned their bodies and [dressed] them back up. At the end they’d have completed this entire ceremonial rite of passage, and we’d give them a certificate to tell them that they have now become warriors who are now able to go out and stand tall.

YL: People activate your suits by dancing in them or you orchestrate performances of dozens of people wearing your soundsuits . How would you describe those ways of being together? Are you creating a new social space?

NC: It starts on so many levels. Because what I tend to do is bring a project to a city then hire the city to build the project. Even before they are in contact or even see the soundsuits I ask, “Who’s here? Who lives here?” And I want to know all the dancers that are there, all the musicians, vocalists, movers. I’ve found that I introduce a city back to itself in these collaborations where I work with a group of a hundred artists. The word “accountability” [becomes] important for people. People want to be accountable for something that matters. [So] how do we create projects where each person matters? We hire the community! [And they are] left with this imprint forever, of being a part of something that they built. That’s really my sort of mission work: I want to be of service. I want to use my work as a form of service. And a form of service for me is investing and reinvesting in communities. That’s what it’s all about. I’m creating a platform for you to stand on and to realize that this is possible. Because I’m on it and I am blessed and I have gratitude. Why not provide an opportunity for someone [else] to go, “Wow, I am here performing!?”

YL: I can’t leave without asking about sound, because again, though the suits conceal class and race and gender, the sound takes up space and creates this different presence.

NC: I am using sound as a form of alarm. Sound doesn’t always have to be heard. You can hear sound through pattern, [and] how pattern is set up on a surface to create a rhythm. Colour can also create a sense of sound. Just use a police car for example: if you don’t hear the siren but you see the red lights, you know what that means. Sound is signal, so therefore it may be approached that way, or it may be the sound [from the way] the object is built, you know, let’s say all bottle caps. It could be a subtle sound depending on how I engage myself in the object, or it could be really aggressive, which then shifts the dynamic of the sound. Sound can operate out of a state of emergency. It can be calming; it could be peaceful. I’m thinking about being in a soundsuit and how you illustrate and express forms of anger. How am I going to communicate with you through movement without verbal communication? How is stomping my feet a powerful act of communication?