In the summer of 1967, a special issue of Artforum dedicated to American sculpture foregrounded Minimalism, the art movement then taking the New York art world by storm. The previous year, the trademark geometric sculptures of Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Anne Truitt and others had been brought together in Kynaston McShine’s “Primary Structures” exhibition at New York’s Jewish Museum. The Artforum issue followed with a group of texts by Morris, Sol LeWitt and Robert Smithson alongside a polemic by Michael Fried titled “Art and Objecthood.” In this now (in)famous essay, the Modernist critic drew a line in the sand. Minimalism, he asserted, was banally “literalist,” its simple forms reinforcing the “objecthood” of our everyday perception of real time and space. The proper goal of art—exemplified by Modernist painting—was precisely to transcend such objecthood, to focus on art’s pure, optical essence and thus lift the beholder to a realm of disembodied aesthetic experience. What was at stake in Artforum’s 1967 issue was more than just a matter of taste. As art historian Hal Foster has argued, the event of Minimalism marked a “historical crux”: a moment in which the limits of one mode of artmaking (Modernism) become suddenly explicit, opening a space for a new, postmodernist set of practices.

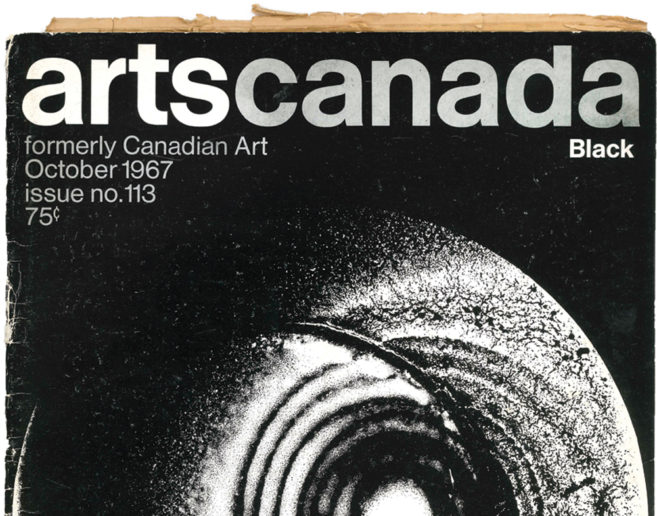

That same summer, the journal artscanada—a precursor to Canadian Art—was at work on its own special issue, this one focused on the topic of “black.” Over the course of the past decade, scholars have begun to explore this issue as an alternative crux in 1960s art, one that offers an alternative history of the present.

The centrepiece of the issue, published in October of that year, was a “simultaneous conversation” between seven speakers, connected by phone between New York and Toronto: Aldo Tambellini, Michael Snow, Cecil Taylor, Ad Reinhardt, Arnold Rockman, Stuart Broomer and Harvey Cowan. The goal was to explore “black” in a variety of senses: “as spatial concept, symbol, paint quality; the social-political implications of black; black as stasis, negation, nothingness and black as change, impermanence and potentiality.” In the conversation’s published form, however, this variety was somewhat eclipsed by the singular vision of the roundtable’s senior figure, the painter of black monochromes, Ad Reinhardt. For Reinhardt, who was a Modernist in the mode of Fried, black was the ultimate expression of art’s transcendence of everyday life. Black’s significance was a function of neither symbolics nor materiality, and it was certainly not any kind of social or embodied experience.

Aldo Tambellini, Black Zero, 1968. Performance featuring Calo Scott at the University of Western Ontario. Courtesy Aldo Tambellini Foundation. Photo: George Ehrlich.

Aldo Tambellini, Black Zero, 1968. Performance featuring Calo Scott at the University of Western Ontario. Courtesy Aldo Tambellini Foundation. Photo: George Ehrlich.

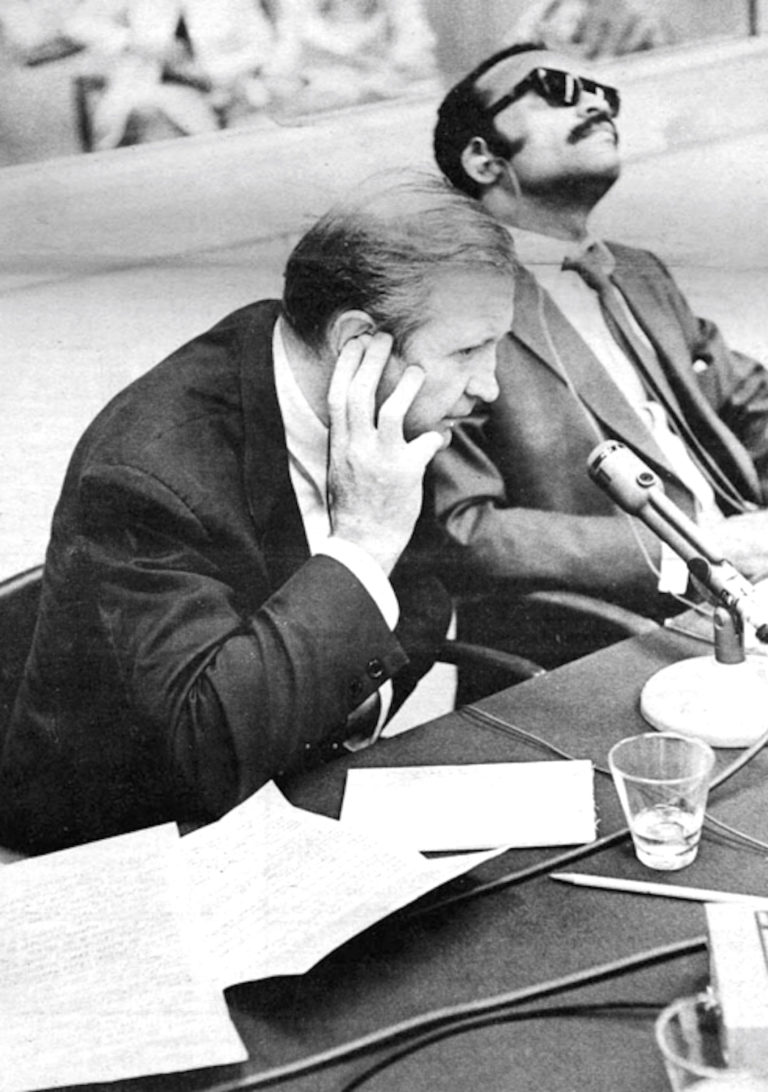

In the roundtable, however, Reinhardt’s Modernism met an unfamiliar (for him) point of resistance in the ideas of Cecil Taylor. The New York poet and pianist, a pioneer of free jazz recognized for his synthesis of classical and modern forms, was the discussion’s only Black participant. For him, black meant “black power”: not only the recently emerged liberation movement, but also the longer history of the “black way of life” that sustained it. As such, directly countering Reinhardt’s evocation of black as an idealized and universalist aesthetic experience, Taylor’s black was contingent and concrete, tied to both the life of his local community and the political struggles of a global African liberation movement.

If Artforum’s 1967 summer issue marked a crux between Modernist painting and postmodernist Minimalism, the artscanada “black issue” pointed to a crossing of a different sort. The failed encounter between Reinhardt’s Modernism and Taylor’s radical Black aesthetics underlined the structural whiteness that defined the art industry of 1960s North America, in both its Modernist and postmodernist guises. As the Black Power movement was at that moment very clearly laying out, such whiteness worked more covertly than other forms of racism, often involving a seeming embrace of both civil rights and Black voices. Yet, as was the case with Taylor, such voices were usually pressured to perform their specific “blackness,” leaving unremarked the condition of whiteness that was assumed to underpin all representation and existence. This, for Frantz Fanon, was the hellish ontological circle that plagued the existence of the colonized: to be forever the “other” to a universal white subject.

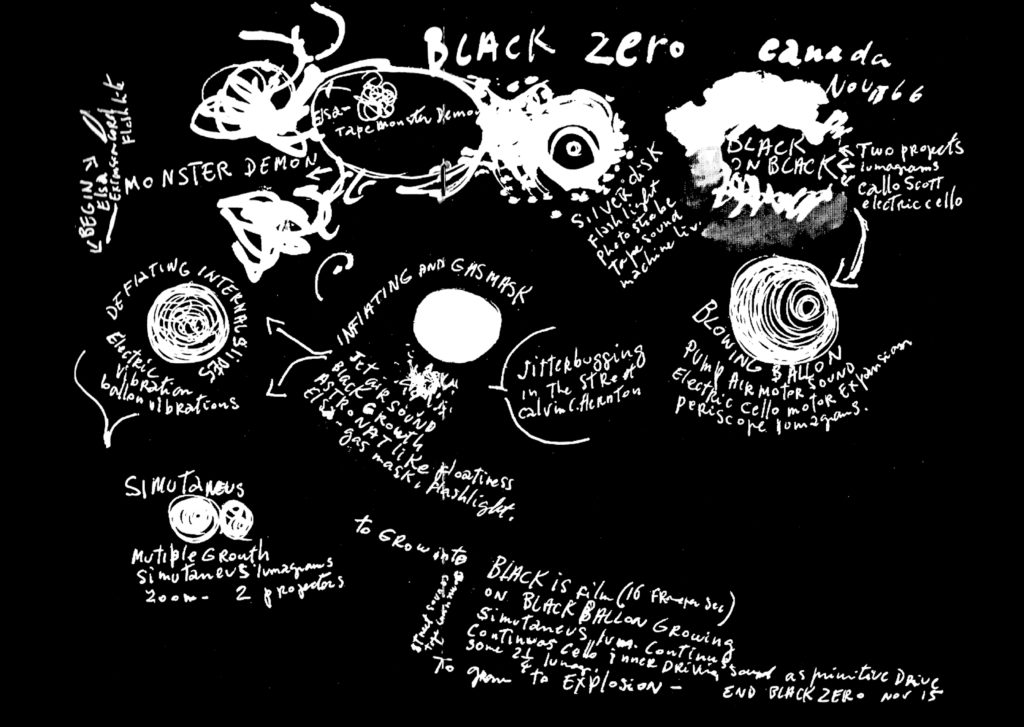

Tambellini’s Black Zero was overwhelming: a bombardment of sensory stimulation, multiplying meanings and explicit evocations of racial conflict. Its environment resulted in an overload of meaning and perceptual stimuli that dissolved any stable sense of self.

While Reinhardt remained oblivious to such racial politics, Anne Brodzky, for whom the “black issue” marked her first as the journal’s new editor, was very conscious of them. In comments omitted from the conversation’s published form, Brodzky mourned the roundtable’s failure to fully confront the question of race. Having recently relocated to Toronto from the US, Brodzky expressed a pointed anxiety about racial segregation and the US’s “growing tendency toward Fascism.” “I feel,” Brodzky explained, “that it is only among such men who are able to express the dignity of what it means to be black and what it means to be white [and in] the amplification of their differences that these forces will be joined.”

In hoping for a mode of integration achieved through the “amplification of…differences,” Brodzky had in mind another participant in the conversation, the Italian American artist Aldo Tambellini. In November 1966, Brodzky attended a performance of Tambellini’s Black Zero (1966–68) at the University of Western Ontario. The work comprised a dark, cinematic environment, which Tambellini punctuated with an onslaught of slides and films of abstract spirals and circles, some projected onto a large expanding balloon that eventually burst. This display, and other iterations of the work, was further energized by a rotating ensemble of collaborators: an improvised dance by Elsa Tambellini, a throbbing bassline from cellist Calo Scott and a recording of a poem by Calvin Hernton about the 1964 Harlem riots.

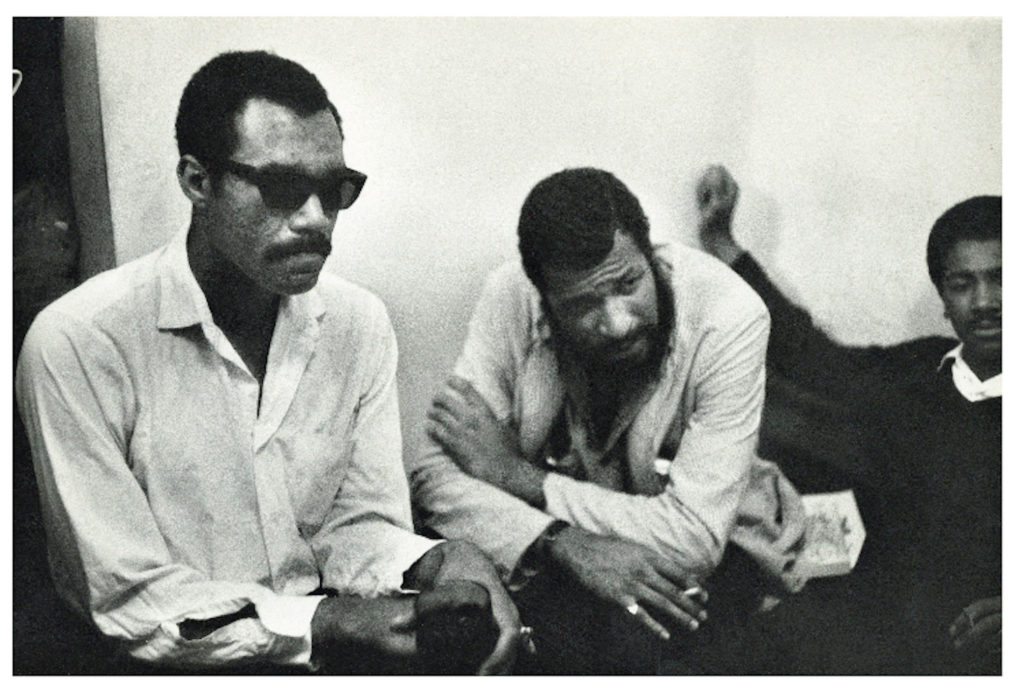

Ad Reinhardt and Cecil Taylor in roundtable discussion organized by artscanada, August 16, 1967. Courtesy Estate of Jesse A. Fernandez.

Ad Reinhardt and Cecil Taylor in roundtable discussion organized by artscanada, August 16, 1967. Courtesy Estate of Jesse A. Fernandez.

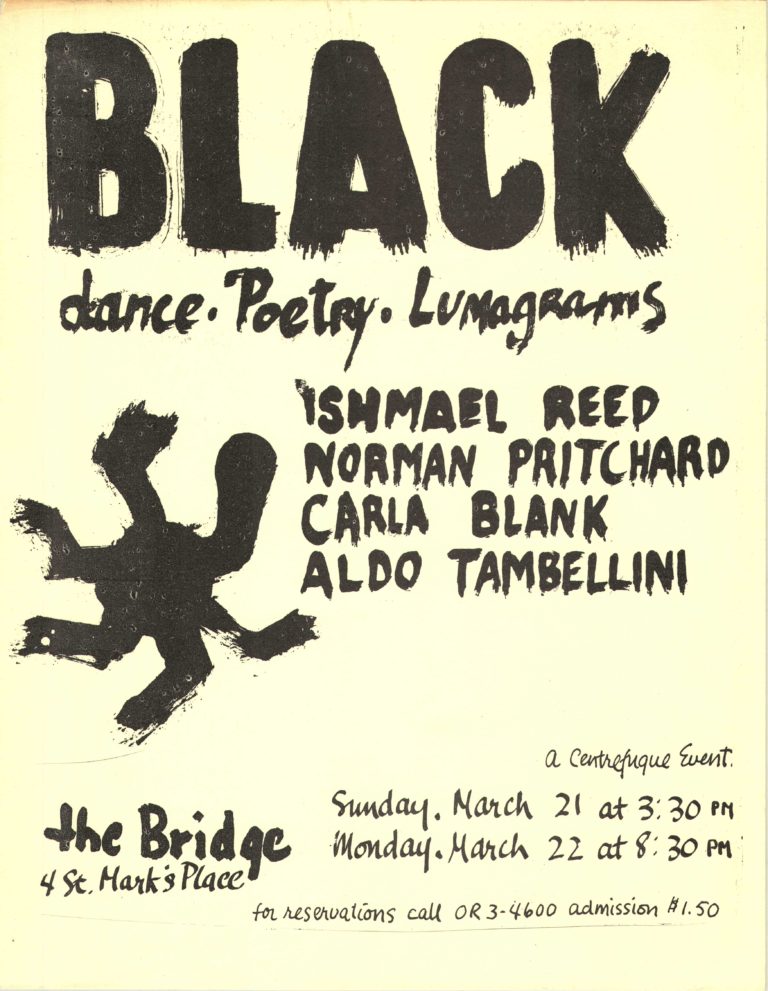

Event flyer, March 1965. Courtesy Aldo Tambellini Foundation.

Event flyer, March 1965. Courtesy Aldo Tambellini Foundation.

Brodzky compared Black Zero to Andy Warhol’s performance series Exploding Plastic Inevitable (EPI), an iteration of which she had seen that same week. Like Black Zero, the EPI combined electric sound (a live performance from the Velvet Underground), lights and multi-screen projections, yet in a way that Brodzky found overly trendy and rehearsed. Tambellini’s work, in contrast, was overwhelming: a bombardment of sensory stimulation, multiplying meanings and explicit evocations of racial conflict. Unlike the familiar embrace of Warhol’s discotheque, Black Zero’s environment resulted in total disorientation for Brodzky, an overload of meaning and perceptual stimuli that dissolved any stable sense of self.

Tambellini’s aesthetic of disorienting abstraction was, like Minimalism, motivated by a desire to break from the assumptions of Modernist painting. After growing up in Italy during the war, Tambellini moved to upstate New York in 1946, where he undertook training in classical and religious art. There he developed a strong distaste for Modernist discourse and its institutions, which he considered elitist and too focused on the individual psyche. For Tambellini, the role of the artist was not to express oneself, but rather act as a kind of medium, tapping into what he described as the “flux” of forces that underpinned reality and translating that flux into forms that rendered it legible for a broad public. Such communication would require what Tambellini and his colleagues of the 1950s called an “integration of the arts,” one that involved collaboration between artists and across media.

These moments of intimacy occurred not between predetermined “subjects” (which, as Fanon tells us, are always silently white), but rather as flashes of spontaneous becoming between creative forces. Such encounters gave expression to a disordering force.

Tambellini’s initial model for this “integration of the arts” was the church, and forms like the crucifix. He soon realized, however, that the most salient forms were to be found in the science and technology of the space age. In images of microscopic particles and macroscopic space-scapes, Tambellini found abstractions that seemed to underpin all organic and non-organic life: the circle, the spiral, and above all, the colour black. Beginning in the early 1960s, Tambellini repeated these forms in drawings, paintings, sculptures and, from 1965, multimedia performances like Black Zero. While for Reinhardt (whose Modernism is often projected onto Tambellini in discussions of the roundtable) black was a transcendent space of negation, for Tambellini it was a form of radical affirmation, an expression of the multitude of forces that permeate everything around us.

Tambellini understood his audience for such abstractions in quite concrete terms. Bypassing the museums he so despised, Tambellini sited his work in the interracial community of the Lower East Side, between 1961 and 1966 opening his studio to local children, working with churches and schools and co-founding the avant-garde venue the Gate Theater. Tambellini’s utopian hopes for an interracial bohemia were tempered, however, by his proximity to the emerging Black arts movement. In his multimedia pieces, Tambellini collaborated with poets like Ishmael Reed and Hernton who, along with Tambellini’s artscanada interlocutor Cecil Taylor, were part of Umbra, a poetry reading group and magazine that operated from 1962 to 1964. To spread their work, the group would often appear en masse at downtown reading venues, combatting white liberal gestures of token inclusion with a wall of exclusively Black content—what Hernton called a “black arts poetry machine.”

Poets (from left) Calvin Hernton, Norman Pritchard and Charles Patterson at an Umbra meeting, ca. 1963. Collection Amistad Research Centre, New Orleans.

Poets (from left) Calvin Hernton, Norman Pritchard and Charles Patterson at an Umbra meeting, ca. 1963. Collection Amistad Research Centre, New Orleans.

This sequence of ideas and practices—Reinhardt, Taylor, Brodzky, Tambellini—points to the richness of the historical crux inscribed in artscanada’s 1967 “black issue.” We find there a crossing of the colour line, one which exposes not only the whiteness of the 1960s art industry (a familiar history of exclusion), but also its interraciality. Multimedia practices like those of Tambellini and Warhol were part of a postmodern art scene that not only included many artists and musicians of colour, but was also fuelled by a complex politics of race: a dream of integration born of an interracial bohemia, as well as of the pressure exerted on this dream by Black cultural nationalism.

This historical crux marks both a critique of received art histories and a space for new ones. The Taylor/Tambellini intersection here is crucial. Tambellini’s performance, like Taylor’s own work at the time, was textured by a set of improvisatory interactions, as poet and dancer met in a flash of light, or a projected slide change responded to the movement of an audience member. These moments of intimacy occurred not between predetermined “subjects” (which, as Fanon tells us, are always silently white), but rather as flashes of spontaneous becoming between creative forces. Such encounters, which emerge from the history of African American improvised music, gave expression to a disordering force—what Fred Moten calls “blackness”—that was the condition of possibility for Tambellini’s metaphysics and Taylor’s music, as well as the Black art and politics of the Umbra group. The artscanada roundtable gives us a glimpse of the expansive field of such practices.

Aldo Tambellini, Black Zero, 1968. Performance score. Courtesy Aldo Tambellini Foundation.

Aldo Tambellini, Black Zero, 1968. Performance score. Courtesy Aldo Tambellini Foundation.