“It has been a very frustrating dialogue with them,” artist, curator and rape survivor Jaishri Abichandani tells me over the phone in late July. She’s discussing her experience with the Royal Ontario Museum. “I’ve seen them wanting to acknowledge my story while making me invisible.”

Here is Abichandani’s story as written in her diary, decades ago, and shared with close friends around the same time: in the mid-1990s, at the age of 25, she met photographer Raghubir Singh, who was then in his 50s. She went on a trip with him, agreeing to be his photo assistant. He harassed, assaulted and raped her.

In 1999, Singh died. In October 2017, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York debuted “Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs,” a show that has since toured to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. A few days after the opening at the Met, Abichandani, who is based in Brooklyn, went public on a New York–area radio show. Then, in December 2017, she and a group of supporters brought that message to the sidewalks outside the Met Breuer. She held a red and black sign that read “I survived Raghubir Singh…#MeToo” and many others joined her with signs that read “Me Too.”

“When I came out with this story, I was contacted by dozens of other women who were coming out with their own stories” of being sexually assaulted, says Abichandani. And, as artists, “none of us have any recourse…we do not have an HR department…we don’t even have a place to approach such things.”

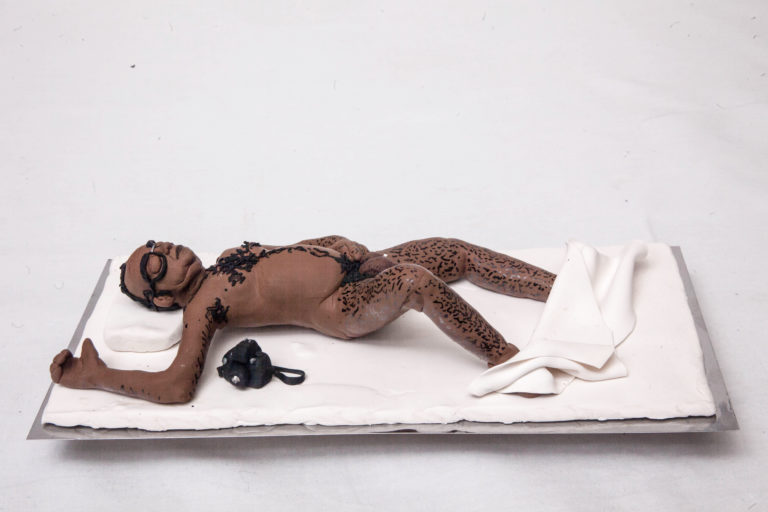

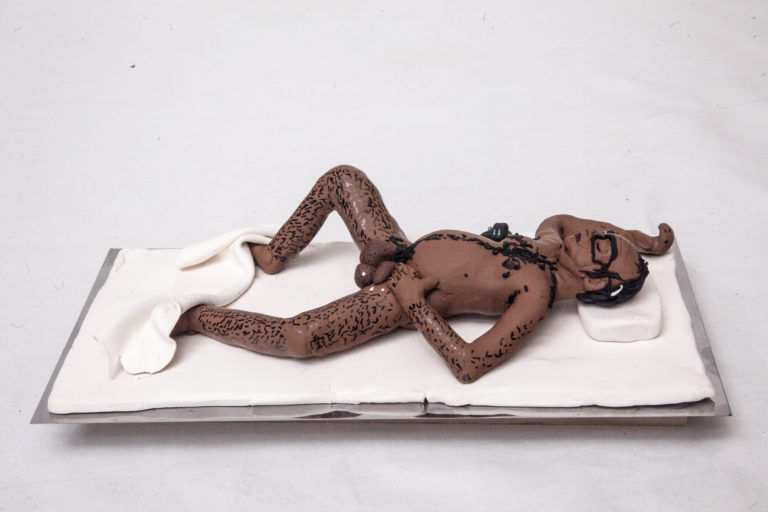

Abichandani began talking with curators at the Royal Ontario Museum after that protest, and she was hopeful for a positive outcome. After all, no other museums hosting “Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs” had asked to discuss her experience with Singh, and none had created a parallel #MeToo program and exhibition as a result. Abichandani wanted the ROM’s exhibition, “#MeToo & the Arts,” to include one of the letterpress signs from the December protest, as well as a small sculpture she created, which shows a man lying naked under splayed sheets, a camera at his side. She also wanted to include a New York protest photo she’d selected and, recognizing that many other people working in the arts have experienced abuse, rape and sexual assault, Abichandani suggested that at least some of the space booked for the Singh exhibition be given over to works by women and survivor artists.

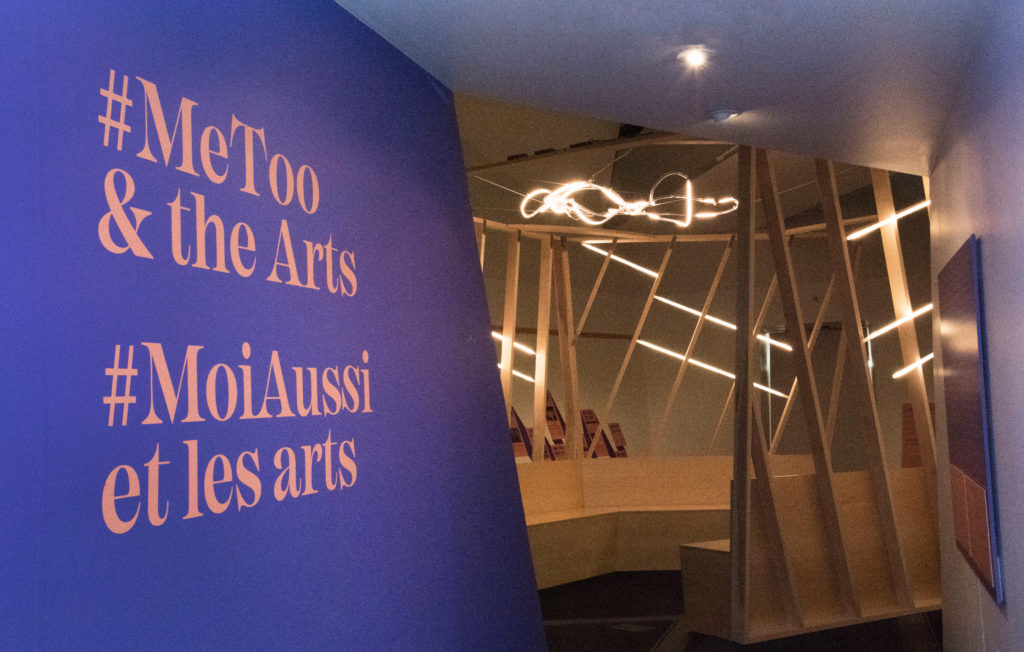

But the ROM’s answer to exhibiting the objects that Abichandani felt spoke most strongly to her own survivor experience was no. The ROM also rejected Abichandani’s suggestion of a survivor exhibition and downplayed connections between the two exhibitions. In “#MeToo & the Arts,” one of the mentions of Singh’s show at the ROM is literally in finer print, while in the Raghubir Singh exhibition, there is zero mention of the #MeToo program, let alone Abichandani’s allegations. What links the two exhibitions is minimal: a medium-size, purple sign outside the two entrances to the Singh exhibition simply states, “#MeToo & The Arts: Ground Floor.”

What’s more, the ROM’s “#MeToo & the Arts” public program involves a series of events, including a panel called Is the Future Female? and another on feminism, misogyny and sexual violence in the arts. Yet Jaishri Abichandani—whose rape and disclosure prompted the ROM to initiate its #MeToo program overall—was not invited to be take part in any of their events.

“I’m left in a kind of strange, vulnerable, dissatisfied, dissociated place with the exhibition,” says Abichandani over the phone. “I feel like they have managed to erase me while acknowledging the story in the most favourable way possible.”

As an arts journalist, I too am left surprised and disappointed at the extent to which the ROM—a widely respected institution which just had its highest-attendance year ever—has handled this situation. I’m upset about the way it has distanced Abichandani from the very exhibition her own experience prompted. It’s clear both from this and other instances that museums have a lot to learn about dealing with sexual assault and its survivors. Until that learning happens—on the part of museum management, administrators and CEOs, curators, writers and educators—many survivors are being put at risk of further harm in the process.

“Under patriarchy we get any response and we are supposed to be grateful for it, when we all know the situation demands a lot more than that,” Abichandani says. “I’m a survivor, and minimizing my experience just makes me feel invisible again.”

A view of the entrance to “#MeToo & the Arts” at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Photo: Wanda Dobrowlanski.

A view of the entrance to “#MeToo & the Arts” at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Photo: Wanda Dobrowlanski.

Jaishri Abichandani wanted the Royal Ontario Museum to include this sculpture in its exhibition on “#MeToo & the Arts.” The ROM said no.

Jaishri Abichandani wanted the Royal Ontario Museum to include this sculpture in its exhibition on “#MeToo & the Arts.” The ROM said no.

Another view of the same small sculpture.

Another view of the same small sculpture.

Though ROM press releases state that "#MeToo & the Arts" was prompted by "Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs," that link is not as strongly drawn in the spaces of the museum itself. Outside the Singh exhibition, a sign for the linked exhibition is simply placed nearby. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Though ROM press releases state that "#MeToo & the Arts" was prompted by "Modernism on the Ganges: Raghubir Singh Photographs," that link is not as strongly drawn in the spaces of the museum itself. Outside the Singh exhibition, a sign for the linked exhibition is simply placed nearby. Photo: Leah Sandals.

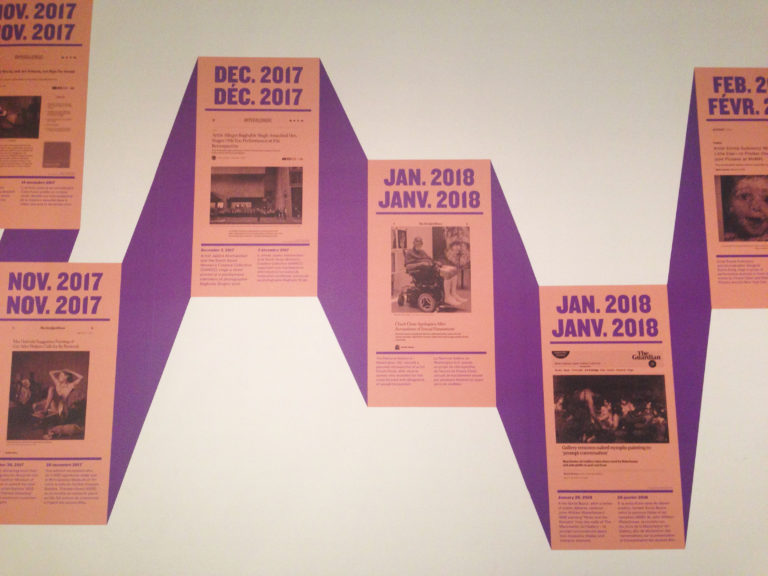

One of the main storytelling devices in the Royal Ontario Museum’s “#MeToo and the Arts” exhibition is a media clipping timeline. But while the timeline includes controversy related to the “Modernism on the Ganges” exhibition in New York, it does not include clippings on similar coverage for the show's arrival in Toronto.

One of the main storytelling devices in the Royal Ontario Museum’s “#MeToo and the Arts” exhibition is a media clipping timeline. But while the timeline includes controversy related to the “Modernism on the Ganges” exhibition in New York, it does not include clippings on similar coverage for the show's arrival in Toronto.

Exterior view of the Gardiner Museum. Photo: Antonio Tan.

Exterior view of the Gardiner Museum. Photo: Antonio Tan.

At the beginning of each session of Panic in the Labyrinth at the Gardiner Museum this summer, artist Annie Wong directed the performers to make a public dedication to Lucy DeCoutere, Linda Christina Redgrave and S.D., the women who survived the Jian Ghomeshi trial. Wong disagrees with the Gardiner's decision to book Ghomeshi's lawyer, Marie Henein, for a fundraising talk in September. Photo: Facebook.

At the beginning of each session of Panic in the Labyrinth at the Gardiner Museum this summer, artist Annie Wong directed the performers to make a public dedication to Lucy DeCoutere, Linda Christina Redgrave and S.D., the women who survived the Jian Ghomeshi trial. Wong disagrees with the Gardiner's decision to book Ghomeshi's lawyer, Marie Henein, for a fundraising talk in September. Photo: Facebook.

An installation view of "20 Minutes of Action" at Centre[3] in Hamilton. Photo: Andrew Butkevicius.

An installation view of "20 Minutes of Action" at Centre[3] in Hamilton. Photo: Andrew Butkevicius.

During its trial run in July 2016, Sexual Assault: The Roadshow, a travelling gallery, was installed in Toronto’s Scadding Court Community Centre. The words on the container read "Sexual Assault The Roadshow" and "It's Never OK." Photo: Leah Sandals

During its trial run in July 2016, Sexual Assault: The Roadshow, a travelling gallery, was installed in Toronto’s Scadding Court Community Centre. The words on the container read "Sexual Assault The Roadshow" and "It's Never OK." Photo: Leah Sandals