Drawing rooms are distinct from their later iteration, the living room, in that they are not for living but for retreating from life—the name is a shortening, but not by much, of the term “withdrawing room.” In the waning days of a summer heatwave, Marina Roy, the Vancouver-based artist, writer and educator, invited me to her plant-lined living room on an equally leafy street.

On the wall of Roy’s living room hung an oil painting, the artist’s own, part of her 2005–6 series Presidential Suites, which depicts woozy, surreal interiors—the imagined drawing rooms of famous leaders like Castro and Nixon, all inspired by watercolours of 18th- and 19th-century interiors. In one, Queen Victoria greets the day, seated in front of gilded cages full of pigs; in another, Margaret Thatcher bobsleds towards an enormous fireplace. Presidential Suites are drawing rooms at their peak—the missing link between public and private life. Roy shows them as antechambers between socialization and pure id, as mudrooms of the mind.

“I think that series is trying to combine ideas around power, because it is all presidential power figures—and then somehow trying to reveal something about…the invisible nasty or kind of erotic underside that seeps out of the walls in a room,” Roy told me.

I had the thought, long before meeting Roy or glimpsing her own living room, that her practice inhabited this realm between politesse and instinct. Call them drawing rooms or living ones, interiors are easy metaphors for the chambers of the mind, and Roy likes them with the windows flung open—whether in her 2009 installation Totem & Taboo, which presents the bookshelf as a kind of psychosexual study, or the 1993 bronze Bread, which commemorates domestic failure as public-facing sculpture.

“Because I am not rationalizing things as I do them,” she says, “there is an undercurrent of how power and desire comes through in weird, encyclopedic images.”

Cover for Marina Roy’s 2001 book sign after the x. Courtesy the artist.

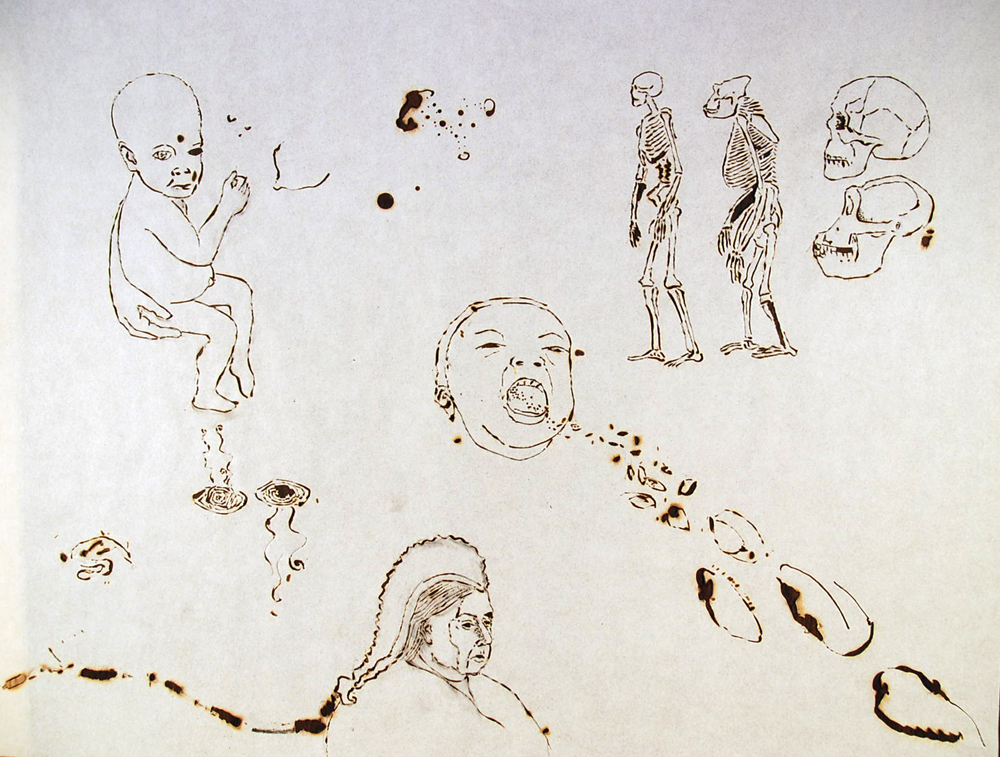

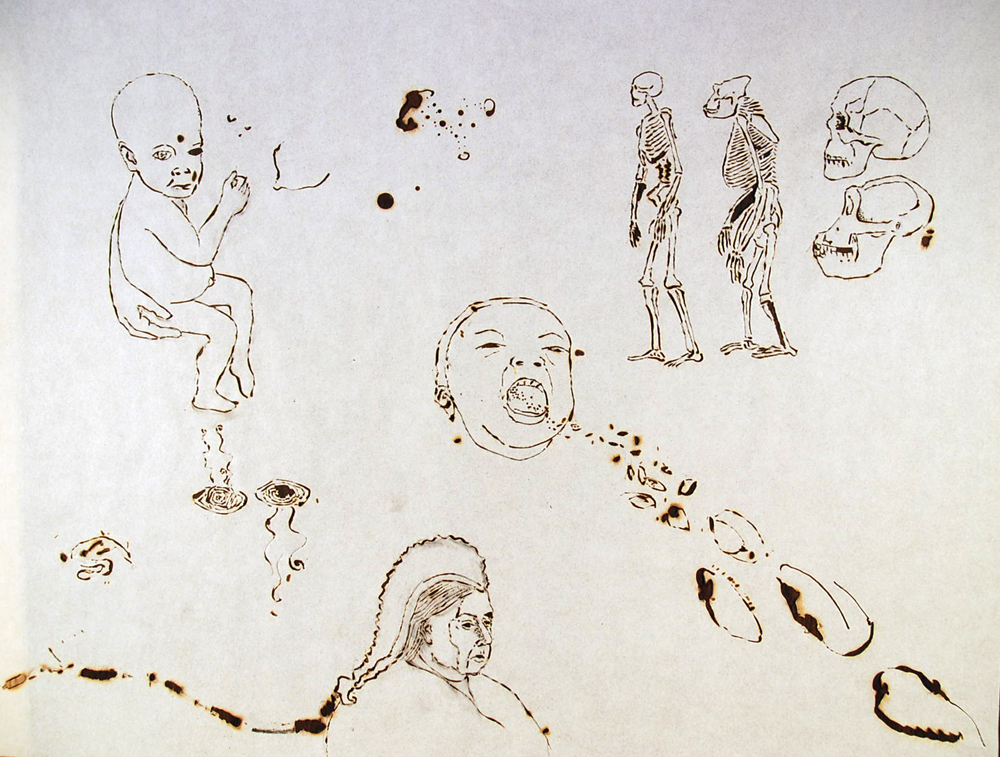

A spread from Marina Roy’s 2001 book sign after the x. Courtesy the artist.

A spread from Marina Roy’s 2001 book sign after the x. Courtesy the artist.

In Roy’s real-life living room, we ate blueberries from a small bowl and exchanged thoughts on apocalypse, hedonism and navigating the world. A pot of pistachio-green paint stood on the table like a vase of melted flowers. Disintegrating organic matter, and that particular green, also feature in her much-praised 2017 series Dirty Clouds, selections from which were shown earlier this year at Emily Carr University.

When we met, I’d just finished reading Roy’s 2001 book sign after the x. Where Dirty Clouds takes on antimatter and the universe, sign after the x is structured as a different type of cosmos: like a conversation at dawn, the book operates in concentric circles around its subject, which in this case is the third-last letter of the Roman alphabet. All books begin with a letter and Roy takes this fact to witty extremes, beginning, ending and centring her book around the varied meanings of the letter x. The book works like an abbreviated encyclopedia, bringing together disparate things, for instance Malcolm X and the Coleridge poem “Kubla Khan” that famously begins “In Xanadu…” The human desire to look for connection runs wild.

In sign after the x____ , about the most cypher-like letter, the act of grouping creates both coincidences and chasms. The blank spaces, gaps in knowledge or limitations of the form, become charged with poeticism and meaning. “When I wrote the book, it was like there was this void at the centre,” Roy says, “and I was trying to get to that philosophical stone.”

Roy is interested in classification and taxonomy—she draws unanswerable rebus puzzles that look like deranged encyclopedias (one work from her Rebus series looks like a hugely inappropriate children’s picture book), and she spoke to me of collecting and sorting words according to letter as a child—but the vacuums that underscore knowledge are what she really plays with. Much of sign after the x____ is made up of lists, a litany of x-words that reveal the impossibility of comprehensiveness. Roy is drawn, uneasily, to these blank spaces in human jurisdiction, what you might call the unknown, but is perhaps better termed unknowable.

X commonly stands in for unknowns—in algebra, philosophy and psychoanalysis—and Roy quickly shifts the search for specific unknowns to a grander plane: “At the time, I was thinking what is that mysterious x that drives us…it is the unknown thing that drives us without us knowing why, that kind of seething sexuality or violence or inability to understand oneself and understand what is at the root of culture.”

Of course, a single letter is not a key to the attic of Western culture, but the act of exploring within strict limitations calls for decisive moves—exclusions that, like the choice of when to end a piece of music, create powerful silences. Roy’s lists sing with the presence of everything left behind, everything that is not known.

Marina Roy, Your Kingdom to Command, 2016. Mural with latex paint, bitumen, red-iron oxide, shellac and tar on plywood, with tree stumps and fountain. 2.56 x 6.09 metres overall. Courtesy the artist/Vancouver Art Gallery.

Marina Roy, Your Kingdom to Command (detail), 2016. Installation at Offsite, Vancouver Art Gallery, June 2 to October 10, 2016. Mural of latex paint, bitumen, red-iron oxide, shellac, and tar on plywood; also stumps/fountain; 84 × 20 × 20 feet. Courtesy the artist.

Marina Roy, Your Kingdom to Command (detail), 2016. Installation at Offsite, Vancouver Art Gallery, June 2 to October 10, 2016. Mural of latex paint, bitumen, red-iron oxide, shellac, and tar on plywood; also stumps/fountain; 84 × 20 × 20 feet. Courtesy the artist.

Though often roaming interiors and unknowns, Roy’s artworks have found a positive and concrete public profile in Vancouver. Her willingness to engage with uncomfortable, vulnerable and sometimes personal gestures and themes—as in 2009’s The Human-Animal Divide video, where she performs a philosophical lecture with increasingly animalistic behaviour throughout—create an easy camaraderie with her audience.

Yet Roy’s impact in the city where she lives and teaches is also the result of concentrated acts of kindness and a desire to build communities. Katherine Dennis, a local curator and former student of Roy’s, describes her as “perpetually supportive and without pretension” and remembers her critical theory classes at UBC as an indispensable primer in “think[ing] critically about art and how we view and engage with artworks within a social and political context.”

The social context of art-making comes up repeatedly when people discuss Roy’s position in Vancouver—Dennis says that, to her, “Marina has demonstrated the importance of moving beyond the institutional walls and taking part in the community.” Dealer Wil Aballe (who has exhibited the artist but does not represent her) says, “I always thought of Marina as being a central figure, being someone who is an educator at UBC, and who, through many years, has been a mentor to artists who studied there and have since matured into themselves.” He cites Abbas Akhavan, whose explorations of domesticity and hostility align with Roy’s, as one such former student. (This coming weekend, Akhavan will be in a public dialogue at Toronto’s Power Plant with Roy and curator Nabila Abdel Nabi.)

On the bus (delayed) I took to meet Roy, I was rerouted around a mural festival. In it, art-making was made exceedingly public—and the art produced was made subordinate to urban structures, in this case flat, unobstructed exterior walls. Years ago, I led a visiting friend through another part of town, a route that took us past Roy’s first foray into public art.

That public piece, Your Kingdom to Command, occupied the Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite space in downtown Vancouver in summer and fall of 2016. The installation combined a tree-stump fountain with a 25-metre mural of small, amoeba-like forms, as well as shapes of plants and flowers, painted in latex and bitumen.

Amid the glass towers of Vancouver’s financial district (Offsite sits beside the Shangri-La building, BC’s tallest) the forms of Roy’s mural, reminiscent of fungi, and the salvaged wood centrepiece were like a scream on a silent train. They did not complement the urban landscape, but rather pierced it.

To me, Roy mentioned how new materialist philosophy impressed her, making it possible “to look at humans as future fossils and even fossil fuels.” It also made her reflect on “the way we treat everything in life as not connected to us. Somehow we can do this to the world because we don’t see the meshwork right.”

Again, a sense of a listing, classification, matrix or litany strikes me in considering this work. When describing the mural’s painted forms, which appear in flattened rows like artifacts in a natural history museum, Roy has called them “the ghosts of the fauna and flora and everything else that makes the asphalt over millions and millions of years, all this dead matter creating this liquid that we burnt up and used in a century.”

The micro-organisms Roy paints in her mural are horizontal and therefore equal, and she chooses to present them as a dirge of dead or almost lost things surrounding a painted black pyramid. The pyramid seems a vacuum into which these organisms will soon disappear; the black shapes can also be read as asphalt. The work’s position next to a busy road, in the shadow of capitalist monuments, is poignant and almost knowingly futile. The world as we know it is slowly dying; we list what is lost. It’s a grand and gothic gesture. Yet what is more quotidian, more daily and more domestic, than a list?

Marina Roy, Sleeper (still), 2004. Cel & collage animation. Sound by Graham Meisner. Courtesy the artist.

Marina Roy, Sleeper (still), 2004. Cel & collage animation. Sound by Graham Meisner. Courtesy the artist.

Marina Roy, Sleeper (still), 2004. Cel & collage animation. Sound by Graham Meisner. Courtesy the artist.

Along with a distinctly 18th-century interest in taxonomies—taxonomies being a kind of systematic list-creation effort—Roy’s work often employs art-historical tropes of that era, and of the 19th century too. It’s as if she questions the underpinnings of monolithic Western culture by using the imagery of those cultures’ heydays: take the ornate fireplaces and crown mouldings that enshrine the 20th-century political leaders in Presidential Suites, for instance.

In public talks, Roy has spoken of creating her distinctive visual language through accumulating an archive of images—virtual and literal folders of imagery she refers to like a thesaurus. Even across mediums as varied as animation, painting and sculpture, the trappings of “high culture”—opulent interiors, old-fashioned costumes and talismanic, quasi-religious symbols—are contrasted with anthropomorphic animals, demonic figures and queasily fungal forms. The intersections and lapses between related imagery glow with meaning.

The charged, indefinite space Roy works with could be called the unconscious, and there is a dreamlike surge to her work. Occasionally she engages literally with the state of unconsciousness, as in the 2004 animation Sleeper, which seems to depict a dream as it flits from scene to scene: birds roosted eerily in a tree, a fox running towards a naked person on a swing, an egg rolling underground through old bones.

Of dreams, Roy is both intrigued and wary: “I always thought it was very boring to hear peoples’ dreams,” she says, “but I have always been interested in the inner theatre and I think that somehow that gets distilled into the work.” It’s a process that occasionally surprises the artist herself; in the Presidential Suites series, Margaret Thatcher is painted alongside a mysterious, seated woman working on a puzzle, a woman Roy unconsciously painted as her own mother. Roy has also spoken of Rebus drawings operating “how you might be describing the figures that are unfolding in a dream…as you pronounce the dream, certain elements of the latent meaning come through.”

The machinations of language, the ways it can conceal desire or make it startlingly clear—Freudian-style, perhaps—are ever-present, and ever-questioned in Roy’s work. Sometimes, this engagement with language can be almost comically foregrounded—as in the 2000–1 series Thumbsketch Collection, which uses the cut edges of paperbacks as supports for lewd doodles that both compliment the books and besmirch them, too. There is a conspiratorial tone to these pieces—finding notes in the margins of books is always a voyeuristic thrill, which Roy exploits and amplifies with her drawings.

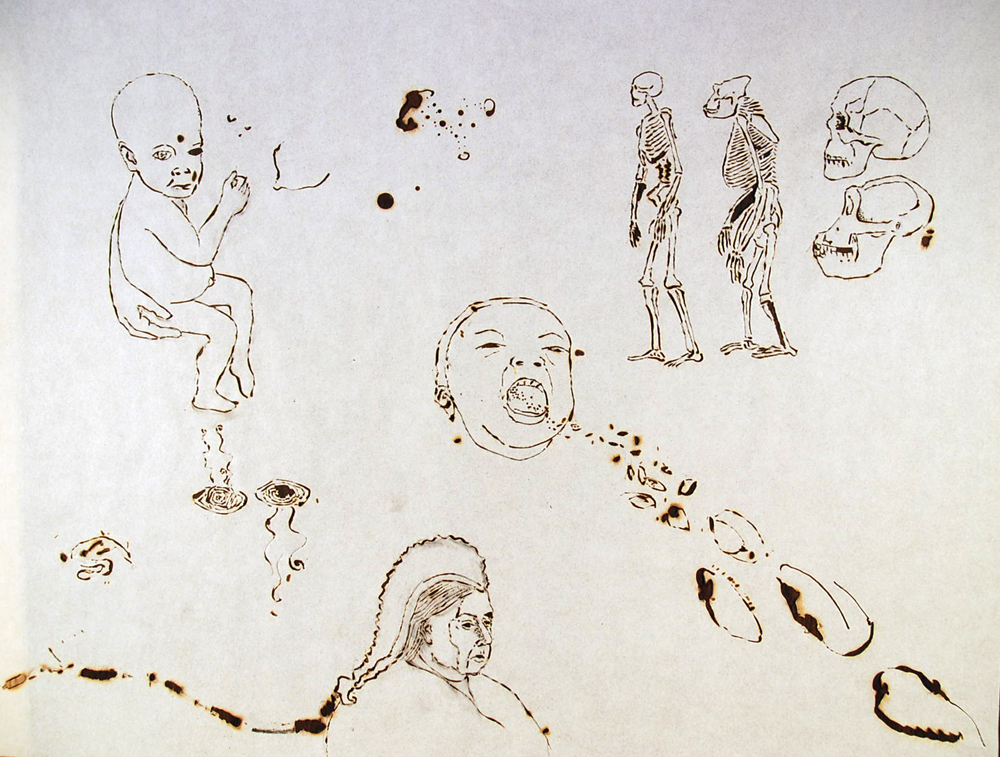

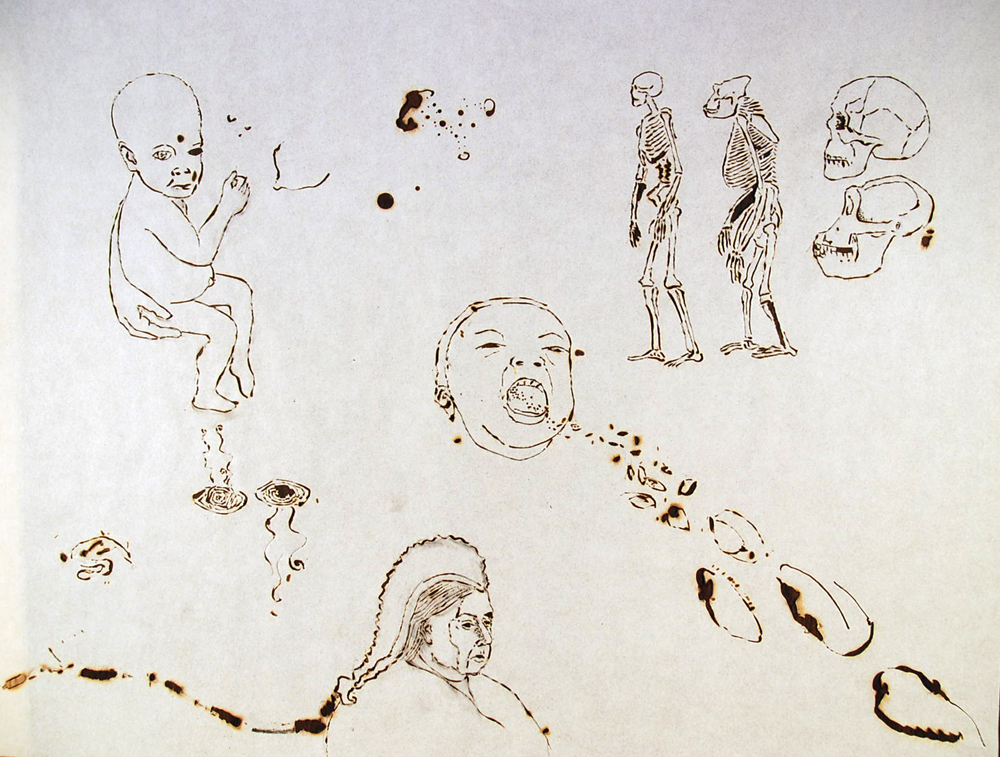

Roy’s Burn Drawings, simple images literally burned into paper during the early-to-mid-2000s, are experiments in material practice with unexpected emotional clout. We say certain details—the words of a lover or the scent of a decisive moment—are “burned” into our memories. Roy’s engagement with this idea is more than nostalgic and appears in some way or another throughout much of her work; she asks how unshakable memories, both cultural and personal, define present realities.

Marina Roy, Human, 2010. Burnt paper, 22 x 30 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Marina Roy, Dad Dream, 2010. Diptych on burnt paper, 22 x 30 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Marina Roy, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man from The Thumbsketch Collection, 2000. Pencil and coloured ink on paperback, approx. 6.5 × 4.5 inches.

Marina Roy, Lost Illusions from The Thumbsketch Collection, 2000. Pencil and pencil crayon on paperback, approx. 6.5 × 4.5 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Perhaps the most distinctive element of Roy’s practice is its bawdy, folk-art inflected humor, which she pins to her French-Canadian upbringing, but I see as a winsome act of resistance. This feverish eroticism can be violent, animalistic and playful, often all at once. Sexuality here is a way to distill various biological and philosophical concerns into a pithy, very funny, droplet. Taboo and excess in Roy’s work functions as a method of debasement—knocking humans down a peg in order to comment on the animalistic drives that are at the root of so much human endeavour.

This approach to human nature is at its most cheeky and unforgettable in a series of paintings Roy produced from 2003 to 2009. Called Spill Paintings, these pieces work by using a mirror and a piece of clear glass to create a series of semi-obscured paintings overlaid with splotches of opaque paint. The human and animal figures are nightmarish, puerile and strangely sweet; a bikini-clad woman inflates a sleeping man’s penis like an air mattress, two horses fuck and a city burns—there appears to be some torture. Viewers have to sidle along the pieces and peer behind the splotches to catch a glimpse of what’s happening, it’s like watching a Rorschach test coalesce into its own debauched interpretation.

Sublimated preoccupations and desires are the crux of Roy’s practice; her subject is most often the culture, but occasionally the artist herself becomes wrapped up in her skewering of civilization.

“I don’t like the work and I don’t feel feel intense or good enough if the work doesn’t have an element of vulnerability,” she says. “I think it has to be monstrous to be good.” “Discovering the monstrous within the human,” she adds later, is a metaphorical exercise in adopting a different, more liberated point of view: “to become the animal, which is more at peace with itself.”

Marina Roy, King Faisal from the Presidential Suites series, 2006. Oil and encaustic on wood panel, 12 × 18 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Marina Roy, King Faisal from the Presidential Suites series, 2006. Oil and encaustic on wood panel, 12 × 18 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Roy’s most winning ability might be finding monsters where they are obscured, or hidden. Back in Roy’s living room on that too-hot summer day, over blueberries and conversation, I kept looking at the Presidential Suites as a gloss for Roy’s practice. In the drawing rooms of the rich, she sees seats of power and therefore of corruption; but Roy’s scope is much larger.

The psychoanalytic undercurrents to Roy’s paintings—and drawings, and books and videos—she says, create “a narrative of how civilization has infiltrated the family.” Living rooms are also called family rooms, and the sites of family ritual are no less compromised than their ceremonial counterparts. Nothing is inanimate; even the walls of a room radiate with unacknowledged complications, what Roy calls the “invisible, nasty or kind of erotic underside.”

As for what’s next, Roy has written a book about another letter: Q. “There is this weird relationship that I have with knowledge where I can never know everything,” Roy says. “But I kind of try to figure out how I can enjoy studying things by going down my own path.”

I left Roy’s apartment and our conversation with my own lists—books to read, performances to catch, digital aphorisms to remember. The listing continued; in drafting this piece, I tried listing famous living rooms and found that again, cataloging revealed underlying principles. All my examples were terrifying: Laura Palmer’s living room in the original Twin Peaks, overwhelmed by the presence of another Laura (Ashley) and made untidy by evil incarnate. I remembered Michael Haneke’s Funny Games and its very beige, very clean living room that would not remain so. I thought, especially, of the drawing room of Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel. The characters in that film studiously avoid the indelicate, until a tidal wave of vulgarity sweeps them away.

Roy’s work exists on the crest of just such a wave—at the absurd convergence of desire and socialization, where the things that protect us can also menace. It reminds me of the living rooms in some of her Suites paintings, rooms that block out the elements with ornate pillows and cushy chaise lounges, but seethe, still, with discomfort.

Marina Roy, Nixon from the Presidential Suites series, 2005. Oil on panel, 12 × 18 inches. Courtesy the artist.

Marina Roy, Nixon from the Presidential Suites series, 2005. Oil on panel, 12 × 18 inches. Courtesy the artist.