Kosisochukwu Nnebe, I want you to know that I am hiding something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable (detail), 2019. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, I want you to know that I am hiding something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable (detail), 2019. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo: Justin Wonnacott.

Kosisochukwu Nnebe

Kosisochukwu Nnebe is active both as an artist and curator. Based in Ottawa and trained as an economist and policy analyst, she addresses public policy issues through visual arts and media. Her exhibition “They Forgot That We Were Seeds,” at the Carleton University Art Gallery earlier this year, brought together Black and Indigenous artists who work with food to create a “counter-archive” of labour, displacement and sovereignty. “I’ve been going to Toronto and meeting artists and that’s been really important,” Nnebe says, “but I think it is also important to establish art spaces [here] so that people don’t need to make that journey in order to be seen or represented.” Nnebe’s artistic practice explores the process of racialization, specifically how Black bodies are allowed to move through the world. A core component of her recent installation I want you to know that I am hiding something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable (2019) consists, in part, of photographic images of arms and legs suspended from the gallery ceiling. Informed by Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, Nnebe wanted to simultaneously illustrate the violence inherent to the act of undoing that occurs when race is projected onto an individual, and the understanding that “Blackness is larger than life and cannot be contained.” It’s also a prompt for viewers to be aware of their own presence and the relationship of their bodies to the gallery: “What does it mean to create a space where people can feel safe? What does it mean to create a space for meditation and contemplation? I want people to experience my work and to increase their capacity for humanity.”

Letitia Fraser, Virtuous Woman, 2019. Oil on canvas, 1.37 x 1.21 metres.

Letitia Fraser, Virtuous Woman, 2019. Oil on canvas, 1.37 x 1.21 metres.

Letitia Fraser

Currently based in Halifax, Letitia Fraser has roots in North Preston, in rural Nova Scotia, which is home to the oldest and largest Black community in Canada. In her practice, she often paints atop squares of fabric that she has stitched together in homage to her grandmother, who was an avid quilter. This work also references the prevalent quilt-making tradition of North Preston, which parallels that of the Gee’s Bend quilters of Alabama. What drives Fraser’s practice is a desire to convey the depth and breadth of the cultural life that exists in North Preston. “There are a lot of Black communities that people don’t necessarily know about. People from away don’t know how deep the history is,” she says. “My goal is to let people know that we exist…and to try to preserve our history and culture.” Fraser gives the people of her community “a chance to see themselves” by depicting them in her artwork. Her recent solo exhibition at the MSVU Art Gallery served as an ode to her family, featuring portraits of her mother and aunt (the latter of whom is depicted braiding Fraser’s cousin’s hair) painted on quilts. The central work in the exhibition was a portrait on canvas of her great-aunt Lillian Downey, who helped raise her. In honour of this relationship, Fraser wants to begin to focus on working with elders in the community. She has also started to explore rug hooking: “I want my work to evolve, and the way to do that is to experiment with other forms of art and subject matter. But because I am Black, that will always be a part of my practice.”

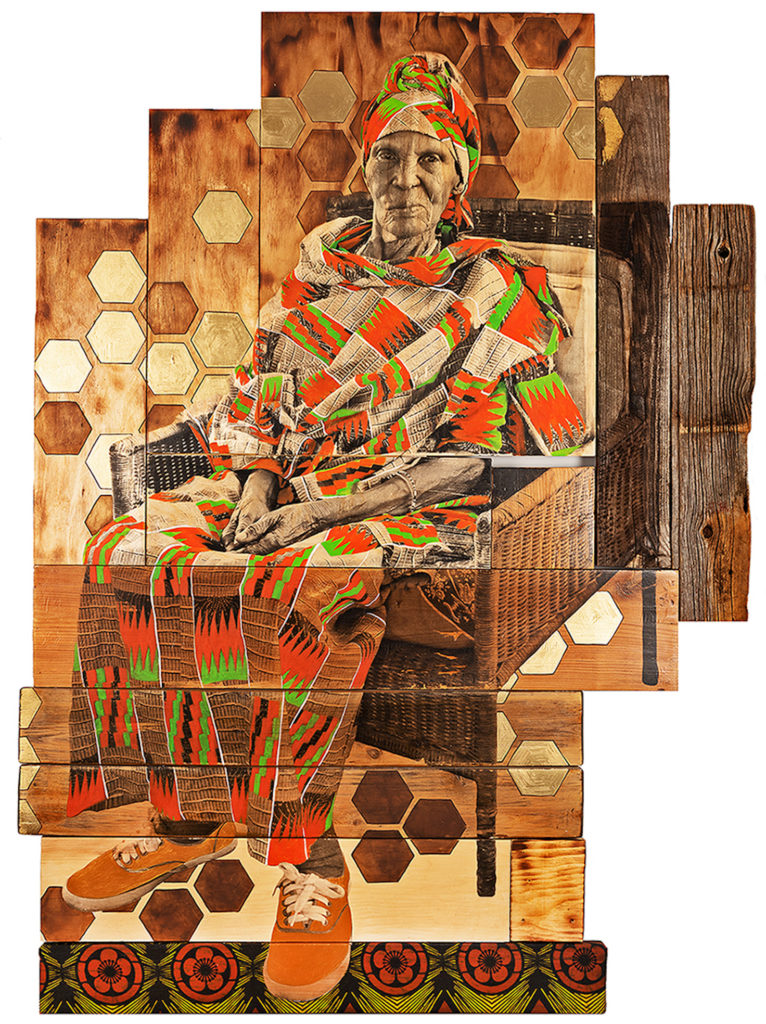

Shanna Strauss, Bee Keeper, 2019. Photo transfer, acrylic, fabric and woodburning on found wood, 1.34 m x 91.4 cm. Photo: Catherine Quinn.

Shanna Strauss, Bee Keeper, 2019. Photo transfer, acrylic, fabric and woodburning on found wood, 1.34 m x 91.4 cm. Photo: Catherine Quinn.

Shanna Strauss

Based in Montreal, mixed-media artist Shanna Strauss uses found wood, transformed by her process of burning and carving, as the support for portraits—often photo transfers of people she knows combined with elements of painting, collage, fabric and sometimes paper. “I’ve always been intrigued by wood,” Strauss explains. “It’s a magical material: it’s heavy, but it floats.” Much of the artist’s practice honours women and their labour, as in her murals Mary Two-Axe Earley and Ellen Gabriel (2017), which eponymously commemorates the work of Indigenous activists, and Difference is Power (2019), made in collaboration with her partner, artist Jessica Sabogal, to pay tribute to the women of colour who have contributed to the field of nursing. Strauss’s Memory Keepers (2017) stems from an ongoing series that examines oral traditions and family legacies. “Blood memory is a profound component of my work,” she says. Memory Keepers revolves around an ancestor named Leti—a fierce woman warrior who mobilized her community in Tanzania to defeat German colonizers. Strauss woodburned honeycombs around the figure of Leti to memorialize her grandmother, a beekeeper, who told Strauss that Leti used bees to defeat the Germans. Strauss’s grandmother also shared that first daughters in their Nyaturu tribe are often given the name Leti. For Strauss, this generational knowledge adds yet another layer to the work: “Passing on names and storytelling are the ways we remember those who came before us and important historical events. In this body of work, I push back against Eurocentric standards that discredit oral traditions…. Storytelling is not just a critical part of my family’s legacy; it is for my cultural legacy as well.”

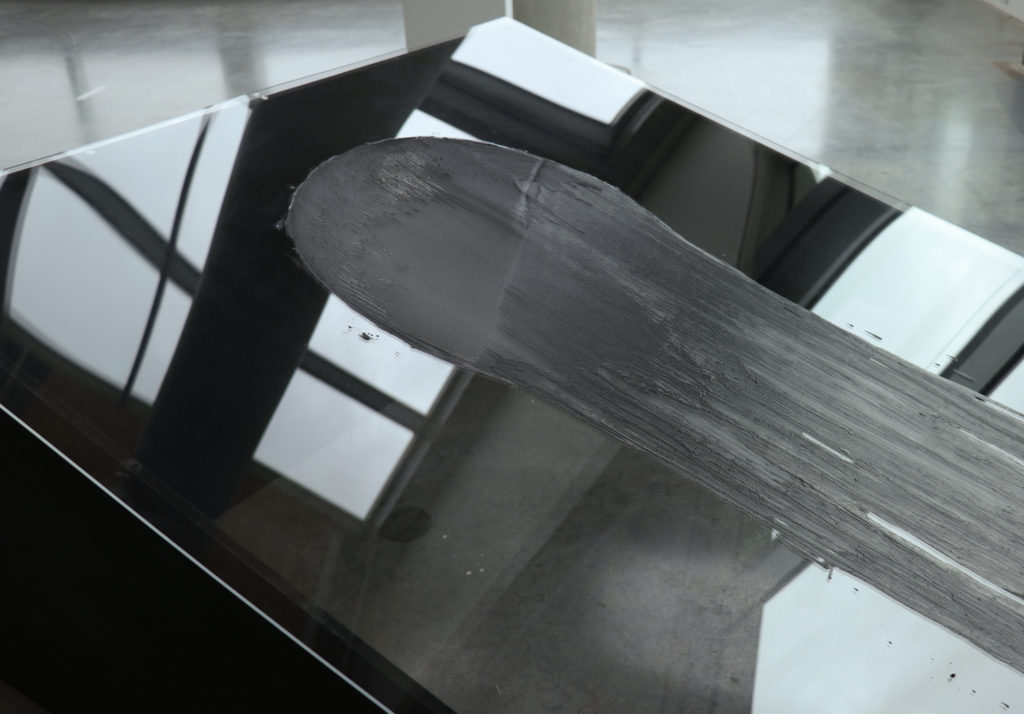

Rebecca Bair, Collaboration With The Sun (detail), 2019. Shea butter and charcoal drawing on Plexiglas, 1.82 x 1.21 metres.

Rebecca Bair, Collaboration With The Sun (detail), 2019. Shea butter and charcoal drawing on Plexiglas, 1.82 x 1.21 metres.

Rebecca Bair

Though a photographer by training, Rebecca Bair states that she is “100 per cent a multidisciplinary artist.” Based in Vancouver, where she recently completed an MFA at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, Bair explores various forms of mark-making in her work, often using unorthodox materials. “My practice right now is about abstraction and non-figuration,” she says, “and how these can be used as methods for representing the Black body, particularly the Black body on Turtle Island. I use this language because I am trying to decolonize my mind and my tongue.” In Collaboration With The Sun (2019), a piece Bair claims was “probably my favourite work to make” because of “the physicality of it,” the artist combines charcoal with shea butter to draw on Plexiglas. With a desire to trace existence with a substance she wears on her skin and in her hair, Bair mixed the materials to give her medium a darker hue, intending for it to reference the Black body but also concentrate the effects of sunlight. “The work was made in a window,” Bair explains. “As I drew with shea butter and charcoal, the sun would come and melt it…it was a ‘call and response’ between me and the sun. I think that this work carries this idea of Black plurality, Black change and Black expansiveness most directly, and is still changing to this day.”

Sobaz Benjamin.

Sobaz Benjamin.

Sobaz Benjamin

“It’s an odd practice; it’s unusual,” says artist Sobaz Benjamin, describing his work. “It’s industry- as well as community-based, and inspired by my desire to become a better storyteller.” Benjamin’s multifaceted approach to artmaking began in the late 1990s at York University. While completing a degree in film and video production, he worked as an instructor for Project ADVANCE, which uses assisted technologies to provide new students with tools to effectively engage with the university environment. After graduating from York, Benjamin settled in Halifax, working on a range of film projects, including the CBC documentary series Kids Across Canada, and directing the acclaimed NFB films Making It (2006) and Race Is a Four-Letter Word (2006). In 2007, Benjamin was asked by the then–executive director of correctional services at the Nova Scotia Department of Justice, Fred Honsberger, to make a film that was intended to “highlight the contributions of African Nova Scotians to the Atlantic region,” in reaction to the inordinate incarceration rates of African Nova Scotian men. He responded by creating In My Own Voice (iMOVe), an arts-based reintegration program informed by his experience with restorative justice and aimed at addressing systemic social issues. Working with those who have experienced various forms of social marginalization, iMOVe offers platforms for creative expression, such as Youth Now Radio; the theatre program Shout Out From the Inside; and Centreline Studios, a music and production studio located in Halifax’s Uniacke Square neighbourhood. The participants, who include formerly incarcerated people and marginalized youth, are instrumental in developing these programs. The key, Benjamin says, is to create “artwork that heals the individual, and by extension their families, through transforming the identities of their communities.”

Installation view of Afrocentric Artist Showcase, curated by Alexa Joy, at Aceartinc. as part of Nuit Noire, September 2017. Photo: Travis Ross Photography.

Installation view of Afrocentric Artist Showcase, curated by Alexa Joy, at Aceartinc. as part of Nuit Noire, September 2017. Photo: Travis Ross Photography.

Alexa Joy

For Alexa Joy, the founder and president of Black Space Winnipeg, the impetus for creating the organization began during her undergraduate studies in Human Rights and Conflict Resolution at the University of Winnipeg. Shocked that her program made no mention of the history of Black activism in Canada, Alexa Joy was determined to counter this: “I was passionate about my community and wanted to address the systemic erasure and discrimination that happens to Black folks in Manitoba.” Launched in 2016, Black Space Winnipeg started as a centre for advocacy and way to spark conversation about anti-Black racism in Canada. Alexa Joy initially held workshops geared toward education and awareness, then shifted her focus to supporting the efforts and practices of Black artists. She curated Nuit Noire, a program that highlights the work of Black artists in the city, in response to the lack of representation at Nuit Blanche in Winnipeg; it is now an annual component of the larger festival. She is also the festival director of the Afro Prairie Film Festival (co-presented with the Winnipeg Film Group), which features work from Black diasporic filmmakers. Recently accepted into a master’s program at the New School for Social Research in New York, Alexa Joy will examine links between colonization, white supremacy and the rise of hate in contemporary discourse, and the potential for curatorial and artistic disruption of white gallery spaces. She views this academic foray as a continuation of the advocacy and curatorial work she has focused on for the last several years: “I’m passionate about getting Black artists the tools they need in order to succeed. The support and exposure of Black artists will always be the foundation of my work.”

Concert performance by Dayo Bello, co-presented by Half A Concert and Black Artists Union, at Almost Half Studios in Toronto, March 2020. Photo: Filmon Yohannes.

Concert performance by Dayo Bello, co-presented by Half A Concert and Black Artists Union, at Almost Half Studios in Toronto, March 2020. Photo: Filmon Yohannes.

Black Artists Union

Toronto collective Black Artists Union (BAU) began when former member Nathan Olokun suggested that a number of emerging Black artists in the city who were showing individually should begin to exhibit together. Since its creation, the group has been mindful of maintaining an ethos of community engagement and collectivity, striving to build what founding member Timothy Yanick Hunter describes as “frameworks and networks to bring artists forward and share resources as a group” and ways to “use art as a platform to get the [Black] community involved.” The group’s first project, “Night Glow Fabric,” mounted at Will’s Gallery in December 2016, featured works by its seven founding members: Olokun, Hunter, Oreka James, Flimon Yohannes, Aaron Jones, Curtia Wright and Phillip Saunders. More exhibitions followed and, in 2018, BAU embarked on a year-long residency at Whippersnapper Gallery. Hunter, James, Jones and former member Destiny Grimm organized the residency and took over the space, staging a number of exhibitions and projects that explored how notions of Blackness shift between geographic regions and across generations and media. The collective has also organized youth art workshops at the Cedarbrae Branch of the Toronto Public Library, which touch on formal and thematic issues ranging from collage to food sustainability. As with all of their projects, the ultimate goal is to use art to move beyond the gallery space to open new dialogues and forge greater connections and understandings. “You are a representative of a community,” Hunter explains. “It’s one thing to have discussions in a gallery setting with people who are in agreement with you. How do you do something that is more impactful?”

Justine A. Chambers and Laurie Young, One hundred more, 2019. Performance at Sophiensaele Berlin, December 2019. Photo: Oliver Look.

Justine A. Chambers and Laurie Young, One hundred more, 2019. Performance at Sophiensaele Berlin, December 2019. Photo: Oliver Look.

Justine A. Chambers

Vancouver artist Justine A. Chambers arrived at her movement-based practice through dance. She creates works predicated on physical action that “doesn’t always manifest in performance but is centred on bodies, embodiment, movement and feelings.” Countering traditional experiences of performance that rely on passive spectatorship, Chambers makes environments that prioritize engagement, collaboration and empathy. “Everything that I make is about embodiment or movement,” she explains. “It is about bodies and our bodies together.” Chambers’s Family Dinner (2013–), a cumulative performance project based on her mother’s experience as the wife of a diplomat, is an embodied archive of eating that explores the social codes and physical gestures, such as toasting, serving and seating, that transpire within the context of a dinner party. Requiring several performers (including Chambers), in addition to invited guests, the work is an exercise fraught with intimacy and discomfort (“It’s always awkward eating dinner with people you don’t know,” she says). One hundred more (2019) is a recent performance with artist Laurie Young, and made in collaboration with Emese Csornai, Neda Sanai and Sarah Doucet, which Chambers describes as an “archive of personal gestures of resistance.” The work debuted in December in Berlin and was set to tour to venues in Montreal and Vancouver this year, but these performances were postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. At a time when isolation is being stressed as a means for survival, Chambers’s engaged practice seems almost incongruous. However, there is still space for the ethos behind her work. “With empathic choreography,” she says, “it could just be as simple as holding the door open for another person.”

Farihah Aliyah Shah, (from left) Untitled (Legs), Laden Hands and Untitled (Roots) (from the series Billie Said, ‘Strange Fruit’), 2017. Archival digital prints, 99 x 66 cm each.

Farihah Aliyah Shah, (from left) Untitled (Legs), Laden Hands and Untitled (Roots) (from the series Billie Said, ‘Strange Fruit’), 2017. Archival digital prints, 99 x 66 cm each.

Farihah Aliyah Shah

Farihah Aliyah Shah defines herself as a lens-based artist—working in photography, film and video—though her practice also incorporates other media, such as sound installation. The Bradford, Ontario, artist’s interest in photography grew from a fascination with her father’s 35 mm camera, and the directive that she learn the mechanisms of the instrument before being allowed to handle it. Once she became familiar with the camera, Shah began to explore the concept of tableau, informed by her training as a dancer. Her work investigates the colonial gaze, specifically by interrogating the ways identity is formed within the lens and history of imperialism. Shah is also interested in the idea of collective memory and how history affects individuals, as well as in notions of site and “what it means to have many places that we call home.” This last idea encapsulates the liminal space Shah occupies as someone who is both Canadian Guyanese and biracial (of Black West African and Indian descent). For an upcoming project, Shah plans to turn her attention to a collaborative piece with her mother. Using a Guyanese cookbook that Shah’s mother frequently references, the two will prepare dishes highlighting the confluence of Indigenous, Pan-African and Indian cuisine that forms the crux of Guyanese cooking. It’s work that shows how food creates community and engages cultural memory, while also embodying ways of sharing the table. “I see Guyana as a metaphorical space that parallels my own identity,” Shah explains. “It’s been colonized multiple times, and is ostracized by many spaces within South America…yet within it there is a space of rebellion and resistance. I am hoping that folks will come away from my work with a decolonized perspective.”

Kiera Boult, #TeamKiki (for institutional use only) (still), 2018. Video, 2 minutes, 30 seconds.

Kiera Boult, #TeamKiki (for institutional use only) (still), 2018. Video, 2 minutes, 30 seconds.

Kiera Boult

Toronto performance artist Kiera Boult uses popular culture and reality TV to interpret theory. By crossing humour with vernacular forms of queer aesthetics, Boult offers a velvet-gloved approach in her explorations of class, race and place. Boult arrived at OCAD University in 2011 with a painting portfolio, and was initially interested in collaging with paint. She then moved on to making transfers using newspaper and tape, but continued to encounter the ways the medium was limited as a platform for more insightful analysis. After viewing Martha Rosler’s iconic video work Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), Boult observed how performance could use straightforward strategies to deliver highly incisive commentary. She also began to see how reality programs such as RuPaul’s Drag Race and I Love New York offered platforms for performers of marginalized identities to position themselves. In response, Boult created Truth Booth (2013–19). A version of the project, called Truth Booth: Art is the New Steal: Appropriating the Hamilton Landscape, was staged at the monthly Art Crawl in Hamilton in 2016 , and sought to interrogate the city’s ongoing gentrification. Under the guise of her performance persona Kiki, the artist set up a portable pink booth and used elements of spectacle and flamboyance to disarm and entice passersby to participate in the project, regardless of the sarcastic “reads” that her character would bestow upon them. Despite the success of this persona/project, Boult is looking to retire Kiki because she feels the character is limited in terms of her ability to delve into more complex probings of race, class and gender: “I have a deep desire to retire Kiki…and find it hard to see this work as political. And if my work is not political, then I am just Drake.”