The math occurs because of the page—because the page is a grid, a map of coordinates. The message is also a number, a quantity of character spaces. There is no message without a container, no container without limits, no limits without quantification. It’s a realization that occurs over and over in the intertwined histories of visual art and poetry in modernity: writing not as expression but as confrontation with a limited schema or net, that site (cf. Mallarmé) of the writer’s shipwreck.

But I am not really interested in generalizations about media. Of greater interest to me are individuals, specifically their obsessions and solutions. How is it, for example, that two female artists, both born in 1941, one in Northern Germany, one on the east coast of the United States, both living in Manhattan in the late 1960s and participating in adjacent if not identical visual art communities, came to use sums and equations to manipulate the space of the page? Why did each determine that a style of quantification was a necessary component of her poetics? What can we learn from these sometimes inscrutable, personal mathematics, this mathematical prose?

Hanne Darboven, the German artist, was born in Rönneburg, outside of Hamburg, second daughter of three, to Cäsar Darboven, heir to and owner of the J.W. Darboven coffee roaster and general store (not to be confused with the J.J. Darboven coffee company, a better-known firm that has since expanded across Northern Europe). Hanne’s mother, Kirsten, was Danish. Her father was a successful contractor for the German military, supplying coffee to the army of the Third Reich. Later, there was an adolescence involving boarding schools and social dysfunction. Although Darboven had originally trained as a concert pianist, she entered art school, the Hochschule für bildende Künste in Hamburg, as a young adult. She was thin, yellow blond, conventionally pretty, yet with a kind of sacred circle around her: unteachable. A suggestion from a teacher, Almir Mavignier, was enough to send her packing her bags for New York. In Manhattan, after two years of relative isolation, Darboven met Sol LeWitt in 1968, along with, among others, the artists Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner. Darboven’s father’s illness and eventual death brought her back to her childhood home; here she set up a sort of studio, along with a daily writing routine. This was how she made her way to the math, in which 1 + 1 = 1, 2, even as 3 = three three three: a methodology that privileged the act of counting. This was to be a key aspect of Darboven’s all-comprehending practice of time registration and would be expressed through the pages of checksum calculations the artist incorporated into her wall- and room-size installations of writing.

Installation view of Hanne Darboven’s “ERDKUNDE UND (SÜD-)

KOREANISCHER KALENDER,” 2019. Courtesy Sprüth Magers, Berlin. Photo: Timo Ohler.

Installation view of Hanne Darboven’s “ERDKUNDE UND (SÜD-)

KOREANISCHER KALENDER,” 2019. Courtesy Sprüth Magers, Berlin. Photo: Timo Ohler.

But I need to double back for a moment: in the summer of 1943, when Darboven was two, the Allies bombed Hamburg, at that time a centre of industrial production. The operation, code-named “Gomorrah,” began on July 24, 1943, a time of unusually arid weather, and lasted for eight days, creating at one point a 460-metre-high tornado of flames, with winds of up to 240 kilometres per hour and temperatures of 800 degrees Celsius. Asphalt burst into flame and fuel spilled into the river, causing the surface of the water to ignite. The attack is thought to have killed some 42,600 people, wounding another 37,000 and decimating the city. It was made possible by a radar-jamming technique known as “chaff” (code-named “Window”): clouds of tinfoil strips dropped into the air. The foil interrupted radar imaging, creating false echoes, a fuzzy array; it is an information technology, even in its obvious nature. The results were stupendous. The nearly 800 American and British bombers were effectively invisible.

Although the Allies did not target Rönneburg, where the Darbovens lived, they did haphazardly detonate excess armaments in the suburban landscape. In early July, just before the bombing, the Darbovens’ neighbours’ farm was one such site. Shortly after this event, the Darboven women fled to Lower Saxony, thus avoiding Operation Gomorrah by a matter of days, although their home was still standing when they returned two years later.

I mention these events less in an attempt to inspire pity for this wealthy family headed by a man who did profitable business with the Nazi Party than to point out a series of historical events for which Hanne Darboven was effectively present without the capacity for conscious memory or comprehension. Whatever else she lived before she began to make her “writing”—which was, by the way, the term she used for all her art—echolocations and bombings, the repeated hollowing out of vast architectural spaces, consumed her early youth.

In 1971, Darboven wrote to LeWitt from Germany:

Sol, am completely absorbed in <it>

<it> i wrote about although there

is nothing to write about —

<it> thinking and looking <it> and

<it> and doing <it>, writing <it>

and Oh Sol, i feel like 1968 when

i went to your place with my pages

of “68” again i would like to walk

to your place [a holy place] with

pages of : <it> no title no more,

words words words, oh, if you could

come here, to my place, oh — this

this time, good night my master love…

Hanne

On returning home, Darboven had in some sense taken up her ailing father’s place, becoming a manager of accounts. With her distinctive writing, she investigated the unintelligible side of information flows. She transformed information back into lines, into material. No more words, instead <it>. No more years, instead <it>. <it> was sometimes a loop, resembling a letter but not a letter; sometimes it was a number, treated not as a quantity but as a graphic image, something like a name (3 = three three three) but not a name, either. <it> was when a number was not itself and yet most itself at the same time, turned inward toward its own condition. “Numbers are the most neutral way of talking about things; no names, no objects, just the counting of numbers and the use of dates,” she said in an interview in 1994. Darboven placed herself in the midst of whatever <it> was.

Although Darboven’s checksums are synthetic, they also defamiliarize numbers, treating them as non-repeating, unique identities to be discovered

When I look at the drawings Darboven produced during her time in New York, I see her exploring the uses and pleasures of the grid in various ways, using graph-paper boxes as a series of slots to be filled in, organizing and reorganizing. On one page, a series of numbers appears, apparently sourced from a late-summer date, August 30, 1968. When she wrote to LeWitt concerning her “pages of ‘68’” did she mean this very series, Kleine Konstruktion (Small Construction) of 1968, with four sequences of repeating numerals, 30868, 86830, 68308, 83086, day/month/year, month/year/day, year/day/month, month/day/[inverted year]? What might it mean for her to be fondly recalling this earlier page of work in the year 1971, when she began producing more ambitious sums, as in 1933/8K = No. 1, a large-scale numerical permutation on 42 sheets of paper in which Darboven renders three as “3 3 3” and five as “5 5 5 5 5,” for example, elaborating a series that permits her to produce “K” sums through different combinations of added numerals? Although Darboven’s checksums are synthetic, they also defamiliarize numbers, treating them as non-repeating, unique identities to be discovered within one another, rather than as quantities or points in a cyclical calendric sequence. As historian Zdenek Felix points out, it is less that Darboven wants to manipulate the calendar in her calculations, than that the calendar functions as the ideal ready-made matrix, “a system within which unfolding and regression would follow their own laws.”

It is nearly a secondary result of her work with these numbers, the infinite supply in the calendar, that time is pressed together into the characteristic Darbovian event, a seemingly gratuitous value labelled “K.” “there / is nothing to write about,” Darboven joyfully informs LeWitt, who may have been her lover; she is ecstatic, having discovered how to “[do] <it>,” and possibly where to get “<it>,” how to immerse herself in a practice in which there is always more to write, more to manipulate, more loops and checksums, but no longer anything to discuss, “no more, / words, words, words.” As she would later say in an interview, “I wrote things down again by hand so that the mediated experience might impart something to me.”

Maybe [Gins], like Darboven, understands the space of the page as not just an opportunity for establishing semantic meaning, but also a site for immersing oneself in an experience of mediation

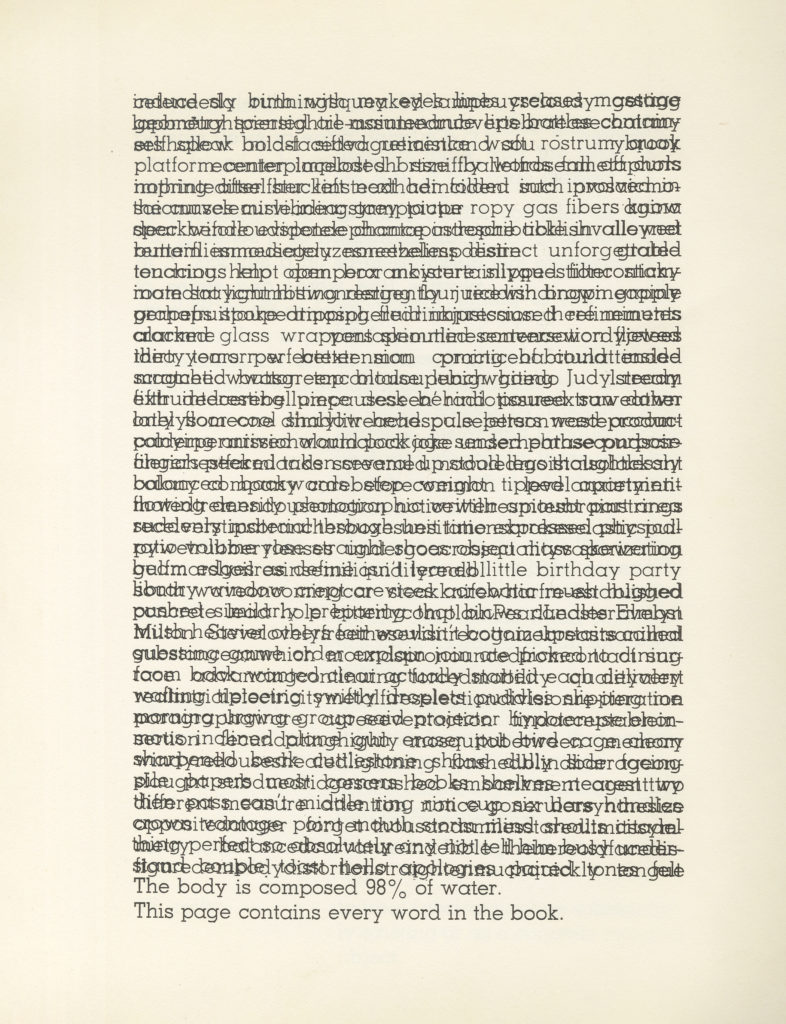

In the year of the holy walk(s) to Sol LeWitt’s place, another artist and writer, Madeline Gins, an American, lived and worked in Manhattan. Gins, like Darboven, was in her late twenties in the late 1960s, but unlike Darboven she was born in New York and raised on Long Island. She studied philosophy and physics at Barnard College, painting at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, and in the early 1960s she met, collaborated with and, in 1965, married Nagoya-born artist Shūsaku Arakawa, who, along with his mentor Marcel Duchamp, exhibited work in the Dwan Gallery’s 1967 show “Language to Be Looked at and/or Things to Be Read.” Perhaps it is the recent entry of language into visual art that moves Gins to do so much work on her typewriter. Perhaps she sees herself as typing up not just pages but images of a kind. Maybe she, like Darboven, understands the space of the page as not just an opportunity for establishing semantic meaning, but also a site for immersing oneself in an experience of mediation. When, in 1969, Gins publishes her experimental novel and artist’s book, WORD RAIN (or A Discursive Introduction to the Intimate Philosophical Investigations of G,R,E,T,A, G,A,R,B,O, It Says), it contains a story about mediation, perhaps of the kind Gins herself experienced during the course of the novel’s composition. The dust jacket offers the following summary:

In WORD RAIN, an unnamed narrator sits at a desk in a friend’s apartment reading a manuscript. Surrounding the undefined character is a birthday party taking place in the next room, a glass of pineapple-grapefruit juice that is supposed to be pure grapefruit juice, the loose leaves of the manuscript, and the variable weather conditions. The pages of the manuscript slide to the floor. The weather turns misty and cold. Dishes rattle in the kitchen nearby. A package is delivered. It feels like rain. As each of these distractions occur playing against themselves in almost musical variation, the reader either opposes or flows with them as she reads. Sitting at the desk, she sometimes skims pages day-dreaming or catches the rhythms and reads in word blocks while the text fills itself in…

The reader of WORD RAIN, at once a character in Gins’s novel and an individual independent of the prose, finds numerous textual strategies at play: citations and appropriations of material from other books, as well as a detailed accounting of the by turns elating and distressing phenomenology of reading. The narrator’s (fictional) reading has peculiar results—special effects, one might say. At times she seems to encounter a version of herself in the text, whom she attempts to instruct or salute as from a distance; these moments feel elegiac, suggesting that reading can be an act of reconciliation with, or loss of, the self. At other times, the effects felt by the protagonist-reader are directly physical, synesthetic, as in a passage in which, instead of functioning to deliver semantic sense, words ossify: “The word face was a stone. The word guess was a flint. The words a, the, in, by, up, it, were pebbles. The word laughter was marble.” At the conclusion of this passage, the protagonist-reader seems to become one with these textured, surfaced words: “The word read was mica and I was granite.” It’s a phrase in which the “I” mentioned is at once a term in the manuscript the protagonist reads and also a possible name for the reader, herself. In either case—in either reading—reading is alchemical and transporting.

“I” is at once a term in the manuscript the protagonist reads and also a possible name for the reader, herself. In either case—in either reading—reading is alchemical and transporting.

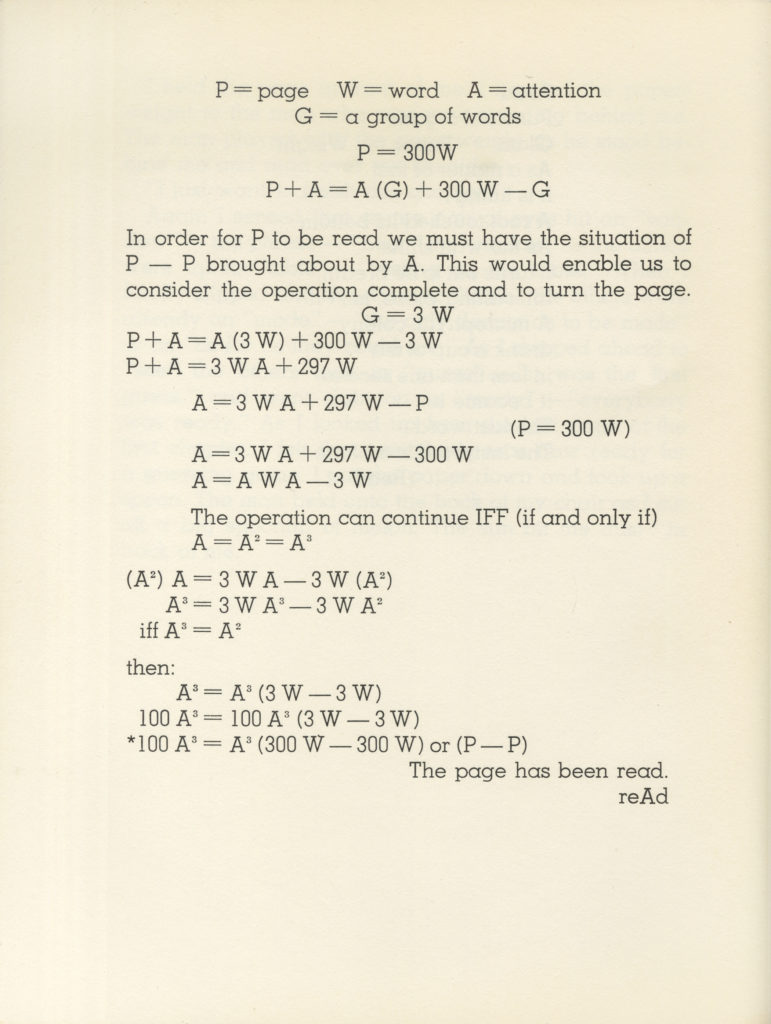

WORD RAIN also makes use of an eccentric form of mathematical notation (what Gins calls “oiled geometry, liniment algebra and creamed mathematics”) to quantify the text, an imaginary math. Gins’s math is designed to account for the number of words and letters used in a page; it allows for an alternate method of representing a page of writing, that is, by means other than semantic paraphrase, and therefore seems related to Gins’s understanding of writing and reading as having quantifiable, material qualities. Gins summarizes algebraically, such that sentences can be compressed into variables and arranged into formulae (“A = 13W + M1,” where “A = the first sentence,” “W = word” and “M = meaning”) explaining relationships between meaning and energy expended in the reading process across a paragraph or page. In this math, a given passage occurs again, for a second time—and differently. Semantically represented events are lost, but the events of the words themselves and the event of semantic meaning are rendered more prominent by means of mathematical generalization.

Madeline Gins, page from WORD RAIN (or A Discursive Introduction to the Intimate Philosophical Investigations of G,R,E,T,A, G,A,R,B,O, It Says), 1969. Originally published by Grossman Publishers, New York © 1969 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins.

Madeline Gins, page from WORD RAIN (or A Discursive Introduction to the Intimate Philosophical Investigations of G,R,E,T,A, G,A,R,B,O, It Says), 1969. Originally published by Grossman Publishers, New York © 1969 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins.

“am completely absorbed in <it>,” Darboven wrote in 1971. Gins, meanwhile, describes an experience of “tak[ing] up inside” of letters and words, where the self is a sort of membrane reading renders permeable. The choice not to differentiate between personhood and the activities of writing (Darboven) or reading (Gins) perhaps seems more familiar to us today, given our movement toward an increasingly scriptural society. Yet, moving beyond “words, words, words” into spaces and states of extreme mediation does not come without loss—and what exactly goes missing here is difficult to quantify. If I attempt, instead, to qualify this loss, I might suggest, necessarily engaging in speculation, that it has to do with the historical moment in which both Darboven and Gins were coming to consciousness and early maturity as artists, not to mention the shared year of their respective births. Language, although distinct from information in some contexts, is often treated as, or transformed into, data. By the middle of the 20th century, data had ceased, if ever it had been, to be a raw or mere tool—having become instead a weapon, an instrument of politics, a commodity. The theatres of the Second World War, with their various demands, could only hasten this process, and the civil societies that succeeded the conflict inherited new technologies, beliefs, fashions, drugs and foods from the business of making war. I sometimes think that one major thrust of Conceptualism, as a broad artistic movement, is to aid people in confronting the cybernetic transformation of everyday life in the postwar period, in which a word is no longer word but data; in which movements are data; in which persons, places and things have all become information. Darboven and Gins, paradoxically, deployed their math as a sort of antidote, transforming information back into things.

Madeline Gins, page from WORD RAIN (or A Discursive Introduction to the Intimate Philosophical Investigations of G,R,E,T,A, G,A,R,B,O, It Says), 1969. Originally published by Grossman Publishers, New York © 1969 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins.

Madeline Gins, page from WORD RAIN (or A Discursive Introduction to the Intimate Philosophical Investigations of G,R,E,T,A, G,A,R,B,O, It Says), 1969. Originally published by Grossman Publishers, New York © 1969 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins.