When four Confederate monuments came down in New Orleans this spring, some worried history was being irrevocably and physically erased from the landscape. Never mind, one supposes, the inescapable embeddedness of the Confederacy elsewhere in the names of schools, a major highway, even the neighbouring community of Jefferson Parish. The monument’s supporters—championed by President Donald Trump—heralded the statues as public art.

And now that a stories-high NOLA podium that once carried the figure of Confederate general Robert E. Lee is, instead, conspicuously empty—and amid the omnipresence of America’s extraordinary political moment and its volatile president—it happens to be a highly auspicious time to explore the implications of history and art, of race and colonialism, cultural synthesis, nationalism and the land upon which New Orleans was built 300 years ago.

The triennial international exhibition Prospect.4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp, which offers reflections on many of these themes, opened in New Orleans this past weekend, bringing the works of 73 artists (including some Canadians) to galleries, parks, museums, the banks of the Mississippi River and even a streetcar.

The exhibition was already designed to coincide with celebrations of the city’s 300th birthday this winter, but artistic director Trevor Schoonmaker agreed it’s become, “sadly, all the more timely.”

“Everything really feels like it’s just going to hell in a handbasket,” Schoonmaker, who is also chief curator of Duke University’s Nasher Museum of Art, told me. He’s never seen the American public so politically engaged, he said. He argued the scaffolding of white supremacy, among other systemic problems, is being revealed.

“At the same time, the artists are making these works that—you know, it’s such a sensitive, thoughtful response to the moment we’re in, and trying to find proactive ways or approaches to get out of it, to find a way out of the mess.”

The mess, or to use the exhibition’s vernacular, the swamp. Not to be conflated with Trump’s “drain the swamp,” a phrase deemed racist by many, which had hardly registered in Schoonmaker’s mind when he chose the exhibition’s title. Instead, in one of the many entwined ironies, Schoonmaker pulled the title in part from a quote from jazz musician Archie Shepp, who called jazz a “lily in spite of the swamp”—a metaphor evocative of the Louisiana’s humid, mucky landscape and one that explicitly describes both New Orleans’ vibrant cultural production and the enduring suffering of its Black citizens in particular.

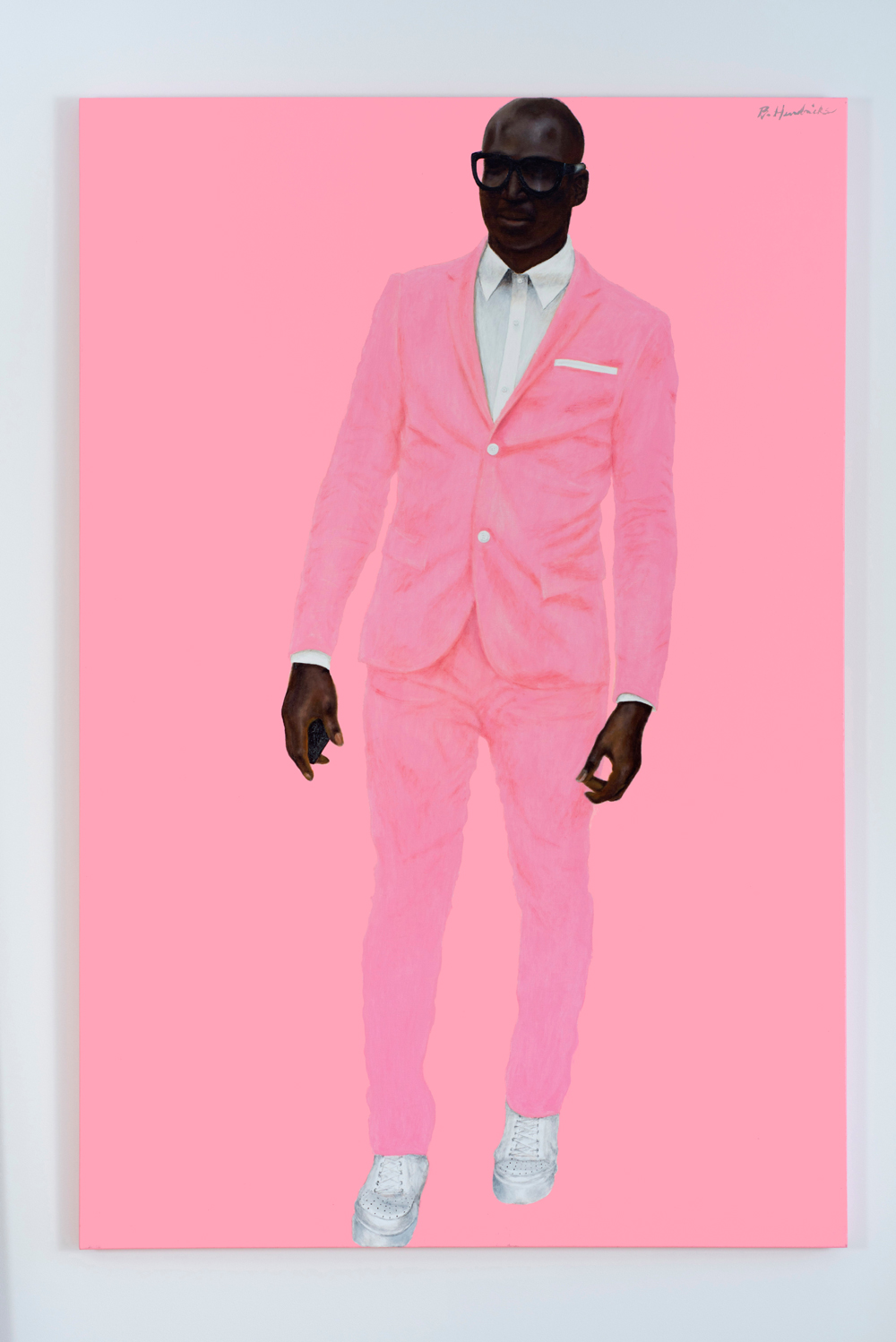

Barkley L. Hendricks, Photo Bloke, 2016. Oil and acrylic on linen, 72 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York © Barkley L. Hendricks.

Barkley L. Hendricks, Photo Bloke, 2016. Oil and acrylic on linen, 72 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York © Barkley L. Hendricks.

The show has created striking juxtapositions: Nearly a dozen large, iridescent, candy-coloured portraits of urban African-Americans by the late American artist Barkley L. Hendricks hang on the vaulted stone walls of the New Orleans Museum of Art’s cavernous lobby, just rooms away from the museum’s collection of pristine furniture from antebellum era plantations.

Also: Into the vacuum of what belongs in public spaces created by the Confederate monument controversy comes New Yorker Kara Walker’s upcoming installation Kataswof Karavan (planned for Prospect.4’s February program).This collaboration with jazz pianist Jason Moran will feature a custom-made steam pipe organ (called a calliope) housed inside a large covered wagon, blasting protest songs from Algiers Point, a public site on the Mississippi River once used to corral slaves.

Prospect.4: The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp probes echos of Deep South culture in cities around the world, seeking artists with overlapping concerns, including Iranian-Canadian Abbas Akhavan and Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore, both of whom present work with contextual ironies of their own.

For the exhibition, Akhavan created Service, an installation featuring an image printed on a casket-sized flag that remains folded and unviewable for most of the day, placed carefully on a kitchen table.

Once a day, for the final minute before the show closes, the flag is unfolded and hung next to the table. It remains there overnight, and is folded again before the show’s opening.

Crucially, “while it’s up for that one minute, no photographs are allowed of the image,” Akhavan emphasized in conversation.

For most viewers—myself included—the main experience will be of arriving at the wrong time. Of being denied access to the exact thing we’ve come to see. Or for those arriving at the right time, of a largely un-Instagrammable experience.

The reaction for some (as it was for me) might initially be irritation.

“That’s fair,” Akhavan told me. “But I think it’s more about restraint.”

Restraint, that is, around the image that is printed on the flag: a close-crop of a viral picture of Myeshia Johnson, the now-famous military widow, draping herself over her husband Sgt. La David Johnson’s flag-covered casket after he was killed in Niger.

“She wore this incredible dress that has this floral pattern on it, a magnolia or lotus-looking flower,” Akhavan said. (Looking at it, one might be reminded of plant motifs in his other works, like the large bronze casts of plants from around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Study for a Monument, shown of late at the Guggenheim.)

For Service, Akhavan cropped the source image so severely that not even Johnson’s face is visible—an effort not to further exploit her image.

“And so what’s printed on the flag is actually part of the American flag,” says Akhavan. “But where the stars would be is basically her shoulder, and that’s the lotus—the flowers have basically replaced the stars.”

Despite its title, its use of a funeral flag and its source image, Akhavan said the piece doesn’t question service or sacrifice per se (though viewers may not avoid such inferences).

“My interest was more about representation, and also ways of looking at images, and also ways of looking at people who are exploited through imagery or through political lenses,” he said. “It was a remarkable moment, and it’s so proliferated in really wrong ways, and it needs its own ritual of looking.”

Far from being conceived for the exhibition is Rebecca Belmore’s iconic megaphone, Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother, which appeared originally in 1991 in reaction to the Oka Crisis and celebrations of 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in North America.

The concept of speaking to the land feels especially precarious in southern Louisiana, as coastal erosion threatens the surrounding communities, aided by oil development and rising sea levels.

And yet, while chosen for its references to the environment, spirituality, protest and Indigenous cultures, Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan has been placed against the white walls of the New Orleans’ Contemporary Arts Centre among other exhibition works—removed from the site-specific natural landscapes for which it was made, away from the Mother to whom Belmore has, in the past, invited others to speak.

“Clearly, it’s meant to be outdoors and meant to be performed, and meant to speak to a very specific landscape and people,” Schoonmaker admitted. “But at the same time it transcends that, and it speaks to issues that we all need to be addressing,” in addition to being “stunning in its visual impact.”

Aside from the explicit politics of The Lotus in Spite of the Swamp, Schooner argued it’s political even in the choice of artists, many of whom are people of colour. Among them is Dawit L. Petros, a photographer based in Montreal, New York and Chicago; his project The Stranger’s Notebook, chronicling of a 13-month journey through Africa that ended in Europe, is another Prospect.4 highlight.

And while this show is not explicitly part of “the resistance”—a broad U.S. political movement that’s sprung up to resist Trump’s presidency—it’s hard to view Schooner’s exhibition as completely outside it.

Akhavan, for his part, argued America’s current politics has implications for everyone, especially racialized people around the world.

A certain “collegiality,” he says, could be one outcome of the current moment. White supremacists are “so prejudiced that they bring the rest of the world together. It could be Palestinians, Jews, Iranians, blacks, queers.”

From that collegiality, “there’s a lot of sophisticated, nuanced cross-pollinating,” Akhavan said, artistic and otherwise. “A rich conversation.” Something beautiful, something growing.

Rosemary Westwood is a writer and columnist based in New Orleans.