Near the centre of Cindy Phenix’s sprawling painting Polymorphism of Power (2017) are two faces, both self-portraits. One depicts Phenix nude, cross-legged and wild-eyed as she raises her engorged foot to her gaping mouth in a pose that seems to quote Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son. Just above, to the right, a bald-headed bust, modelled again on Phenix’s face, sits perched atop a twisted, fleshy plinth. Its features are placid and beatific, with a flushed pink colour and the air of a bouncy, phallic sex toy. Though she has placed herself at the heart of this ambitious canvas, Phenix nevertheless remains disguised, hidden among the whirlwind of fragments and incidents that churn across its surface. Even someone who knows Phenix would be unlikely to recognize her image without a prompt, in part because of how her expressive paint handling breaks up forms and blocks off surfaces, playing thick impasto against negative space, clear lines against textured volume. Her Saturn-figure’s face, for example, is a flat, white mask and its sex a bold red line, while its hair and limbs are all different flesh tones, like a doll pieced together from spare parts.

As its manifesto-like title suggests, this painting is preoccupied with primal questions of power and violence, desire and sexuality, especially as they bear upon female bodies and identities. With its crowd of leering, deconstructed women swarming around abstract architecture, in a psychological-fantasy bisected by a stream of fecal-brown sludge and dotted with bursts of green and yellow slime, Polymorphism of Power is Phenix’s most sensational statement to date (the work is roughly six feet tall and eight feet wide) of the feminist-expressionist ethos that animates her practice. It’s an approach that testifies to histories of violence while also seizing the female monster as an icon of power, reclaiming abjection as liberation from social norms—a gesture with a venerable tradition in feminist art. But her works are not always lurid—they often approach the social dynamics of public and private spheres with a more playful, contemplative tone, though her protean figures and unsettled scenes never fail to vibrate with manic energy.

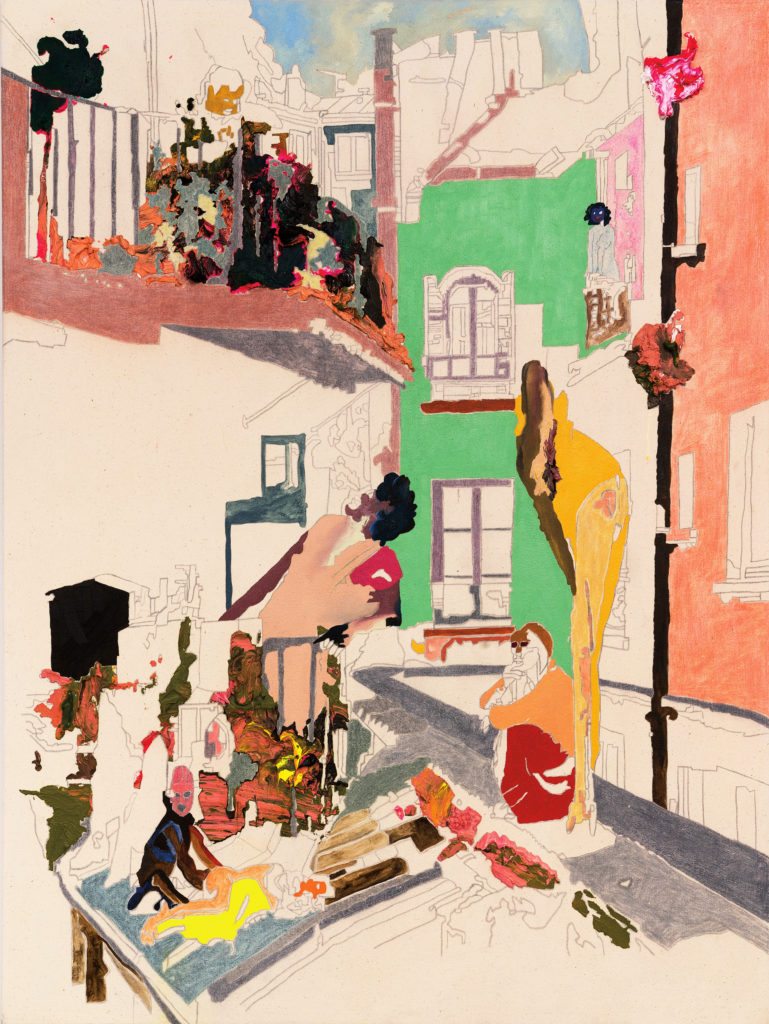

Cindy Phenix, Your Boring Game, 2016. Oil and pastel on canvas, 1.21 x 1. 82 m. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.

Cindy Phenix, Your Boring Game, 2016. Oil and pastel on canvas, 1.21 x 1. 82 m. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.

Her use of gestural abstraction and psycho-sexual themes also appropriates the legacy of “expressionism” in its many forms, from early-20th-century modernism to the mid-century existential heroics of the New York School and the splashy, cynical pastiche of 1980s Neo-Expressionism. While expressionist tropes are often associated with unbridled male egos and primitivist fantasies, Phenix follows a trail blazed by artists such as Maria Lassnig and Nicole Eisenman, deploying expressionism as a vivid mode of depicting female interiority and the affective experience of a sexist social world.

When Phenix painted Polymorphism of Power in 2017, she had only recently completed her BFA at Concordia University. That year she also embarked on residencies at the Banff Centre and at Montreal’s Les Territoires (mentored by artist Karen Tam), which marked the onset of an incredibly fruitful period. Following a solo exhibition at the Maison de la culture de Longueuil in the spring of 2018—in which every work sold—Phenix made her commercial gallery debut at Galerie Hugues Charbonneau, which caused a stir when every work found a buyer before opening night, leading Montreal’s La Presse to anoint her a “phenomenon.” And then, barely before the dust of the celebrations had settled, Phenix set off to begin her MFA at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Phenix’s reputation had been building well before 2018, however. She had already been shortlisted for the RBC Canadian Painting Competition in 2015, a year that Hugues Charbonneau was on the jury. While her talent has been recognized early and often, and pushed forward by crucial mentors and supporters, she doesn’t come from an artistic background. Her parents run a roofing business in the Montreal suburb of Varennes, where Phenix grew up, and while they are now very supportive, they did require some persuasion to accept her choice to pursue life as a professional artist. Indeed, before starting her BFA, Phenix herself expected to end up teaching art in high school or CEGEP; prior to university, she studied fashion, graphic design and photography, not “fine art.” It was thanks largely to the intervention and inspiration of specific teachers that she was propelled down her current path. One of the first was painter Paul Hardy, who taught a painting class at Concordia and encouraged Phenix to experiment with mixing different kinds of paint application on one canvas. Artist François Morelli, in a drawing class, encouraged her to read more feminist literature, after he saw her reading Simone de Beauvoir. Phenix’s mentors at Concordia were mostly men, and she laments that she was never able to study with textile sculptor Luanne Martineau, whose work she admires. At this early stage, her work was evolving from abstraction into more figurative scenarios via experiments with Photoshop and collage, but the seeds of major evolution in her style emerged from her desire for immersion in feminist theory and community.

Women circulate, congregating over tables as men loom from balconies and peer from behind curtains. The ambiguous space of the scene, a patchwork of raw-canvas negative space and goopy impasto, evokes spills, disorientation and a glamorous but sordid atmosphere full of veiled threats.

During her BFA, she began a periodic series of what she calls “participation/discussion” groups that have remained a central and unique source of inspiration for her practice. For these groups, Phenix invites women to interact with artworks and to take part in haptic and phenomenological exercises involving props and installations that she creates. Participants are invited to share anecdotes and reflections as part of discussions guided by Phenix. She describes these open-ended meetings as “safe spaces to meet new people and exchange ideas.” Initially drawn from her personal friends, the groups’ membership became increasingly public as Phenix sought a broader range of ages and life experiences. Though she emphasizes that these are not reading groups (gatherings do not involve discussing books or theoretical texts), Phenix notes that the idea of such meetings was inspired by her own reading of certain feminist thinkers.

First, she cites Iris Marion Young, whose Justice and the Politics of Difference (1990) argues against defining “woman” in essentialist terms and advises that collaboration on common projects allows women to relate without relying on biological attributes or pre-established and exclusive categories. (Phenix particularly points to Young’s interest in “undoing ‘woman’ before representing ‘woman,’” a notion that I think echoes Phenix’s own predilection for rendering figures as unstable accretions of collage-like fragments.) Phenix also points to Sara Ahmed, Angela McRobbie and bell hooks as central to her ideas about the need for feminist solidarity and the centrality of embodied, collective experience in the process of liberation. Her own groups, though not exactly activist in orientation, draw inspiration from the history of feminist consciousness-raising through informal discussion.

The poses, gestures and stories shared throughout the process of these discussions have served Phenix as fertile material for her compositions, which almost always feature groups of women. We Don’t Really Talk (2017), Acceptance of What Surrounds You (2018) and The Light Does Not Increase (2018), for example, all include knots of female figures in public or domestic settings, clustered around tables, talking.

Cindy Phenix, Balcony View on Negotiations, 2018. Oil and pastel on canvas, 1.21 m x 91.4 cm. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.

Cindy Phenix, Balcony View on Negotiations, 2018. Oil and pastel on canvas, 1.21 m x 91.4 cm. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.

The Light Does Not Increase—another of Phenix’s largest canvases—draws directly from an anecdote that a woman shared during one of these meetings. Phenix had been working on a series focused around the notion of the balcony and thinking about the invention of the boulevard in 19th-century Paris: flâneurs stepping out to be seen in the street while the bourgeoisie observed from their balconies, looking at others and being looked at. She had shared a list of questions for her discussion group, one of which was: What is the highest place you have ever been? For one participant, the question quickly became a metaphor: it made her think about the “highest” place she had been socially. She related a story about being invited to a professional dinner among affluent company only to be personally and publicly humiliated, after which she quit her job. The Light Does Not Increase depicts a riotous scene at a fashionable party. Off-centre on the left, the viewer’s eye plunges into the cleavage of a woman with a mask-like face who seems to have half-fainted over a staircase. Throughout, women circulate, congregating over tables as men loom from balconies and peer from behind curtains. The ambiguous space of the scene, a patchwork of raw-canvas negative space and goopy impasto, evokes spills, disorientation and a glamorous but sordid atmosphere full of veiled threats and pitfalls.

This work is also a fine example of the interplay between abstraction and figuration, impasto and negative space, in Phenix’s practice. Phenix describes how she usually begins her paintings with a thick, abstract, messy stroke: “I believe everything builds itself surrounding the first brush mark,” she explains. “Therefore, for me, it makes sense to start with abstraction and build up on it…the first action applied is to break the painting.” These kinds of marks, often fantastically thick, sculptural agglomerations of paint, offer Phenix rich associative possibilities, sitting somewhere between control and freedom. They’re acts of willed expression that are, at the same time, accidents and surprises. They define the space, suggesting architecture or natural forms; their mass implies falling apart, closing in or sliding away; they evoke clothing, dense textiles, impressive dresses, costumes for an event. These kinds of marks help delineate what Phenix calls “heavy situations,” the kinds of thematic narratives she’s drawn to.

Cindy Phenix, A Feeling of Movement, 2019. Wood, acrylic, polystyrene, plaster, Plasticine and rope, dimensions variable. Courtesy Northwestern University, Evanston, IL.

Cindy Phenix, A Feeling of Movement, 2019. Wood, acrylic, polystyrene, plaster, Plasticine and rope, dimensions variable. Courtesy Northwestern University, Evanston, IL.

Phenix explicitly ties the materiality of her paint strokes to the idea of abjection. “Their physicality looks like cakes that you want to eat or your shit on the floor,” she remarks. Phenix seems to relish how subjects like gluttony and fecal matter seem more disturbing when women are the protagonists of the narrative. In an email conversation, Phenix quotes Julia Kristeva’s classic definition of the abject in Powers of Horror (1980): “What disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite.” The idea of the composite, too, is central to her imagery. Phenix confirms that she deliberately seeks the effect of bodies and characters assembled from found objects, implying the tragedy of trying to attain an ideal constructed from readymade parts. Her women rebuke the pressure placed upon them to conform to such ideal types, but rather than suggesting quasi-surrealist visions of sad, broken dolls, Phenix is after a more assertive monstrosity. For her, fragmentation does not imply a failure of wholeness, but a gathering of forces, as well as the possibility of reconfiguration, the ability to transmute into something new. “They have all the experiences, all the knowledge,” she says. “They are the threatening force; they incarnate power.”

Phenix herself is undergoing a reconfiguration and a gathering of strength in the process of her graduate studies. The Art Theory and Practice program at Northwestern was her first choice for a variety of reasons: she wanted to work with artist Jeanne Dunning, but she also liked that students are assigned to a different teacher every quarter, which allows them to work with the whole faculty. “I had the impression that the size of the program would feel like a family,” she explained, “and it was crucial to me to work with professors who understood the significance of the feminist emphasis of my work.” To her, Chicago felt like a place where urgent political questions about race and gender were being hotly debated, and where grassroots and DIY activity gave the city a sense of open-ended potentiality. Northwestern also has a vigorous program of visiting scholars and artists: curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev was a visiting professor during Phenix’s first year, and studio visits over the year since have included Anna Boghiguian, Fia Backström, Jennifer Reeder, Amanda Ross-Ho and Amy Sillman.

Phenix has been experimenting with various new directions in preparation for her next body of work and eventual MFA graduate exhibition in 2020. She’s been making drawings using cut-outs on paper, cutting wood to make room-sized installations that feel like drawings and building wooden armatures to hang drawings on—new ways of literalizing fragments and exploring supplements and aggregates. While the props and environments from her participation and discussion groups constitute a separate body of work that she says is not really for exhibition, Phenix is moving more confidently into three dimensions and expanding on her earlier experiments with sculpture. She’s also thinking about fresco as a historical conflation of private and public space. She’s drawing on the walls. What’s clear is that the last thing Phenix is interested in is doing the same things over again. She says it might be because of her upbringing that she believes art can change things, and for that reason, she’s not afraid to change her own work. “If my work needs to change, it will change,” she says. “I have so many more things I want to do.”

Cindy Phenix, Polymorphism of Power, 2017. Oil and pastel on canvas, 1.82 x 2.43 m. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.

Cindy Phenix, Polymorphism of Power, 2017. Oil and pastel on canvas, 1.82 x 2.43 m. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.