Some crises in the Canadian arts sphere are recent—like COVID-19—while others have a longer track record, such as harassment, bullying and discrimination in arts workplaces.

More than two years ago, in January 2018, Canada’s big national arts funders—the Canada Council and Canadian Heritage—vowed “no tolerance” or “no place” for harassment in the organizations they fund, a commitment recently reaffirmed in a mandate letter to the new minister of Canadian heritage.

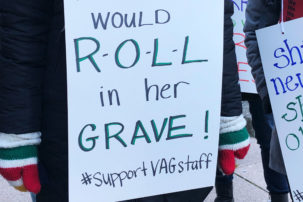

But Canada has a long way to go in making harassment-free arts workplaces a reality. Publicly, the Remai Modern continues to be involved in a human rights commission complaint; both the Toronto International Film Festival and Vancouver International Film Festival recently issued statements following concerns about one of their former programmers; and a new external review at OCAD University found its policies on harassment were “out of date.” Canadian Art has also received personal inquiries from arts workers asking that multiple cultural organizations be investigated for harassment and unsafe workplaces.

It seems that multiple arts organizations in Canada still struggle with issues of accountability, resolution and safe workplaces.

“At the time when several incidents had occurred in [my] workplace, there were no policies in place to address how and to whom to report workplace safety, bullying and harassment issues, and no human resources department,” one arts worker told Canadian Art on the condition of anonymity.

“Employees could detail an issue to a trusted colleague for guidance on resolution or report an incident to a board of director,” this worker says. Yet, when they did follow official procedure, “no accountability or resolution was professionally or officially addressed with employees.”

In this way, arts institutions, along with national arts funders, have continued on—and even grown—while harassment has persisted. At the same time, the careers of more than a few people in the arts sector have not persisted: “The toxic environment,” says the arts worker we spoke with, “forced me to leave my position.”

There are some anti-harassment tools for the arts being explored nationally, often with Canada Council and Canadian Heritage support. But whether those initiatives are coming fast enough, and with enough scale and scope, for workers and contractors involved with some of Canada’s 1,750-plus arts organizations is another question.

So is the issue of whether individual organizations can really be trusted to self-report to funders when they are having a workplace harassment issue—and whether boards of directors in Canada’s arts scene are up to the growing task of making the workplaces they’re legally responsible for healthier and more accountable.

“There is a need in the sector for help, both for employers and for employees and contract workers,” says one arts expert regarding harassment in the sector. But that help can be hard to come by.

In September 2019, the Cultural Human Resources Council (CHRC), through funding from Canada Council and Canadian Heritage, started running in-person training sessions on harassment awareness for arts groups across Canada at no cost—and demand was strong.

“We’re receiving calls almost daily from organizations that want us to come in and offer that baseline training,” Grégoire Gagnon, executive director of the CHRC, told Canadian Art in February 2020.

Unfortunately the federal funding for those programs was due to run out soon, on March 31. Gagnon has applied for more workshop funding, and is optimistic about receiving it, but hasn’t received confirmation on this yet. (Canadian Heritage is allowing workshop funds to roll over until June 30 to account for some 10 to 25 sessions that were cancelled this month due to COVID-19; beyond that timeframe, Gagnon and his team continue to wait on new funding confirmation for subsequent months.)

Another thing the CHRC is doing right now—also through national arts funder support—is wrapping up a report on the feasibility of a national telephone hotline regarding harassment and unsafe workplaces in the culture sector.

A hotline is another anti-harassment tool that Gagnon says needs more funding—but such support hasn’t been secured yet.

“There is a need in the sector for help, both for employers and for employees and contract workers,” says Gagnon about the idea of a hotline. “There is a need for a resource people can turn to” when there are questions or issues of workplace harassment, sexual harassment or unsafe conditions.

Though the CHRC has tried to spread the word widely about arts-organizations responsibilities in creating safe workplaces—by providing those free workshops and putting other resources online, like training videos and quick reference guides, all under the banner Respectful Workplaces in the Arts—there are still many challenges to improving the situation.

“Not all boards are aware of their responsibilities in these situations,” says Gagnon. Also, “it can be hard to get boards together [for training sessions], especially for small organizations.” This is especially true for small- or medium-sized arts organizations with volunteer boards made up of people who work nine to five. “Getting them to take an afternoon off [from paid work] and come for training is difficult.”

Internally, Canadian Heritage and the Canada Council have, since 2018, been clarifying and refining their own tools for achieving their zero-tolerance goals on harassment within funded organizations.

This past winter, Canadian Heritage introduced a new protocol—formally called “an incident management framework,” says spokesperson Daniel Savoie, that “guides staff on how to deal with workplace integrity issues” in funded organizations. The Canada Council has its own related set of protocols already.

Both Canadian Heritage (known also by its ministerial portfolio designation, PCH) and the Canada Council use existing conditions in contractual funding agreements as accountability tools. In these agreements, those receiving PCH or Council funding must commit to fostering workplaces free of discrimination, harassment or sexual misconduct.

Funding agreements require recipient organizations to commit to providing respectful workplaces. Yet it’s often up to the organizations alone to self-report any problems.

When these contract provisions—or other ones around governance and finances—are at risk, PCH staff have the option to begin an “escalation process, which includes: briefing PCH management, notifying the recipient, applying corrective measures where relevant, and terminating funding, where applicable,” says Savoie. Similarly, at the Canada Council, “Failure to respect this commitment could result in the Council initiating a process to review and potentially reverse a grant decision where there are serious and substantiated concerns about the recipient or the funded activities,” says Ashley Tardif-Bennett, a communications advisor at the Council.

Yet there are still challenges in following through on those zero-tolerance tools. For one, it’s largely up to individual organizations to self-report to Canadian Heritage or the Canada Council when workplace issues emerge.

“Recipients must immediately inform the department of any fact or event that might compromise the terms and conditions of their agreement, such as workplace issues, lawsuits or audits,” Savoie says. If concerned arts workers feel that the process is not functioning in terms of making departmental funders aware of an organization’s workplace risks, those workers “can also communicate with PCH, or may decide to make a situation public,” Savoie notes. But the primary means of reporting workplace risks is still meant to be through an arts organization’s leadership to PCH program officers.

Likewise, the Canada Council expects organizations to self-report issues, and advises that concerned workers go through official workplace or legal channels to get action. “The Canada Council does not play a direct role in investigating complaints of harassment. Complaints must be addressed to the organization in question,” explains Tardif-Bennett. She adds: “We encourage workers who have experienced harassment to utilize the established reporting mechanisms within their organizations and access support through their professional association or union and seek legal advice from a lawyer.”

Timelines for funding consequences, once a workplace-issue breach becomes apparent, can vary quite a bit. Though funding agencies often begin their assessments immediately, deadlines for finishing up are largely open-ended. At the Canada Council, this is to “include factors like the organization’s capacity to undertake proper actions, such as an independent investigation,” says Tardif-Bennett. At Canadian Heritage, says Lavoie, “the escalation process is determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the specific circumstances of each alleged incident and the organization involved.”

Board and leadership patterns in the arts could complicate reporting of harassment and other workplaces issues to national funders.

Reaching out to boards of directors is also key if workers are concerned about harassment or workplace safety in their organizations and want arts funders to be aware of that. Here, further obstacles may emerge.

“The best way to bring these issues to Council’s attention is for individuals to address their complaints to the Board of their organizations directly, who have a legal duty to abide by applicable employment legislation,” says Tardif-Bennett. “Ideally, these organizations would proactively contact Council to inform us of a situation and establish what measures they are taking to remedy the situation.”

But there’s the fact that boards in Canada—whether for-profit or non-profit, corporate or cultural—are often poorly equipped to monitor workplace culture concerns and harassment in their organizations.

“Director duties have really expanded” in the last decade, observes Rahul Bhardwaj, president and chief executive officer of the Institute of Corporate Directors (ICD) in Toronto. Safe workplace issues for boards have “probably never been as potent an issue as they are right now,” he notes. “There has been a significant shift in expectations from a public and stakeholder standpoint which will raise the bar for what directors need to think about as well.”

Tools boards can use to monitor workplace culture include exit interviews, regular employee surveys and site visits, as well as “tying senior manager compensation to scores around culture on a staff compensation survey,” says Bhardwaj. Training resources, such as ICD’s courses Board Oversight of Culture, and Negotiating Uncertainty in the Era of #MeToo, are also useful.

“There is a very small community very reliant on personal references and networking—and that is a silencing dynamic right there,” says one expert.

Patricia Bradshaw, a professor in the Sobey School of Business at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, says the makeup of arts boards in particular can make it hard to report and deal with workplace integrity issues, harassment included.

“In arts organizations, often people are put on the board because they are able to do fundraising—especially for big organizations. You want those prestige names on the board, people who will give money themselves or who have connections to other people who can give money,” Bradshaw observes. “You want people with a philanthropic background. But many of them are on a lot of boards and don’t have the time to do the kind of oversight and use some of the [workplace oversight and governance] tools, which I think is an added wrinkle in the arts sector.”

Leadership patterns in the arts also complicate the issue: “I think in particular in the arts, leaders are these charismatic figures,” Bradshaw says. “They have that aura around them often, and it’s hard [for board members] to challenge somebody who’s got that artistic vision.”

Bradshaw thinks boards, whether for-profit or non-profit, need to consider harassment and unsafe workplace culture as part of its regular risk evaluations.

“Annually…this should be in the risk matrix boards need to fill out. What is our risk on cybersecurity? What is the risk of maintenance on our building? What’s our reputational risk if there is a toxic culture?” Those “checks and balances” are needed every 12 months, Bradshaw says.

And these tools are more needed than ever in the arts, because of the way the community is structured.

“There may be some unique dynamics” around harassment in the arts because the scene is so small, says Bradshaw. “There is a very small community very reliant on personal references and networking—and that is a silencing dynamic right there.”

On the ground, it’s clear many arts workers would welcome new mechanisms to break the silence around harassment in the arts—and would like to see the funding accountabilities that national arts funders promised back in January 2018 become a more widespread reality.

“For any organization’s culture to change, you need everyone to feel empowered,” Grégoire Gagnon of the CHRC says. “Everybody should be able to speak up and no one should have to deal with a toxic workplace.”

Even though many arts workplaces are at the moment more physically dispersed or on pause due to COVID-19 concerns, that doesn’t mean they are necessarily equitable or safe—or immune to cyberharassment and the like.

“There are lots of people in the community who have wanted to say something, but everyone wants to protect their reputation,” says the arts worker who told Canadian Art they left their job because of a problematic workplace. “These issues are still happening in publicly funded institutions,” they say. “And we need to have people talk more about it.”

Update: On March 29, Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault confirmed on Twitter that the Cultural Human Resources Council would be receiving new funding for its anti-harassment workshops, which will continue once it is safe to resume the workshops.