Why do Canadians have difficulty envisioning themselves and their work hemispherically? At a recent gathering in Mexico City, I was able to examine collaborations and exchanges among artists and scholars based in Canada and those from across the Americas. Every two years in a different city, the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics (Hemi), a 21-year-old institution founded by performance studies scholar Diana Taylor, brings together artists, activists and scholars at Encuentro, a popular gathering that is part performance festival and part academic research workgroups. Headquartered at New York University, Hemi is an important centre for political performance art, theatre and cabaret in the Americas. Today, it has dozens of collaborating human rights and social justice organizations and 60 member institutions, including OCAD University, the University of Manitoba and the University of Toronto, among others. This year, Hemi hosted its 11th Encuentro in Mexico City, with most of the panels, workgroups, exhibitions, keynotes and performances presented at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and in the historic city centre. It included performances by local and international artists, theatre pieces and cabarets, as well as keynotes by Judith Butler, Richard Schechner and Jesusa Rodríguez.

Lukas Avendaño & Edgar Cartas Orozco, Where is Bruno?. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Manuel Molina Martagon.

Lukas Avendaño & Edgar Cartas Orozco, Where is Bruno?. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Manuel Molina Martagon.

Lukas Avendaño & Edgar Cartas Orozco, Where is Bruno?. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Manuel Molina Martagon.

Lukas Avendaño’s Where is Bruno? was the first performance, and was one of the highlights of the gathering in Taylor’s opinion. In it, Avendaño borrowed the visual language of the famed Frida Kahlo painting The Two Fridas, and sat beside an empty chair while holding an image of his disappeared brother, Bruno. Members of the audience took turns sitting beside Avendaño and held his hand while musician Edgar Cartas Orozco played the trumpet. Performers in haz-mat suits infiltrated the audience and waded in a nearby pool, as if searching for Bruno’s remains, much like how others in Mexico and elsewhere must search for the bodies of disappeared friends and family members. It was a beautiful and poignant performance. York University theatre professor Laura Levin also cited Violeta Luna’s work REQUIEM #3: Body Graves as a highlight, because it “involved a powerful audience participation component in which spectators were asked to sift through soil with a spoon, one at a time, over a long stretch of time. This action implicated us in processes of mourning and the forensic search for justice for the murdered and disappeared.”

Ongoing violence throughout the Americas came up in many of the performances, workgroups and talks by artists and academics. The feeling of the gathering was one of hope but also desperation, as participants asked themselves how artists, activists and scholars could address the climate crisis, the increase of white supremacy and xenophobia, the rise of right-wing governments and ongoing violence toward women, and toward Indigenous and queer communities. It was overwhelming, but many performances created situations that connected us through humour, kinship and generosity.

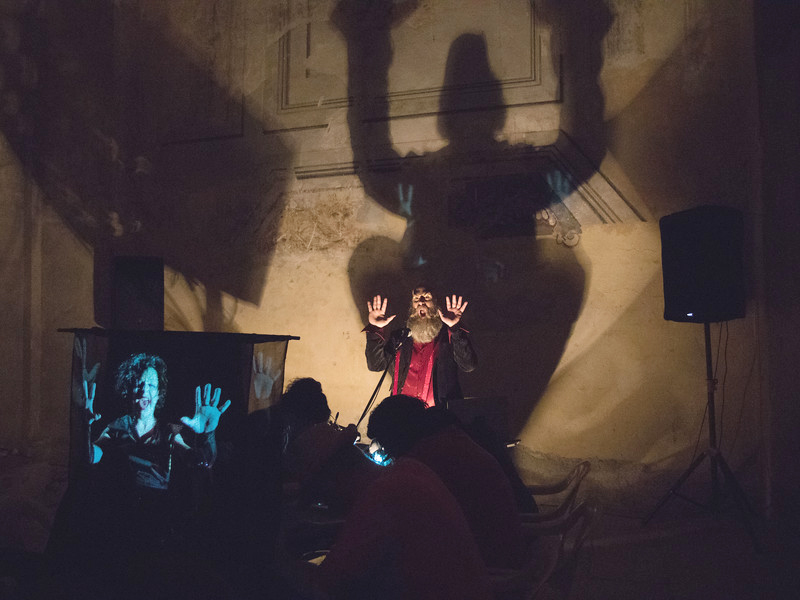

Las Reinas Chulas S.A. de C.V., The Wretched. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City, Mexico. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Julio Pantoja.

Las Reinas Chulas S.A. de C.V., The Wretched. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City, Mexico. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Lorie Novak.

Las Reinas Chulas S.A. de C.V., The Wretched. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City, Mexico. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Julio Pantoja.

Las Reinas Chulas S.A. de C.V., The Wretched. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City, Mexico. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Alexei Taylor.

One of my highlights was The Wretched, by Mexican cabaret group Las Reinas Chulas, a humorous piece about feminist resistance in a past-present-future time warp. Set during the French Revolution, the cabaret showed five women stealing the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and adding their own feminist declarations. Looking outside their window in Paris, they see the decapitated heads of Donald Trump and Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro paraded in the street instead of those of the French aristocracy. Trump, who is not well liked in Mexico, was a recurring topic, and even appeared as a character who hosted one night of performances. Dot Tuer, a cultural historian based in Toronto, also mentions One Melon…!! Your Melon…!!, by collective El Ciervo Encantando, as an important performance for its use of humour and song to discuss American-Cuban relations, American tourism in Cuba and exoticizing stereotypes.

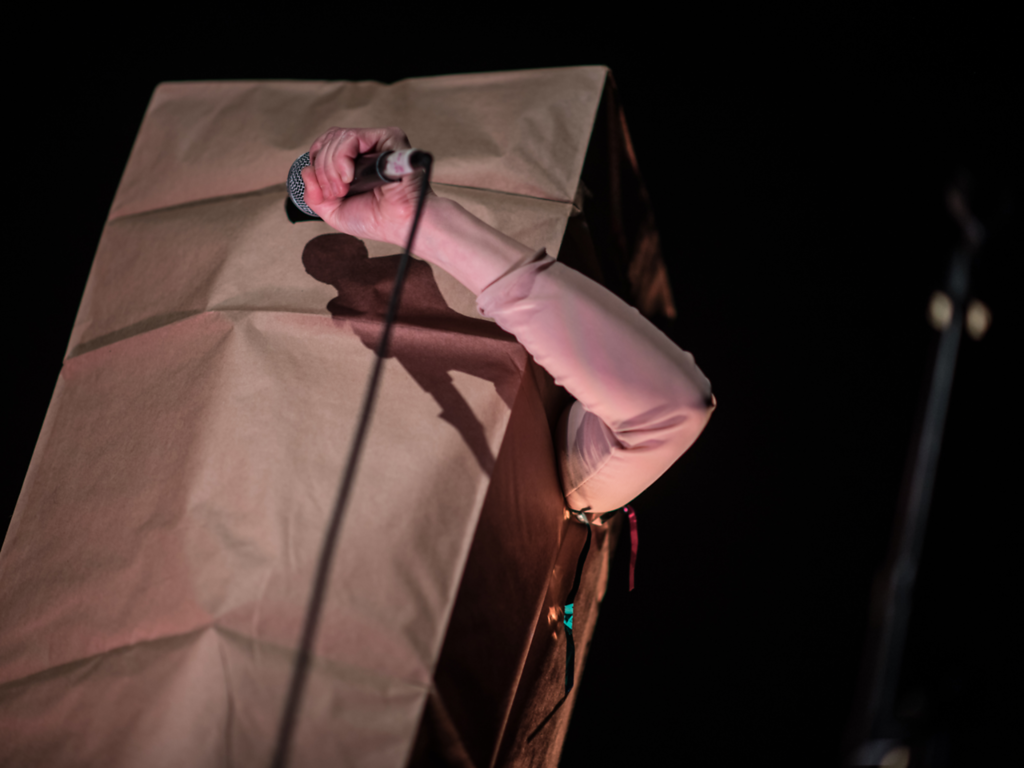

2boys.tv, CatoptROMANTICS, Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Julio Pantoja.

2boys.tv, CatoptROMANTICS, Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Julio Pantoja.

CatoptROMANTICS by 2boys.tv, the Montreal-based duo Stephen Lawson and Aaron Pollard, was another significant piece, according to Taylor. The artists set up a seance-like environment for a participatory, bilingual performance that explored who is missing at the table. Language, translation and understanding were important themes and practices at Encuentro, with events in Portuguese, Spanish and English. University of Toronto professor T.L Cowan, who facilitated a workgroup on Cabaret Methods, commented that “it really makes a difference for people to be able to work in the language in which they are able to communicate to their satisfaction, rather than defaulting to dominant languages, or the language that the most people understand, which is, because of linguistic imperialism, English.”

Performances were held in theatres, plazas, streets, buses, art galleries and bars. Encuentro’s late-night performances, Trasnocheos, were also a highlight for many, including memorable pieces by Ecuadorian duo Pacha Queer and Canadian Jess Dobkin. Dobkin also collaborated with Levin on Talixmxn: participants were given a cotton bag for collecting small objects from a number of performers for the duration of the gathering, thus enabling a personal, material archive of Encuentro and the opportunity for participants to engage with artists beyond their performances. It was these in-between times, while waiting in line or riding the bus, Dobkin explained, that the most interesting exchanges happened.

Jess Dobkin, You had to be here. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy the Artist. Photo Dahlia Katz.

Jess Dobkin, You had to be here. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy the Artist. Photo Dahlia Katz.

The participation of Canadians in Encuentro has increased in the past years because of scholars like Taylor, Tuer, Levin and Peter Kulchyski, and following the establishment of the Canadian Consortium on Performance and Politics in the Americas. Encuentro is one of the few instances where artists based in Canada meaningfully engage with artists from other parts of this hemisphere. The Canadian popular imaginary generally does not envision Canada as part of the Americas, so I was interested to observe how art and scholarship made by people in Canada was presented and perceived within a strictly hemispheric context. Many of the artists and scholars I interviewed agreed with my observations about the Canadian imaginary. Some mentioned that Canadian identity is one defined in contrast to the United States, thus preventing Canada from seeing itself as part of this larger community, while others cited Canadian exceptionalism and colonialism. Cowan says that “artists and scholars from Canada might not see themselves in relation to Latin America because of US- and Euro-centrism.”

“If you scratch beneath the surface, you discover a profound imperial/colonial gaze in Canada that brackets Latin Americans as ‘somewhere down there,’” Tuer proposes. “The interest in Latin American art and art history outside of Latinx communities is almost nonexistent in Canada.”

Levin says that “Canadian exceptionalism—which presents Canadians as tolerant, enlightened peacekeepers, as concerned environmentalists, and as welcoming to immigrants and refugees—makes it difficult to see the ways in which Canada is implicated in human rights abuses throughout the hemisphere.” Taylor recalls asking, “What is the role of Canada in the rest of the Americas?” during a conference in Toronto some years ago. She says her question was met with blank stares, adding: “Canada has a huge financial interest in the Americas that involves mining,” but Canada’s heavy economic investments in the Americas have not included Canada seeing “itself as a cultural actor.” Levin, who was a co-convener in a workgroup about mining and extractivism, says, “Canadian mining companies, for example, are responsible for violence, conflict, and environmental destruction in Latin America, but these realities aren’t discussed because they don’t square with the image of nation that Canada routinely performs on the world stage.” For Tuer, one of the strengths of Encuentro is to dislodge Canadians’ fixed positionality so that they can start to think hemispherically.

Tsēmā Igharas & Jeneen Frei Njootli, Sinuosity. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Julio Pantoja.

Tsēmā Igharas & Jeneen Frei Njootli, Sinuosity. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Julio Pantoja.

The artists I interviewed also acknowledged the lack of hemispherical thinking within Canada, but also referred to connections they’ve been able to make with artists from the rest of the Americas in ways that go beyond this barrier. Tsēmā Igharas and Jeneen Frei Njootli performed a beautiful and touching work about nurture, intimacy, kinship and a playful resistance to resource extraction. Igharas says she was able to foster international connections “by being Indigenous and through comparing colonial experiences.” She learned about the different ways colonization was carried out throughout the continent, which she describes as “both a barrier, and a way to connect.” Toronto-based artist Coco Guzman mentions how queerness can also be a connection. “If the hemispherical is about creating connections that surpass the political borders of the continent,” says Guzman, “I think it is through queerness that I felt it the most, as queerness proposes new perceptions of time and space, and of movement, of fluidity, of change, of inhabiting.”

Some performances, in keeping with Encuentro’s 2019 theme of humour, noise, satire and laughter, approached serious issues in more unconventional ways. Montreal-based artist Alex O’Hara presented a funny, honest and critical 50-minute performance in English, Spanish and French. Described as a deconstruction of white privilege, O’Hara’s performance was a critical understanding of race relations in Canada within the context of late capitalism. The highlights were her introductory monologue, and the installation of overlapping, trance-like videos in which she played a “nice white lady” from Canada. In an exaggerated voice she says, “I don’t see race. I’m not racist, I’m Canadian…Look at Justin Trudeau, he’s so sorry…Where are you really from?…Why don’t you take the apology and move on…Why are you so angry?…Can’t we just be nice?…You just need a nice Chai tea.”

Alexis O’Hara, OUFF. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics.

Alexis O’Hara, OUFF. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics.

For Taylor, the greatest takeaway from organizing and participating in Encuentro is realizing that it creates a community of people who ask, “What can we as activists, artists and scholars do to work together to try to bring about some sense of social justice and responsibility, but always through humour, through art, and through interventions that ask us to reflect deeply and invite us to go beyond our borders and our local issues to realize that we’re all actually involved in very similar struggles?” For me, Encuentro became an act of solidarity, a way for people to not feel alone in their struggles and to come together to build kinships, and perhaps have a laugh. It made me realize that we can be creative in how we build connections to each other despite our differences, and that our tools for resistance are expansive.

The DoMystics, (In)terfertilization: Of Word and Flesh. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Manuel Molina Martagon.

The DoMystics, (In)terfertilization: Of Word and Flesh. Encuentro 2019, Mexico City. Courtesy Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Photo Manuel Molina Martagon.