How can Canadian museums engage a new generation of donors? What is an appropriate artwork or art cause to crowdfund for in a Canadian context? Why are some gallery members concerned when they perceive Instagram popularity as a significant factor for art gallery acquisitions and fundraising? And when should Canadian museums and galleries own up to a lack of professional crowdfunding expertise?

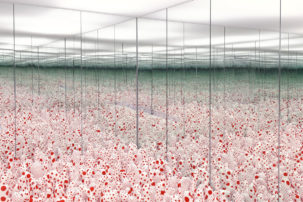

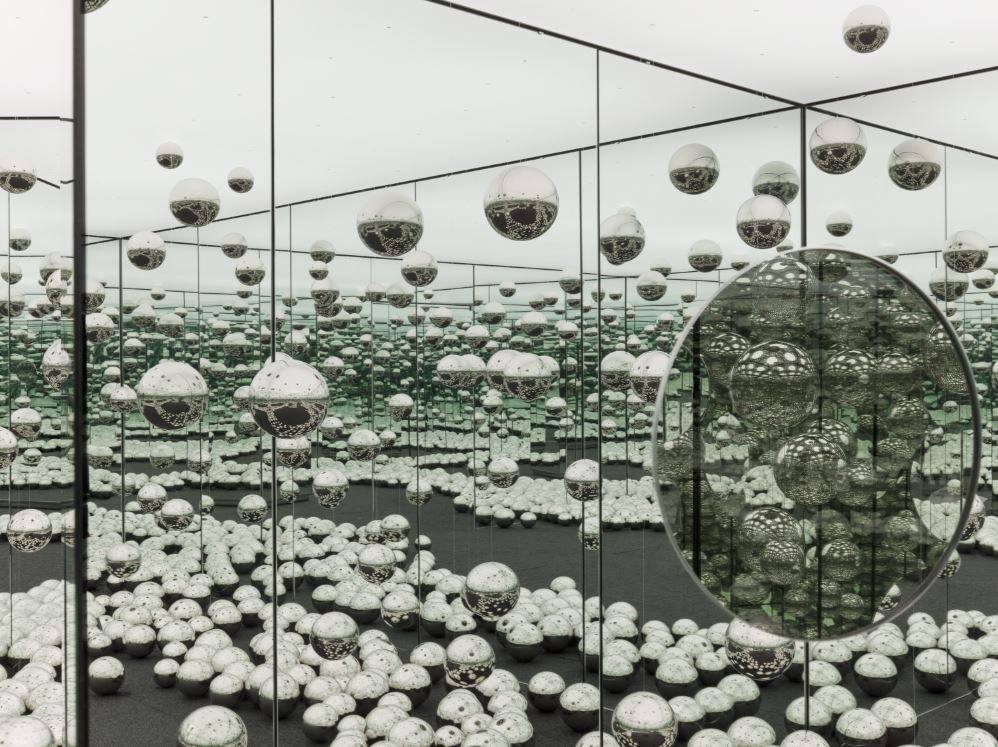

Yayoi Kusama, INFINITY MIRRORED ROOM - LET'S SURVIVE FOREVER, 2017. Wood, metal, glass mirrors, LED lighting system, monofilament, stainless steel balls, and carpet. 123 x 246 x 245 1/4 inches / 312.4 x 624.8 x 622.9 cm. © Yayoi Kusama. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / Singapore / Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London / Venice

Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

Yayoi Kusama, INFINITY MIRRORED ROOM - LET'S SURVIVE FOREVER, 2017. Wood, metal, glass mirrors, LED lighting system, monofilament, stainless steel balls, and carpet. 123 x 246 x 245 1/4 inches / 312.4 x 624.8 x 622.9 cm. © Yayoi Kusama. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / Singapore / Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London / Venice

Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio.

These are some of the questions that come up in reflecting upon the Art Gallery of Ontario’s recent attempt to crowdfund $1.3 million in 30 days in order to acquire a Yayoi Kusama Infinity Room.

The campaign launched on November 1. At that time, the AGO stated it already had $1 million secured toward a total $2.3 million Kusama purchase, installation and marketing cost, and needed the public to contribute the remaining $1.3 million to “help bring a Kusama Infinity Mirror Room to Toronto…forever.”

By November 30 of the campaign, which had been slated as the final day, less than half of the hoped-for funds had been raised. At the last minute, the AGO extended its crowdfunding campaign by three more days to December 3, eventually hitting $651,183, or just over half the original crowdfunding goal.

On December 4, the AGO announced that the rest of the needed funds for the Kusama, or $648,817, would be pulled from the gallery’s David Yuile & Mary Elizabeth Hodgson Fund. It was also revealed on December 4 that that the Yuile & Hodgson fund had been the source of the $1 million previously secured for the Kusama. Given that that fund was set up in 2005 through a $4-million bequest from the Estate of David Y. Hodgson, specifically for acquisitions of contemporary art, this use of the fund seems to make sense qualitatively. After all, it had already been used in past years to acquire works by Canadian artists like Brian Jungen, Suzy Lake and Kent Monkman, as well as by international artists like Pierre Huyghe, Steve McQueen and Adrián Villar Rojas—so why not a Yayoi Kusama, too? But quantitatively, it will be significant to some that $1.6 million of what was originally a $4 million fund has now gone toward a single Kusama artwork.

(Note: The AGO was asked prior to publication of this article if the Hodgson Fund had grown since its inception, and the gallery stated it couldn’t share such details. The day after this article was published, an email from an AGO spokesperson clarified that “the Hodgson Fund is an endowment fund that has grown significantly since it was established in 2005. As a result, we did not need to touch the fund’s capital for the purpose of acquiring the Infinity Mirror Room.”)

All this said, it must be noted that, in more than a few ways, the AGO’s Kusama campaign was also a success—“#InfinityAGO raised $651,183—the largest amount ever raised through online crowdfunding by a Canadian public art museum,” an AGO spokesperson points out via email. The project also had, the spokesperson states, “over 4,700 donors in just over 30 days, many of which were in the $25 to $100 range.” This is a strong indication that there are thousands of art-interested individuals in Canada willing to go the small-donations route toward an acquisition—and possibly other projects. And it has also resulted in the AGO being the first Canadian museum to acquire a Kusama Infinity Room—a move that puts it on the same level as just 18 other museums worldwide.

And yet, with 20/20 hindsight, there should much to be learned from this episode, both for the AGO specifically and for the Canadian museum sector in general, which to date has not engaged in much large-scale crowdfunding. Here are some of the possible takeaways.

1. Do consider crowdfunding as a necessary way to connect with millennials and other new donors.

“If galleries want to stay relevant to digital natives, they have to understand they won’t be getting cheques at galas the way the used to,” says Daryl Hatton, CEO of the Vancouver-based crowdfunding platform FundRazr. Crowdfunding, he says, “can be a way to expand your audience and donor base rather than leaning on people who have supported you for years”—and who are, frankly, aging out as options.

A huge transfer of wealth is about to happen in Canada in the coming decade, and arts organizations need to start developing younger donors if they haven’t already. “The problem is when [museums] are working on optimizing revenues, they are focusing on getting more out of their existing donors,” says Hatton. “That works for short term, but they need to talk” to new, younger donors, too, to be sustainable in the long term.

2. Don’t start crowdfunding with a huge or unreasonable goal—particularly given the generally small donor base in the arts in Canada.

The AGO started with a massive crowdfunding goal: $1.3 million. “As a crowdfunded project, that would be right up in the top couple of percent” of projects, says FundRazr CEO Daryl Hatton. “I recommend they start with smaller pieces.”

The smallish nature of the arts donor base in Canada is also a factor to consider when setting initial crowdfunding targets. “I suspect part of the challenge is you’re dealing with a fairly small segment of the population who follows art, particularly modern art or abstract art,” says Carleton University philanthropy and non-profit leadership professor Susan Phillips. “And it’s hard to convert those who either don’t appreciate or just don’t know about this particular giving space.”

It’s good to look at other international museums for scale expectations. The Louvre has done big, $1 million-plus crowdfunding campaigns before—but it is reportedly the most visited museum in the world at 8.1 million visitors per year, with a much larger base to draw upon. The Smithsonian, which gets 30 million attendees per year across all its museums, did its first big crowdfunding campaign in 2015—and even then, it only looked to raise “$500,000 for work on the space suit Neil Armstrong wore in 1969 when he walked on the moon,” the Washington Post reports.

By comparison, the AGO had just under 1 million visitors per year in 2016–17. And yet it sought to crowdfund $1.3 million in 30 days. It’s possible that reviewing that goal in advance—or at least setting the fundraising period at 60 days, like the Louvre has for its latest crowdfunding campaign, or working directly with crowd funding experts to choose an appropriate campaign object, target, timeline and goal—which the Smithsonian did with Kickstarter—would have generated more success.

3. Do consider social media and audience reach for your project as a plus.

In many ways, a Kusama was the right artist to pick for an AGO crowdfunding campaign. Ticket demand and social media mentions to the show were very high for the AGO’s Kusama exhibition this spring, and Kusama has been called “perhaps the most Instagrammed artist ever”—so when generating online donations, it seems like more of a lock than a lesser-known artist.

“It was the right campaign for the right issue,” says Paul Nazareth, VP education and development at the Canadian Association of Gift Planners, of the AGO’s Kusama crowdfunding effort. “That’s because the AGO is the largest organization of its kind [in Ontario] and that exhibit had the most amount of human volume. The things that line up to be solid on crowdfunding is you have to have high volume, high engagement, things like Instagrammability—and this was the largest Instagram event in Canada in some time.”

The AGO saw more than 165,000 visit the exhibition—with both visiting and not visiting being motivations for some donors. “During the campaign, we received a wide range of feedback regarding Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors,” says an AGO spokesperson. “Several #InfinityAGO donors told us they donated because of the wonderful experience they had at the exhibition and that they wanted to share this experience with the wider community. Others, who couldn’t get tickets to the exhibition, told us they chose to give to #InfinityAGO as a way to get—or give—guaranteed early access to see the work.”

4. Don’t mistake social media mentions and reach for wholly positive audience experiences, for wholesale delivery of public good, or for easily converted donors.

When the AGO started posting about its #InfinityAGO campaign on Facebook and Instagram on November 1, it repeatedly received cogent critical comments from some users about its Kusama exhibition in the spring, as well as its decision to crowdfund for a Kusama for the future. These comments revealed, as well, how some audience members who care about art and the AGO feel concerned about the institution’s sincerity in advancing the public good.

On a November 6 donations call on Facebook, for instance, Sue Martin, an AGO member, posted a long and nuanced statement of her concerns and reasons for not donating, including the difficulty getting tickets for the original Kusama show. Her experiences had made her skeptical of the AGO’s commitments to access and inclusion.

“As a person with a disability,” Martin commented on the AGO’s Facebook post, “I couldn’t wait in line and do what was requested. I wrote explaining my situation and didn’t get a response other than to be told that lots of people were disappointed.” She adds in an email to Canadian Art, “Access is not only a matter of what happens within an exhibition, but it is about how tickets might be obtained, about how meeting space is possible inside the main door (all chairs have recently been removed), for there to be coffee shops without the requirements to carry trays, how people should be treated, and for there to be regular spaces for patrons to remove themselves from sensory overload and—above all—for this to be normalized.”

Kapil Vachhar, a graphic designer and frequent AGO attendee, also left a critical comment on an #InfinityAGO Instagram post last month. In a call with Canadian Art, he says his experiences at the Kusama exhibition and with the recent social media campaign left him concerned about the gallery’s commitment to art and social issues, rather than Instagram-friendly experiences.

Vachhar says that he found the AGO’s Kusama show in the spring glossed over the way the artist uses her work to “deal with the trauma in her life everyday” and that “it was a really good opportunity to bring those [trauma and mental health] issues into focus,” but that opportunity was not fulfilled. Instead, he says, he saw the AGO as more interested in creating an Instagram-focused, “Happy Place”–style visitor experience.

“You have a lot of people’s attention,” Vachhar says of the AGO’s Kusama show. “Why don’t you use it for something more than making money? Are you an art institution or are you a business? You have to make up your mind.”

Crowdfunding experts also point out that, audience opinions aside, it is also challenging to convert social media reach to donations in the current Facebook and Instagram environment.

“Crowdfunding is a lot like e-commerce in that you’ll get 100 people to visit the campaign, but maybe only 1 to 3 of them will actually contribute,” says Darryl Hatton, CEO of FundRazr. “And on Facebook, if you’ve got a Facebook group or a Facebook page, and you want to get your post in front of all those people, you are going to have to pay for [it]—your default visibility now is 1 or 2 percent, unless you pay to boost a post.”

5. Do align your crowdfunding cause with your mandate.

In early conversations about the Kusama crowdfunding campaign, AGO CEO Stephan Jost made the argument that Kusama’s place in the art-historical canon needs to be recognized.

“It’s really hard to talk about things like minimalism, pop art, and performance art together,” Jost told Canadian Art in addressing significance of Kusama’s work to the AGO permanent collection. “They’re always seen as three separate things from the ’60s and ’70s. But Kusama is the only artist who really brings those things together. You can make the argument that Warhol is really important that way too, but I don’t think art history in the ’60s and ’70s makes sense without Kusama. We have major Judds and Warhols [in the collection], but if I dare say, there is also the history of gender bias to deal with.”

To that point, the art-historical argument for acquiring a Kusama was strong.

6. Don’t ignore who or what within your mandate has the greatest need, or what parts of the mandate are being ignored.

One of the key criticisms that the AGO received on social media and elsewhere after announcing that they were fundraising $1.3 million for a Kusama was that the money could have better gone to Toronto, Ontario or Canadian artists.

“I understand that obviously there’s a lot of famous artists I want to see the work of,” says AGO attendee Vachhar. “Like, I want to see a Picasso; I want to see a Kusama. But if you are spending $2 million to buy that piece instead of giving something to a local artist…. Well then, you are not nurturing your regional artists to ever reach the level of a Kusama or a Van Gogh.”

Vachhar says his views on this topic have been shaped by regular volunteer work at Sketch, a Toronto community arts enterprise for youth who “are navigating poverty, living homeless or otherwise on the margins,” says its website.

“You go in every week [to Sketch] and meet these artists who are doing fantastic work but never get gains from it,” says Vachhar, and the frustration grows. “I understand why the AGO would [acquire a Kusama] as a business decision: this is probably a good catch for them. But to invest $1.3 million in an artist that’s already extremely successful, and who lives in Japan, a country really supportive of its artists.… well, it seems insulting that you would spend this much money on someone who doesn’t really need it when you own local community is significantly struggling.”

Susan Phillips, at Carleton, also notes that the AGO has tended to focus more on Toronto in its fundraising and outreach than on other areas of the province which gave it its name (and, it must be said, its public funding).

“I think a question is: To what extent is [the Kusama] seen as something that benefits those who don’t live in Toronto?” Phillips asks. “How much can it be seen as something that is a treasure to the country, or certainly the province, as opposed to the city?” Though the AGO cited donors from Hamilton and London in its final campaign roundups, “I suspect there is a significant lack of awareness beyond the metro region,” says Susan Phillips, of both the AGO Kusama campaign, and, more broadly, of what the AGO has to offer Ontarians at large.

7. Do heed well-established crowdfunding conventions—post a video and artist information right off the bat, and have well-calibrated reward levels.

Part of what some crowdfunding experts found curious about the AGO’s Kusama campaign was that it withheld images of the artwork in question until halfway through the campaign.

“Certainly having a video is essential,” says Douglas Cumming, a Canadian finance professor who is co-authoring a forthcoming book about crowdfunding. “Definitely do that before the campaign is even started. And tell people more about the artist. Get people excited.”

Cumming also has concerns about the rewards structure of the AGO Kusama campaign compared to the hundreds he has studied as an academic.

“The rewards levels could be way better,” he says, looking at the #InfinityAGO page earlier this week. (As of press time, the rewards section has now been removed.) “I would describe these rewards as being small compared to the size of the contributions…. Like up to $99 you only get two tickets and a button? What does a button cost to make, 10 cents? You wouldn’t do this for the reward levels, basically.”

The fact that the AGO usually deals with high-net-worth donors, rather than with everyday folks, might have influenced the poor reward choices.

“The second-highest reward level, $5,000 is pretty serious,” says Cumming. “You have to be uber-wealthy to treat that as a quick investment. Normally people want something more than an umbrella or a pin. At $99, I could buy a ticket to a concert.”

8. Don’t obfuscate about what will happen if you don’t reach your crowdfunding goal.

Clarity about what happens when a crowdfunding goal is not reached is essential, says Cumming. And such information was not clearly highlighted on the main #InfinityAGO donor page when he looked at it earlier this week.

“On Kickstarter you must reach your goal, otherwise they give the money back [to donors],” says Cumming. “On Indiegogo you can elect to keep the money you raised regardless of whether or not you give it back. And for people in the crowdfunding community this difference is very big and important: I would want to know, if you don’t reach your target what happens to the donation?”

Asking donors to give without knowing whether the project will actually reach fruition, or whether they will get money back, puts the risk on the donors’ shoulders, rather than the institution’s shoulders, says Cumming. And in fact “all or nothing” projects tend to be the more successful ones in the crowdfunding world in general: “Normally a project like this would done [as] all or nothing,” says Cumming, in his opinion.

Given that the AGO clearly had plans to go ahead with the purchase in any case, but did not make that clear from the get-go, is unusual. “For their own confidence, it’s a good thing that they had it in their back pocket,” says Daryl Hatton of FundRazr. But: “They were not being straightforward…I like the transparency model myself, and social media is very much about transparency.”

9. Do use tax receipting as a reward if it’s available to you.

One advantage many charities and non-profits have over other organizations that might be crowdfunding is that they can offer tax receipts as a donation reward.

Paul Nazareth, VP, education and development at the Canadian Association of Gift Planners, thinks that the AGO did an effective combination of this kind—offering tax receipting for old-school, large-donation funders and doing other rewards for younger, smaller-donation funders.

“They did proper two-step fundraising,” says Nazareth. “One which skews younger donors connected to digital and social, as well as a traditional campaign with tax receipts that talked to high-level donors.”

10. Don’t be stingy about the tax receipting, or at least make it be clear from outset who gets what.

When the #InfinityAGO campaign was launched on November 1, it stated that only donors at $100 or above would get a tax receipt. But later, it clarified, in smaller print, that donors at $25 or over could get a tax receipt in lieu of a ticket to the Kusama Infinity Room this spring.

This contrasts with the Louvre’s approach on its current crowdfunding campaign to restore an arch outside the museum. Regular admission to the Louvre is 15 euros, and its current campaign states that “For €30 or more (or €10.20 after tax deduction), donors will receive an invitation for two people to visit the Musée du Louvre for free.”

In the AGO campaign therefore, at least its original design, people had to give five times the normal admission price to get a tax receipt. But at the Louvre, they only had to give two times the normal admission price for the same. And they didn’t have to sacrifice ticket benefits to do so.

11. Do be willing to learn, grow and be responsive.

The AGO did switch up some of its “rules” along the way of #InfinityAGO when it realized it had mis-stepped. Though originally it said it would reveal the Kusama Infinity Room only when all the funds had been raised, it revealed it a few weeks in instead. And though it left the $25 tax receipt option in fine print, it did at least make that adjustment eventually.

“From the beginning, we knew that that the campaign would need to be nimble and flexible,” says an AGO spokesperson. “We had no playbook by which to guide our decisions. We opted to reveal the room at the end of the third week, because we believed it would help galvanize support and give people a sense of what they were coming together to create. It achieved that.”

12. Don’t ignore the costs of making a crowdfunding project work.

With Facebook having changed its algorithm to incentivize purchasing of paid posts, it’s more costly than ever to run a successful crowdfunding campaign. There are other costs to consider in making a campaign successful too.

As the Washington Post reports,

“The Smithsonian’s [crowdfunding] projects beat the odds, but they cost a lot to produce, and those expenses were built into the campaigns. “Reboot the Suit” sought $700,000 from the public, significantly more than its $540,000 budget. Although a Smithsonian fundraiser originally said the costs were about 8 to 10 percent, they ended up topping 17 percent.”

“Keep Them Ruby” was even more expensive. Records show for every $100 donation, the Smithsonian spent $38 on the costs of the Kickstarter project, including the video, rewards and Kickstarter’s fees, leaving $62 for Dorothy’s slippers.

“A lot of organizations get excited because they think it’s cheap and easy. Cross that out. It’s neither cheap nor easy,” said Lucy Bernholz, director of the Digital Civil Society Lab at Stanford University, of crowdfunding projects.

13. Do leverage matching-fund initiatives and events like #GivingTuesday where applicable.

At a few points in the campaign, the AGO offered matching funds as an incentive, and it also made a push on #GivingTuesday with matching funds as well.

“#GivingTuesday is the single largest day for online fundraising, so that was a smart move,” says Paul Nazareth. “And they got matching funds—it’s a big dirty secret in fundraising, but the matching funds really do help.”

14. Don’t overlook the long-term consequences of your short-term crowdfunding decisions—and don’t assume crowdfunding is a silver bullet, especially for museums and galleries.

Looking ahead, it will be interesting to see how the AGO’s crowdfunding attempt pans out in the long term. No living private donor came forward to make up the roughly $650,000 final Kusama shortfall, nor the $1 million starter investment, despite the large number of wealthy people on the AGO’s Board of Trustees. Instead, the shortfall was made up from an existing acquisitions fund created by a decade-old bequest.

Does this mean that the AGO’s current cadre of high-net-worth donors and trustees had issues with this recent crowdfunding attempt? Was there a line drawn here in terms of being willing, or unwilling, to act as a white knight for the administration’s own hubris? How will that play out in the future? Only time will tell on these points. But they are worth considering.

Overall, crowdfunding should never be viewed as an easy solution for museums and galleries, says Paul Nazareth.

“I feel strongly that I don’t think it’s the right thing for most charities and boards,” he says. “Most museums don’t have the public engagement necessary to do this kind of fundraising.”

If a Canadian museum does want to proceed with crowdfunding, says Nazareth, “they need to consider the platform, the costs to launch and succeed, the fact that it’s not a regular donation and outside their usual methods and mandates, and that it’s not a silver bullet…it’s a high-profile and high-risk fundraising game.”

The idea of scaling up donations, and scaling up viewership, needs to be well-managed once the Kusama artwork is permanently installed, too, says AGO attendee Kapil Vachhar.

“Art is rarely built to scale up,” says Vachhar. “Picasso didn’t think his paintings would be viewed by 500 people at the same time…so I think at some point the AGO needs to invest not just in showing the art, but in making sure it’s a good experience. The lines were 45 minutes for those Infinity Rooms in the spring…I’m empathetic to the gallery, but it has to solve those problems, and not just make it seem like they are making a quick buck.”

A number of typographical errors in this article were corrected on December 7, 2018, including the spelling of Daryl Hatton. A clarification as to the nature of the Hodgson Fund was added on December 11, 2018.