1989 marked two significant events in Canadian art history. The Diasporic African Women’s Art collective (DAWA) organized “Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter,” a travelling exhibition of works by African diasporic women—the first of its kind in Canada to be organized by and feature artwork from all Black women. It was an effort to take up spaces that had, until then, been unavailable or in which Black women had been under- or mis-represented. That same year, the Royal Ontario Museum’s “Into the Heart of Africa” exhibition, which displayed African artifacts in a manner that glorified colonial exploits, led to protests and pickets by members of the Black community, some of whom came together and formed the Coalition for the Truth about Africa to demand the show’s closure.

These kinds of actions were commonplace in radical activism during the 1980s and 1990s, when Black and queer creative labour and activist practices were full of strength, spirit and energy. When Black women artists organized to make their material practices visible, they established their historical presence in the nation and its history of art, in defiance of cultural policies that had until then strategically prioritized European cultures and cultural production. Queer and African-diasporic communities were coming together to condemn the structural racism commonplace in arts institutions large and small, and to value Black arts and culture. Cultural critics like M. NourbeSe Philip and Rinaldo Walcott, magazines like At the Crossroads, WORD, Tiger Lily and This Magazine, and festivals like CAN:BAIA (Canadian Artists Network: Black Artists In Action) and CELAFI (Celebrating African Identity) were creating platforms to present and document Black creative practice. The Black Action Defense Committee, a precursor to Black Lives Matter Toronto, was formed in 1988 by Dudley Laws, Charles Roach, Lennox Farrell and Sherona Hall following the death of Lester Donaldson; it’s one example of activists’ response to the ongoing violence of the Toronto police toward racialized people.

There is, unfortunately, some cultural amnesia around these struggles and their methods. Such histories—of Black, queer, feminist radical political action—exist in word-of-mouth stories passed down from elders and through the friends and family of those involved. I grew up hearing these stories; within communities, however dispersed, these pasts and participants are known. But there are few public archives of these events—especially those that focus on the use of art toward action and social change. One could even think they don’t exist at all.

But they do exist. In 1866, just a few years after BC provincial governor James Douglas, who was of African descent, called on Blacks from California to come north to settle on Vancouver Island, the British Columbia Chronicle reported that a small group of people held an “exhibition by colored children” as a way to “raise funds to establish a Public Library for the colored people of Victoria.” Across the country in Windsor, Ontario, Mary Ann Shadd had just finished publishing the Provincial Freeman, an anti-slavery newspaper. Documentation of our innovative ways of using creative practice to organize for change is too often lost, too often disregarded by historical narratives.

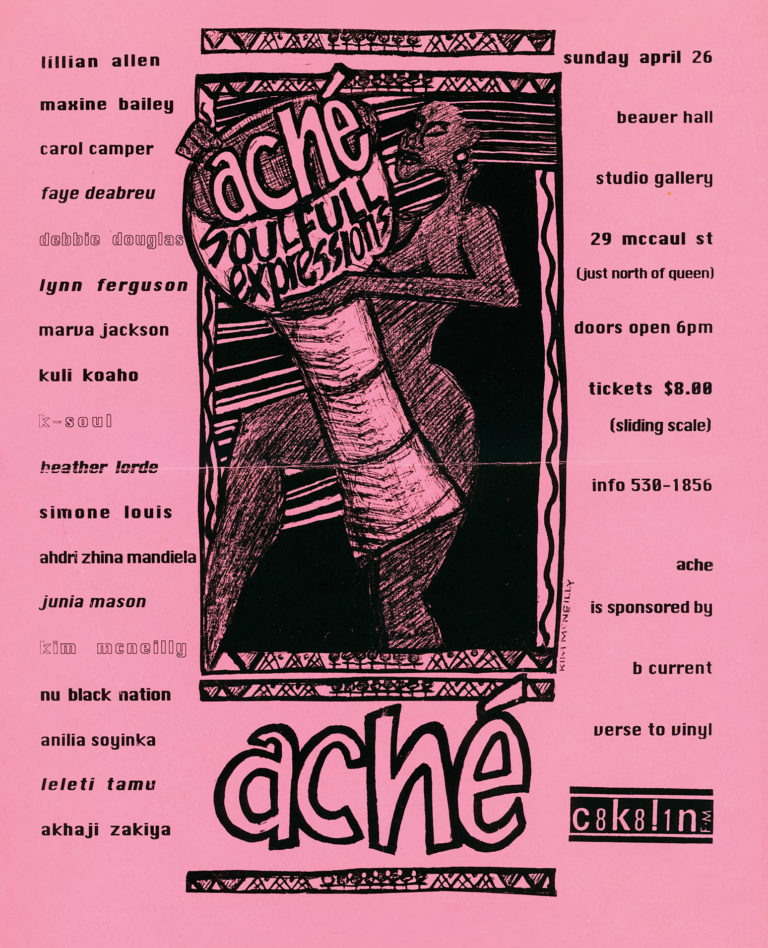

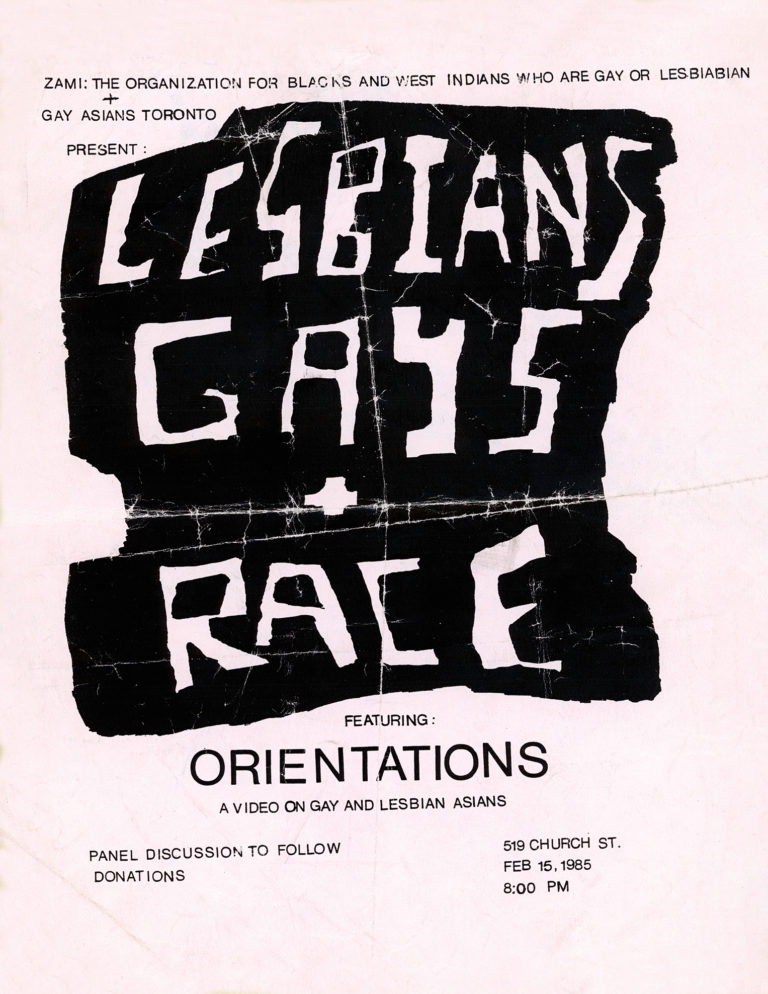

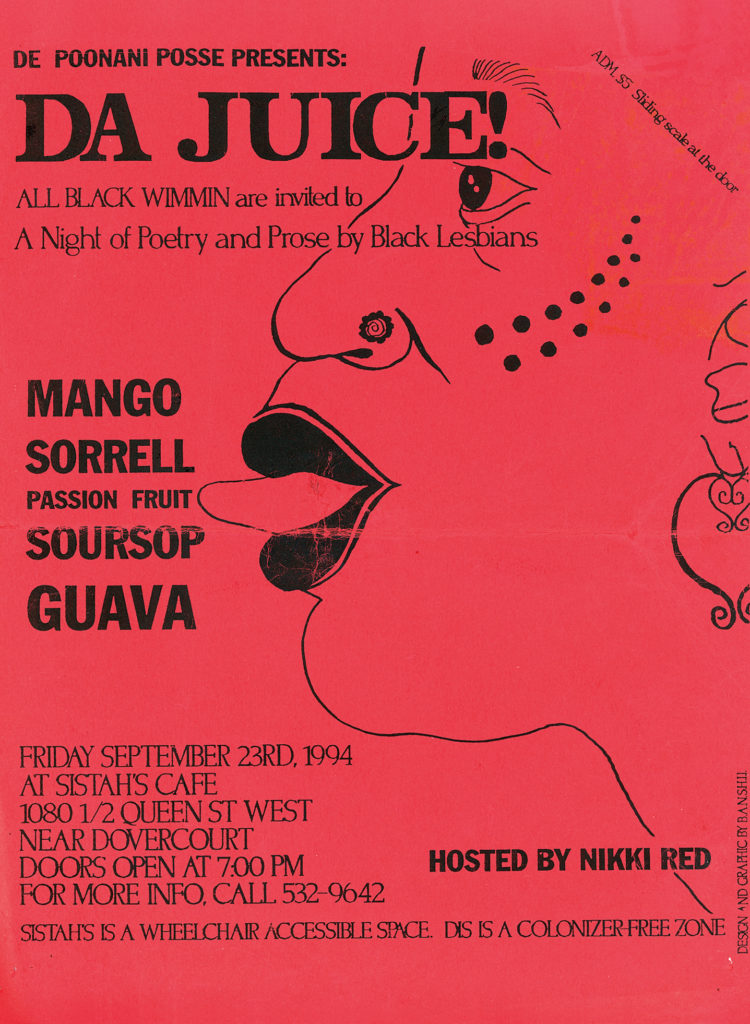

Poster courtesy the Arquives.

Poster courtesy the Arquives.

Poster courtesy the Arquives.

Poster courtesy the Arquives.

So, it was with relief that, earlier this year, Black communities received the exhibition “Legacies in Motion: Black Queer Toronto Archival Project,” at BAND Gallery in Toronto, for which poet and activist Courtnay McFarlane assembled an archive of Toronto’s Black queer activism from the ’80s and ’90s. On the walls were book covers, posters and pages enlarged from Black, feminist and queer magazines of the time, such as Xtra, At the Crossroads and Our Lives. Most of the posters were printed in black on coloured paper—a cost-effective approach that had a stunning visual impact. In one room was a series of bookshelves with poetry, fiction, history and theory by Black thinkers. In the next room were large portraits of Toronto’s Black queer community of activists and organizers, and a table with several binders full of similar photos. One nearly floor-to-ceiling painting on masonite by artist Grace Channer—my co-parent from the age of four—rested in a corner of the largest gallery. In black, brown, red and yellow hues, it shows two women embracing amid painted swirls of homophobic slurs written in loose, large brushstrokes. Channer’s visibly hand-drawn touch is similarly reflected in the strong lines and sensuous curves of the drawings and illustrations on T-shirts, posters and pamphlet covers throughout the show. They are simple drawings: symbols and text in celebration, calls to arms mixed into collages.

At the time, Black queer creative practice was an act of theorizing and world-building that was collective, and decidedly anti-capitalist in nature. Channer remembers how “doing activist work was so exciting because we were constantly thinking, constantly processing and constantly theorizing. Everybody was talking and everybody was contributing and arguing. Whatever the issue was, there was a lot of process work that allowed us to have radical ideas and radicalize what doing art practice was, and what it was as a thing that’s pushing forward the desires and theoretical discussions of a community.” The aesthetic of their practice needs to be seen, read and understood with a different set of critical considerations than those used for “canonic” Canadian art. They share something with what scholar Richard William Hill identified as the themes of “cultural revival, colonial critique, and institutional access” of Indigenous artists in the art world around the same time. (In 1992 “Indigena,” curated by Lee-Ann Martin and Gerald McMaster at the Canadian Museum of Civilization—now the Canadian Museum of History—was a rare instance of a group exhibition curated exclusively by people of Indigenous heritage and containing all Indigenous-made artworks.) Throughout the 20th century, art and culture from these communities were regularly discussed by mainstream critics in opposition to the visual and social narratives applied to European-descended artists—like those in the Group of Seven, for example.

Organizing the recent archival show, McFarlane says, “was about recognizing that there were things we were doing back in the day that are connected to things happening here, now.” McFarlane was an active organizer in the ’80s and ’90s, and is still engaged with social work, including as a co-founder of Blackness Yes!, the original organizing group of Blockorama at Toronto’s annual Pride celebration. Community members like McFarlane, Channer, Makeda Silvera, Karen Miranda Augustine, Debbie Douglas, Douglas Stewart, Angela Robertson, Junior Harrison, Nik Redman, Steven Lungley and Trevor Gray (some of whom shared their archival materials, objects and mementos for the exhibition) all worked alongside each other to use creative practice and education against police violence, poverty, racism and homophobia. Aesthetic choices for texts, images and symbols were arrived at through discussion; the gestural traces of the drawings and posters revealed the involvement of one, or sometimes several people and styles. “You would bring whatever skills you had,” McFarlane remembers. “So if you were an organizer, if you were a writer, if you were a visual artist, if you were a dancer, if you had a connection to the government or funding… you just brought your skills and your interests. Sometimes it wasn’t even skills or interests you had—because the skills were things you were developing as you did the work. And it was an opportunity to actually use these skills, or use some of these abilities, toward a cause, or toward a group.” The artworks they created somehow contain the discussions they had during creation, and the spirit and energy of all the people who contributed. Creative practice was manifest from collective theorizing and sharing ideas—it was a process of thinking.

Poster courtesy the Arquives.

Poster courtesy the Arquives.

On all fronts, gay, lesbian, trans people and feminists were joining to create events, share resources and organize for change. The effort was to work together as a group toward a goal—a vision of a different world. During all-night banner-painting sessions, arguments over what language and wording to put on posters, negotiations on the choice of drawings and prints for T-shirts or pamphlets, there were conversations that generated theory and shaped actions to come. Collective creative labour toward activism was not only anti-capitalist; it was about the community rather than the individual. The feeling of making and the feeling of care and the feeling of pride that charged these activities are visible across the works and materials of the “Legacies in Motion” exhibition. One gets a distinct and palpable sense of who these communities were and what they were about from looking through the aesthetics of this archive—the hand-printed T-shirts or the detailed, hand-lettered posters. “It was just things we were doing because we recognized what needed to be done,” McFarlane says. Beyond simply the resourceful and enterprising manner in which these practices were undertaken, this collection of events, organizing and mobilization, all this work testified to a commitment to equity in all its possible manifestations.

Sadly, at the time in which they were created, the contents of the exhibition would not have been perceived as contemporary art. Presenting the objects and material archives of Black queer activism in a gallery context in 2019 raises questions about how this work has been historically valued, and prompts a reconsideration of the significance of the creative approaches that enabled it. Interest in the aesthetics of activism has increased over time. There has been a marked shift in the terms of inclusion—what were previously seen as oppositional aesthetics are now central to many art industries. The margin has been conditionally called in; activist art and collective making have become de rigueur. Furthermore, these types of practices have become codified in a formalized artistic language. The danger now is that activism-as-creative-practice is becoming mere veneer.

The works they created somehow contain the discussions they had during creation… Creative practice was manifest from collective theorizing and sharing ideas—it was a process of thinking.

“I think in general there are ways that artists now are trying to tap into the interest in activist practices,” says Syrus Marcus Ware, an artist who is known for his activist art. “And so you see people making work or dropping into a community with no prior connection, and no prior work for the community, then doing something for six weeks or even for six months, and leaving.” With this embrace of activism has come a tendency by contemporary artists to co-opt an aesthetics of activism without necessarily understanding its core values, or what it means to be immersed in and dedicated to a cause. Indeed, activist labour goes beyond a look and feel—it’s durational, it’s on the ground and it’s involved. “If one is going to make work that is rooted in social justice,” Ware continues, “it should actually be connected to a movement and be connected to organizing and not just the aesthetics of activism without a rooted practice.”

McFarlane’s archival exhibition presented a particular kind of artwork that operates beyond the visual symbology through which ethnic arts are understood. The practice itself, of working together, was the aesthetic—it was one concentrated on collective endeavour, and not necessarily free of conflict. The goal was the event: participants were not overly worried about remuneration or selling products or personal branding. Looking at the histories of Black artistic practice is a way to open up new understandings of activist art as a testament to its time. Creative labour of this sort was about ideas, and about everybody being there together and sharing those ideas. In the lines and shapes of the works, we see the traces of conversation that happened, and the full breadth of what engendered it.

Things have changed significantly in the time since, but many of the initiatives that began in the ’80s and ’90s, and the folks involved in them, continue today. Although some figures and organizations have passed, like the great activist Sherona Hall (1948–2006) or the Sister Vision Press (1985–2001), other groups have become institutions in their own right, like the still-active Black CAP (the Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention), founded in 1989. But what is important to remember, perhaps specifically in the context of painting, and for a whole lot of ephemera and archival material that may or may not have been kept, is that these practices were about more than just the work. They were a way of making, a method, that is in itself significant. It helps define what creative labour is, why it matters, and how it persists in certain kinds of Black queer collective organizing, even if the specific art forms have changed. Thinking about an aesthetic of Black Canadian activist painting, and history, means using different parameters to assess it. One must look differently.

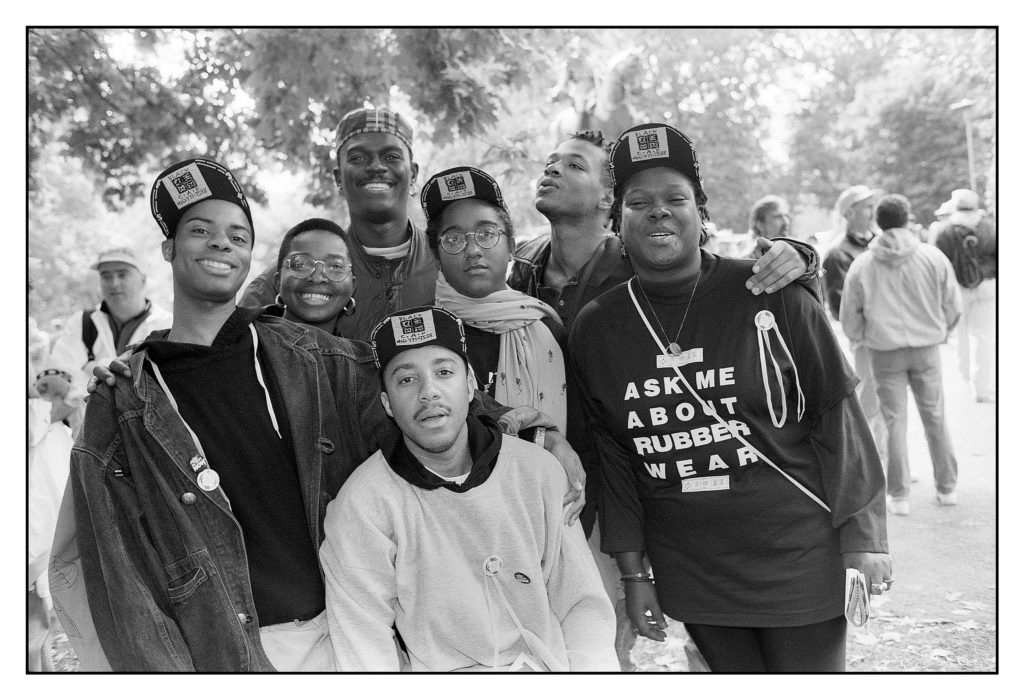

Black CAP (Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention) members (clockwise from left) Courtnay McFarlane, Angela Robertson,

Stefan Collins, Dionne Falconer, Bentley Ball, Cecelia St. Louis and D avid Harrison at AIDS Walk in Toronto in 1991. Photo: Steven Lungley.

Black CAP (Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention) members (clockwise from left) Courtnay McFarlane, Angela Robertson,

Stefan Collins, Dionne Falconer, Bentley Ball, Cecelia St. Louis and D avid Harrison at AIDS Walk in Toronto in 1991. Photo: Steven Lungley.