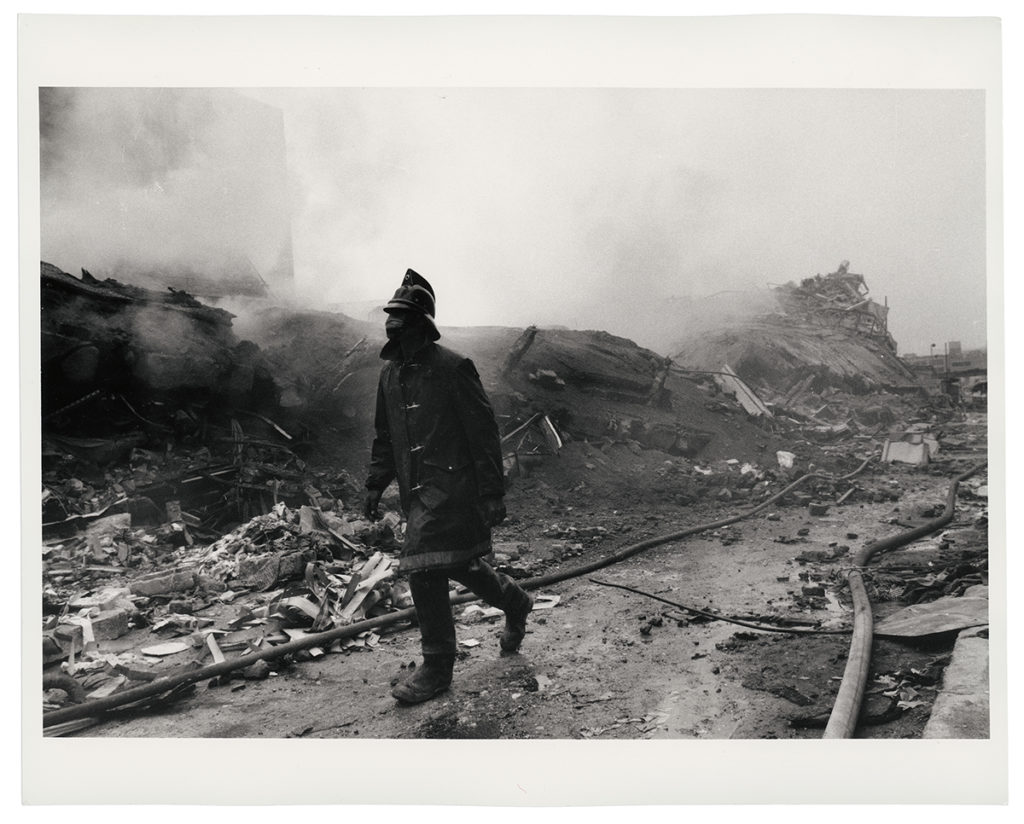

A fireman strides down a muddy, debris-strewn street, past heaps of smoking wreckage, wearing a mask to filter particulates from the air. A shirtless child reclines on their back, thin arms splayed out at their sides, ribs rising visible under the skin of their chest.

These two images could easily be mistaken for some of the photos currently circulating in news and social media regarding California wildfires and Yemeni starvation, respectively. But they are actually historical photographs—each part of exhibitions at Toronto’s Ryerson Image Centre that take a closer look at crisis photography, as well as this art form’s complex trajectories and implications.

“The tropes are constant,” says Paul Roth, director of the Ryerson Image Centre, of the ways that photographers and their media outlets often present disaster stories. “And they’ve been around for as long as the period of photography that I’ve studied.”

Together, the two major exhibitions on at the RIC—“Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story” and “Terremoto: Mexico, 1985”—re-present and re-examine historical photojournalistic images of disaster. On until December 9, these shows suggest how images can only ever tell a limited version of a story, and also, at the same time, demonstrate how complicated photo-based narratives can be.

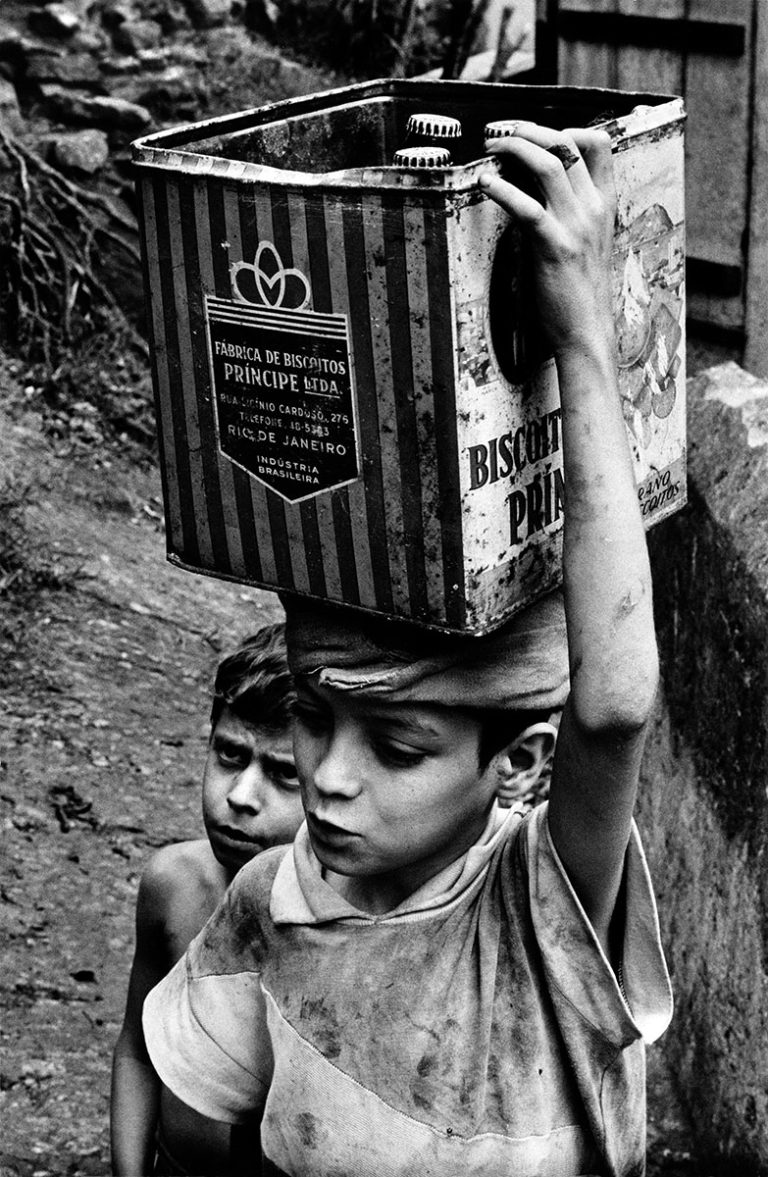

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation.

Rafael Goldchain, Untitled (Earthquake Ruins, Mexico City), 1986. Ryerson Image Centre, gift of Howard and Carole Tanenbaum, 2017.

Rafael Goldchain, Untitled (Earthquake Ruins, Mexico City), 1986. Ryerson Image Centre, gift of Howard and Carole Tanenbaum, 2017.

“The Flávio Story” examines a 1961 photo essay that American photographer Gordon Parks—the first Black staff photographer at Life magazine—did about a Rio de Janeiro favela boy, Flávio da Silva, and his impoverished family. The image of a child on their back, described at the beginning of this article, was shot by Parks of da Silva, and is in the exhibition.

The show also documents the decades-long fallout from that 1961 photo essay and its reader response. “That photo essay Parks did for Life spawned another photo essay, and that spawned a counter photo essay, and that spawned a film and a book,” says Amanda Maddox, co-curator of the show and assistant curator of photography at LA’s Getty Museum, where the “The Flávio Story” is headed in 2019. This uniqueness was part of what drew Maddox to it when the Getty was looking to acquire some work by Parks that hadn’t been extensively studied before. Says Maddox, “The exhibition grew out of an acquisition.”

Parks, within and beyond “Flávio,” is also notable for having developed or popularized some of the ways that crisis is depicted in contemporary photography. “Gordon Parks was such a fantastic image-maker,” says the RIC’s Paul Roth, who also co-curated “The Flávio Story,” and curated and wrote on Parks’s work in the 1990s and 2000s. “He is one of the definitive figures in the making of those image tropes.”

The “Flávio Story” exhibition goes to some lengths to illustrate the multiple lives, and myths, of Parks’s depictions of Flávio da Silva. The exhibition documents how, after Flávio da Silva first appeared in Life in 1961, magazine readers sent thousands of dollars in unsolicited donations to him via the publication. Life in turn helped da Silva move to the US for asthma treatment, and purchased a new home for the da Silva family in Rio, resulting in another, decidedly more sunny, Life photo essay also exhibited at the RIC. Meanwhile, Brazilian magazine O Cruziero hired photographer Henri Baillot to shoot a counter photo essay of dire poverty in New York, with some of Baillot’s shots directly mirroring those Parks shot in Rio’s favelas. (A room in the RIC exhibition is dedicated to this counter essay.) Eventually, Flavio was forced to move back to Brazil, though he said he wished to stay in the United States, as the exhibition texts indicate.

In later years, Gordon Parks and Flávio da Silva continued to be connected, and when they last met on camera, for a documentary about Parks’s life, the fiftysomething da Silva was living in a shack behind his family’s Life-purchased house, doing occasional construction and labourer work. Film and photographs from this time also appear near the end of the RIC exhibition. Notes and documents from the Gordon Parks Foundation, which collaborated on the show, as well other photographs such as those showing Parks travelling with da Silva to the US in the early 1960s, further demonstrate the complicated relationship Parks had to this boy-turned-man and his life story.

Paulo Muniz, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation.

Paulo Muniz, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1961. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1999. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1999. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation.

The other major exhibition currently on at the RIC is “Terremoto: Mexico, 1985.” That show presents press photos—many from the RIC’s own Black Star Collection—shot in the aftermath of the 1985 Mexico City earthquake that killed some 10,000 people and left 250,000 homeless. The photos include Pedro Meyer’s Smoke Swallower, the black-and-white shot of a firefighter striding across a smoky, detritus-strewn landscape described at the beginning of this article.

“All these photographers found themselves part of the [earthquake] disaster during the aftershocks,” says Denise Birkhofer, collections curator and research centre manager at the RIC, and curator of “Terremoto.”

Even though photos from this earthquake were bylined individually, they were often a result of group collaboration. “They ended up working in this really collaborative way,” Birkhofer says of the photojournalists in Mexico City in 1985 following the earthquake. “They were sleeping on each other’s hotel room floors, they were helping each other transport film to the airport or lending each other equipment.” One of the pictures in the show, for instance, shows Barbara Laing wearing a hard hat lent by another photographer.

Although crisis photography does fit into repetitive tropes at times, curator Birkhofer nonetheless found herself intrigued by how photographers covered the same crisis differently: “Pedro Meyer was working in a more documentary mode, but his photos are poignant, with titles that were symbolic, in a way,” says Birkhofer. “Whereas Barbara Laing’s photographs are all focused on a human subject.” Some other “Terremoto” photographers used humour more frequently in their work, she notes, while Toronto-based photographer Rafael Goldchain used medium-format rather than 35mm film.

Some styles also stayed consistent across several decades of earthquake coverage—between the 1985 earthquake and another major one in 2017, for instance. “One thing that was interesting [in curating the show] was to see how photographers last year were photographing the earthquake,” says Birkhofer. “Some were very young in 1985… but for 2017, they just used Instagram.”

![Barbara Laing, <em>[Grieving survivor], Mexico City, Mexico</em>, 1985.

Gelatin silver print. The Black Star Collection, Ryerson Image Centre.](https://canadianart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2-768x945.jpg) Barbara Laing, [Grieving survivor], Mexico City, Mexico, 1985.

Gelatin silver print. The Black Star Collection, Ryerson Image Centre.

Barbara Laing, [Grieving survivor], Mexico City, Mexico, 1985.

Gelatin silver print. The Black Star Collection, Ryerson Image Centre.

Rafael Goldchain, Earthquake Ruins and Soccer Celebrants, Mexico City, from the series Nostalgia for an Unknown Land, 1986. Chromogenic colour print. Ryerson Image Centre,

gift of Howard and Carole Tanenbaum, 2017.

Rafael Goldchain, Earthquake Ruins and Soccer Celebrants, Mexico City, from the series Nostalgia for an Unknown Land, 1986. Chromogenic colour print. Ryerson Image Centre,

gift of Howard and Carole Tanenbaum, 2017.

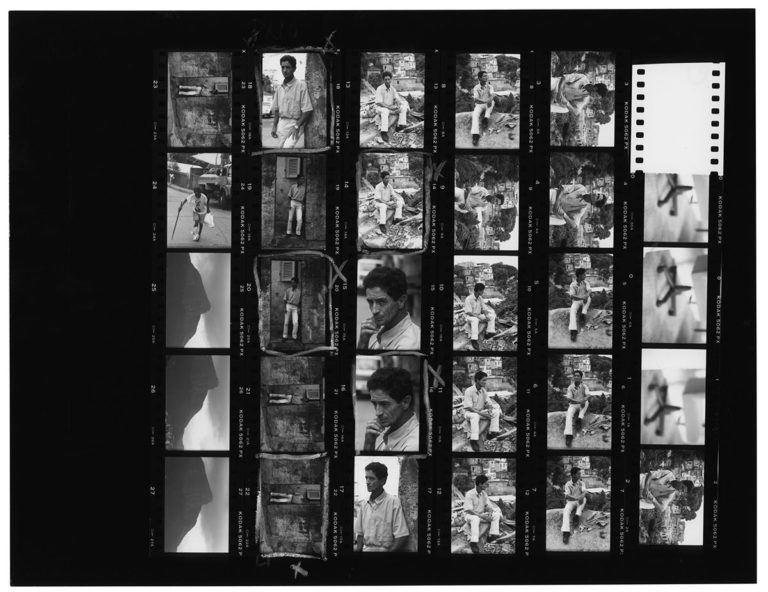

Contact sheets are included in both “The Flávio Story” and “Terremoto.” This foregrounds the range of photographs that were shot—and the fact that a careful selection process took place, often not even by the photographers.

“Once [Gordon] Parks’ negatives were delivered to Life’s New York headquarters,” says a “Flávio Story” wall panel, “film editor Peggy Sargent and picture editor Ray Mackland distilled dozens of images from fifty-three rolls he shot, to be printed by the magazine’s darkroom technicians. Art director Bernard Quint designed the story layouts, selecting, cropping and juxtaposing photographs and text to tell the story of Flávio da Silva and his family effectively across Life’s large page spreads.”

And in “Terremoto,” it becomes apparent that different media outlets shape the same photographic stories differently: “In the show you can see a how Paris Match and Time, for example, were presenting the [1985 earthquake] disaster in different ways,” Birkhofer says.

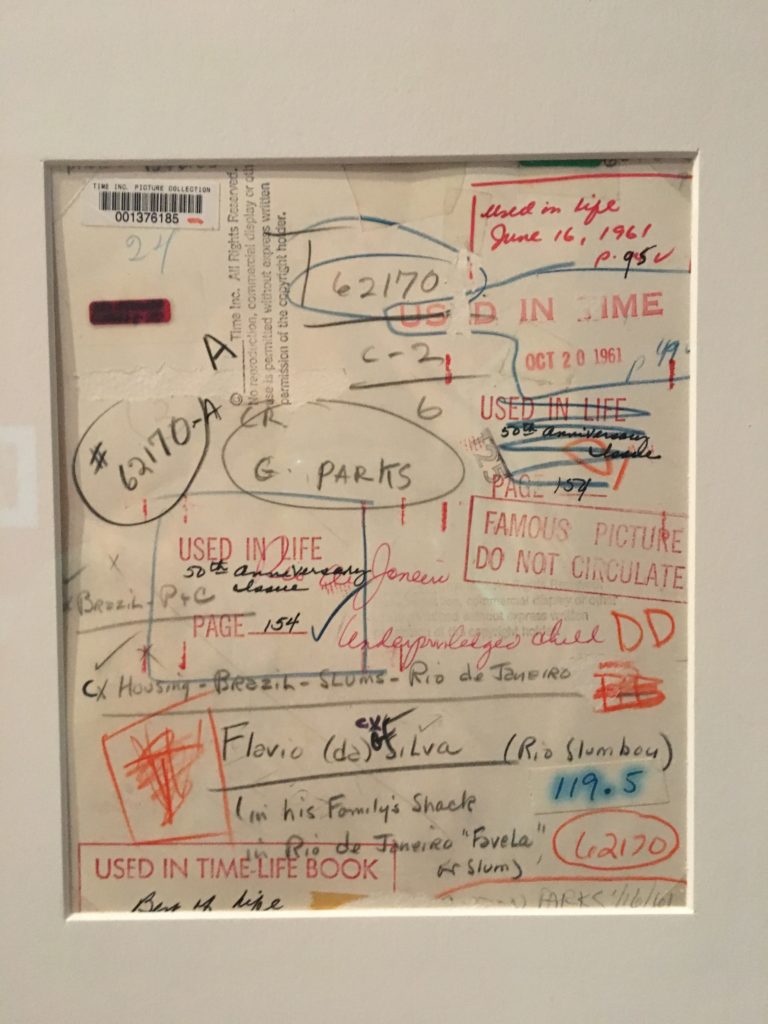

The fact that some crisis images get used and reused in different ways, and become part of a narrative shaped by many individuals, comes across in a single “Flávio Story” print that is framed to show both the front and back of the photograph. The back side of this Flávio photo is filled with handwritten texts and red rubber-stamped notices: “Used in Life 50th Anniversary issue, page 154”; “Used in Life June 16, 1961”; “FAMOUS PICTURE DO NOT CIRCULATE”; “USED in TIME-LIFE BOOK”; “Rio de Janeiro Underprivileged Child”; “Flavio (da) Silva (Rio Slumboy)”. The jumble of words also suggests just how messy and unplanned, clichéd and complicated the use of a single photographic image can be.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1999. Contact sheet. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation.

Gordon Parks, Untitled, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1999. Contact sheet. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation.

The reverse side of one of the Flavio images is displayed in the Ryerson Image Centre exhibition. Photo: Leah Sandals.

The reverse side of one of the Flavio images is displayed in the Ryerson Image Centre exhibition. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Ultimately, says RIC director Paul Roth, both “The Flávio Story” and “Terremoto” present the opportunity to understand storytelling in today’s mass media—and, in the age of the algorithm, social media too.

“It’s absolutely inevitable that things [like disasters] will be contextualized in a packaged, narrative fashion [via media] so that people can find their role, find their comfort zone, and also experience drama and fear in bite-sized chunks,” Roth says of contemporary crisis coverage. “That’s so the media captures and keeps attention, attention that it needs for their advertisers… It’s part of a set of traditions, a series of corporate machines.”

There is also much value in going back and analyzing past events to learn from them now. “From my perspective, shows like ‘The Flávio Story’ and ‘Terremoto’ are really interesting ways to go back in time and look at how a story was told,” says Roth. “If you take a viewer inside and outside the story, then there is the possibility, I hope, of the viewer finding their own place in that hierarchy and understanding how their psychology has been set into a series of patterns.”

“I would love for people to understand how complex photographic narratives are,” says Amanda Maddox of the Getty Center adds. “In the context of creating a photo essay or documenting an individual, there’s certainly more than meets the eye. I think this show attempts to unpack those complexities…. And to consider how complex representation of something can be.”

“Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story” and “Terremoto: Mexico City, 1985” are on view at the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto until December 9, with a tour led by Paul Roth taking place on November 21 at 6 p.m.

Pedro Meyer, Smoke Swallower, Mexico City, Mexico, 1985. Gelatin silver print. The Black Star Collection, Ryerson Image Centre.

Pedro Meyer, Smoke Swallower, Mexico City, Mexico, 1985. Gelatin silver print. The Black Star Collection, Ryerson Image Centre.