Sometimes I don’t know into what world I have woken up. It is as if I went to sleep in a pre-COVID time and awoke to a new future.

I scroll through my newsfeed and see abolition messages writ large across the city streets. I read about defunding the police in, of all places, Cosmopolitan, and my email is clogged with “solidarity with Black Lives Matter” statements from every bakery and soap store where I’ve ever spent $2.00.

We are in this strange period of transitions. We are at the beginning of a new world emerging post-COVID and we are at the beginning of people awakening to these activisms. We are in the middle of a revolution of our global consciousness and we are at the end of old systems like racialized capitalism. As the system changes, as Octavia Butler assured us it would, it is desperately trying to save itself, in part by positioning itself as part of the revolution. Hence my email is filled with these statements, the performative solidarities and demonstrative actions that do nothing to address the structural changes needed in this society for us all to live self-determined, free lives.

Perhaps the most perplexing, or perhaps most complex for me in these performativities, are the pro-Black/Black Lives Matter statements from arts organizations and institutions. I have worked in various arts institutions for decades and have been an artist for 25 years. I have witnessed first hand the anti-Blackness that is dyed into the wool of the arts. We have a white supremacy problem that is perhaps the art world’s best (worst?)-kept secret—this secret is something these solidarity statements do not address. Without addressing the larger systemic issues that plague the arts, what is the purpose of these statements?

Dr. Naila Keleta Mae, artist and assistant professor at the University of Waterloo, stated the following this week on Facebook:

I am disgusted by statements from institutions, corporations and organizations on what they plan to do about anti-Black racism in the future if they have done little or nothing to end it in the past. Their statements need to explain why they haven’t taken the horrors of white supremacy seriously even though they are well documented and centuries old. #blackandfree

Indeed, these statements fail to “explain why they haven’t taken the horrors” seriously; rather, they paint the institution as already doing the work. Meanwhile, the history of erasure and the shutting out of Black artists from mainstream—and yes, even from lefty art spaces—persists and cannot be separated in this moment of renewed support for “all Black lives.”

!Kona, co-founder and co-host of BlackChat Vancouver, states that we are demanding more from institutions than such statements. She says:

In the arts, as this unlearning racism moment happens for so many white people, I’m also seeing in many places that people are really digging into white supremacy and tearing down images of colonialism. And once the statues start going, the arts institutions can’t be far behind. As those things come down, I think the bricks-and-mortar institutions are going to have no choice but to address what’s in their archives, what’s actually hanging on their walls, whom they’re actually collecting.”

Further, we need to address who is making the decisions in these places, who is holding the power and how such power is being shared. There are few Black people in positions of decision-making power in most institutions across this northern part of Turtle Island and Inuit Nunangat. Those of us who have occupied positions in the art world have experienced erasure, hostility and outright violence while simply trying to do our work.

There is a perception that all are accepted, that weirdness is encouraged, that misfits fit in, all of which completely erases how anti-Black racism materializes and is enforced.

As dancer, choreographer and Black Lives Matter Toronto co-founder Rodney Diverlus has stated, “I wonder how many Black employees are reading their workplace’s Black Lives Matter statements knowing full-well of how toxic/racist the workplace is, how little Black employees are supported/nurtured, and all the other garbage that comes with anti-Blackness.”

As I read these statements in my inbox, I feel a mix of hope and rage; hope that perhaps this is the time to finally speak about the unspeakable in the arts—anti-Blackness and rage—because it’s also just as possible that these performative activisms are attempts to placate us while maintaining the status quo. I think about Chaédria LaBouvier, the first Black curator and first Black woman to curate an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, who was consistently passed over and had to fight to have her work credited because of systemic anti-Blackness. In response to the Guggenheim blacking out their social-media profile photo with a black square for Blackout Tuesday, LaBouvier famously tweeted, “Get the entire fuck out of here. I am Chaédria LaBouvier, the first Black curator in your 80 year history & you refused to acknowledge that while also allowing Nancy Spector to host a panel about my work w/o inviting me…Erase this shit.” We are indeed in a new era; “We are not having it,” as !Kona states.

For all of my Black colleagues in the arts, I hope that changes are coming, and soon. But I also know that we are being asked incredible things right now by institutions who have done little to support us in the past. !Kona states:

I’m hearing from different Black friends of mine in the arts, that arts organizations are contacting Black people to write their statements for them. Because then they don’t have to take responsibility. They don’t have to worry about coming correct. And if things go sideways, they just point to the Black person.”

How does this process reflect any sense of accountability or responsibility to Black communities? In the end we will always be the last hired, and when the statement blows up, the first fired.

Black Power and the Art Community

In Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, Susan Cahan writes about how art museums have historically exhibited a pattern when it comes to showing/writing about Black artists’ work—they ignore it largely except during times of civil unrest and uprising. She chronicles the last 50 years of the museum and gallery field in the US and clearly delineates a pattern of these institutions only showing interest when fashion dictates, or when they are required to seem “woke.” Further, she illustrates how, when galleries do show the work of Black artists, it’s often in kitchen galleries or as temporary shows, and never as part of the permanent collection of the gallery. Kosisochukwu Nnebe, a Black curator and artist based in Ottawa, explains how this phenomena also translates to an overwhelming busyness during Black History Month, the one time a year when Black artists are suddenly in demand. “In Montreal, there was this feeling of being very tokenized and being invited into spaces only when it was a particular month, February,” she says, “Sometimes the people who were inviting me to show work were Black folks who were only able to access resources for exhibitions at that time. That’s when TD is all up and open to funding these Black History Month projects and spaces are okay with handing over their space to exhibit Black artists. It also has material impacts on when/under what conditions curators and Black cultural workers are afforded resources.”

The legacy of anti-Blackness in the arts, galleries and museum sector remains. No email message with a trending hashtag will erase centuries of anti-Blackness.

I think so much about how, as Black workers in the arts, we’re often put in the position of keeping the institution secrets. By that I mean we must keep secret the anti-Blackness that manifests within the actual working of the organization. The racist things said in meetings, the terrible anti-Black exhibition titles (just how many times can you name something “The Dark such-and-such” to mean bad, evil, etc.? Please get over this), the times we are outright told we don’t belong in the field because we are Black. We are expected to flag any majorly offensive practices the institution is undertaking to help it save face, while keeping to ourselves the horror of what they would have otherwise done. Why? We are pressured to do so in order to keep our jobs, or we’re placated by a conversation with the person in HR who talks about more training. And then somehow it’s unwritten that we are not ever supposed to talk about it again. Thanks to the secret-keeping, there is this perception that the arts are liberal, open places where everyone gets to be a free spirit, everyone can be whomever they want to be. There is a perception that all are accepted, that weirdness is encouraged, that misfits fit in, all of which completely erases how anti-Black racism materializes and is enforced.

I spoke to colleagues in the arts who took the risk of speaking out, and for this, I thank them. I think of Eunice Bélidor’s project exploring how arts institutions should be working with BIPOC artists and staff, and how useful it would be if these practices were followed through.

Strategic Inequities and Replicating White Supremacy

I remember arguing in 2004 with a head of security for an hour about why it was anti-Black to introduce a policy at the gallery to bring in uniformed police officers when the DJs were planning on spinning “hip hop.” “Hip hop” is, of course, like the term “urban”: code for Black. Similarly, I remember with joy witnessing the planning for the art of hip-hop showcase H.Y.P.E: Helping Young People Excel at the Art Gallery of Ontario—led by Toronto-based art collective them.ca—in the early 2000s. I lived near the gallery and was excited to see this initiative by my local gallery. This joy and excitement was short-lived. I had my heart broken later watching them install metal detectors at the front doors of the AGO for that show. Why the metal detectors suddenly? To “keep out guns” I was later informed by the same head of security pushing for uniformed officers at youth (of colour) events.

The legacy of anti-Blackness in the arts, galleries and museum sector remains. No email message with a trending hashtag will erase centuries of anti-Blackness.

Black artists are under-supported and underrepresented by galleries.And they face uphill battles having their work engaged with critically, for many of the art critics and editors replicate anti-Blackness in their writing, including who and what they cover. Black curators have their work passed over again and again in favour of their white male colleagues at institutions across the country. I spoke with Michelle Jacques, chief curator at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. She describes a time when she was working at the AGO, where she spent the bulk of her career:

They wouldn’t acknowledge the issues as anti-Black. They would say the reason I didn’t get to do things was because I was a junior curator and hadn’t earned the right to do them. But my path though the curatorial department was so arduous. I was a curatorial assistant for five years. I had a colleague who did all of the AGO’s Indigenous programming from the position of curatorial assistant. There was no Indigenous curator position, but they wouldn’t acknowledge his leadership in his title. Yet a white man was brought in as assistant curator; he had a costly American degree that impressed them. In my final two years, I was the acting curator of Canadian art. When Gerald McMaster, whom I was replacing, decided not to return, I was told they would be posting the position. I asked if they would consider my application. They said no. I had been doing the job so well that I already had the offer from [the Art Gallery of Greater] Victoria. I resigned the next day. The AGO position went to a white man.

This experience of having to work twice as hard through piles of resistance to be able to do what a white supremacist society freely gives away to white people; the privilege for curators to get to “just do their job”; the privilege for museum professionals to be able to advance in their careers; the privilege for artists to have their work shown, critiqued and collected—these all point to the ways a white supremacist system opens doors for some while shutting out marginalized voices. !Kona recounts an experience on an arts festival jury: “[So] many large-scale events organized by white people did not have to go through the process. Meanwhile, Black, Indigenous and other people of colour were held to a really high bar in terms of the content of their applications and the process they had to go through to even get an invite. I remember one year there were two Burmese organizations that came through for funding, and the team of white people literally said they should work together because there’s two of them. Meanwhile, they funded like four Shakespeare productions.” Two or more BIPOC artists in one festival or show seems too much for some organizations to handle.

So what do Black artists and arts professionals want to see? Change—rapid, structural change.

What about the HR departments and hiring committees in the arts that keep replicating all-white institutions? Jacques states, “I think about a conversation I had with the head of human resources about how it was ridiculous that we were introducing guiding principles for programming—one of them was diversity—but there was no guiding principle of diversity when it came to hiring practices. She just cut me off and told me that I was taking the conversation dangerously close to talking about quotas.” White supremacy is reproduced in hiring practices and across HR policies. I think of the incredible work that Fractured Atlas (https://www.fracturedatlas.org/) is doing in strategic HR and tackling white supremacy in their field, and I wish more arts institutions would follow their model. For example, they have an active group/caucus practice that allows them to tackle white supremacy collectively in ways that are necessarily unequal, with responsibility for addressing whiteness falling to white folks. In this way they strive to reduce trauma and harm for their BIPOC employees. In contrast to this expansive and impressive anti-racist model of, Jacques describes an art gallery HR department that used classic white-supremacist tactics to supress Black engagement: “You couldn’t even offer to mentor somebody if they weren’t attached to a formal post-secondary program…you would try and have a conversation about how these rules just perpetuated inequities, and that graduate school was a) an opportunity that not everyone could afford and b) not the only path to curatorial work. They didn’t even want to listen to the argument.”

This strategic inequity is replicated in most docent programs, with few BIPOC folks in these roles alongside programming content that often shies away from the political. One day, at a gallery in which I worked, I was moving offices and carrying my plant to my new desk. I was quickly stopped by a white docent who confronted me and asked if the plant was marijuana. This was about a decade and a half before legalization. She asked this in all seriousness. When I discussed it with my colleagues later, I was largely unsupported, and the docent was excused because of her age, as if she had some sort of legitimate reason for her anti-Blackness. This response from my colleagues was also ageist (for what of the raging grannies, and of my 93-year-old white nana who is absolutely down with ending white supremacy and fights for it every day?). Responding in this way, my colleagues were complicit in this docent’s anti-Black racism. Their silence communicates so much—they upheld white supremacy in that moment. Until the day I left that job, this story was described by these colleagues as a “funny incident.”

When I sat down to write this piece, there were so many stories to sift through. Everyone I spoke to had countless examples of anti-Black violence on the job and in the arts. It was hard to cut these down to fit into the length of this article. The stories are endless and abundant. What does that mean? It means we need change. NOW.

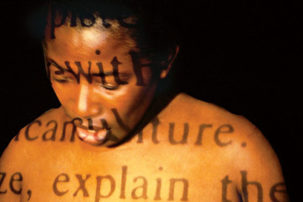

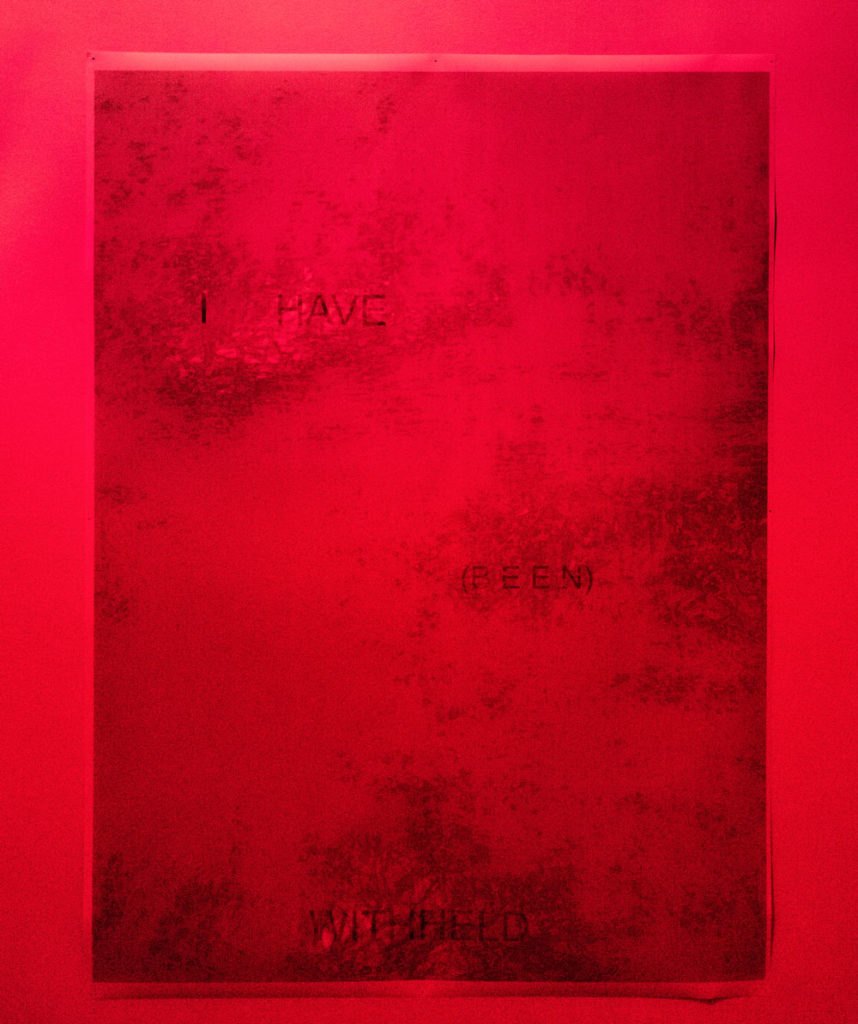

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, I want you to know that I am hiding something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable, 2019. Installation at AXENEO7.

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, I want you to know that I am hiding something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable, 2019. Installation at AXENEO7.

A Change Is Gonna Come

So what do Black artists and arts professionals want to see? Change—rapid, structural change. The activism we are witnessing in the streets, from our beds and from our homes is part of a groundswell of activism calling for change. !Kona says, “The longer people march in the street, the more change that happens. When these galleries open up, when these companies start putting their works on stage, people are going to be so much more racially vigilant and aware. They will have no choice because people will not have it.”

Galleries, museums, artist-run centres: consider giving over your space to Black artists, curators and programmers. But not as one-offs or as special events to tick off boxes. Do this in long-term ways, ways that touch change, ways that shift the existing structures in the arts. Shift the power dynamics on your boards and add the work of Black artists to your collections, especially the work of Black artists living and working here, in northern Turtle Island and Inuit Nunangat /Canada. Hire Black leaders. This country is full of brilliant creative Black leaders. Hire them. To white and POC artists: consider asking about Black representation in the exhibitions and showcases in which you participate. Ask questions about anti-Blackness and push for the support of Black artists and curators in your community. Refuse to work with white supremacist organizations. Check the receipts and don’t work with places that aren’t actively working against anti-Black racism, hiring and deferring to Black artists and leaders, and paying them accordingly.

We are witnessing an amazing revolution in our collective consciousness. The ground is shifting beneath us every minute. Change is our new constant and these are revolutionary times. It’s time to stop keeping our secrets about anti-Black racism and start demanding justice for Black people in the arts. We need to expose the white supremacy inherent to the structures of our organizations and radically reimagine what our work could look like going forward. We are creative, brave people, and we can do this work, this crucial work, together, right now. Black artists and arts matter.

We are in the moment of revolution, a revolutionary moment that has spanned decades. We can each make choices now that can dramatically address this crisis in the arts. It’s time to move beyond performative allyship. This is the time to get involved in meaningful ways that lead to structural change. This is the time to commit to rooting out and addressing white supremacy and anti-Blackness in all its forms, each and every time it rears its ugly head. It is time for a new creative future—one that we can build together.

Which side of history do you want to be on?

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, I want you to know that I am hiding something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable, 2019. Installation at AXENEO7.

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, I want you to know that I am hiding something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable, 2019. Installation at AXENEO7.