The Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, has an extensive collection of painter Edward Mitchell Bannister’s work, mostly oil paintings depicting pastoral life. Although Bannister was born in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, he is largely recognized in the United States, where he lived much of his adult life, as a pioneer of Black American art. His painting Under The Oaks, now lost, earned him a major American art prize at the Centennial Exposition, held in Philadelphia in 1876. But he’s been all but omitted from Canadian art history.

“I’ve been promoting Bannister since the 1980s because I became aware that he was a Maritime-born Canadian artist whom very few people knew about,” says artist and curator David Woods.

Woods was 15 when he learned of Bannister by chance. Woods’s family emigrated from Trinidad to Canada in 1972, settling in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. He remembers listening to WUNR, a radio station that came through the airwaves from Boston late at night—his only regular opportunity to hear Black music on the radio. One night they did a Black History Month segment on Bannister, which introduced Woods to the artist and his work.

As Woods got older, his fixation with Bannister continued, but he was confounded by the fact that few others seemed interested in the artist’s historical importance. “The white art establishment knew nothing about him. And sadly, the Black folks didn’t know much about him either. So, I was kind of a lone ranger in that field.”

Woods, who in addition to being a curator is also a visual artist, poet, playwright, theatre director and cultural organizer, has devoted his career to artists and stories like this. He’s perhaps most known for co-curating the 1998 exhibition “In This Place: Black Art in Nova Scotia” at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design’s Anna Leonowens Gallery. It was a vital survey of art, dating as far back as 1886, from both urban and rural Black communities throughout Nova Scotia. By uncovering the histories of many Black Maritime artists, Woods created a sense of place, a way to teach emerging artists about the work of those who preceded them, whose legacies had largely gone undocumented and unpreserved.

This penchant for teaching makes sense: Woods’s foray into art started in education. In 1981, after three years studying political science at Dalhousie University, he was offered a job running cultural youth programs with the Black United Front, a Nova Scotian Black advocacy organization founded in the mid-1960s. He agreed to do it for a year, thinking he would then go back to Dalhousie for law school. He never did. “I’d never had the opportunity to artistically express myself growing up in a family where the immigrant demand for lawyers and doctors was the preeminent thing. You couldn’t have aspirations outside of the conventional,” he recalls. “I moved out and soon discovered that my other ambitions had taken over. I was always involved in the arts—writing and painting and all those things—but I never elevated it as central.”

The program was intended to teach Black children adopted into white families about their cultural heritage. Woods insisted the eligibility criteria be broadened to include any Black students who wanted to participate. “I basically said, ‘I don’t think anybody’s being taught their culture properly. These kinds of superficial things, where you have a workshop here and there sporadically, don’t work.’ If I was going to do anything, I wanted it attached to the school system.”

Black students from all over Halifax and Dartmouth flocked to the program, which taught cultural identity through poetry, plays, painting, history lessons and quizzes. The program ended after the first year. But the students refused to let it go, and they started their own organization, the Cultural Awareness Youth Group (CAYG). Woods led the organization and curriculum until 1989.

Pamela Edmonds, who is now senior curator at the McMaster Museum of Art in Hamilton, was a member of the CAYG while she attended Prince Andrew High School in Dartmouth. She says she was one of few Black students at her school, which made the CAYG a kind of haven: “It created a sense of community around artistically inclined Black students. It gave me an inkling that this was actually something I could work towards, being an artist or being in an artistic field. [Woods] was really a mentor to a lot of artists, then and beyond.”

The students wrote and acted in their own plays, created artwork and participated in inter-school quiz competitions. Edmonds refers to the experience as “knowledge-building about Black identity.” One of these plays is the subject of Sylvia D. Hamilton’s 1992 documentary Speak It! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia, which focuses on a group of students as they explore their Blackness through the CAYG and perform in Woods’s production Black Journey. Like Woods’s work, Hamilton’s arsenal of acclaimed documentaries and writing, centred on place-making and reclamation, is a crucial document of Nova Scotian history and artistic practice.

David Woods performing with Voices Black Theatre Ensemble at Halifax Public Libraries Black History Month event in 1998. Courtesy Cultural Awareness Youth Group Archive.

David Woods performing with Voices Black Theatre Ensemble at Halifax Public Libraries Black History Month event in 1998. Courtesy Cultural Awareness Youth Group Archive.

Woods became versed in Black Nova Scotian history because he felt an obligation to teach more than just the few regurgitated facts about Black Loyalists that students usually learned during Black History Month. His first curatorial project was a photography exhibition on the Black history of Halifax’s North End neighbourhood. Following the launch of Voices Black Theatre Ensemble, in 1990—where he honed his playwriting skills and wrote radio dramas for the CBC—Woods also helped found the Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia in the early 1990s, getting deeper into cultural organizing and advocacy.

Around the same time that Woods’s projects began to probe the province’s histories, events in the region highlighted the urgency of his work. The social landscape of Halifax had been rocked by the 1989 Cole Harbour District High School brawls, which brought the racial tensions between the city’s white and Black communities to a head. A violent fight broke out at the school in January 1989 between students from the predominantly white Eastern Passage and Cow Bay regions, and the predominantly Black regions of North Preston, East Preston and Cherry Brook. A CBC article reporting the incident details someone getting “smashed in the face” and having “their face split open.” In another CBC article published 30 years later, Corey Beals, who was a student at Cole Harbour at the time, described how the fight led to the province reconsidering its response to anti-Black racism and the experiences of Black students, who felt underrepresented. Woods was part of a race-relations committee created by the local school board, one of many such committees that emerged in the wake of the violence.

In 1992, an exhibition at the Dalhousie Art Gallery featuring six works from Black American artist Carrie Mae Weems’s Ain’t Jokin’ series (1987–88) revealed the chasm between Halifax’s Black community and the art establishment. Weems’s attempts to force audiences to confront their own racism—through the satirical use of racist jokes and tropes about Black people, such as equating them to apes—were interpreted by members of Halifax’s Black community as insensitive. Black students at Dalhousie staged a sit-in at the gallery, demanding the works be removed. “There was not a good relationship between the arts community and the Black community [at that time],” says Edmonds. Representation of Black art had been historically lacking in the area’s institutions, so a display of works that illustrated harmful stereotypes, even while critiquing those same stereotypes, left a sore feeling.

“In This Place,” co-curated with Harold Pearse, was initially going to show work from current and former Black NSCAD students, but the first call for submissions received few responses. When Woods was brought on as a co-curator, he wanted to see if he could widen the exhibition’s scope. “There was no route to search for art,” he remembers, “because there had been no art shows in the institutional sense.” Curating would have to be done very differently: “Black artists did not exhibit in galleries, so you couldn’t just phone up galleries and make a request. I knew people in every Black community, so I just got in a car and drove. A month later, I showed up with 300 photographed pieces of art. And that’s when we realized we had something.”

“In This Place” opened on February 16, 1998, and included more than 100 works from 46 artists, many of which had never been exhibited before. Paintings, ceramics, handmade prints, quilts, wood carvings, woven baskets and collages—it was a true myriad of mediums. The exhibition included work by student, self-taught and professional artists: Justin Augustine’s paintings; Jim Shirley’s monotypes; Ruth Johnson’s handprinted greeting cards; contributions from mixed-media artist Crystal Clements; and work by craft artist Audrey Dear Hesson, the first Black graduate of NSCAD. Woods’s poem Abode (1996), from which the exhibition gets its title, was mounted on Plexiglas in the centre of the gallery. He used the poem as a guide to tie the multidisciplinary works together, since he started looking for work before any curatorial aim was determined. Its last stanza speaks to the agency Black artists have over their own narratives:

So that here in this place—

Even amidst oppression,

When both they and I look—

My soul will still be housed in an abode of beauty,

And its riches will still be mine.

Woods emphasizes that “In This Place” presented work that Black people knew had been happening; it was largely the white art world that was unaware of its history. In a way, Woods worked like an archivist, documenting these pieces before they could be lost to memory. Meril Rasmussen’s 1998 thesis essay is a thorough firsthand account of the history of the exhibition, an essential source unveiling the impact of “In This Place.” In it, Rasmussen writes that “Powerful legacies, both individual and collective, were unveiled, forever changing the expectations of Black artists in this province.”

Edward Mitchell Bannister, River Scene, 1885. Oil on canvas, 20.3 x 35.3 cm. Collection Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Edward Mitchell Bannister, River Scene, 1885. Oil on canvas, 20.3 x 35.3 cm. Collection Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

The exhibition toured Nova Scotia, starting in Halifax and then travelling to Shelburne, Sydney and New Glasgow. It received mostly positive reviews, but not everyone lauded the collection. Award-winning poet George Elliott Clarke, who grew up in Halifax and became a critical voice in literature chronicling the lives of Black Nova Scotians, reviewed the show for Mix, a now-defunct national art magazine. “Given the random fashion in which this treasure trove has been assembled,” he wrote, “it lacks any sense of period or even geographic consistency.”

Still, it was an opportunity for engagement and honest discourse about Black Nova Scotian art in the public sphere. “Weymouth Falls is [an example of] a particularly talented community, but nobody ever showed their art anywhere. If you’re doing wood carving in the back of Weymouth Falls, you don’t consider [your work] the art that goes into galleries. It’s not from any deficiency of anything. If nobody has ever approached you and treated your work as art, you don’t automatically get this idea that it should be shown in galleries,” says Woods.

“In This Place” came during “a little renaissance of Black exhibitions” in the 1990s, recalls Edmonds, who organized a few exhibitions with Sister Visions, a collective of Black women artists, in the years following. This renaissance was marked by artists such as Buseje Bailey, who was in residence at the Centre for Art Tapes and exhibited frequently in Nova Scotia, and work by Harold Cromwell, Ralph Cromwell and Ada Cromwell on display at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and MSVU Art Gallery. It seemed like an opportune time.

In 2006 Woods was hired by Art Gallery of Nova Scotia director Jeffrey Spalding to be associate curator of African Canadian art there. He curated two exhibitions (“Visions in African Nova Scotian Art” and “The Soul Speaks”), started developing a permanent collection of African Canadian art (even acquiring a Bannister painting for the collection) and fundraised for more exhibitions. It was a short-lived stint; Woods was let go just a few weeks after Spalding left the gallery, in 2007.

According to Woods, he was working on creating structural change from within the institution, but his brief time there allowed for little progress: “There’s a difference between structured commitments versus tokenism. Tokenism is easy. You just hire a person for a brief period of time or you book a show and then brag about it for the next 20 years.” Since then Woods has mostly worked independently. He’s tenacious and uninterested in depending on the whims of institutions. “After the AGNS, I learned, ‘Brother, if they could look at all that wealth [of Black creativity] and still treat it like that,’” he says, “I ain’t going to burn myself out for other folk. I believe in what I can do but I also don’t believe I can be some kind of messiah figure.”

Woods is in the early stages of writing a book exploring the history of Black art in Nova Scotia. He’s hoping it will spawn other work and research into Black art histories across the country. Other than the recent Towards an African Canadian Art History (2018), a collection of essays edited by Charmaine A. Nelson, there is little in the way of a comprehensive literature. The absence makes the risk of ahistoricism more immediate: contemporary academics and curators have few places to look.

Woods’s concern is that there are also so few people who can speak to these histories. “The kids don’t stay in these communities. The old people get old. The churches rot. I’m not elevating these stories as anything more than what they are. It’s just that I understand these places. I travel these places. I talk to these people. And it would be great to just represent their stories before they completely expire.”

In early 2022, an expanded version of an exhibition of quilts Woods curated (and contributed work to) in 2012, “The Secret Codes,” will be going on a national tour, starting at the Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown. The quilts capture community history and are a distinguished vehicle for storytelling. The exhibition title refers to how quilts were used to guide enslaved peoples fleeing to freedom via the Underground Railroad. There has yet to be a major exhibition of Edward Mitchell Bannister’s work in Canada, but Woods is working toward borrowing paintings from the Smithsonian to finally give the artist the star treatment in his home province. Slated for early 2023 at the Owens Art Gallery at Mount Allison University, Bannister’s homecoming will happen more than 50 years after Woods’s fateful late-night radio discovery. National recognition is a long time coming for them both.

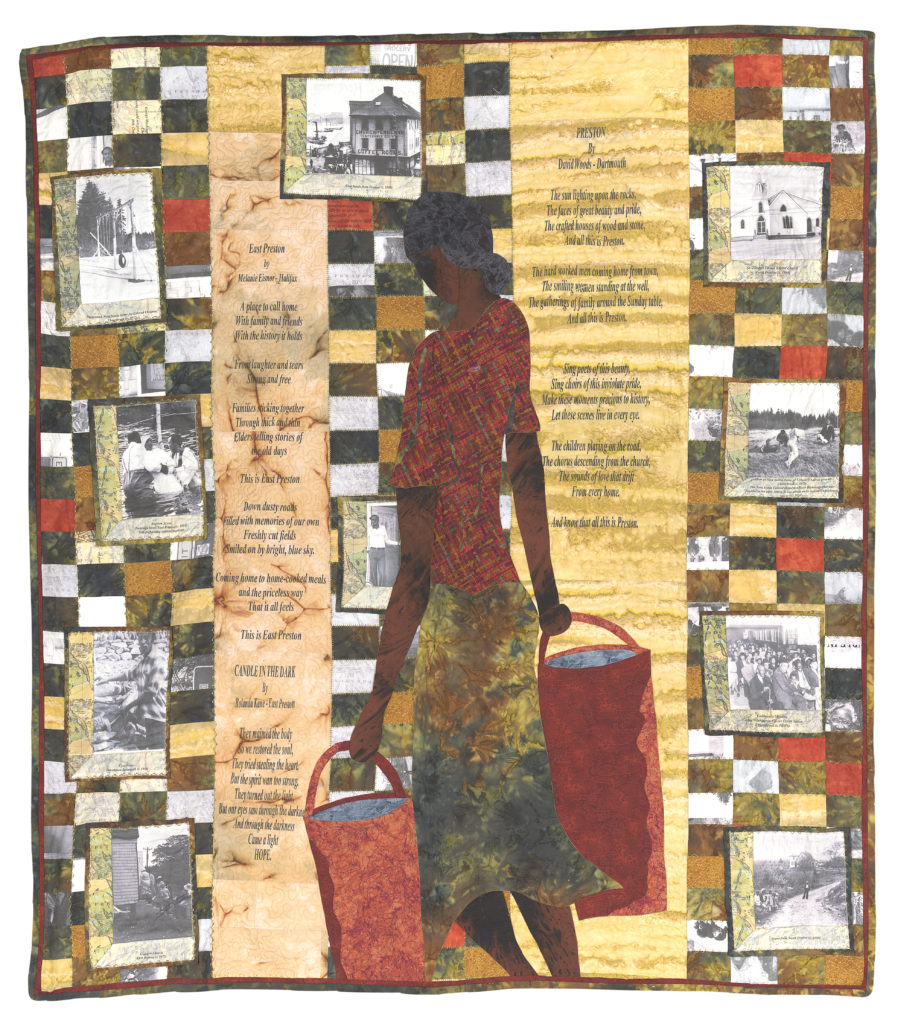

Preston, 2007. Designed by David Woods. Quilted by Laurel Francis. Pieced, appliquéd, machine- and hand-stitched, hand-dyed quilt with photo transfers, 1.47 x 1.32 m. Images on quilt courtesy the Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia.

Preston, 2007. Designed by David Woods. Quilted by Laurel Francis. Pieced, appliquéd, machine- and hand-stitched, hand-dyed quilt with photo transfers, 1.47 x 1.32 m. Images on quilt courtesy the Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia.