Laura Anzola

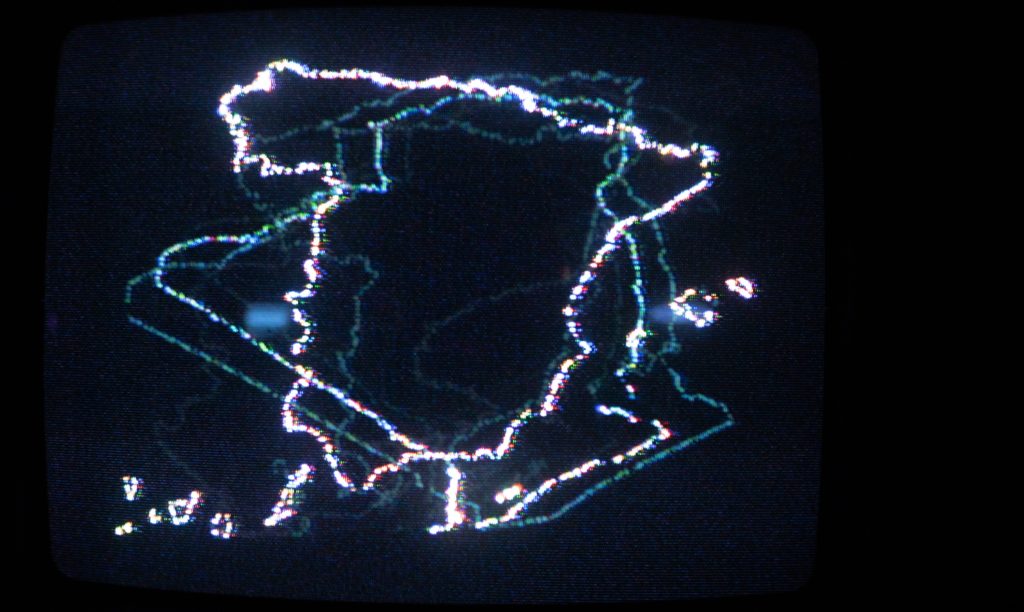

Animation and new media artist Laura Anzola has moved around a lot: born and raised in Colombia, Anzola relocated to Germany for her MFA before settling in Calgary two years ago. “Moving had a big impact on me, and started this process of me getting deeper into understanding borders, not just geopolitical borders but also invisible borders that have to do with emotions, cultures, languages and belonging.” Anzola’s installation Borders v.02 (2019) uses cathode-ray-tube (CRT) televisions and electrical signals to metaphorize the erosion of borders. Her decision to work with TVs calls attention to the ways televised media shapes popular understandings, and misunderstandings, of borders. During her studies in Germany, Anzola learned from artist Darsha Hewitt about how to hack a tube TV to function as an oscilloscope, transforming the TV’s electrical signals into horizontal and vertical lines. Using a 555 timer chip, and later a modular synthesizer, Anzola was able to create and control glitches in these lines, a process that allowed her to “imagine borders as something more malleable and movable and permeable.” The artist carefully compiled these glitches and arranged them in a continuous composition across eight CRT TVs, which take the viewer through moments of anticipation, frustration and adaptation. At the end of the score, the lines morph into maps outlining countries that require Colombians to have a visa to enter. The TVs are arranged in a circle, reflecting Anzola’s interest in loops and cycles. “Every time I move from one place to another, I have to restart the process of adapting to culture, people, spaces and language. Home, for me, is moving,” she says.

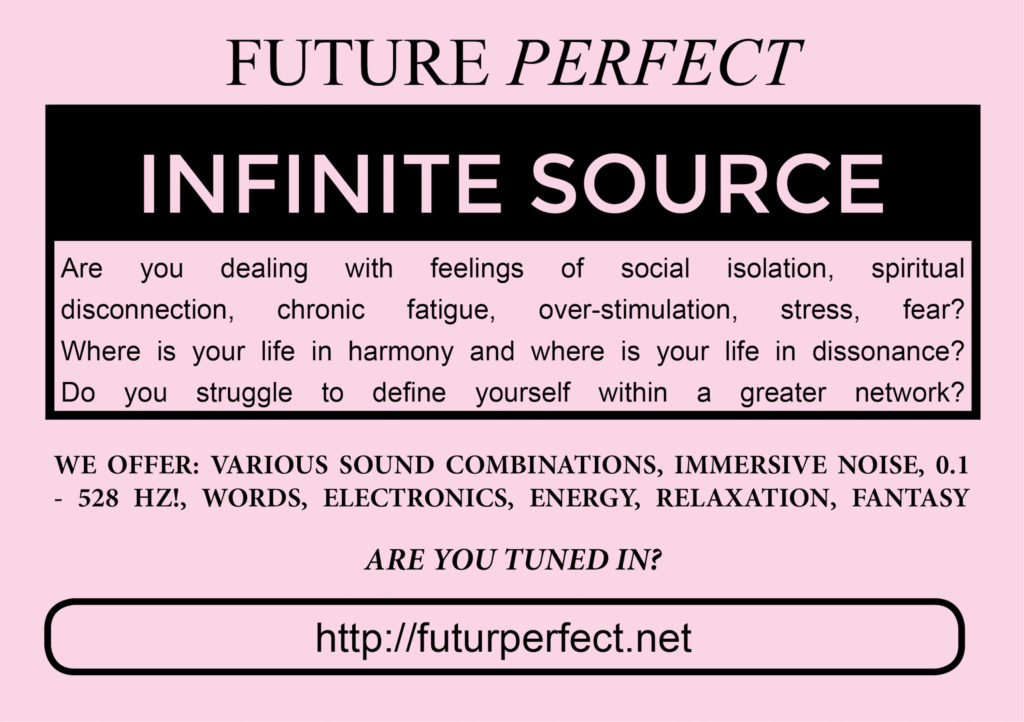

Jawa El Khash, Hammam (still), 2020. VR and WebGL simulation, 10 min.

Jawa El Khash, Hammam (still), 2020. VR and WebGL simulation, 10 min.

Jawa El Khash

“Light represents the connector between the sublime and the human, between the visible and the invisible,” says Toronto artist Jawa El Khash. Across many forms of artmaking—including virtual reality and holography—El Khash harnesses light as a medium. Light is central to her most recent VR work, Hammam (2020), a virtual bathhouse emulating those the artist remembers fondly in Syria. “Damascus, the city I grew up in, is very chaotic,” she explains. “When I used to visit these bathhouses, they were like a VR experience because they separated you from the outside world and enticed all of your senses.” El Khash wants viewers of the work to be fully immersed, whether they are using a VR headset or the work’s more accessible WebGL simulation. In Hammam, intricate Islamic architectural details, artificial sunlight and 360-degree audio make this virtual bathhouse feel real. “VR uses light rays to create the illusion of reality,” she says. “I’ve always been interested in how we can use technology to reveal things to ourselves that we don’t see.” El Khash also creates holograms using light, lasers and optical equipment to produce illusory 3D vignettes. Her favourite subject for these holograms is butterflies— the “universal symbols for life, death, resurrection and metamorphosis.” She is also interested in the short lifespans of butterflies, and how they spend their lives in constant motion: “I think of butterflies as nature’s immigrants. They are migratory creatures who move around just like we do.” Recurring butterflies in Hammam and her other VR works such as The Upper Side of the Sky (2019) add a “soulful presence” to these digital environments.

Clockwise from top left: Fallon Simard, Lost In The Sauce, 2019; Top Surgery 2, 2019; Land Back, 2020; Pronouns Are Mandatory, 2019. Memes.

Clockwise from top left: Fallon Simard, Lost In The Sauce, 2019; Top Surgery 2, 2019; Land Back, 2020; Pronouns Are Mandatory, 2019. Memes.

Fallon Simard

Video, film and meme maker Fallon Simard sees social media as a space to connect with and advocate for queer, trans and Indigenous communities. In his previous work at the Native Youth Sexual Health Network (a grassroots organization that teaches Indigenous youth across the US and Canada about sexual and reproductive health), Simard “used memes as a tool to make educational content around mental health and different queer and gender identities.” Simard carries this work into his artistic practice, creating memes to address topics important to him and his Treaty 3 Anishinaabe community. In his 2017 OCAD University thesis exhibition, “Bodies That Monetize,” Simard used memes “to look at mental health and colonialism—how a disconnection from land and community and time and space creates bad mental health afflictions for people.” He explains that much of that work considered “abandonment, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. Through those memes, I really tried to make accessible a sort of language around how those things look and feel and share them with people.” Though his memes are sometimes presented in galleries, Simard feels they are best experienced virtually, on Instagram: “I love the quick connection that I can make with friends and the shared exchange of laughter.” A curious creator interested in many facets of artistic production, Simard has also begun to work with more tangible objects with the recent opening of his online store, Contrary Company. The store features face masks and kookum scarves designed with bold colours and patterns drawn from traditional and contemporary Anishinaabe concepts. Online and IRL, amid and in spite of colonial grief, Simard’s creations find joy, humour and connection in queerness and Indigeneity.

David Bobier, Transcommunicator I & II (detail), 2019–20. Found objects, programmable music boxes, paper scrolls, LED lights, tripods, wireless audio system, tactile transducers, wood and steel brackets, dimensions variable. Photo: Julia Salles.

David Bobier, Transcommunicator I & II (detail), 2019–20. Found objects, programmable music boxes, paper scrolls, LED lights, tripods, wireless audio system, tactile transducers, wood and steel brackets, dimensions variable. Photo: Julia Salles.

David Bobier

David Bobier is an artist and the founder of VibraFusionLab, a media arts centre in London, Ontario, dedicated to supporting multisensory and inclusive arts practices for Deaf, blind, disabled and hearing artists and audiences. Bobier and his lab focus largely on vibrotactile arts, a practice that uses transducers, devices that are “similar to the core of a speaker, but they’ve been modified to enhance the vibration of the frequency of the sound.” As Bobier explains, “All frequency that is within a lower frequency range can be experienced as tactile.” The artist started working with vibration in the 1990s, when he adopted two Deaf children. “I did a lot of studio work in that period exploring the disparity between hearing culture and Deaf culture.” By using vibration as both a medium and a language, Bobier creates interactive and wearable artworks that can enliven our sense of touch. He often works with other artists to add vibrotactile elements to their projects as well: “I’m big into collaboration and developing partnerships. And those partnerships tend to create networks.” Bobier sees growing support around the multisensory arts in galleries and museums today, though he feels we are still in the early days of this alternative practice. He is hopeful about what this means for Deaf and disabled artists who have historically been marginalized by art institutions. “In my own work and at VibraFusionLab, I always look at who is in the audience and who isn’t. The ones who aren’t in the audience are the ones whom we need to be talking to—giving them authority on what happens next and having them direct us on where we need to go.”

Lauren Marsden, The Coconut Effect (still), 2020. Digital film and sound, 8 min.

Lauren Marsden, The Coconut Effect (still), 2020. Digital film and sound, 8 min.

Lauren Marsden

As a filmmaker and media artist, Lauren Marsden has always had a peripheral interest in sound. Recently, the Vancouver artist delved into the worlds of ASMR and Foley in her video work The Coconut Effect (2020). ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) describes the pleasant tingling sensation in the scalp and neck that some people experience as a result of audio and visual triggers, while Foley is the practice of creating in-studio sound effects for film and television to emphasize certain qualities of a scene. The title of Marsden’s work refers to the early Foley practice of clacking together two coconut halves to simulate the sound of galloping horses. Marsden wanted to use ASMR and Foley to evoke the feelings and sounds she associates with her ancestral place of origin, Trinidad, during a pandemic lockdown that prohibits her from visiting this place and her family. Marsden often uses her work as a space to access her Caribbean roots; in developing The Coconut Effect, she wondered how she could use food to gain cultural knowledge. “I started with what I could get in a short amount of time,” she says. “I would play around with tamarind or okra to see what sounds these foods would make. So I let the food tell me the story.” The story, unfolding in subtitles laid over video of Marsden manipulating these foods with her hands, describes a loose and dreamlike voyage overseas. It follows “a journey of this person who starts off in a Caribbean environment and then ends up in a northern, colder climate, which has been somewhat my experience— as someone who is from there ancestrally, though I’ve always lived in Canada,” Marsden says. “I wanted to play on the idea of emotionally being in two places at once.”

Marissa Sean Cruz, XP (still), 2020. Single-channel HD-video projection, 6 min 34 sec.

Marissa Sean Cruz, XP (still), 2020. Single-channel HD-video projection, 6 min 34 sec.

Marissa Sean Cruz

Halifax artist Marissa Sean Cruz looks to the pop-cultural icons and artifacts of the mid-2000s with nostalgia and criticality. Pulling together songs and characters of the recent past, Cruz allows pop culture and fine art to share space in her video works. Different cultural touchpoints allow audiences to connect with and gain insight into her work through existing familiarities with the likes of Demi Lovato or Coldplay. Cruz has created a cast of original characters—including an animatronic puppy; a blue-skinned, red-haired ogre; and a futuristic fighter—whom she performs in her videos. “Costuming and cosplay are super important, especially when thinking about the way the world is right now, and about speculative fiction and generative action—being able to access fantasy [to] imagine betterment but also embrace joy and laugh,” says Cruz. She also uses satire to uncover institutional oppression and exploitative labour practices. In The smoke-filled room (2018), Cruz dresses up and performs as the Jollibee mascot to critique American imperialism and the exploitation of Filipino migrant workers. “It’s an important way to dismantle these systems without burning out,” she explains. Cruz regards the mid-2000s with both fondness and skepticism, valuing the cultural output of the time when she came of age while also confronting the pervasive colonial violence and racism of the past and present.

Future Perfect, Infinite Source, 2020. Flyer, 10.1 x 15.2 cm.

Julia E. Dyck, Auditory Fantasy, 2020. Performance at Volksroom, Brussels, February 3, 2020.

Julia E. Dyck

“Sound has always been with me,” says Julia E. Dyck, a Winnipeg-born artist now based between Montreal and Brussels who experiments with music, composition, visual scores, performance, community radio and sound installation. Her work concerns the environment, technology, the body, consciousness—and their many interrelations. Dyck harnesses electromagnetic signals to reveal unseen and unheard natural phenomena. Inspired by the radio-astronomy work of scientist Elizabeth Alexander, who discovered frequencies emitted by the rising and setting sun that are inaudible to the human ear, Dyck and collaborator Diana Duta recorded solar frequencies for their performance work Wave Debris (2020). Dyck and Duta mathematically translated these frequencies into the audible spectrum, allowing listeners to hear the sound of the sunset. Dyck draws attention to the sounds and occurrences around us that are imperceptible, like weather radio—the long, low frequencies generated by weather patterns that resonate from distant parts of the world—or those that are often ignored, like the cacophony of city noise. In Infinite Source (2020–), Dyck and artist Amanda Harvey, under the banner Future Perfect, developed a durational sound performance that layers field recordings from urban environments in Canada and Europe, aiming to make these noises more tolerable, even enjoyable. “We were really interested in perpetual contact with the world and the polyphony of urban ecosystems…. How can we make something that can enhance this experience and make it less anxiety-inducing?” In recomposing the sounds of urban and natural environments, Dyck allows her audience to experience their surroundings “in a way that might generate pleasure or fantasy.”

Colby Richardson, Composition for PowerPoint (still), 2019. Single-channel video, 14 min.

Colby Richardson, Composition for PowerPoint (still), 2019. Single-channel video, 14 min.

Colby Richardson

Regina-born, Winnipeg-based artist Colby Richardson first became interested in media arts when he was gifted an analog-video colour corrector. He has continued collecting and experimenting with obsolete video equipment ever since. “What I like about older gear is it can only do a few things,” he explains. “The limitations are huge to me.” Richardson similarly uses the constraints of smartphones and other contemporary software to his advantage. Rather than hacking the hardware of the electronics he uses, he manipulates technologies without breaching their surfaces: “I’ve always been more interested in working with the inherent tools that are within devices.” Richardson’s screens are self-referential; TVs and phones infinitely loop video of themselves. This aesthetic choice draws on the feedback of early video, where the effects are dizzying but the process is remarkably minimalist. In developing two of his most recent works, he wondered, “How can I create a medium-specific piece about an iPhone or PowerPoint?” For Performance for Aging Apple Devices (2020), Richardson livestreamed a formalist yet humorous audiovisual composition using only iPhones, iPads and iMacs, combining layers of feedback with FaceTime. For the performance Composition for PowerPoint (2019), he explored the vast sound and animation possibilities of the presentation software’s transitions. “PowerPoint is actually a very sophisticated single-frame animation program,” he says. In this work, three PowerPoint presentations played alongside one another, with trippy slide transitions unfolding seamlessly across the expanded frame. By revealing the potential of ubiquitous tools, Richardson reimagines “technology that almost everyone in the audience would have some sort of relationship with.”

Casey Koyczan, The Balance, 2021. Wearable technology and performance, dimensions variable. Photo: Casey Koyczan.

Casey Koyczan, The Balance, 2021. Wearable technology and performance, dimensions variable. Photo: Casey Koyczan.

Casey Koyczan

Casey Koyczan is a Tlicho Dene artist originally from Yellowknife and now based in Winnipeg. Although largely known for his virtual-reality works, Koyczan also merges electronics and found natural materials to explore the interrelations between technology, environmentalism and culture. “I moved away from Yellowknife when I was about seven years old…. I’ve only been back home a few years out of that time. There’s always been a disconnect between me and my culture, and I’ve been working hard to learn my language and traditional practices.” Music is of particular importance to Koyczan, especially in his use of the Dene drum. “The drum is something that I feel connects me more to my culture than anything else,” Koyczan says. “It’s blood memory for me. It feels like I’ve been playing it for the last hundred years.” For his performance The Balance (2021), Koyczan connects his drum to a contact microphone and runs the signal through sound-editing software to trigger audio and visual cues—thunder, lightning, reverb—with each hit. As part of this immersive performance, Koyczan also wears a choker made of moosehide and caribou antler that creates delays on different frequencies of his voice, while simultaneously activating contemplative video projections of wind and snow. Currently, Koyczan is working on an interactive installation called Ełexiìto˛ ; Ehts’o˛ ò˛ / Connected ; Apart From Each Other (2021). The work will consist of five hollowed-out willow-tree logs suspended from the ceiling, with each one housing speakers connected to laser range scanners that will summon the sounds of drumming and chanting as viewers approach them. Koyczan explains, “The installation communicates my journey of learning about my culture from a distance, using technology.”

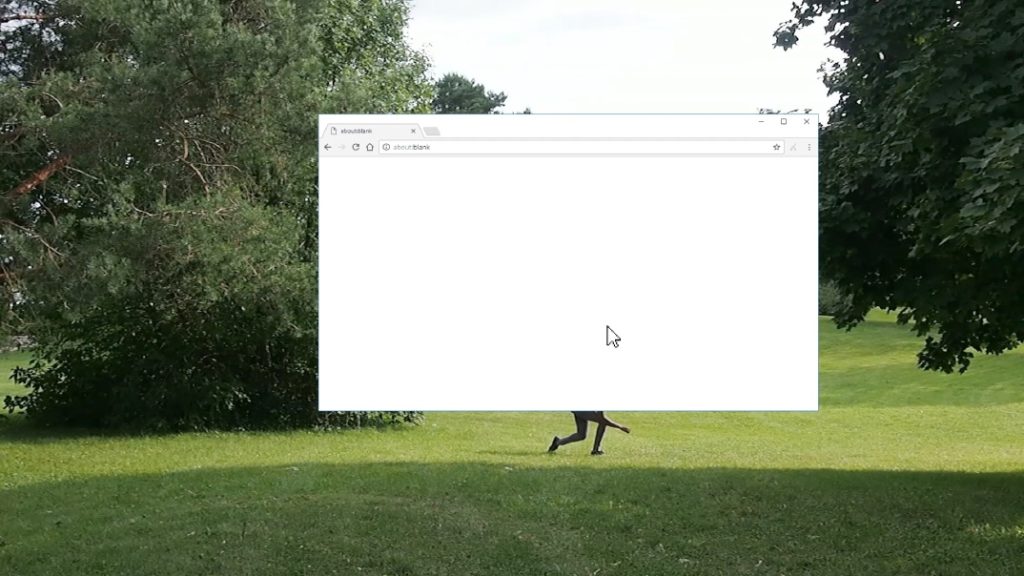

Ronnie Clarke, cursor dance, 2017. Digital performance video, 3 min 49 sec.

Ronnie Clarke, cursor dance, 2017. Digital performance video, 3 min 49 sec.

Ronnie Clarke

“I’m interested in technology as a subject and a medium,” says Toronto artist Ronnie Clarke. Her layered, multimodal practice synthesizes dance, performance art, sound art and video. “I’m really informed by movement,” Clarke says. “Even if I’m doing work in video, it readdresses the body.” In cursor dance (2017), video of an outdoor performance by the artist fills a desktop computer screen. The centre of the screen is obstructed by a browser window, over which the computer’s cursor reenacts the hidden motions of Clarke’s upper body. Linking the navigation of virtual space to the body’s gestures, cursor dance reveals the manual choreographies enacted through the use of a mouse or trackpad. Clarke has a background in classical ballet but, frustrated by the constraints of this exacting dance style, began investigating ways to digitally expand on her ideas and learned movements. She uses post- production video-editing techniques to control how her body is seen: “I’m always interested in technology and how it mediates people [and] how much of my body is rendered or represented through technology.” Her recent virtual performance SUNWALK (2020) brought remote audiences together for a participatory exercise over the video-conferencing application Jitsi, timed to coincide with the setting sun and accompanied by droning synth music. Clarke encouraged participants to “walk around their computer screen to the beat of this experimental soundtrack at sunset…. The premise was getting people moving but also feeling like they were part of a collective performance even though we don’t have the means to be in the same space right now.” During the pandemic lockdown last year, Clarke also created an interactive digital soundscape—using online audio tools and recordings captured from Toronto streetcar rides—to share the sounds that helped her find calm.

*

Laura Anzola, Borders v.02 (detail), 2020. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo: Matthew Waddell.

Laura Anzola, Borders v.02 (detail), 2020. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo: Matthew Waddell.