I first met Chen Zhen in 1995, when I was living in Paris and teaching at the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts. While there, I was introduced to a number of Chinese artists and curators who had immigrated to France, including the artists Yang Jiechang, Shen Yuan, Huang Yong Ping and Yan Pei Ming and the curator Hou Hanru. It was the latter who suggested that I contact another Chinese artist living in Paris: Chen Zhen. Hou said he was sure that we would get along, and his intuition intrigued me. Apart from our Chinese heritage, what common ground could I possibly share with someone who had grown up an ocean away? I did not know much about Chen, other than that he was one of many Chinese artists who had moved to Paris during the 1980s and had chosen to remain after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. I was interested in learning more.

At this time, I was experiencing profound artistic self-doubt, and was not even sure if I wanted to continue being an artist. I was acutely aware of the disjuncture of my experience of the world and the art world—the art world that I knew did not seem to reflect the largeness of the world. My move to Paris was an attempt to reconsider my own place in this world. What was important for me at this time was to think about how everyday life can infuse art with a relevance that reverberates far beyond the confines of the art world and its institutions. I would soon discover that Chen Zhen had long ago chosen a similar route.

In 1995, the art world was only beginning to acknowledge artists and curators working outside of Europe and North America. In spite of the prescience of conceptual art and its relationship to the processes of globalization, the Western art world has been slow in transforming rhetoric into practice. I recall meeting the curator Okwui Enwezor for the first time in Paris in 1995. He was relatively unknown then, and was interested in curating exhibitions focused on contemporary African art. But he was having difficulty finding institutions that would commit to his projects. Nevertheless, something was in the air. New faces were appearing in the art world, from places such as China, Africa, Mexico and other previously marginalized regions, and their presence contributed to art a new and urgent purpose. There was much to learn during my time in Paris.

I called Chen and was invited to his apartment in the 13th arrondissement, near Paris’s Chinatown, for dinner. I had never been to this part of the city before and was struck by how different it looked from the rest of Paris—this area was full of concrete high-rises and an ambitious modernist complex called Les Olympiades. An uncanny feeling of familiarity—a “spiritual running-away,” as Chen would say—washed over me as I walked through crowds of Chinese Parisians going about their day. At that moment, I suddenly felt as though I was on my way to meet not a stranger, but rather someone connected to my past. And in a sense I was.

My knowledge of China consisted of what I had learned from my immediate family as I grew up in Vancouver’s Chinatown. My grandfather would tell me stories about what China was like both before and after the Communist revolution of 1949. Every month he would bring home a copy of China Today, an illustrated publication glorifying life in Mao Zedong’s China. Chen Zhen could have been one of the children pictured in its pages, which I stared at as a boy. It was difficult for me to articulate, but as I walked towards Chen’s apartment, I sensed an opportunity to know myself better through another.

I arrived at Chen’s street but had difficulty locating his apartment, for no number existed on his door. (Or perhaps there was a number, but I could not find it.) It was only when Chen appeared in the courtyard of his complex that I discovered where I was going. In hindsight, the absence of a number could be said to point to a kind of dislocation of location, a home without an address. Chen has explored this sense of dislocated habitation in much of his work. Maison portable (2000) is simultaneously a cradle, a cage, a wagon, a playpen, a Chinese sedan and a prison. This work is constructed mainly out of wood, bears handles at both ends and is supported by four wheels. Its interior is filled with red candles melted into the shape of a figure lying in repose. The caravan-like form of the work suggests mobility, and the viewer is invited to speculate on the future of the figure inside.

Describing Maison portable, Chen has written, “The house can be a utopian space, virtual, immaterial, spiritual, a space ‘between.’ This is why the real house has no address. I am a ‘homeless person’ and even Paris, where I have been living for fifteen years, is just a stopover for me.” Of course, Chen did have a fixed address and was not homeless in the sense of being destitute. He did not identify himself as a nomad—a figure of great currency in today’s art world due to its embodiment of the contemporary world’s flow and dissemination of people and power. Indeed, the contemporary art world tends to ambiguously equate the artist and the nomad.

Since the emergence of identity politics in art, artists have been called upon to represent the ethnic communities of which they may be a part. The result has been the reification of essentialized ethnic identities, a model that fails to reflect the increasing degree of transnational mobility and hybrid experience that many artists working today enjoy. Chen has negotiated this contradiction by working with the idea of “homelessness” as developed by ancient Chinese philosophers such as Shen Tao and Lao-tzu. The former famously advocated that one should “abandon knowledge, discard self” in order to experience a life unencumbered by the conventions of the social status quo. Lao-tzu claimed that:

When all beneath heaven is yourself in renown

you trust yourself to all beneath heaven,

and when all beneath heaven is your self in love

you dwell throughout all beneath heaven.

This passage describes an unanchored state in which the self is located “all beneath heaven” and has the capacity to open up to the world. The Tao-te Ching (Classic of the Way of Power) (ca. 600 BCE) is attributed to Lao-tzu, who was record keeper at the royal court of the Zhou Dynasty. The Tao-te Ching is a set of paradoxical poems, metaphysical teachings emphasizing the contingency and continuity of all that comes to pass in the world. The Tao, sometimes translated as “the Principle” or “the Way,” represents unimpeded harmony. It is everywhere and in everything. It is something each and every human being must discover within. One must give oneself over to the world and to the contingencies of existence, but still lead an ethical life. Throughout his career, Chen has spoken about finding love in one’s relationship to the world, a kind of love that can only be found when one forsakes self-love. Chen’s notion of surrendering the self does not have to do with achieving transcendence, but rather with challenging us to revise our notions of identity and think of ourselves differently—to loosen the grip of individualism, with its inherent inflexibility, focus on self-affirmation and bias against collective memory.

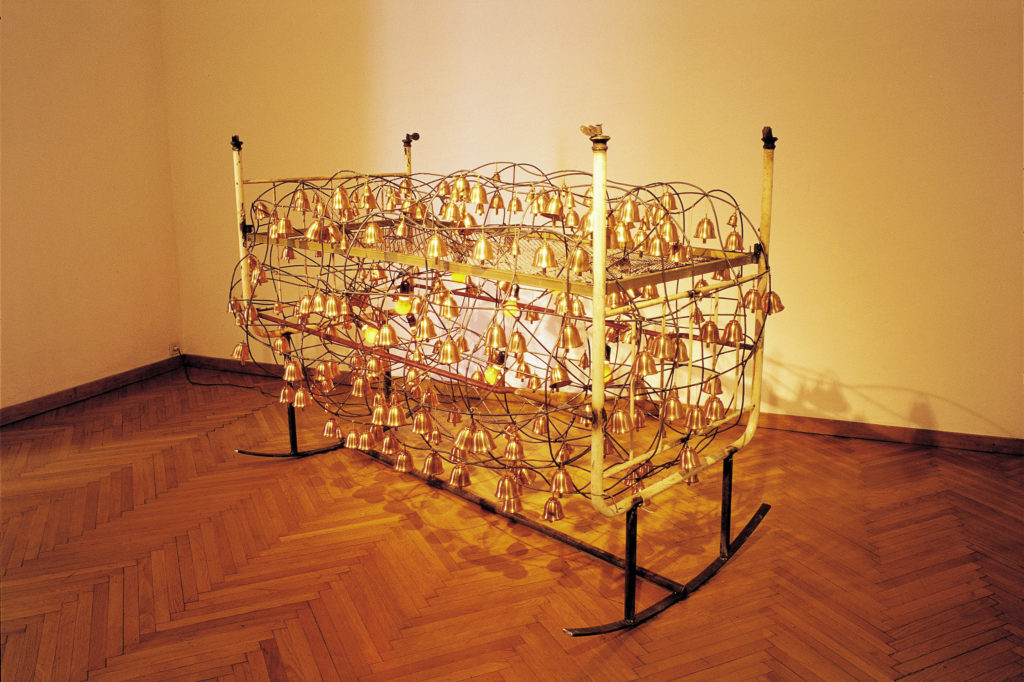

Chen Zhen, Six Roots (detail), 2000. Seven mixed-media sculptural installations in six rooms of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb.

Chen Zhen, Six Roots (detail), 2000. Seven mixed-media sculptural installations in six rooms of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb.

When I met Chen for the first time, he took my hand warmly with both of his. I immediately felt a connection. At first I felt awkward about my inability to converse with him in Mandarin. But unlike those who have challenged and even ridiculed me for this deficiency, Chen accepted me for who I am. He understood why my Mandarin-speaking mother decided that my brother and I would learn Cantonese and English rather than Mandarin: when I was growing up, Mandarin was not spoken in Vancouver’s Chinatown. Almost all of the Chinese people living in the city at that time had emigrated from Guangdong province in the south of China, where the Cantonese dialect is favoured.

Our dinner conversation kept returning to the topics of travel and identity. Chen’s ideas about travel were more complicated than the metaphor of the nomad, that boundary-defying muse of so much contemporary-art theory. He was more interested in thinking about acts of passage and laws affecting the immigrant. For Chen, migration has a moral dimension and can serve as a historical anchor; in this, his thinking is perhaps akin to that of Confucius, with his regard for China’s ancient past. Confucius saw the past as a place to which we must return in order to understand the present. As he would say, “Study the past if you would define the future.”

The intertwining of diachronic and synchronic time is a salient thread in Chen Zhen’s art. Many of his works use natural materials that powerfully convey the layering of time: earth, iron, wood, ceramics, foodstuffs, candles and cotton clothing. All of these materials refer to the lived world that they once occupied. In Chair of Nirvana (1997), several chairs are lashed together to form a latticed dome that provides shelter for a cradle. The weathered assemblage evokes a present community, but also makes reference to past lives. The title of the work calls up a third temporal state: that of eternal time.

Chen’s work also often invokes ideas of suspension and states of liminality. Chair of Nirvana is just one of many of his installations to employ materials that suspend or elevate other materials. String, rope and steel are used to render everyday objects liminal, with new orientations and meanings. Chairs often hover in mid-air in his work, so that their worn state is accompanied by a sense of transcendental endowment. Chen salvages them, imbues them with love and sets them on a new path, In Round Table (1995), chairs from five continents are brought together to form a new structure that evokes the round dining tables of Chinese banquet halls and restaurants. But the familiar arrangement is rendered strange by the ways in which the tables and chairs have been embedded into one another and stripped of their original function. In his analysis of Karl Marx’s discussion of the table in Das Kapital (1867), Jacques Derrida states:

This table has been worn down, exploited, over-exploited,

or else set aside, no longer in use, in antique shops or

auction rooms. The thing is at once set aside and beside

itself. … One no longer knows, beneath the hermeneutic

patina, what this piece of wood, whose example suddenly

looms up, is good for and what it is worth.

Chen’s table looms up too, but in a different way. It is no longer a table in itself, but has been altered so that a series of enigmatic significations emerge.

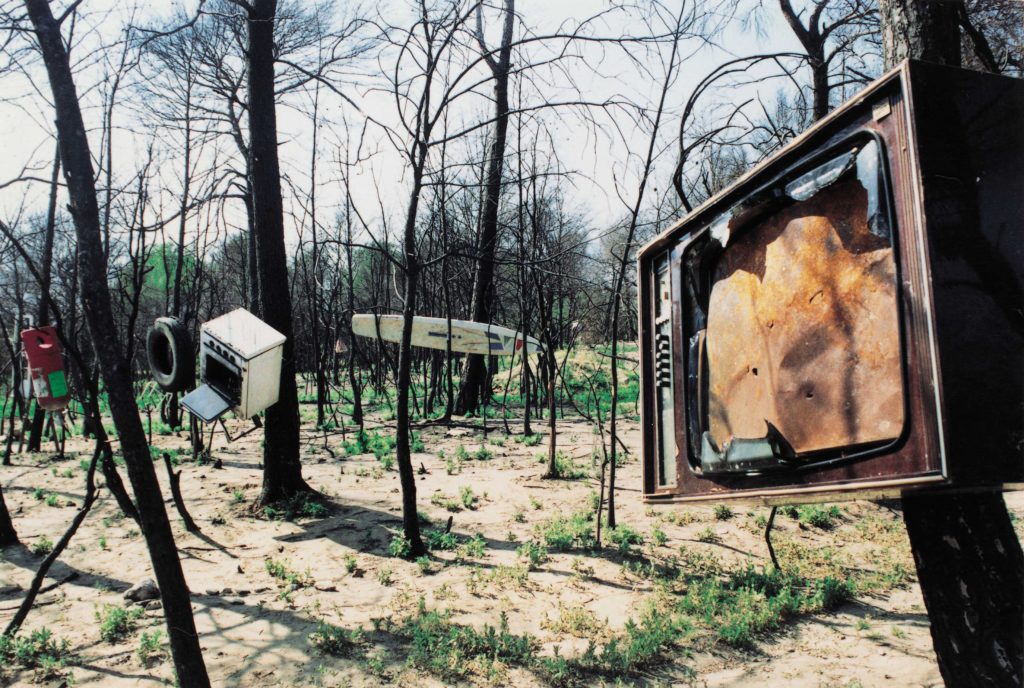

In other works, Chen employs a strategy of supplementation in order to draw attention to the paradoxical relationship between life and death. The supplement, according to Derrida, “comes to an aid of something original or natural.” As a device, the supplement is dependent on ambiguity; what is supplementary can always be interpreted in two ways. In Un monde accroché/détaché (1990), 99 found objects of varying sizes, devoid of use value and reclaimed from abandonment, are affixed to the branches and trunks of trees in a burnt forest outside of Paris. The denatured landscape gains visual and symbolic resonance through the affecting addition of everyday objects. The viewer is confronted with a strange, haunted landscape that embodies crossovers of two kinds: between the real and the unreal, on the one hand, and between completion and depletion, on the other. Chen’s objects reanimate the forest as well as functioning as a memento mori of that space.

Chen and his wife, the artist Xu Min, made a wonderful meal. (I recall Chen deftly handling the wok for one of the dishes.) He told me of his desire to become a doctor of Chinese medicine, so that he could heal himself of the disease that scourged his body and threatened his life. We talked at length about health and the spiritual dimension of life. I recall thinking about how spiritual Chen was, particularly in terms of his affinity with Chinese ontological precepts. Chen was not a man in search of wholeness, but one who understood the world as a whole, no matter how deficient or injurious it might be.

The body, health and medicine are syncretic terms in Chen’s art. As with the concept of yin and yang, the condition of illness contains within it the potential of health and well-being; the reverse is also true. At one point during the evening, Chen asked me if I had suffered illness or if there had been any illness in my family. I did not find his questions intrusive in the least. On the contrary, his caring curiosity was reassuring and caused me to think about my existence at that moment, as well as about my mother, who had died years earlier of leukemia, and my sister, who had never been given the chance to grow up.

Chen shared with me his experiences of illness. He told me that many members of his family were doctors, and spoke convincingly of the possibility of healing himself. This was conveyed with a modesty that I found striking. I sensed his belief that nothing in life was self-evident, and that one had no choice but to give oneself over to life at every moment. Chen has written, “I dream of discovering how the immune system is ‘a second brain,’ and how we can cure by being attentive to everyday experience.” He claims that “When one’s body becomes a kind of laboratory, a source of imagination and experiment, the process of life transforms itself into art.” This is a reminder of the profound interconnectedness of art and life, a concept that complicates the Western art-historical ideal, which dictates that the sublation of art vis-à-vis life represents a reconciliation of two estranged terms. For Chen, every day meant taking medications that would let him “keep a cool head” and make him “less proud.” He asserted that the project of becoming a doctor would be a synthesis of his life and the making of art.

Six Roots (2000) is an allegorical work comprising seven installations in six parts. The title refers to a Buddhist expression for the bodily senses. Chen borrowed this Buddhist theme to consider what he calls the “six stages of life and the many contradictory aspects of human behaviour,” focusing on the themes of birth, childhood, conflict, suffering, memory and death-rebirth. Significantly, death is presented not as the concluding stage, but rather as the setting for a transcendental re-emergence into life. Conflict and suffering (along with our memory of them) are present to remind us of the ineluctability of life in the here and now. Six Roots asks us to consider the following questions: how does memory operate in relation to a reordered life, in which there is disjuncture between past experience and present reality? What is the meaning of rebirth in the context of a haunted inner life and external circumstances that may be in conflict with one’s inherited values? And given the circularity of life, death and rebirth, are exile, displacement and loss permanent symptoms of identity creation and recreation? For Chen, harmony and reconciliation are ambiguous terms, effected by the passage of time and the accumulation of wounds.

Chen’s warmth and compassion seemed without end. At the time, his face was puffy due to the cortisone treatments he was undergoing, and this gave him a Buddhist aura. He was curious about what it was like for me to be Chinese, but born and raised outside of China. He told me that he had a sister living in Richmond, a suburb of Vancouver, and was fascinated by the important place Vancouver’s sizable Chinese population occupied in terms of the city’s social politics.

I told him that it had not always been this way. Chinese people could not vote in Canada’s federal elections until 1947; 1949 in British Columbia’s provincial elections. A federal law known as the Chinese Exclusion Act placed a head tax on all immigrants from China, effectively eliminating the migration of Chinese women and children to Canada. There were also laws prohibiting white women from working for Chinese-owned businesses (primarily restaurants and laundries). Several generations of Chinese men who had come to Canada and played an integral role in the building of the Canadian infrastructure died without ever reestablishing ties with the families they had left behind in China. Vancouver’s Chinatown is one of the oldest districts in the city; in contrast, Paris’s Chinatown is to be found some distance from the city’s historical centre. Today, Vancouver’s Chinese residents are established not only in Chinatown but throughout the city.

View of Vancouver’s Chinatown, 2007. Photo: Ken Lum.

View of Vancouver’s Chinatown, 2007. Photo: Ken Lum.

This history; with its suggestion that the unity of different peoples is indeed possible, seemed to satisfy Chen. For him, ethnicity was simply a category of mediation between groups that can only function in the context of a plurality of groups—one of ethnicity’s fundamental functions being its articulation of self and other. Chen’s references to Chineseness in his work had emanated from his own relationship to the world as an ethnically Chinese man, following on Stuart Hall’s belief in the necessity of recognizing that the figure of the migrant “comes out of particular histories and cultures and that everyone speaks from positions within the global distribution of power.”

It is important to consider how, in his work, Chen modulates notions of migration and ethnicity without reducing them to reified terms. Indeed, his use of these ideas is highly situational and allows for an examination of social identity on multiple levels. Much of Chen’s art is an expression of how ethnicity is a contingent, rather than closed, concept. In his work, individual subjectivity coexists in a complex fashion with the traditional Chinese concept of ontology, which envisions a heterogeneous synergy of being revolving around a binary yin/yang dialectic that abounds with philosophical agonism. At the heart of Chen’s art is the idea of self-actualization, something the Chinese writer Lu Xun deals with in his book Diary of a Madman (1918), in which he equates China’s turpitude at the beginning of the 20th century with the repression of the individual. For Chen, the experience of ethnicity is one of unending change.

In Precipitous Parturition (1999), bicycle frames and tires are assembled and suspended from rafters so that they appear to be a “dragon-snake giving birth to countless toy cars painted in black.” The work had its origin in the truism regarding China’s transformation from a nation of bicycles to a nation of automobiles. The mythic dragon is subjected to the prism of reality here: there is no masking of the work’s constituent parts or the support system in the rafters. The work conflates a pair of signifiers of Chinese identity—the dragon, an ancient symbol of Chinese culture, and the bicycle, a marker of Maoist modernity with links to social utopia. The toy cars in the installation play an ambiguous role: they are both rudimentary and parasitic, an army of insect-like vehicles that bridge the symbolic space of the bicycle-dragon and the real space of the gallery. There is an uneasy sense that the dragon, a symbol of power and divinity, is being swarmed by the little cars, and that it could be destroyed by them. Past, present and future are braided together in a tense, complex entanglement. Moreover, the materials and forms at play in the work are not unique to China’s experience of modernity; they have resonance for numerous regions in the developing world.

Chen was curious about the lives of those who had emigrated from China to British Columbia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. I told him about my grandfather, who arrived in Vancouver in 1907 and was one of the last of the coolie immigrants brought over to Canada to work on the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. I told Chen that my grandfather never forgave me for once accepting summer employment with VIA Rail, a government-run passenger rail service that took visitors to the Rocky Mountains. In light of what he experienced while building the railway, my grandfather saw my choice as a personal betrayal. I vividly recall Chen at that point expressing that migration imparts a violence that goes beyond the ideological inscription of social othering and stigmatization. He said that the experience has the ability to penetrate deeply into the individual’s physical body, to register on a cellular level.

Chen’s idea of the migrant as simultaneously eschatological and regenerating is a thread that runs through much of his art. In La Digestion perpétuelle (1995), new and used Chinese artifacts, such as abacuses, mah-jong tiles, electric fans, scales, vases and porcelain dishes, are loosely grouped upon a food turntable or Lazy Susan that is mounted on a dining table surrounded by chairs. The food turntable is frequently found on Chinese banquet tables; here, it invites the viewer to symbolically partake of the objects upon it in an eternal cycle of use and deterioration. Such ideas recur in Field of Waste (1994), whose conceptual axis is the binary relationship of degeneration and regeneration. The work comprises an assemblage of sewn-together garments and Chinese and American flags laid out on the floor in the shape of a wedge, which pierces an adjacent mound of charred newspapers (which resemble lumps of coal). At the base of the wedge are sewing machines similar to those found in sweatshops today. The components interact dialectically; there is ambiguity in terms of which one might be devouring the other.

Often overlooked in Chen’s work is its political content. The politics in Chen’s art operate as a reimagining of community that considers the specific case of China, and, by implication, the developing world’s relationship to modernity. It is a politics articulated in terms that are both concise and poetic. Field of Waste is very much an expression of anguish concerning the plight of garment-factory workers, many of whom are Chinese. According to Chen, the work introduces burning and sewing as opposing means of transformation. The first is revolutionary, destructive and chaotic, while the second is more constructive, and associated with reorganization and crossbreeding. Conceiving of the sewing process as a “plastic language” allows us to appreciate that the sweatshop has long been and still is a significant factor in survival for Chinese immigrants.

As someone who is a beneficiary of efforts made in the sweatshop—my mother, aunts and uncles have all worked in garment factories, and some of them still do—l am profoundly affected by Chen’s invocation of politics within the complex forms of his art. Very early on in my life I learned to understand the experience of the migrant in terms of social hardship and penury. I witnessed first-hand the psychic and physical damage that could be wrought by economic and racial exploitation. But in spite of the painful realities that often accompany the experience of migration, it is necessary to acknowledge the shifting contemporary definition of the migrant, in order to see all that may be possible in terms of the empowerment of the individual defined as a migrant. Salman Rushdie has written extensively on this subject:

The effect of mass migrations has been the creation of

radically new types of human being: people who root

themselves in ideas rather than places, in memories as

much as in material things; people who have been obliged

to define themselves—because they are so defined by

others—by their otherness; people in whose deepest selves

strange fusions occur, unprecedented unions between what

they were and where they find themselves.

Gayatri Spivak’s theory of “strategic essentialism” enables diasporic ethnicities—such as Chineseness—to identify with the idea of a return home, despite the fact that identity marked by hybridity renders home a highly problematized site of desire. It seems to me that this contradiction is what guides Chen’s art. He coined the term “transexperiences” to articulate “the complex life experiences of leaving one’s native place and going from one place to another in one’s life.” Leaving one’s native place for another place also implies, for Chen, a concomitant passing from this life to whatever may follow. For Chen, illness became a catalyst for his creativity. The yin/yang dualism of life and death and degeneration and regeneration became for him a defining dialectic, processes that Chen would diagnose through his art.

Towards the end of our dinner, I felt a bond with Chen that carried far beyond our common ethnic heritage. During a period of disillusionment for me, he reminded me of the necessity of seeking to form and express new connections in one’s art, especially in terms of the ways in which one inhabits the world. Above all, I think, Chen’s art is about questioning how one lives a life of love and purpose: love for the world and purpose in terms of one’s gift to the world. As I was about to leave the apartment that evening, I thanked Chen Zhen and Xu Min for the delicious meal. Chen gave me strength that day. I knew that I wanted to see him again, if only to selfishly feed off his passion. I knew that I had met someone special. As I walked out of his apartment into the Paris air, everything seemed that much more vivid, and I felt grateful for all that I saw around me.

Chen Zhen, La Digestion perpétuelle, 1995. Chinese chairs, wood, plexiglass, Chinese objects, framed documents and photos. Approx. 1.50 x 2 x 6 m. Collection Musée Léon Dierx, Saint-Denis, Reunion Island, France.

Chen Zhen, La Digestion perpétuelle, 1995. Chinese chairs, wood, plexiglass, Chinese objects, framed documents and photos. Approx. 1.50 x 2 x 6 m. Collection Musée Léon Dierx, Saint-Denis, Reunion Island, France.

Chen Zhen, Un monde accroché/détaché, 1990. 99 found objects hanged in a burnt forest, approx. 1000 m overall. Photo: Chen Zhen and Guan Huai Bing. Courtesy Galleria Continua, San Gimignano-Beijing.

Chen Zhen, Un monde accroché/détaché, 1990. 99 found objects hanged in a burnt forest, approx. 1000 m overall. Photo: Chen Zhen and Guan Huai Bing. Courtesy Galleria Continua, San Gimignano-Beijing.