Residue has a toxic connotation. Newscasters speak of ash left behind after a fire; police officers look for evidence, drug dust, at the crime scene. In social theory, the residual points to something in the past that lingers in the present. Artist Azza El Siddique leans toward this cultural-materialist meaning, even as her practice goes beyond the contemporary.

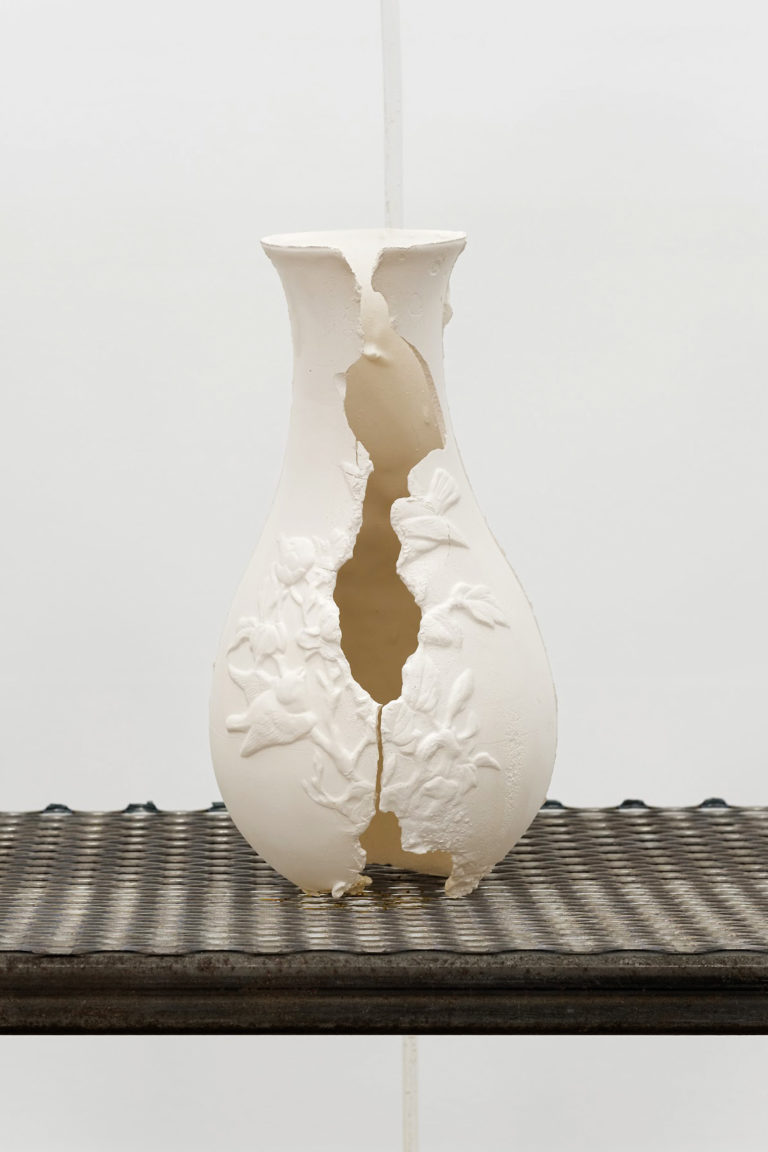

In the spring of 2019, at Helena Anrather in New York’s Chinatown, El Siddique showed “Begin in smoke, end in ashes,” a multi-sensory installation of light, sound and smell, stemming from her Yale MFA thesis project. In one geometric steel sculpture called What is left is only water (2019), she assembled cream-coloured slipcast clay vases that gently erode due to a slow-drip irrigation system allowing water to travel up through tubes from a pool framed by a square of grey cement bricks on the gallery floor. Inscribed on a single white brick among them: “BEFORE THE BIRTH OF TIME, SHADE AND A PLACE OF MEANING.”

Close-read the brick. Listen to the drip, drip, drip. Inhale. Scent, by way of flame-red heat lamps warming incense, is constant, wafting around the room, untethered from any particular sculpture. “Scent is such a powerful material,” El Siddique says. “There’s nothing like scent to throw you off-kilter—when you smell something that can take you through multiple states of time, that makes you feel disoriented and that brings a flood of emotions that engulfs you instantaneously. Scents seep into the walls, and these molecules are transferring and very fugitive. They also become a part of you, sitting within you and on you.” The result evokes the improvisation of ritual, even if it is performed under constraints—structural, like the gallery’s fire codes, or perhaps more interior, like the coercion of memory.

El Siddique re-forms her material remains in perpetuity: smoke, water, clay, glowing light, many of which—like clay mixing with water—transform hour by hour. Materials shifting, disappearing and refusing to conform is not a constructed formal tension as much as it is a possibility. “Things are calculated but at the same time it’s important to me for materials to have their own agency,” says El Siddique. “I don’t necessarily dictate how that form is going to collapse, where the water is going to penetrate, the way it decides to fall, the way it completely dissolves or the way it’s still standing but is missing a part. Those are the surprises.” Her aesthetic ecosystem reveals the way earth’s everyday natural processes (gravity, erosion, fire) contain a kind of magic.

Azza El Siddique, What is left is only water, 2019. Fired slip clay and rust, 30 x 20 cm. Courtesy Helena Anrather, New York.

Azza El Siddique, What is left is only water, 2019. Fired slip clay and rust, 30 x 20 cm. Courtesy Helena Anrather, New York.

Not every smell is included in El Siddique’s installation, but in her exquisitely crafted organic environments, it is almost possible to remember every smell: a grandmother’s mint tea, a putrid slaughterhouse, a ripening mango, an ex-lover’s fragrance. She tends to toggle between two scents in her art practice: sandaliya and bukhoor. She describes her engagement with sandaliya, a sandalwood oil used during the cleansing of bodies in Muslim burials, as invoking both death and the caretaking that happens because of it: the “ritual and care for the body as it transitions.” With bukhoor, a compressed incense made with wood chips and a secret recipe of sandalwood, myrrh, rose, frankincense and other fragrant oils, it’s clear El Siddique gets lost in how smell evokes personal memory and future care. “The first time I smelled bukhoor was in this Afghan supermarket in Toronto, and it reminded me of the diasporic Sudanese women who I had grown up with,” she says. “There was something that was so intoxicating, that just felt like it enveloped you in a comforting way. I think about women as unrecognized pillars of all these histories and legacies. My relationship to using that scent is not only as recognition or appreciation, but rather as a way of taking something invisible and letting it take up space.”

Born in Khartoum, Sudan, to a family who immigrated to Vancouver when she was four, El Siddique moved to Toronto where she briefly studied fashion design at Ryerson University, eventually graduating from OCAD University with a BFA in Material Art and Design. There, she spent a lot of time doing material exploration (“making fabric not behave like fabric,” as she put it) for her thesis. After a three-year residency at Harbourfront Centre in the textile department, and in the footsteps of her artist brother, who studied painting at Yale, she began an MFA in Sculpture at Yale University’s School of Art, where she would sometimes be in her studio for as many as 16 hours a day. El Siddique cites Yale alum Leslie Hewitt, an artist working at the intersection of sculpture and photography, as an important inspiration for her decision to apply. “I never thought of myself in a space like Yale,” she told me. “No one ever told me, ‘you’re a good artist’ or ‘you’re really smart’ or anything like that, but being there and seeing my brother who attended the painting program—his dedication to his practice and just seeing how much his work grew within that two-year period—that really inspired me and made me feel like it was going to be the space where I could grow as an artist.”

Throughout her practice, El Siddique has maintained a psychic canon, what she calls a “directory of materials,” a kind of archive of ways to use matter, ways to build, even as she is interested in what is left behind. “The residual is so important to me. How the work might leave a rust stain or the way matter is embedded in someone, in the walls, within a space. These relate to ideas of legacy: Who gets to participate?” Official history is often considered matter-of-fact, rather than carefully curated, rather than toxic. El Siddique politicizes the leftovers and remnants by engendering them with their own story, their own beauty.

After graduating from Yale this spring, El Siddique spent nine weeks in Maine at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and then travelled to Fishers Island, New York (a tiny, remote summer getaway for Connecticut’s and New York’s wealthy), for a six-week residency at Lighthouse Works. There, she worked on ceramics inside her sparse white studio, and did her metal cutting outside. On her studio walls, she hung colour printouts of ancient artifacts from the time of Nubian pharaohs—ancient Egyptian religious objects, queens and goddesses, mirrors, gold foils for a mummy’s fingers, canopic jars. Her interest in these objects arose from their quotidian quality, their intimacy marked by processes of social reproduction and caretaking (burials, rituals, dress), despite their ornamentation. “What happens if you really zoom in?” she asks. “There must be a particle of that person left behind.” On another wall hung a calendar; a drawing/tarot reading from a friend she met at Skowhegan; a written chemical breakdown of bukhoor, made by a graduate student in the Yale chemistry department; and a James Baldwin quotation from his 1972 non-fiction book No Name in the Street, laid out like a poem:

Well.

Time passes and passes.

It passes backward and it passes forward

and it carries you along, and no one in the whole wide world knows

more about time than this:

it is carrying you through an element you do not understand

into an element you will not remember.

Yet,

something remembers—

In late 2018, El Siddique exhibited “Let me hear you sweat” at Toronto’s Cooper Cole, where this same quotation provided the epigraph for the exhibition text. There, she showed some of her now-signature works, with steel sculptures and unfired clay and glass. She encased the metal shelving that held her clay objects with vinyl sheeting, and then used humidifiers to fill the partitioned space with fog, once again manipulating what is obscured and what is revealed.

A mix of fiction and non-fiction spurs El Siddique’s philosophical thinking while at the same time providing inspiration for her artistic practice. She reads contemporary theory, mythology and academic, often anthropological, articles about ancient Egyptian gardens and Ethiopian kings. And so much fiction. “I’ve always loved reading fiction. I literally wish everything was fiction. Or at least in the tone of fiction. Maybe the extent of reading so much fiction is essentially world-building in your mind, so when I read other, academic-type texts, this world-building starts to play.”

El Siddique’s unsteadying of Baldwin’s tight prose in her Fishers Island studio is a part of the unmaking at the core of her practice, an unmaking that is also a kind of making, a swaying between life and death. Especially death. In her installations, she looks for questions, not answers: “How do we reconcile with mortality? How has everything built on the power structure of mortality through religion, spirituality and science? Where does energy transfer to? How do we make meaning from death? What does it take to uphold a belief?” In her own way, El Siddique breaks out of the bleak sense of the residual, its relationship to the forensic, by rendering a radical investigative practice. She is relentless in her will to keep asking questions, to keep making art with the vestiges of life.

Azza El Siddique, Begin in smoke, End in ashes Pt. II (detail), 2019. Steel, expanded steel, water, unfired slip clay, enamel spray paint and slow-drip irrigation system, dimensions variable. Courtesy Helena Anrather, New York.

Azza El Siddique, Begin in smoke, End in ashes Pt. II (detail), 2019. Steel, expanded steel, water, unfired slip clay, enamel spray paint and slow-drip irrigation system, dimensions variable. Courtesy Helena Anrather, New York.

In raising these questions, it is clear that El Siddique knows that power as an institution touches not only the living but also the dead: “Religion, faith and spirituality are double-sided spaces that give us some sort of assurance that there’s something more, that there has to be more than this, but the ideas are so ephemeral. I’m interested in not only how these systems have been oppressive but also how they give so much comfort in attentiveness and care.”

El Siddique answers those questions through making and finding a poetic language within her installation practice. Her artistic process is similarly elemental: intuitive, iterative, introspective, almost frenetically quiet, and bears a relationship to the themes of ephemerality in her sculpture work. “I spend a lot of time in my head before I execute anything,” she says. “It’s kind of embarrassing when you walk into my studio, because you’re like, ‘Where is everything?’ I have a lot of things going on, but it’s all fragmented, and then things begin to crystallize in my mind.”

El Siddique’s work returns to the strictures and structures of the way the world moves—migrating populations, uneven temporalities and shifting (and shifty) histories. Histories hit you as scents can: Sometimes they come all of a sudden, and sometimes they seep in so slowly that you don’t even notice. They emerge like a slow creep, the trace that leaves its mark on social conditions. This is where El Siddique’s experiments live. On her relationship to art-making, El Siddique says that she’s “really grateful that people want to show my work and experience it, but when it boils down to everything, for me it’s really just about the making and exploring these complex ideas in a tangible way in order to make meaning of them.” Her work urges us to remember that even organic worlds are produced by making, and that even zones of disappearance and unseen temporalities are in fact produced. An alchemist turning brutal material beautiful and back again, El Siddique builds from that which is leftover: a whiff of incense, air dense with dispossession, water’s obsessive movement. Her installations require us to think deeply about the sensual extremities that trace those who came before us, continuously imprinting their ruins on the days ahead.

Azza El Siddique, Begin in smoke, End in ashes Pt. II (detail), 2019. Steel, sandaliya, bukhoor and heat lamps, dimensions variable. Courtesy Helena Anrather, New York.

Azza El Siddique, Begin in smoke, End in ashes Pt. II (detail), 2019. Steel, sandaliya, bukhoor and heat lamps, dimensions variable. Courtesy Helena Anrather, New York.