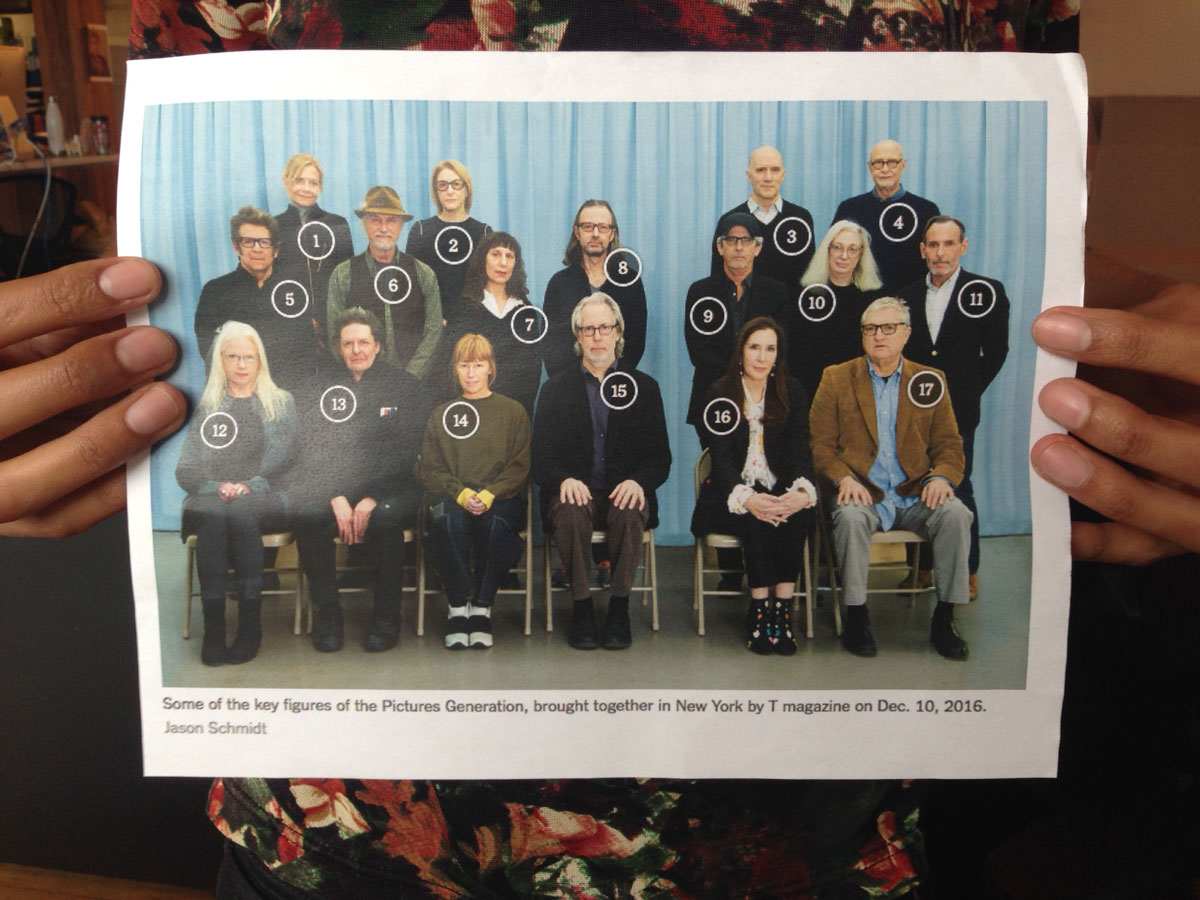

This summer, the artist Sara Cwynar attended a workshop at the Banff Centre for the Arts led by Claudia Rankine, the award-winning poet and founder of the Racial Imaginary Institute. Cwynar and her fellow participants in the residency were asked to “bring in a source text from [our] field, another field, or [our] own work in which race is absent, or in which race is present but whiteness remains unmarked, unnoticed.” Cwynar contributed an image depicting “The Pictures Generation”—a group of artists from the 1970s and ‘80s that were known for questioning authorship through the sampling of existing images, artworks and cultural artefacts. (The group photo was commissioned by the New York Times Style Magazine and published earlier this year.) The use of reproduction and restaging by the artists of the Pictures Generation not only undid conventional notions of artistic authorship, but also disturbed straightforward understandings of aesthetic value. Many of the original group are now very successful. All of the 17 artists the New York Times chose to represent as the best of this generation were white, and mostly male.

When Sara Cwynar, as part of a seminar program, was asked to bring in an example of an object in which whiteness remains unmarked, she brought in a printout of this image: Some of the key figures of the Pictures Generation, as brought together in New York by T Magazine in December 2016, and photographed by Jason Schmidt.

When Sara Cwynar, as part of a seminar program, was asked to bring in an example of an object in which whiteness remains unmarked, she brought in a printout of this image: Some of the key figures of the Pictures Generation, as brought together in New York by T Magazine in December 2016, and photographed by Jason Schmidt.

Cwynar, who is white, said she chose the image because of how clearly it belies race and gender as determining factors in professional success. Though Black and Brown photographers were also making work that fits within the definition of the Pictures Generation—such as Carrie Mae Weems, who was also the first Black woman ever to be selected for a solo exhibition at the Guggenheim—none of them have been retroactively attached to the movement. For Cwynar, the Times image was also a reminder of her experience at Yale, where she studied photography in the graduate program. “It was a very traditional photo program,” she says, “how the history of the medium [is taught], like most or all art histories, is very dominated by white men. Partly, it’s because what has been thought of as art photography—which legitimized itself in [an aesthetic of] painting when it started to be taken more seriously—was big painting-esque tableau photographs by people like Andreas Gursky or Jeff Wall.”

With their lavish, high-res production values, multi-person crews and elaborate set-ups, these were sorts of images that made Cwynar question whether she was in a position to make art photography at all—the barriers to entry seemed improbably steep. “It takes a ton of money even to get started,” she says. “It requires tools, it requires specialized knowledge, [access to which] has traditionally been very privileged.” When Cwynar began her practice a little more than five years ago, she admits to being part of a trend among younger photographic artists who eschewed any pretense of ambitious productions, in favor of “making stuff in the studio, making stuff smaller again.” Nonetheless, by choosing early on to shoot analog, Cwynar still faced against cost constraints. “I have always taken very few pictures,” she says. “Mostly because I can’t afford to take a ton of pictures if I’m going to make them the way that I want.” And yet, though cost has delimited the kinds of images Cwynar is able to create, it has also narrowed and brought into focus a space in which her practice can flourish. (Professionally, the slow, costly processing of film is the domain of a select few.)

In the body of work Cwynar has since amassed, her eclectic compositions use the very materiality of objects, their colors, shape, size, and connotations, to articulate a set of provocations. While her use of commodities alludes to their suffocating surfeit in our lives, it also allows for a larger questioning of what materials go into the processes of making works of art. The lushness of the photographs is disarming. They nearly tear objects away from their referent, and suggest a re-evaluation of the real material costs of production that are often overlooked in our consideration of aesthetics. When making artworks in particular, can it be possible to know how closely our valuation of aesthetics is linked to material production?

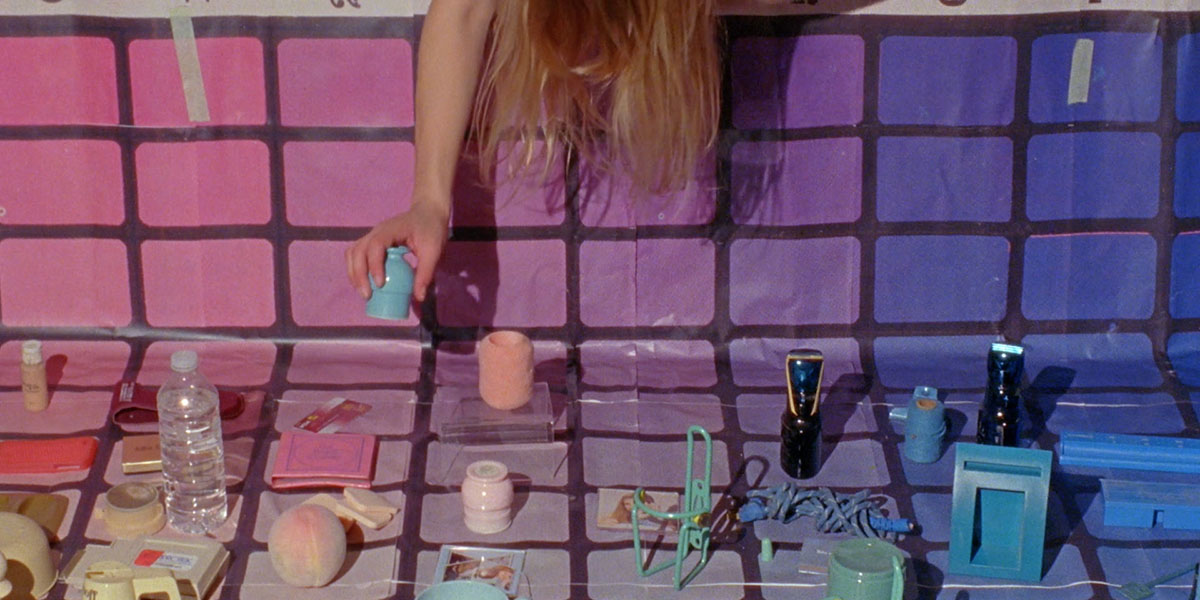

Sara Cwnyar, Rose Gold (still), 2017. Colour video, 8 minutes. Photo: Courtesy of TIFF.

Sara Cwnyar, Rose Gold (still), 2017. Colour video, 8 minutes. Photo: Courtesy of TIFF.

It’s debatable when exactly artworks become commodities. Theorist Isabelle Graw says it’s when a work gets sold. The artist and curator Anique Jordan says it’s when it enters the gallery or museum. Rarely when looking at art do we consider the cost of materials. We judge if it’s good or not and are perhaps aware of its financial worth; we talk about the market (dealer/collectors), secondary market (auction houses) and supply (artist’s artworks as commodities). But typically the mechanics of production, the material costs of creating an artwork’s value, are overlooked. Though we take it as a given that certain privileged identities (whiteness, maleness) have an ongoing monopoly on success—salability—we are still titillated by the unpredictability of market values for artworks. In the 1970s, applying a Marxian analytic to the social relations and economics of the art world, the American artist Adrian Piper suggested creative labour and the cost of materials should be factored into how we price works of art. She wanted labour time (whether it was thinking or making), and the costs of materials to be considered alongside allowances for secondary labour costs such as special accommodations and residual living expenses, like unforeseen illness. Her arguably apolitical approach suggested that fairness in an art system is technically possible.

Given the less privileged status of women artists, it’s not surprising, as Cwynar points out, that “the history of photography by women is much more about an economy of means. Using things that are immediately available and looking closely at everyday stuff, instead of making these spectacular tableaux photographs.” It’s this economy-of-means approach that Cwynar used to create Rose Gold. In this short film, she scrutinizes the color rose gold now most famously associated with the popular rose gold iPhone. Her indexical study of color plays with the distance between objects and their referent, between what things signify and how we feel about them. She traces the history of the color rose gold and its various significations and valuations over time.

Employing a tactic similar to the one used by the Pictures Generation, Cwynar repurposes cultural artifacts we unheedingly take for granted to arrive at a different understanding of what our culture values and holds dear. In the process, she delicately, beautifully, pulls apart our assumptions about what things ought to signify and how we feel about them. It’s an exploration characteristic of much of Cwynar’s work, reconsidering, as it does, what is assumed and unnoticed in our feelings about how objects look.

“The aesthetic value we accord to a work is also supposed to be independent of how much one may contemplate selling it for,” Piper wrote. She was neither naïve nor idealistic in her proposals for how we price works of art. If we can come to her premises with a better understanding of the disjunction between aesthetic valuation—that key to success—and the material conditions that enable it, our understanding of art might shift. It seems to me that what Cwynar offers, in Rose Gold and elsewhere, are tools for reconsidering the valuation of affect through the aesthetics of photo and film. She lays bare the material conditions for the production of film and photography, while reflecting also on the nature of those very assumptions that underlie those conditions.