The opening of “Àbadakone/Continuous Fire/Feu continuel” was electric. More than 3,000 people came to the National Gallery of Canada that evening—the largest attendance since the gallery’s opening in 1988. There were lines to get into the building, as well as lines to get into “Àbadakone.” The exhibition opened after performances of throat singing, drumming, hoop dancing and jingle dress dancing, as well as Métis jigging, which the crowd clapped along to. This was followed by a procession of the artists featured in the exhibition, coming from the lobby and culminating in the Great Hall, with Canada-based artists leading the way while drumming and singing. Each artist was announced as they entered the space, marking a momentous arrival, and making it clear that on this night, the National Gallery belonged to Indigenous peoples and Indigenous art.

Inuit throat singers Samantha Kigutaq-Metcalfe and Cailyn DeGrandpre, from the duo Tarniriik (Two Souls) performing at "Àbadakone" opening reception. Photo: NGC.

Following “Sakahàn” in 2013, “Àbadakone” is the second in an exhibition series that showcases global Indigenous contemporary art. What brings together the artists in this exhibition is a shared experience of colonization, and a shared directive to make art about Indigenous pasts, presents and futures. As a hegemonic world-making practice, colonialism exists by suppressing and destroying worlds that do not fit into its narrow ideals—worlds that present non-Western or anticolonial ways of knowing and being—through violent enforcement. The artworks in “Àbadakone” reflect on this suppression, as well as respond to it by recovering, presenting and celebrating numerous Indigenous worlds under the same roof. They echo artist Peter Morin’s words, spoken on a panel during the opening weekend: “My survival is intrinsically tied to your survival.”

The exhibition opening also coincided with the three-day conference Worlding the Global: The Arts in the Age of Decolonization. Organized by scholars based at Carleton University and co-presented with the National Gallery, it brought together artists and academics who were involved in the exhibition, and those whose practices relate to its themes. During one of its panels, curator Wanda Nanibush reminded those present that some audiences still have certain expectations of what art by Indigenous artists looks like, and suggested that contemporary art is a way to move beyond these stereotypical ideas. She shared, “It’s really important to push for who we are now and how we relate to that from an Indigenous perspective.” “Àbadakone” hopes to destabilize such stereotypes while showcasing examples of contemporaneous Indigeneity.

Maureen Gruben, Message, 2015. Polar bear guard hair, cotton thread, black interface. Collection of the Artist. Photo: Ming Wu.

Maureen Gruben, Message, 2015. Polar bear guard hair, cotton thread, black interface. Collection of the Artist. Photo: Ming Wu.

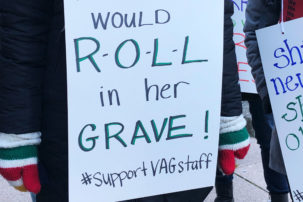

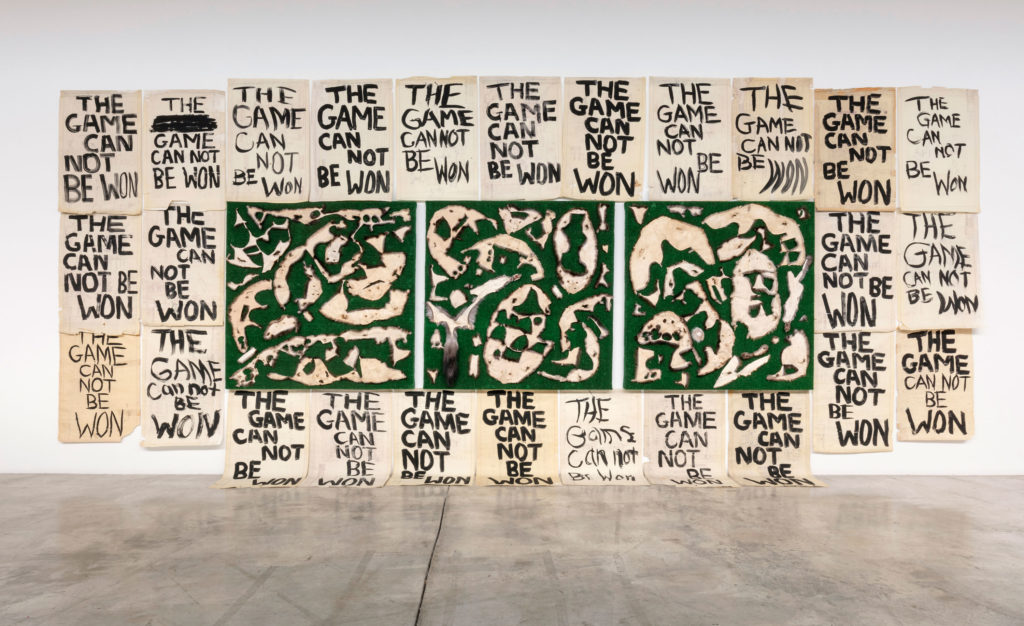

The artwork in the exhibition both reproduces and represents Indigenous knowledge, and brings attention to issues facing Indigenous communities today. Maureen Gruben’s Message (2015) spells out “SOS” in Morse code using polar bear guard hair, referring to changing climates in the Arctic and its effect both on polar bears and the Inuvialuit community. Ursula Johnson’s installation depicts drawings of baskets created by Caroline Gould, her great-grandmother, etched on empty acrylic vitrines. This work uses the language of museum presentation in order to contrast the museological conservation of Indigenous material culture as something static with the continued tradition of Mi’kmaq basketry. Manuel Chavajay’s and Joseph Tisiga’s works call to mind enduring violence faced by Indigenous communities. Chavajay’s Untitled (2017–18) addresses ongoing forced disappearances in Central America, and Tisiga’s repeating phrase “THE GAME CAN NOT BE WON,” painted on architectural plans of a residential school in Whitehorse, directs our attention to the colonial structures we still live in.

Ursula Johnson, Mi’kwite’tmn (Do You Remember?), 2014. Eight etched and sandblasted acrylic vitrines with birch face plinths. Collection of the Artist. Photo: Ming Wu.

Ursula Johnson, Mi’kwite’tmn (Do You Remember?), 2014. Eight etched and sandblasted acrylic vitrines with birch face plinths. Collection of the Artist. Photo: Ming Wu.

The National Gallery’s Christine Lalonde, Greg Hill and Rachelle Dickenson, with Canada-based curators Carla Taunton, Candice Hopkins and Ariel Smith working as consultants, curated “Àbadakone” with the help of a team of national and international advisors. One of the most challenging issues in curating an exhibition under a contemporary global Indigenous banner is being attentive to local contexts. Indigeneity is defined by local conditions and local histories of colonialism and imperialism, so curating works from all over the world in a way where these nuances aren’t lost among a global framework is incredibly important. During a tour of the exhibition, Hill said: “The idea of Indigeneity globally is not a universal notion, so that’s why we describe it as Indigenous nations, ethnicities and tribal affiliations. There are all these different terms that are in use in different areas in the world, and the application of one word to fit so many different contexts, it’s impossible and it’s colonial. I run into it almost every day: which word we use in English or French to represent all this, and I’m a little frustrated with it. I want to use the term Onkwehónwe, because that comes from my Indigenous language [Kanyen’keha], and that means the ‘Original Peoples.’”

Although there are many local differences, there is no denying that something significant happened at the National Gallery when Indigenous artists gathered from all over and spent time together. I felt an energy of solidarity and generosity during the first few days of the exhibition, where I saw artists sharing and learning together and with visitors. Discussions of collaboration and relationality occurred both at the exhibition and the conference, where the morning after the “Àbadakone” opening, decolonial scholar Rolando Vázquez asked the audience to think about the reception of art rather than its annunciation. He suggested we learn from First Nations philosophies in order to shift our perception of art as one based on the individual subject to one that is based on listening and reciprocity.

Pierre Aupilardjuk, Giving Without Receiving, 2016. Porcelain and smoke-fired stoneware, 23 × 45 × 22 cm. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada. © Pierre Aupilardjuk.

Pierre Aupilardjuk, Giving Without Receiving, 2016. Porcelain and smoke-fired stoneware, 23 × 45 × 22 cm. Courtesy National Gallery of Canada. © Pierre Aupilardjuk.

Pierre Aupilardjuk and Shary Boyle’s sculptural collaboration Facing Forward (2016) is on view in the first room of the exhibition. It shows a meaningful and reciprocal exchange of both artistic and cultural knowledge between Aupilardjuk and Boyle, where it is evident both artists are influenced by one another. In contrast, Aupilardjuk’s Giving Without Receiving (2016), installed beside this work, tells the story of a non-reciprocal transfer between Aupilardjuk’s family and a priest who took their source of heat and cooking, demonstrating the nature of colonial relationship as an extractive one. I also spent a lot of time exploring Joar Nango’s Sámi Architectural Library (2019). It is a tall makeshift structure taking over the lobby of the gallery that you can walk through and climb into while exploring recordings, videos and a collection of books about Sámi history and architecture, as well as anthropology, postcolonial and decolonial theory, space, temporality and gender, among other subjects.

The installation takes up this space and uses it to create community. Large rocks are scattered throughout the lobby to be used as seats for readers, and moosehide is stretched out and drying in the sun coming through the lobby windows. The work also includes a community makerspace, where the skinning, tanning and smoking of hides takes place a few steps outside the gallery’s main entrance. The hides are then sewn onto book covers, in a process Greg Hill understands as a way of “taking makers’ knowledge and wrapping that around the books.” Hill also shared that this project has drawn from the local Indigenous community with multiple people providing local hides and tending to the fire outside the gallery. After spending time in the library, I stepped outside, where a moosehide was being skinned and where other community members made soup over a fire. Artist Dayna Danger handed me a bone from the leg of the moose, which had been cut at an angle in order to remove the moose’s hair from its skin. The process was satisfying, and Danger showed me a spot where the hair comes off easily. After some time, Danger left and others approached. I handed someone the bone I was using and taught them how to skin the hide like I was taught just some moments ago.

Joseph Tisiga, installation view of An Exercise in Resilience 1, 2, and 3, 2016. Animal furs, artificial grass on plywood. And The Game is Not a Game, 2016. Mixed media on diazotype. Courtesy Diaz Contemporary and National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. © Joseph Tisiga.

Joseph Tisiga, installation view of An Exercise in Resilience 1, 2, and 3, 2016. Animal furs, artificial grass on plywood. And The Game is Not a Game, 2016. Mixed media on diazotype. Courtesy Diaz Contemporary and National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. © Joseph Tisiga.