Earlier this month, on a hot, humid Friday night, 700 artists, curators, musicians and art lovers converged on the newly expanded SAW Gallery in Ottawa to party into the wee hours.

There was good reason to celebrate. After years of hard work and planning, SAW—founded by local artists in 1973—was opening its new, triple-the-size space. The 15,000-square-foot facility includes a performance venue, bar/café, renovated outdoor courtyard and spacious exhibition facility—as well as a Nordic Lab residency for circumpolar artists due to launch in November.

SAW didn’t manage all this by going it alone. Director Tam-Ca Vo-Van and curator Jason St-Laurent say this transformation was a real community effort. That’s a generosity they hope to pay forward by sharing knowledge and helping other arts organizations expand, change and grow too.

Here are some key takeaways.

A view of the new SAW entrance. Photo: Leah Sandals.

A view of the new SAW entrance. Photo: Leah Sandals.

1) With new approaches, city government can be a vital ally.

“This was a City-led project, this whole precinct,” St-Laurent says. “The City was probably the biggest investor in this project, because they really wanted to make this happen—there was a lot of political will.”

Under a progressive model recently adopted by the City of Ottawa, SAW and other arts organizations in the new Arts Court, like Artengine, only have to pay rent on their office spaces—not on galleries or programming spaces.

“They had a precedent for that,” explains Vo-Van. “The Shenkman Arts Centre [in Ottawa’s east end] is a community-focused art centre where different organizations in the centre do programming and pay only office rent. [The City] decided they should to that consistently for all municipal facilities, so they made it happen for Arts Court.”

(That City support spurs other aid too: the local BIA provided funding to bring writers and critics—such as myself—in from Toronto and Montreal to see the new gallery.)

“We are really hoping this becomes a model for other arts facilities across the country,” says St-Laurent. “We used to have a fairly traditional lease agreement with the city…. But now we have a service agreement, because we are serving the community through programming.”

A new neon work by Joi T. Arcand is permanently installed in SAW's new bar/café space. Photo: Leah Sandals.

A new neon work by Joi T. Arcand is permanently installed in SAW's new bar/café space. Photo: Leah Sandals.

2) Building community means making efforts to speak the community’s languages.

Language and translation is a big part of SAW’s community-building. In recent years, SAW has taken its tradition of doing English-French translation of materials (not uncommon for arts organizations in Ottawa-Gatineau) and expanded it to other language communities.

“When we would have an artist of Chinese descent exhibit at SAW, the material would be translated into a third language, and we would send the info to Chinese community papers,” St-Laurent explains.

“When we presented a film and talk by Trinh T. Minh-ha in collaboration with the National Gallery of Canada, we did a lot of outreach with the local Vietnamese community,” says Vo-Van. That included creating communications materials in Vietnamese, and doing specific media outreach. “She told us she had never seen so many Vietnamese people at a talk of hers.”

Maylee Todd takes the stage in SAW's new performance space to kick off a monthly queer night series and the opening of the renovated gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

Maylee Todd takes the stage in SAW's new performance space to kick off a monthly queer night series and the opening of the renovated gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

3) As an arts organization grows, it needs to find ways to honour its roots.

One of the significant parts of the new SAW Gallery is its Art and Protest initiative. Launching this fall, the initiative will make a large semi-automatic screenprinting press, as well as materials and design expertise, available to collaborating activist groups at no cost.

“We were thinking a lot about the founders of SAW in 1973,” says St-Laurent. “They were activists, feminists, queers, all coming together. It was a very activisty space…and we wondered whether [those folks] would recognize themselves in the new SAW. That was always in the back of our minds.

“Also,” says St-Laurent, “we’re in a political town, and there are protests happening all the time. There are good people doing work for social change. We were like, how can we elevate that? And then we thought, maybe we can elevate that through art and design.”

The inaugural exhibition in the new space, “Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing” is also related to that history of protest and resistance, featuring bold works by Cindy Baker, Panos Balomenos, Dave Cooper, G.B. Jones, Sholem Krishtalka, Zachari Logan, Kent Monkman, Diane Obomsawin and Mia Sandhu.

“Some people worried that SAW would institutionalize [with this expansion] and in a way, with a new facility, you can’t help that,” says St-Laurent. “So when we were planning what we were going to do with our exhibition schedule, we thought we should do something that sets the tone for the new SAW—the fact that we haven’t changed much. We have a long-standing relationship with the queer community here, and we thought, maybe this is the perfect show for SAW to open with.”

At the opening of the exhibition “Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing,” during the launch of the new SAW Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

At the opening of the exhibition “Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing,” during the launch of the new SAW Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

4) You can get a lot of support from your arts-organization peers. It doesn’t always have to be a competition for resources.

For many years prior to the Arts Court redevelopment, the Ottawa Art Gallery and SAW Gallery were neighbours. Now they are again, each in a new or renovated facility. And a spirit of neighbourliness was vital to making the SAW renovation happen.

“The Ottawa Art Gallery have given us so much great advice,” says St-Laurent. “As we got closer and closer to the opening, they started giving us access to all their staff—from curatorial staff to technicians. And then the OAG mandated their staff to help us out. They ordered food for 15 people every single day to make sure we were eating well leading up to the opening.”

“They also extended their child care services for our opening,” says Vo-Van. “And earlier on they shared their procurement policies with us, so we were able to include that in our grant applications.”

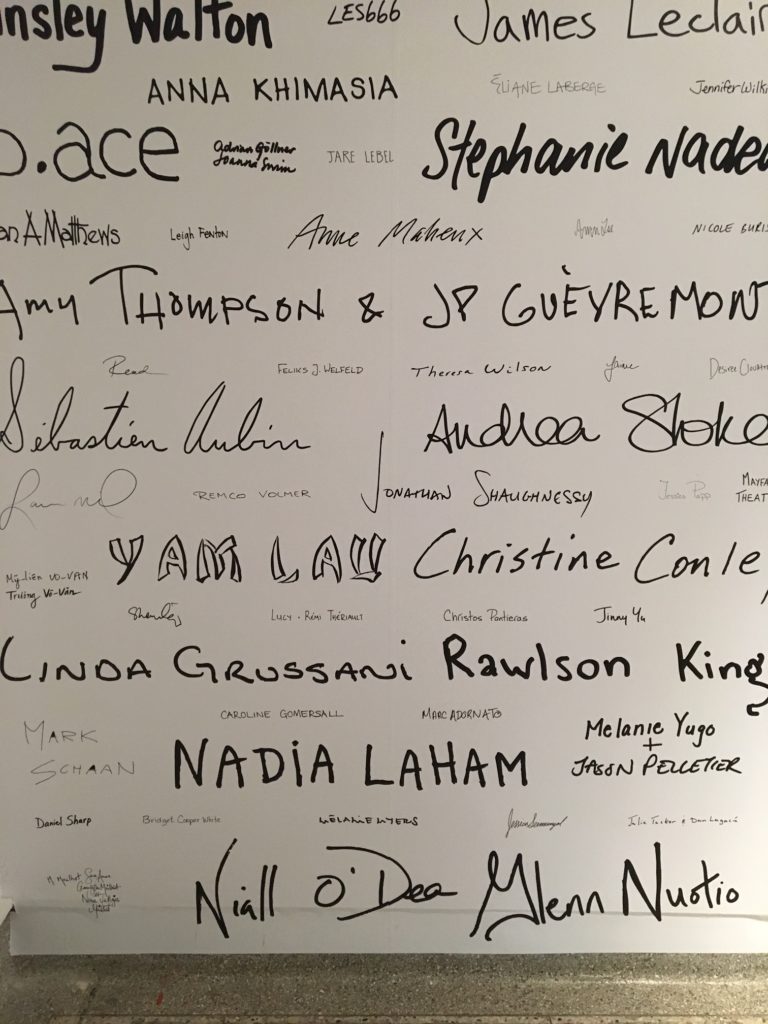

Part of the donor wall at the new SAW Gallery. Each donor hand-wrote their name and it was printed in proportion to their donation amount. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Part of the donor wall at the new SAW Gallery. Each donor hand-wrote their name and it was printed in proportion to their donation amount. Photo: Leah Sandals.

5) Expect to access—or develop—multiple funding streams and backstops.

Funding for the new SAW and its programming was made possible through many sources: the Canada Council, the Ontario Arts Council, the Trillium Foundation, the Canada Cultural Spaces Fund and the City of Ottawa, to name a few.

“Have a healthy reserve fund” is one of Vo-Van’s first pieces of advice for others embarking on an expansion. “You need it for every unexpected expense that comes up—because it will come up, whether you want it to or not.”

Private sources of funding and artworks were also important on various levels: from the fact that the Arts Court redevelopment is a PPP (private-public partnership) with a local real-estate developer, to the gift from a local collector of a wall full of General Idea AIDS prints, to smaller, out-of-pocket donations from artists and locals, which are honoured on a wall near the gallery offices.

“We didn’t want to go the corporate route in terms of funding, and we didn’t want to sell naming rights,” says St-Laurent. “So we decided to launch a capital campaign with very, very small donations from people. Most were $50 donations—and for us, that was pretty special, because most artists don’t even have $50 to give.”

And the new SAW Art and Protest initiative is being supported by proceeds from the bar. “The idea is to give us more freedom, through self-generated revenues, to do programming that we don’t have to tailor to a particular project grant,” St-Laurent explains. “With the profits from the bar, we want to invest in initiatives we couldn’t necessarily get [other] funding for.”

A sculptural work by Zachari Logan is featured at the opening of "Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing" at SAW. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

A sculptural work by Zachari Logan is featured at the opening of "Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing" at SAW. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

6) Find the right model for your organization—and once you do, reach out to role-shadow or learn more.

The new SAW integrates performance and gallery, bar and social space. It’s a lot, and it stretches beyond what SAW once was.

“I think for someone who wants to embark on a project like this, it’s important to look at the right kind of model,” says St-Laurent. “We weren’t finding the right model for ourselves in artist-run centres, so we modelled a bit on Buddies in Bad Times [Theatre] in Toronto.”

Once they found their model, SAW staff took steps to learn directly from Buddies. “We had some of our staff shadow some of their staff for a while,” says St-Laurent. “And that was probably one of the most useful exercises in building this multidisciplinary space.”

Buddies also had a key insight for the SAW performance space that architects hadn’t considered: “double glazing the windows,” says Vo-Van. (It’s a design solution reduces sound transfer of indoor performances to passersby or neighbours outside.) “So we talked to the city about that idea, and the city accepted our proposal.”

Vo-Van says that advice doesn’t have to come in a formal consultation context. Casual or informal conversations are important too.

“Having the chance to talk to Gallery TPW about their capital project, we got so many incredible tips that really helped us improve our project,” says Vo-Van. “A lot of their very specific recommendations around lighting and acoustics came back to our project.”

Visitors consider Diane Obomsawin's work at the opening of the exhibition “Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing,” during the launch of the new SAW Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

Visitors consider Diane Obomsawin's work at the opening of the exhibition “Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing,” during the launch of the new SAW Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

7) Practice patience, and try to find the silver lining in delays.

Any building and expansion project, especially one with so many stakeholders, takes a long time. “We should try to count the meetings we have had about this over the past seven years,” laughs St-Laurent.

The new SAW was due to open in fall 2018, but a construction delay forced it to summer 2019. That ended up being a good thing.

“That [delay] made more opportunities for artists to produce new works” for the opening exhibition “Sex Life,” St-Laurent points out. “Half of that exhibition is brand new works.”

At the opening of the exhibition “Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing,” during the launch of the new SAW Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

At the opening of the exhibition “Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing,” during the launch of the new SAW Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

8) Once the building finally opens, get ready to pay it all forward.

“Now people are coming us, saying, ‘We’re thinking of doing a similar project,” says St-Laurent. “We’ll gladly share all our grants that we put in to different funders—we can just give them the package, share all that information.

“Now we want to help others, pay it forward,” says St-Laurent, “because building a vibrant art scene helps everyone.”

This article was corrected on August 1, 2019. The original incorrectly indicated that double-glazed windows were used to prevent passerby and neighbours from inadvertently seeing performances. In fact, these windows were used to prevent neighbours and passerby from inadvertently hearing performances.

Visitors consider Sholem Krishtalka's installation at the opening of the exhibition “Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing,” during the launch of the new SAW Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.

Visitors consider Sholem Krishtalka's installation at the opening of the exhibition “Sex Life: Homoeroticism in Drawing,” during the launch of the new SAW Gallery. Photo: Justin Wonnacott / SAW.