The world’s largest photography festival is Canadian: Contact, which happens in galleries, public spaces and alternative venues throughout Toronto every May. The festival’s extensive program of exhibitions, public artworks, talks and more launches this week; here are a few of the projects on our must-see list.

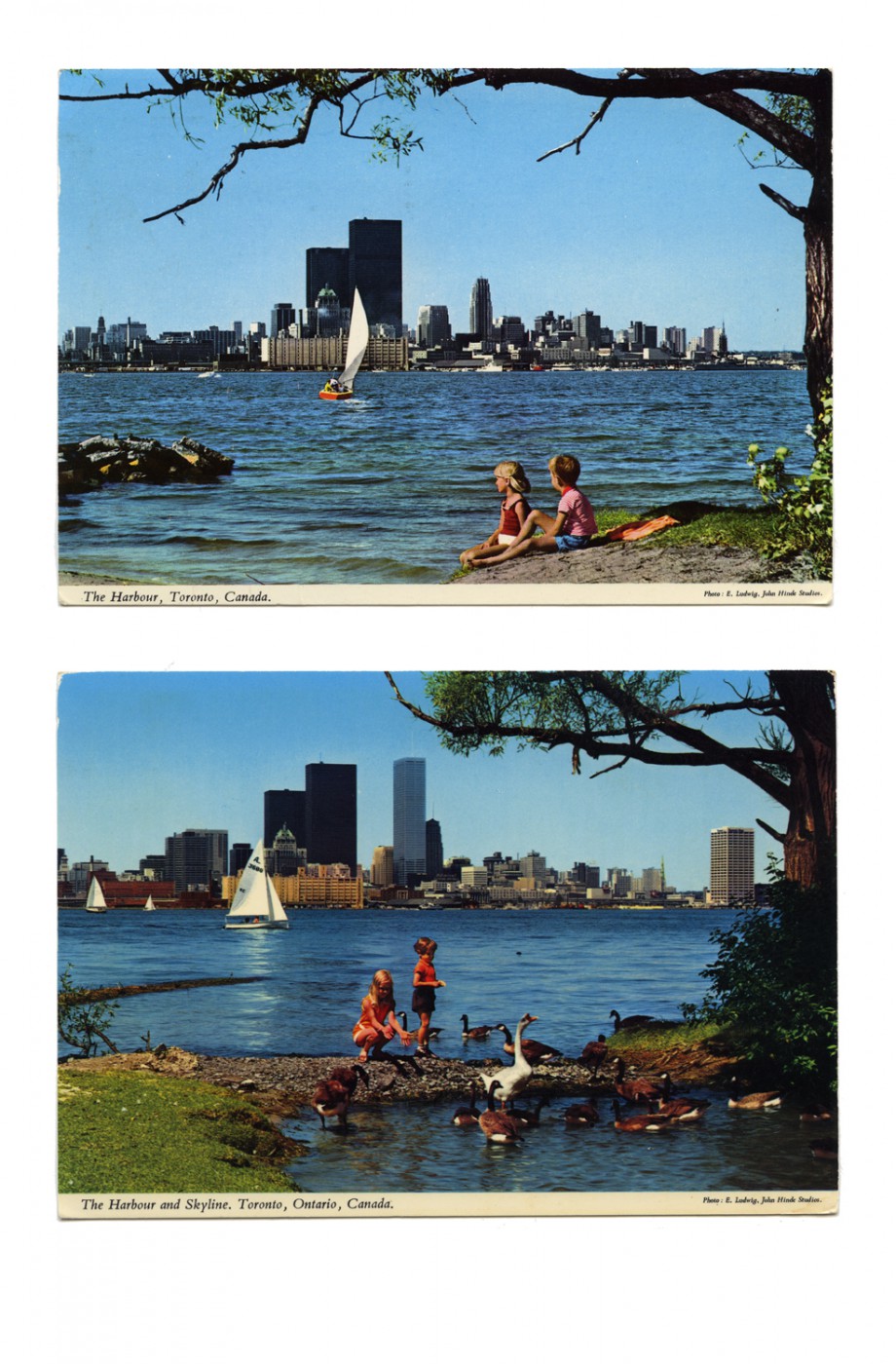

Luis Jacob, Sightlines, 2017. Vintage postcards. Courtesy the artist.

Luis Jacob, Sightlines, 2017. Vintage postcards. Courtesy the artist.

Luis Jacob’s “Habitat” at Gallery TPW, May 5 to June 10

Luis Jacob’s commitment to Toronto and its histories is impressive, necessary, and continues to gloss his practice. For this year’s Contact, Jacob presents a new version of his Album series, in theory a simple exercise of the artist clipping images and arranging them to form philosophical narratives. Though Toronto has always featured in the Album series, this one, Jacob’s fourteenth, promises a more concerted focus on local infrastructure and artists. The experience of a Jacob Album always adds up to more than the technical concept or individual images—similar to Toronto, a city whose pleasures often defy its seemingly prosaic, component parts. Two other works accompany this Album: selections from Jacob’s collection of Toronto postcards, and a collaboration with erstwhile Honest Ed’s sign-maker Wayne Reuben.—David Balzer, editor-in-chief

Celia Perrin Sidarous, Alcyonacea, 2017. Inkjet print on matte paper, 45 x 37 inches. Courtesy the artist and Parisian Laundry.

Celia Perrin Sidarous, Alcyonacea, 2017. Inkjet print on matte paper, 45 x 37 inches. Courtesy the artist and Parisian Laundry.

Celia Perrin Sidarous’s “a shape to your shadow” at the Campbell House Museum, May 3 to June 10

In 17th-century Dutch still-life painting, flowers blooming in different seasons and locations were often presented alongside one another. This theme of the impossible bouquet is also found in the art of Celia Perrin Sidarous—still-life assemblages of wallpaper, coral and leaves, for instance—and in the architectural fabric of Toronto. It seems fitting that the Montreal-based artist was offered the chance to intervene inside the Campbell House Museum, a Georgian home from 1822 located between a Starbucks and University Avenue across from a Rexall—itself a kind of impossible urban bouquet. Sidarous’s house-wide arrangement—comprised of new and existing works occupying hallway cabinets, historic portraits and mantlepieces—replants these histories out of time and place, giving us the chance to see them bloom briefly, together.—Evan Pavka, intern

2Fik, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 2010. Archival pigment print. 38 x 50 inches.

2Fik, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 2010. Archival pigment print. 38 x 50 inches.

2Fik’s “His and Other Stories” at the Koffler Gallery, April 6 to June 4

What do you do when the images you consume—moving or still, high or low, ambient or private—never reflect your image back to yourself? You superimpose yourself on them. 2Fik’s “His and Other Stories” shows the Paris-born, Montreal-based Moroccan performance artist and photographer persisting to self-represent in several bodies of work. In 2Fik’s Museum, he embodies Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque, but with a feather duster, rose-quartz rubber gloves and beard intact. In another image, he is all three characters in Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe, while behind the picnickers, Fatima, a fictional character who recurs throughout 2Fik’s tableaux, makes an appearance. 2Fik’s fabrication of fiction with fashion fucks with any leftover conceptions that identity ought to be a static and mutually exclusive personality-quiz result.—Merray Gerges, staff writer

Meera Margaret Singh, Bound, 2012. Chromogenic print, 30 x 45 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Meera Margaret Singh, Bound, 2012. Chromogenic print, 30 x 45 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Meera Margaret Singh’s “Jardim” at Zalucky Contemporary

In “Jardim,” Meera Margaret Singh’s practice turns from her signature portraiture towards the non-human. Photographed in 2012 during a two-month residency at Jardim Canada, a small industrial town in Brazil, these images frame decaying surroundings—warehouse walls, vegetalia, weeds, cacti, clay, dirt, fences—as their centre. Bodies and faces of the town’s inhabitants, both wage-labourer and passerby, only scatter the edges of stills; they are few and far between, and almost never captured up close. “Jardim” could be a turning point for Singh; it presents a puzzling inaccess to gesture and expression, in a foreign environment that veers between home and the inhospitable.—Aaditya Aggarwal, web intern

Shelley Niro, Sullivan Campaign, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Shelley Niro, Sullivan Campaign, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Shelley Niro’s “Battlefields of My Ancestors” at Fort York, Ryerson Image Centre and Ryerson University, starting April 28

Today, Ryerson University markets itself as a champion of “diversity, entrepreneurship and innovation.” But few realize that its founder Egerton Ryerson (1803–1882) influenced Canada’s Indian residential school system, which had a devastating impact on First Nations communities. During Contact, Shelley Niro’s photos of historical plaques and contemporary landscapes where her Mohawk ancestors once fought will flank the bronze sculpture of Egerton Ryerson on his namesake university’s campus, making his more problematic legacies visible. Her photos will also appear at Fort York, a contested site that many First Nations warriors nevertheless defended during the War of 1812. And, lest we forget the role of Aboriginal soldiers in other “Canadian” wars, Niro includes an image of Vimy Ridge, too.—Leah Sandals, managing editor, online

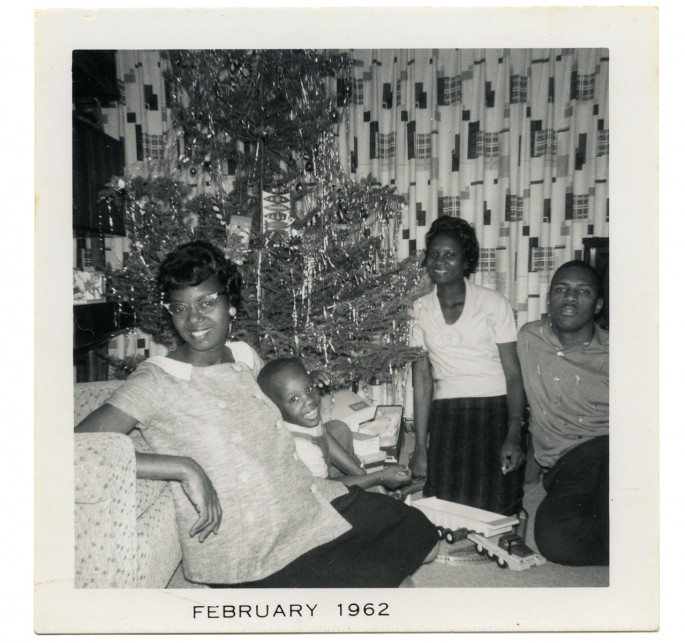

Photographer unknown, Ellen Montague and her son Christopher; her sister Ruth Brown; and her husband Spurgeon Montague beside the Christmas tree, Windsor, Ontario, December 25, 1961. Courtesy of Dr. Kenneth Montague.

Photographer unknown, Ellen Montague and her son Christopher; her sister Ruth Brown; and her husband Spurgeon Montague beside the Christmas tree, Windsor, Ontario, December 25, 1961. Courtesy of Dr. Kenneth Montague.

“The Family Camera” at the Art Gallery of Mississauga and the Royal Ontario Museum, May 4 to August 27

Family photo albums do more than tell personal histories. In Canada especially, they construct vivid pictures of migration and the particular ways cultures meld. This exhibition puts on view more than 200 objects amassed by the Family Camera Network, a public-archive project, and exhibits them with new works by Jeff Thomas, Deanna Bowen and Dinh Q. Lê. It takes on serious subjects, such as how family photos can combat state propaganda, how diverse families are structured and how some families were ripped apart by residential schools. It explores how tourist snaps can be a way of claiming a sense of belonging in a new nation, and how we follow common conventions of posing for milestone events. Perhaps most importantly, as in the image of a little girl with her arm around a dachshund, it proves that everyday moments at home are landmarks in themselves.—Rosie Prata, managing editor

Luis Jacob, Photographer Unknown, Unidentified Woman, 1860-1880. Tintype, 8.9 x 6.4 cm. Richard Bell Family Fonds, Brock University Archives. Courtesy Brock University Archives. © Art Gallery of Ontario.

Luis Jacob, Photographer Unknown, Unidentified Woman, 1860-1880. Tintype, 8.9 x 6.4 cm. Richard Bell Family Fonds, Brock University Archives. Courtesy Brock University Archives. © Art Gallery of Ontario.

“Photography Collection: 1840s to 1880s” and “Free Black North” at the Art Gallery of Ontario, April 27 to December 31 and April 29 to August 20

At the AGO, curator Sophie Hackett unveils the first in a series of rotating exhibitions highlighting the gallery’s rich photography collection. Gathering vintage images from the 1840s to 1880s, the exhibition not only tracks the advent of photographic practices and how the medium was employed on a global scale to record colonial ambitions, tourist whims and natural wonders, but also the innovative and often whimsical presentation techniques that push these rare images beyond the frame—most notably in the ornately carved Tramp Art Photo Display (ca. 1855) found in Orillia, Ontario, in 2011. Also at the AGO is “Free Black North,” curated by Julie Crooks, which assembles a series of tintype studio portraits of descendants of Black refugees from the United States. The names and histories of the sitters for these images remain mostly unknown, but together they offer a counter-narrative of style, dignity and self-assurance in the face of historical trauma.—Bryne McLaughlin, senior editor

Tania Willard, Only Available Light, 2016. Selenite crystals, archival film. Courtesy of Grunt Gallery.

Tania Willard, Only Available Light, 2016. Selenite crystals, archival film. Courtesy of Grunt Gallery.

“What does one do with such a clairvoyant image?” at Gallery 44, May 5 to June 3

Whose histories are present in the Canadian imaginary, and at whose expense? The artworks in this show employ a speculative imaginary that reclaims alternative histories of Turtle Island—forcing the viewer to contend with their relationships to the land they stand on, perhaps uneasily. Tania Willard projects anthropological depictions of her Secwepemc ancestors on film, disrupting their projection with selenite crystals—a mineral form of gypsum, which is an ingredient of plaster—thereby disrupting the film’s viewing and its objectifying settler lens. In doing so, Willard frees her people from the plaster casts that hoard their bodies in museological archives. And she’s just one of several artists in this exhibition reclaiming vast Canadian landscapes for those who have been dispossessed of them.—Lindsay Nixon, Indigenous editor-at-large

Steven Beckly, Untitled, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Steven Beckly, Untitled, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Steven Beckly’s “New Romantics” at Dovercourt Road and Dupont Street from May 1 to 31

Since I moved into the neighbourhood years ago, a glass-box warehouse at the corner of Dovercourt and Dupont has caught my eye. I knew it couldn’t last in its state of disrepair given the city’s pace of development, and this was confirmed when Bellwoods Brewery announced in 2014 that the building would house its second location. But the corner still feels unchanged, which is partly why I’ll be walking over to see Steven Beckley’s billboard project. The images possess the quiet intimacy that marks Beckley’s practice—arms locked together, shadows thrown across empty spaces—and the results of their own diffuse lighting mixing with that of the glass building will undoubtedly be beautiful. For a little while, they’ll transform a space that faces major and irrevocable change, but in an entirely different fashion.—Caoimhe Morgan-Feir, associate editor

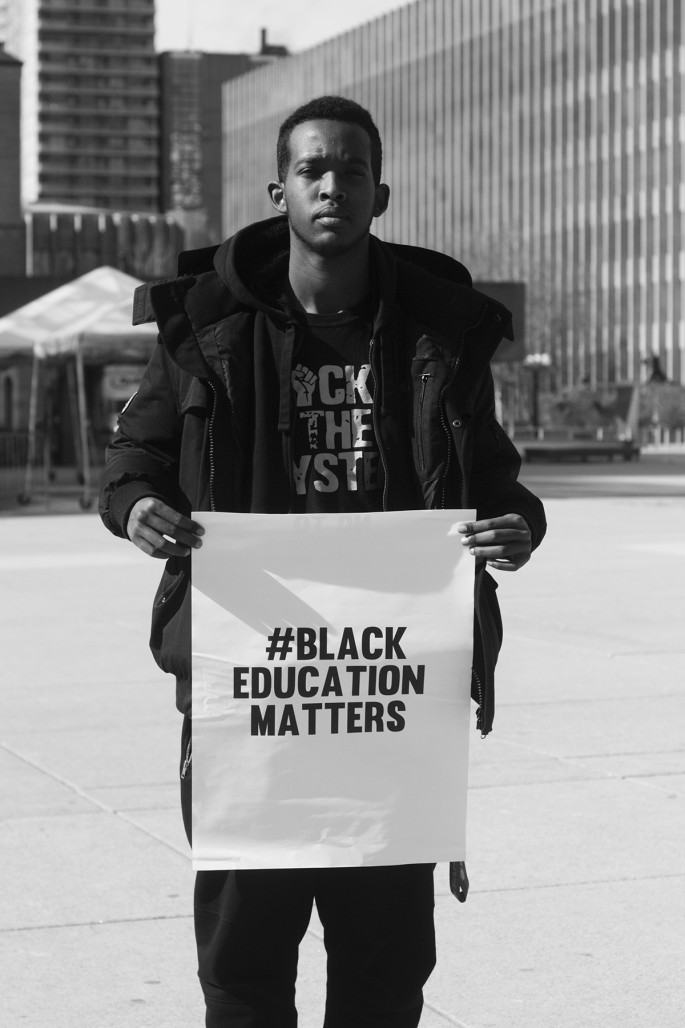

Jalani Morgan, Untitled (A demand to end police carding: Hashim Yussuf poses for a portrait after they ‘ran up’ on Mayor John Tory), Toronto, Canada, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Jalani Morgan, Untitled (A demand to end police carding: Hashim Yussuf poses for a portrait after they ‘ran up’ on Mayor John Tory), Toronto, Canada, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Jalani Morgan’s “The Sum of All Parts” outside Metro Hall, April 28 to May 31

For a few years now, Toronto photographer Jalani Morgan has been documenting events including the Black Canadian Studies Association Conference, the Racialized Indigenous Student Experience Summit and Black Lives Matter TO rallies and protests. This urgent, important work is bound to be more visible—and potent—than ever when it’s installed on large placards outside Metro Hall. Metro Hall, of course, was once a hub of municipal government, and it remains in use by municipal employees today. “The symbolic siting of Morgan’s work at Metro Hall allows viewers to consider the status of [Black Lives Matters TO’s] demands against political backdrop,” curator Emelie Chhangur writes, “and how difference and negotiation will act as mobilizing factors in creating new kinds of solidarities for this city’s future.”—Leah Sandals, managing editor, online

Anil Dewan, Barbara with her kids Naina and Arjun, and grandma (daddi) Indira, who is visiting from India, Niagara Falls, August 1980. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of Deepali Dewan.

Anil Dewan, Barbara with her kids Naina and Arjun, and grandma (daddi) Indira, who is visiting from India, Niagara Falls, August 1980. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of Deepali Dewan.