Gillian Dykeman

As part of her 2016 master’s thesis exhibition, Fredericton artist Gillian Dykeman presented the video Dispatches from the Feminist Utopian Future within a larger installation that imagined various canonical earthworks from the perspective of the future. It’s a project that addresses the inherent sense of timelessness in these massive interventions on the natural landscape from the perspective of contemporary land politics. The accompanying bookwork, On the Road/Psychic Strata, is a diaristic response to her experience of visiting these monuments to modernism, and to the contemporary lives and economies that surround them. For Dykeman, earthworks presuppose that the land is empty and available, open for anyone’s use, but within what she calls “a climate of artistic accountability,” she refuses to give these sites, or their contemporary equivalents, a pass. The video begins with a timelapse of a sunrise, with the subtitled text “what is it like to wake up in the feminist utopia?” It continues with durational views of the landscapes that contain iconic 1960s earthworks, with Dykeman present—running, jumping and frolicking in a royal-blue jumpsuit. As she runs across the gravel length of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) and climbs through Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1976), she proposes a kind of interaction with the invasive and often colonial gestures of modernist Land art, one that imagines a different future for these earthworks, where they are treated as alien in a landscape and as beacons from a feminist future.

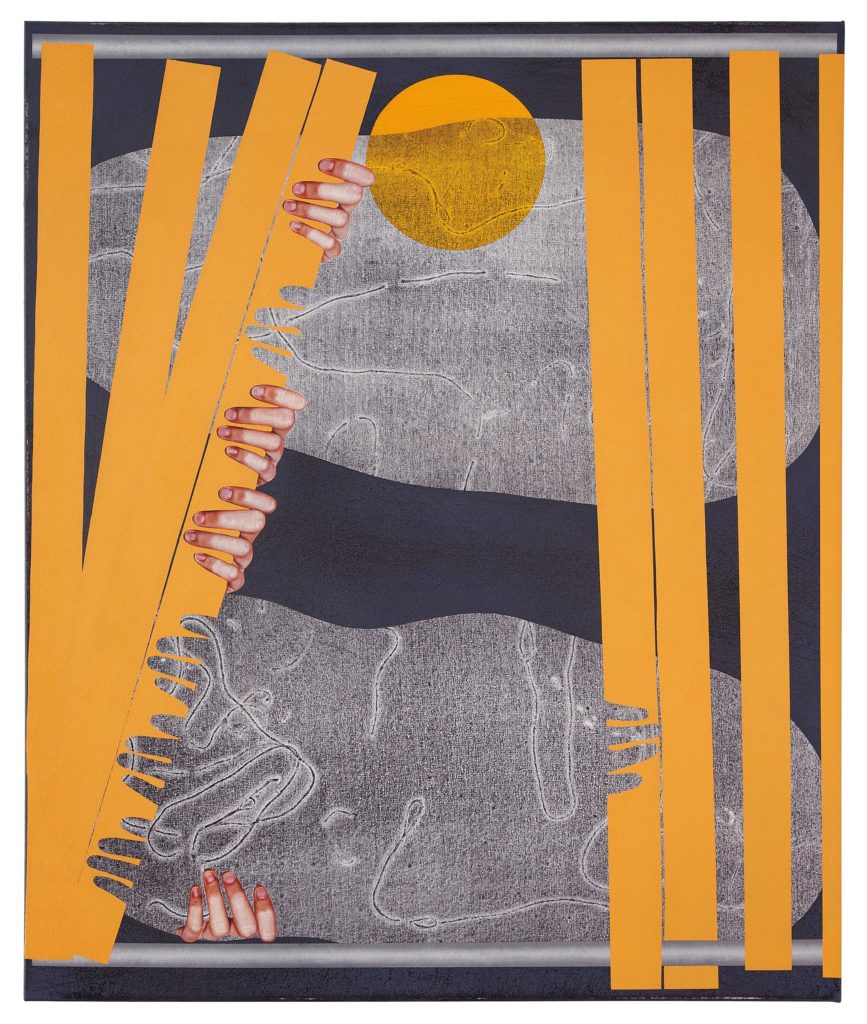

Veronika Pausova, Contact Lens, 2018. Oil on canvas, 91.4 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Veronika Pausova, Contact Lens, 2018. Oil on canvas, 91.4 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Veronika Pausova

Using texture and detail, Toronto artist Veronika Pausova creates paintings that look like microscopic studies, textile motifs and science fiction landscapes, with compositional references to Surrealism and Soviet Modernism. Pausova was one of two runners-up for the 2017 RBC Painting Competition and exhibited her most recent body of work at Hunt Kastner, in Prague, and with Simone Subal Gallery at Liste Art Fair in Basel. In these new paintings, hands and ears, amoeba like spiders and oranges run amok amid allusions to facial forms. Spiders and hands in particular are motifs that Pausova returns to frequently. She speaks of how her spiders respond to one another and “imitate a nearby space, sometimes pulling or stroking one another,” whereas the hands are action-based forms that “shift objects and change the space of the canvas—suggesting the presence of a ‘puppet master’ who directs the scene.” Viewed sequentially, these paintings create the sense of a dramatic unravelling—in some, a pair of hands pull apart hidden, layered narratives, revealing less-than-familiar-looking spiders and other forms, all about to escape their controlled environments. In many ways, these paintings have an eerie tone of forewarning and feel like a cautionary tale, a breaking point in the attempt to assert human dominance over the non-human world.

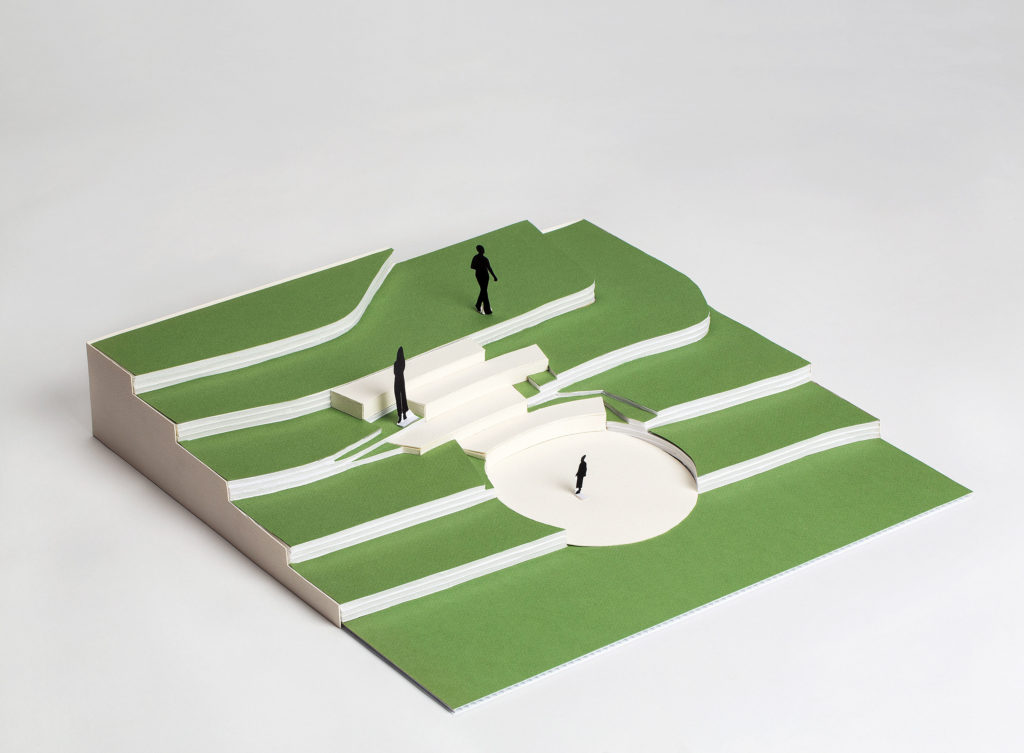

Tiffany Shaw-Collinge, pehonan (maquette), 2018. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Edmonton Arts Council.

Tiffany Shaw-Collinge, pehonan (maquette), 2018. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Edmonton Arts Council.

Tiffany Shaw-Collinge

Edmonton artist, curator and intern architect Tiffany Shaw-Collinge focuses on creating large-scale sculptural interventions. Her projects span both indoor and outdoor environments, demonstrating a strong material and spatial awareness. As part of the new Indigenous Art Park in Edmonton, Shaw-Collinge developed a site-specific public art work titled pehonan, Cree for “waiting place.” The location of the park, on the North Saskatchewan River, has been identified as an area used by Indigenous people for thousands of years. With this in mind, Shaw-Collinge, who is Métis, designed a four-tiered amphitheatre with a depressed grass circle at its base. Each tier is built with a different material—quartzite stone, wood, weathered steel and polished mirrored steel—relating to a specific historical period. As Shaw-Collinge explains, she researches “how materials degrade due to weathering and [tries] to utilize ones that shift over time, understanding that we are implicit with nature.” Entropy and the inevitable transformation of materials are ongoing sources of inspiration for Shaw-Collinge, who believes our relationship to climate has always been urgent.

Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill Idle Sun

Chair (from the Waste Lands

series) 2016 Scrap metal, gloves,

socks and gravel 76.2 x 53.7 x

61 cm COURTESY THE ARTIST

PHOTO RACHEL TOPHAM

Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill Idle Sun

Chair (from the Waste Lands

series) 2016 Scrap metal, gloves,

socks and gravel 76.2 x 53.7 x

61 cm COURTESY THE ARTIST

PHOTO RACHEL TOPHAM

Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill

The practice of Métis Vancouver artist Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill is driven by a desire to undermine capitalist economies of use. Between 2014 and 2017, the artist developed a project called Waste Lands, first shown at Vancouver project space Sunset Terrace and later as part of a group exhibition at the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. In this series of sculptures, Hill created compositions that appeal to modernist sensibilities by using materials from hidden or informal economies, such as metal recycling and can collecting. Seeing the potential in discarded objects such as old socks and gloves, pieces of insulation, a plastic chair, blankets and building materials, Hill explores alternative economic strategies that take inspiration from illicit activities. Elevating objects commonly understood as garbage, Hill points to the environmental danger of attitudes rooted in values of convenience and imagines a different life for rejected items, one in which they are desirable and hold new purpose. Waste Lands makes direct connection to the long-term effects that various approaches to consumerism have on the physical environment, including the division between what is private and public. Challenging an overarching economic climate that dictates how we use the land, Hill’s work questions how experience-based models, including Indigenous approaches to economics, might seed new ways of thinking about systems of exchange.

Kevin Michael Murphy, Sun Machine, 2016. Video floor-projection, 140 min 29 sec, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Kevin Michael Murphy, Sun Machine, 2016. Video floor-projection, 140 min 29 sec, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

Kevin Michael Murphy

The multidisciplinary practice of Toronto artist Kevin Michael Murphy questions the commodification of nature and responds to specific conditions of environmental crisis. His Petro-tourism (2017) is a series of serigraphs that trace the history of petrochemical and transportation sites in southern Ontario. Screenprinted using transparent ink and algae, the images allude to the fossilized organisms that become petroleum over time. The greenish tinge first seems atmospheric, as if these were monochromatic, toned photographs, but once the connection to oil is understood, associations with environmental toxicity become apparent. Unfixed surfaces allude to the cycles of change implicit in the production of oil and, like the natural resources consumed by humans, these images will fade and diminish over time. Challenging prevailing notions of oil as a dirty commodity, Murphy reminds viewers that oil itself isn’t the problem—our use of it is. For the video installation Sun Machine (2016), Murphy filmed the sun through the roof of his car during a road trip from his studio at the University of Guelph to Oil Springs, Ontario, site of the first commercial oil well in North America. Projected on the floor of the gallery, Murphy’s sun burns a figurative hole in the ground, mimicking the process of drilling an oil well. Collectively, these recent projects emphasize the disjuncture between manufactured perceptions of resource industries and the material existence of natural organisms, long before they become commodities.

Jessica Jang, Cloud Hands, 2018. Paper pulp, ceramics, acrylic paint, wood, charcoal, hand-dyed fabric, cushions and mural with Chinese ink, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Jessica Jang, Cloud Hands, 2018. Paper pulp, ceramics, acrylic paint, wood, charcoal, hand-dyed fabric, cushions and mural with Chinese ink, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Yuula Benivolski.

Jessica Jang

A recent graduate of the University of Guelph MFA program, artist Jessica Jang presented “Cloud Hands” at Xpace Cultural Centre in Toronto this past spring. Titled after a tai chi movement, the exhibition created an environment of intangible energies—with specific attention paid to the force of chi (integral to the balance of Yin-Yang) and the practice of feng shui. Cloud-like hands, mountains and rock forms were painted on the gallery walls in a series of gestural murals that enveloped a central seating area of pillows and stacked, rock-like sculptures, offering an unconventional place for the contemplation of energy. These rock structures refer to the scholar’s rock used in feng shui to replicate the idealized environment through which the force of chi moves. Locating sites for the optimal flow of chi was traditionally considered important in establishing the prosperity of civilizations. Accessing chi requires a profound reverence for the environment and its articulation through geography and weather, as well as a fundamental understanding that humans live harmoniously with nature rather than dominate it. This process of constant adaptation is a driving force for Jang. She questions concepts of “accommodation” in the divisions between Eastern and Western conventions, socially and environmentally, and finds herself negotiating these changing situations in her work.

Alex Tedlie-Stursberg, Warped Fountain (detail), 2018. Cement, sand, pennies, water, fountain pump, fibreglass, polystyrene and fake plant, 2.08 m x 68.6 cm x

71.1 cm. Courtesy Burrard Arts Foundation. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Alex Tedlie-Stursberg, Warped Fountain (detail), 2018. Cement, sand, pennies, water, fountain pump, fibreglass, polystyrene and fake plant, 2.08 m x 68.6 cm x

71.1 cm. Courtesy Burrard Arts Foundation. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Alex Tedlie-Stursberg

Curious about how one might dissociate familiar objects from their typical meanings, Vancouver artist Alex Tedlie-Stursberg often sources the materials for his work through thrift, salvage or barter to explore what he terms the “bottom end of the market.” For his project The Brazen Beach, developed while in residence at the Banff Centre, Tedlie-Stursberg created two sculptures using found organic and non-organic material sourced from the BC coastline and the Canadian monetary system. Specifically invested in understanding human impact on the ocean, Tedlie-Stursberg used Styrofoam detritus to create Untitled Bronze (Cosmic Egg), a pockmarked bronze sculpture that expels incense, and Globster, a concrete, water-recycling fountain embedded with pennies. Rather than offering a cynical critique on the state of the environment, Tedlie-Stursberg uses natural and discarded materials in tandem to explore human-driven change and our relationship to waste. This method of working, of taking rejected objects and reformulating them, continued in his exhibition “Everything Flows” at the Burrard Arts Foundation in Vancouver. Here, Tedlie-Stursberg expanded on concepts he developed in Banff, adding another sculptural fountain and building on ideas of accumulation and absurdity, continuing the playful provocation that these forms of manufactured detritus have a lifetime that likely exceeds our own. At first glance, many of his works are materially confusing and necessitate a careful unravelling of layers, to recognize the underlying structures, to notice the obsolete pennies or to observe that the water fountain absorbs its own water.

Tyler Los-Jones, As Lichens no. 8, 2017. Archival ink-jet print, 30.5 x 35.6 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Tyler Los-Jones, As Lichens no. 8, 2017. Archival ink-jet print, 30.5 x 35.6 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Tyler Los-Jones

Banff artist Tyler Los-Jones is deeply invested in challenging Western perceptions and representations of nature as pure and unspoiled. His site-based projects involve long periods of research that investigate environmental peculiarities. Following a 2015 residency at Gushul Studio in Blairmore, Alberta, an area known as the Crowsnest Pass, Los-Jones created a slow light, a body of work first shown at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery in 2017 and then at Division Gallery in Toronto. Crowsnest Pass, a notoriously narrow mountain valley formed from ancient seabeds, is a mineral-rich archaeological zone. While on residency, Los-Jones became aware of methods of wayfinding that changed in response to the shifting needs of local settler communities as they moved from resource extraction to tourism-based economies. Attempting to represent these complex navigational strategies, Los-Jones produced a series of photographic works, including one that plays on the prismatic shapes used to trace and observe a deceptive mountaintop by reflecting light; works that allude to the famous Burmis tree, now dead, which stands with only the aid of metal rods; and two hanging chains, composed of coal dust and epoxy, a reference to tools used to aid tourists who have lost their sense of verticality while visiting a defunct mine. Influenced by theorist Adam Bobbette, Los-Jones views photographic processes “as a form of fossilization”—an appropriate medium for exploring geologic time. These works emphasize the miniscule measure of human presence against the millions of years pressed into the rocks that shape the valley.

tunnel, A monument to tears (site documentation), 2017. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Jen Reimer.

tunnel, A monument to tears (site documentation), 2017. Courtesy the artists. Photo: Jen Reimer.

tunnel

Recorded in a subterranean cistern in Calgary, A monument to tears (2017) is an audio work by cross-country collaborators Jen Reimer (Montreal) and Magnus Tiesenhausen (Calgary), known collectively as tunnel. The Saddleridge reservoir, responsible for supplying water to the city of Calgary, functions on a 40-year cycle of operation before being drained for maintenance—during which time tunnel’s recording took place. Initiated by the sound of their voices, the artists created a 42-minute performance composed of a free-flowing sequence of echoes and reverberations throughout the cistern as they intuitively created sounds of response. The completed audio track is hypnotic, cavernous, resonant, as if it were monastic chanting from a different time. The cycle as a symbol of time is key to this work—the cycle of the cistern, the cycle of voices and the cycle of a lifetime. As the artists suggest, the “scale of experience of a human lifetime exacerbates environmental issues” because it is difficult to “imagine things…outside [of] linear time.” Conceptually, A monument to tears invokes the ebb and flow of the cistern as sound fills and dissipates through the space, much like how the cistern receives and releases water. Challenging the notion of fixed time through tonal fluidity, and experimenting with the fracturing of sound, it’s work that provokes a re-evaluation of human time in relation to a broader understanding of environmental and climatic time.

Mia Loeb, WEATHERED STEEL, CLAY (detail), 2017. Unfired clay and steel, 1.13 m x 90 cm x 40 cm. Courtesy Gerdarsafn Museum, Kópavogour. Photo: Claudia Hausfeld.

Mia Loeb, WEATHERED STEEL, CLAY (detail), 2017. Unfired clay and steel, 1.13 m x 90 cm x 40 cm. Courtesy Gerdarsafn Museum, Kópavogour. Photo: Claudia Hausfeld.

Mia Loeb

Born in Oslo and based in Vancouver, artist Mia Loeb works mainly in large-scale sculpture that contrasts industrial and organic materials. She recently completed her MFA at the Iceland Academy of the Arts in Reykjavík, and participated in a group exhibition at Iceland’s Gerðarsafn Museum in Kópavogur in 2017. Working with the language of minimalism, Loeb presented a series of floor works composed of steel sheets and clay. The steel used in the exhibition was “exposed to oxygen and water in the temperamental weather conditions of Iceland,” she explains, its warped and rusted forms resisting the appearance of industrialized perfection. Layers of wet clay, sourced locally and applied to the steel sheets, proceeded to dry and crack throughout the duration of the exhibition. For Loeb, this series was about tracing a temporal relationship between two materials as a way to respond to the strangeness of her physical location and the inclement climate of Iceland. Several of the shaped metal sheets, weighing a combined 900 pounds, appeared weightless; this trompe l’oeil effect positioned the materials as mutual support structures for one another. Loeb constructs a climate for these materials, outside the context of the local environment where they would normally meet, allowing them to react to each other, slowly.

Gillian Dykeman, Dispatches from the Feminist Utopian Future (teleporter II) (still), 2016. Single-channel video, 10 min 30 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Gillian Dykeman, Dispatches from the Feminist Utopian Future (teleporter II) (still), 2016. Single-channel video, 10 min 30 sec. Courtesy the artist.