Richelle Bear Hat

The suture between the wind-blown, yellow prairie grass and the fathomless blue of prairie skies has been a line of perennial fascination for artists. In Calgary-based Blackfoot and Cree artist Richelle Bear Hat’s latest video work, In Her Care (2017), it is rendered in such a tender and eponymously caring way that the landscape—whether marked by the ubiquitous Albertan infrastructure of transport trucks and trains, an Indigenous community centre, or just the grass and the sky—feels somehow distinct from all other attempts to represent it, visually or otherwise. Bear Hat recounts stories of her mother, aunties and grandmothers relating to the land and their insistence upon the use of Blackfoot to communicate with the artist since her childhood. “My great aunt Hilda would tease me in Blackfoot. She had fun in teaching me bad sayings. When I got it right, and she could understand what I was saying, she would laugh and laugh. I tried to learn as fast as possible, to hear her laugh,” Bear Hat narrates over the prairie vistas of her video. Close-up shots show hands, with perfectly manicured, light salmon-coloured nails, slowly, gently braiding sprigs of sage amid sweet grass and rose hips, as she speaks in Blackfoot, her mother tongue—a turn of phrase more apt here than anywhere. No translation is provided; what exists in those words is not for me to hear. They are for her grandmothers, her aunties and her mother: “she is part of the grass that grows here.”

Carly Butler, Anywhere Else 2014. Performance documentation.

Carly Butler, Anywhere Else 2014. Performance documentation.

Carly Butler

“Celestial navigation is considered by many as a pursuit that encompasses more than simply finding your way across an ocean; it is about the interconnectedness of the natural world; it challenges how we think about time and the universe,” says Ucluelet, BC, artist Carly Butler of her current research. It’s an endeavour entangled in, yet ardently critical of, the misty lore of sailor traditions—the creaking boards of old ships, stick-and-poke tattoos, the particularities of knot tying, rum and the workaday men of early colonialism— and the potential for wonder in a state of lostness. A finalist for the 2014 RBC Canadian Painting Competition, Butler takes the impulse to romanticize languages of navigation and myths of the sea, and, in her wide-ranging practice, turns instead to an earnest meditation on the auspicious aspects of symbols and modes of communication that have ceased to serve us in contemporary contexts. There is a striking parallel between her interest in Morse code—its own kind of language now incomprehensible to many—and the complex algorithms that engender our contemporary lives. What would happen if our GPS devices, smartphones, Apple Watches or cackling Amazon Alexas were to fail? Butler is interested in the value of near-obsolete forms of communication as viable means to navigate the world beyond a screen. Currently enrolled in a celestial navigation course, she is learning how to use a sextant—and by extension, the stars, the moon and the sun—to navigate, returning to near-lost knowledge as a way to be found in translation, found at sea.

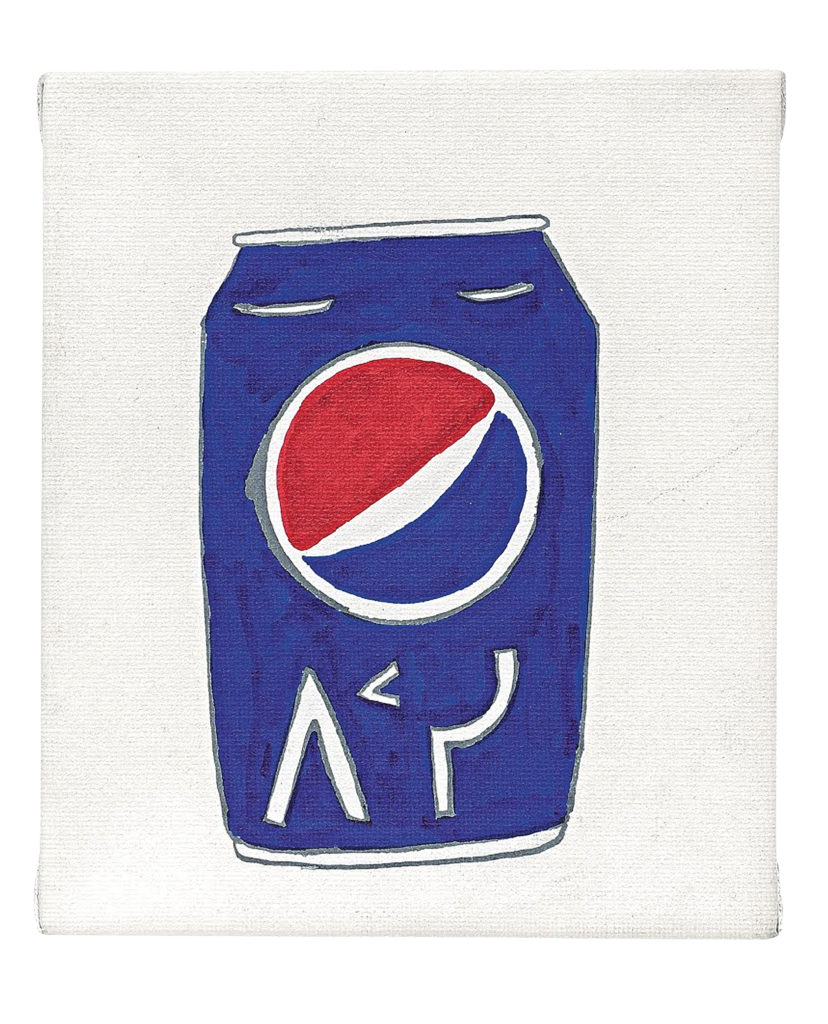

Adina Tarralik Duffy, Inuit Pop Art – Pipsi, 2015. Sharpie marker on canvas, 12 x 10 cm.

Adina Tarralik Duffy, Inuit Pop Art – Pipsi, 2015. Sharpie marker on canvas, 12 x 10 cm.

Adina Tarralik Duffy

ᑐᕌᖅᑕᕗᑦ, or Turaaqtavut, the Government of Nunavut’s official mandate, outlines actions, principles, teachings and priorities for Inuit self-governance, including imperatives for reclaiming language, culture and voice—a powerful and inextricable combination. Coral Harbour–based artist Adina Tarralik Duffy makes physical these foundational Inuit ideas with her use of Inuktitut syllabics in diverse contexts, a gesture that speaks to the profound importance of traditional ways of knowing. Such knowledge is not constituted by disparate, autonomous parts; language is culture is voice, and any permutation thereof. “[My work comes] from thinking about our ancestors and how much they were able to create from what seems like nothing,” she explains. “This idea of using everything you have and not wasting anything, whether it’s tools or an idea or a part of an animal that might otherwise be thrown away.” Duffy’s work does not sit easily within a single category of making. From writing to drawing, storytelling to sewing, and from being a new mother to repurposing beluga vertebrae, her multifaceted practice—including ᑲᓇᔪᖅ, or Ugly Fish, her small but productive design company—is a holistic being whose limbs work in concert to live and thrive. Writing about Inuk carver Henry Nakoolak, she says, “I offer him coffee or tea; he declines both but finally accepts my offer of a Pepsi.” In a 2015 work by Duffy, Inuit Pop Art – Pipsi, we see that same blue can, but with Inuktitut syllabics instead of English letters: ᐱᑉᓯ.

NIK, I am Sorry (Live), 2018. Performance documentation. Photo: Jeremy Pavka.

NIK, I am Sorry (Live), 2018. Performance documentation. Photo: Jeremy Pavka.

NIK

How can a body move in Serbian? This is a central question in Calgary artist NIK’s multidimensional performative practice. An ongoing suite of works under the moniker I’m sorry… occupies an indeterminate space between Eastern European cultural traditions and the prescribed norms of modern Western culture. Compelled by the prevalence of Western pop music in drag performances and queer cultures in Eastern Europe, NIK, as their drag persona Nikola, performs traditional ballads and simpering love songs, sung in Serbian and plucked on a Gusle—a one-stringed folk instrument that typically accompanies Dinaridic epic poetry—instead of the typical Cher, Madonna, Lana Del Ray and Whitney Houston anthems that have come to proliferate in drag across cultures. Highly self-aware, these performances are tender queries of how to be in the interstitial space of culture, geography and gender. In a new video work, I am sorry #26 – Not Angel, But Angel, the artist is in nondescript, dingy hallway spaces, dancing with a durational fervour, an ecstasy. As Nikola juts and jogs and throws their arms, subtitles in English translate their movements imperfectly into an urgent yet poetic treatise born of an exercise in automatic writing. The process of translating from movement to language, between two fixed points of gender and across two cultures, is for NIK a galvanizing practice to summon love for bodies, including theirs, that don’t neatly fit the often limiting and violent categories built for us to ostensibly live within.

The cabbage (or kapusta in Ukrainian) is a central metaphor for history and reality in Erín Moure’s play Kapusta.

The cabbage (or kapusta in Ukrainian) is a central metaphor for history and reality in Erín Moure’s play Kapusta.

Erín Moure

A surreal cast of characters, including a “woman in 40s or 50s, simply a vowel” known as “E.,” a “marionette 1-meter high, woman in her 40s with the easeful glamour of a young Jackie Kennedy pre-1963, before a shot” and маленька дочка, “Malenka Dotchka, little daughter, a sock monkey in an apron, a vest, various hats,” populate Erín Moure’s Kapusta, a rare thing that exists as pages but exceeds the category of book, by several dimensions. Published in 2015 and written in French and English, with occasional interventions in Ukrainian, Kapusta is an alchemical cookbook of language, history, heartbreak and wonder. It is a play in the absurdist tradition, its acts and scenes unfolding “like peeling leaf after leaf off a cabbage,” says Moure. The story takes place largely in Alberta, where E. finds refuge on a bench behind her grandmother’s woodstove, much like Moure’s grandparents who took refuge in the prairie province before the Great Depression and the genocidal chaos of the Second World War. We are disclaimed at the very start: “Note: At times, actors read not just their lines, but the stage directions, and even the lines of others. They use as much French as the local audience can bear, but should at least use a few phrases. ‘The language of the text is obsessional, and this must be faced.’” Moure’s stage is proscenium-less, just as her page is marginless. Here, translation is not tethered to different languages, but is rather an exercise to make the reader move their head from side to side, from French to English, to gesture “no” to the violence of history, which always desires to remain senseless.

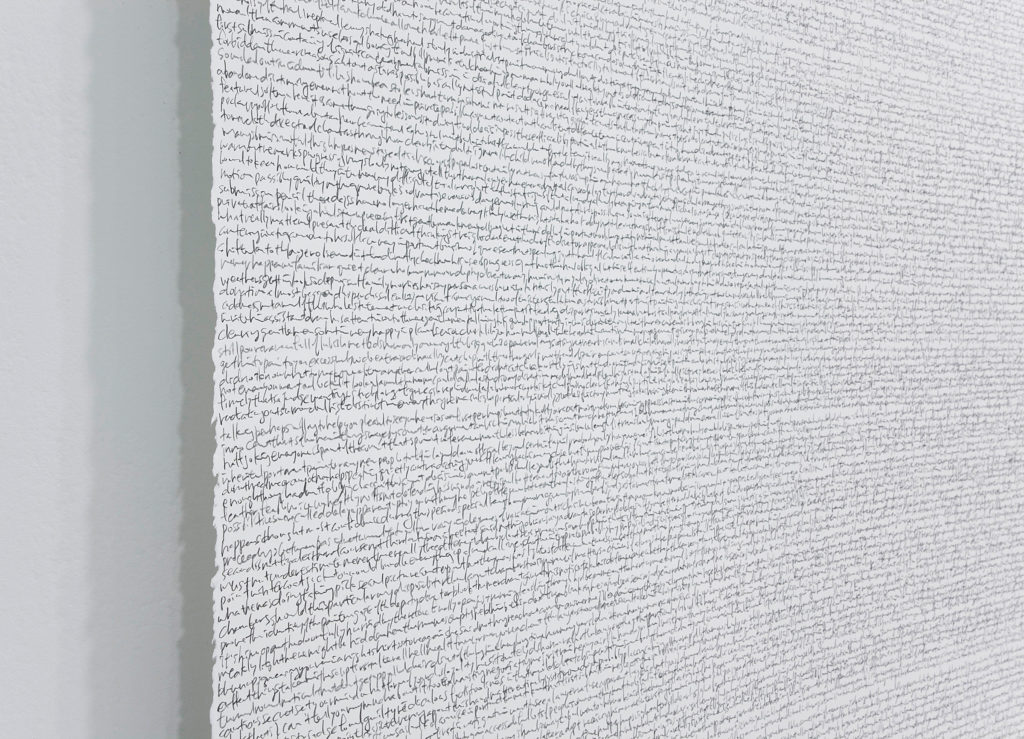

Hyang Cho, Trial 2 (detail), 2012. Graphite pencil on Stonehenge paper roll, 11.8 x 1.28 m. Courtesy

Georgia Scherman Projects. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Hyang Cho, Trial 2 (detail), 2012. Graphite pencil on Stonehenge paper roll, 11.8 x 1.28 m. Courtesy

Georgia Scherman Projects. Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay.

Hyang Cho

All texts have lives. Even if not explicitly translated from one language to another, texts endure and are read, re-read and interpreted anew from subjectivities and vantage points across time and contexts. What is lost in translation—the gaps, the rifts, the misunderstandings— can become generative, lush landscapes rather than potholed vistas. For Guelph artist Hyang Cho, ideas of translation are wholly entangled in these relationships of text and meaning; her experience of one language is fully bound up in her knowledge of another. Cho’s recent and past works—born of the machinations of learning English, and the labour of shuttling from one language to the next—deal in Sisyphean feats related to these processes. In a series of works that instrumentalize Kafka’s The Trial, the artist typed out the entirety of an audio book version of the text eight times, hand-wrote a transcription of the full text on a wildly long roll of Stonehenge paper, and reproduced the original German manuscript’s ninth chapter in pencil. Each version is marked by its own idiosyncratic holes and mistakes. These endeavours, like much of Cho’s work, advocate for a textural rather than textual encounter, a form of writing that, when abstracted, asks not for linguistic understanding, but for the possibilities of an aesthetic experience of words on a page.

Anna Semenoff, What’s yours is mine, 2017. Carpet, Plexiglas and glass. Installation view in “Echolalias,” curated by Areum Kim at Stride Gallery. Photo: Nicole Kelly Westman.

Anna Semenoff, What’s yours is mine, 2017. Carpet, Plexiglas and glass. Installation view in “Echolalias,” curated by Areum Kim at Stride Gallery. Photo: Nicole Kelly Westman.

Areum Kim

In 1996, the Government of South Korea founded the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI), whose machinations are aimed toward the diffusion of Korean literature, to be subsequently consumed globally in varied languages: a cultural export machine par excellence. Calgary curator Areum Kim cites this governmental body, and its prescriptive approach to translation that encourages glossing over Korean cultural nuance for the sake of legibility in other languages, such as English, as an instigating inspiration for her research into issues of translation in artistic practice. LTI prioritizes “a ‘smooth translation’ of Korean particularities, whether they be pop culture references, historical contexts, or ‘untranslatable’ words or phrases,” says Kim. “Many texts that are translated into Korean deploy a liberal use of footnotes, and the fragmentation of the reading experience is in favour of the learning and understanding of the original text’s contexts. Thus the onus of familiarizing oneself is on the reader—why is this not also expected of the Western reader? I found that a disturbing agenda, something very familiar to the burdens of the colonial subject.” Kim’s recent curatorial projects, “Tongues, Echoes” at Access Gallery in Vancouver and “Echolalias” at Stride Gallery in Calgary, take on the shortfalls of the impulse to regiment and police translation, proposing instead that translation is a process of decolonization; an anatomical exercise; a sensual endeavour; a documentation of the transmission of ancestral knowledge; a reclaiming of authority; and broadly, a practice of resistance.

Miruna Dragan, In the sage telestic waters... I see... (detail), 2017. Water-cast aluminum mobile, dimensions variable. Photo: Nicole Kelly Westman.

Miruna Dragan, In the sage telestic waters... I see... (detail), 2017. Water-cast aluminum mobile, dimensions variable. Photo: Nicole Kelly Westman.

Miruna Dragan

The practice of molybdomancy—a sort of residue of alchemical inquiry that originated in Ancient Greece—has persisted through millennia in the careful and resolute hands of wise women, and now exists in varied forms in Nordic and Central Europe, and Turkey. Traditionally invoked on New Year’s Eve, molybdomancy is a means of divining by pouring molten metal into cool water, resulting in the quick solidifying of the alloy into forms that are then interpreted, either directly or via the shadows they cast. Calgary artist Miruna Dragan’s In the sage telestic waters… I see… (2016–) is a large-scale exercise of such divination; the artist dropped substantial quantities of liquid aluminum into vats of cold water to create stalactite- and stalagmite-like structures. These forms are malleable in that they can be arranged in innumerable permutations; light and shadow are translated into meaning and fortune, molten metal into objects of preternatural significance. A recent iteration of this work included a performance with sound artist Kylie Ward that translated the narration of dreams into tonal frequencies. “Our method was to use colour corresponding to the frequencies of the notes,” explains Dragan. “The writing on top records the notes and words that were spoken on a loose timeline, the idea being that it becomes a score after the fact, another translation. The colour of sound, the projected colour of the aluminum mobile in the gallery, together, are part of the same continuum: the spectrum of light.”

Sahar Te, KHAAREJ No.2, 2017. Performance, 13 min. Performers: Louisa Brianna Adria and Craig Fahner. Site: Shannon Bool's exhibition "The Eastern Carpet in the Western World Revisited" at Illingworth Kerr Gallery, ACAD. Photo: Chelsea Yang-Smith.

Sahar Te, KHAAREJ No.2, 2017. Performance, 13 min. Performers: Louisa Brianna Adria and Craig Fahner. Site: Shannon Bool's exhibition "The Eastern Carpet in the Western World Revisited" at Illingworth Kerr Gallery, ACAD. Photo: Chelsea Yang-Smith.

Sahar Te

“I had used translation enough as a subject matter itself, so I became interested in using translation as a methodology, moving from talking about translation to talking through translation,” says Toronto artist Sahar Te. Her KHAAREJ No.2 (2017) is an operatic performance wherein an English-speaking singer accompanied by a drummer improvises Farsi words from a free-form poem, written by Te, to evoke the lyrical nature of a language’s incomprehensibility to those who don’t speak it. TARJOME/ همجرت /_UU/TRANSLATION (2017) is a text-based installation that uses approaches to translation inspired by the work of Jacques Derrida, Jorge Luis Borges and Vladimir Nabokov to yield varied English versions of a Farsi poem that exemplify generative possibilities within the ultimately irresolute nature of translation. Te’s recent work The Price, in 100 Notes (2017) centres on the inversely related trends in oil prices in Alberta and Iran. Here translation is a methodology to investigate the complex ways in which all manner of things—data, economics, familial experience—circulate and interact in our world. Transforming fluctuating oil prices across 100 months, from January 2009 to May 2017, into musical scores, which are then performed by musicians playing the viola and santur against backdrops of morphing colours, The Price, in 100 Notes speaks to the commensurability of sound and light, and oil and gas, in their effects on our bodies, our relations and our ways of being in a late-capitalist context.

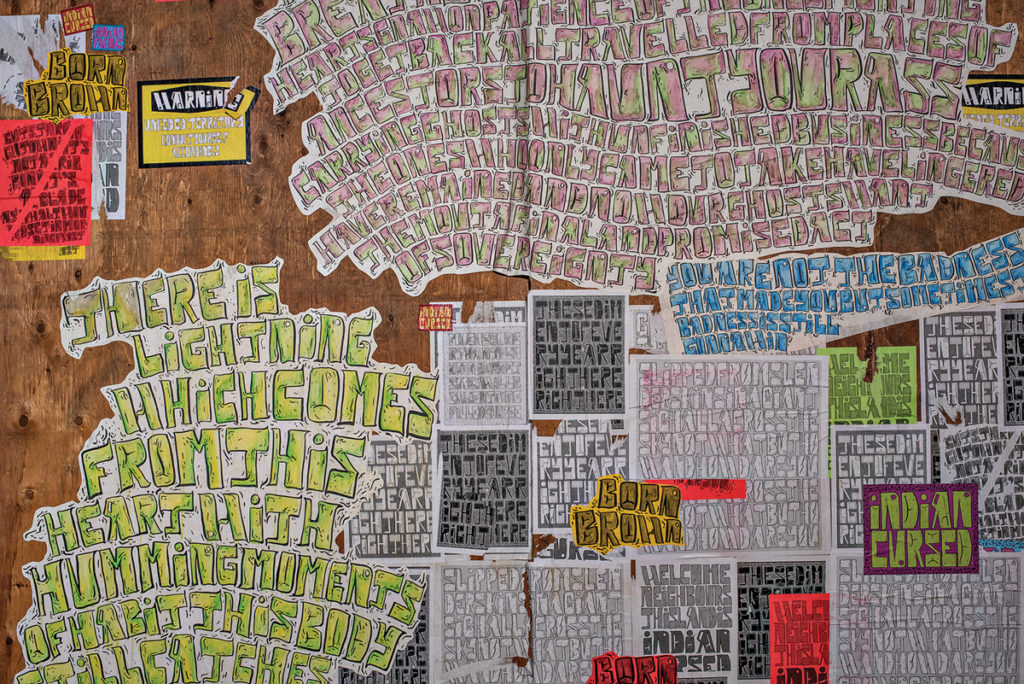

Whess Harman, echoes go louder (detail), 2017. Wheatpaste, ink and watercolour, dimensions variable. Photo: David Barbour.

Whess Harman, echoes go louder (detail), 2017. Wheatpaste, ink and watercolour, dimensions variable. Photo: David Barbour.

Whess Harman

“My work comes from a desire to shout and call forward while embracing the scrambled paroxysms of descriptors and scraps we use to be understood by others,” Whess Harman says of the complex and churning forces that compel their practice. “The use of juxtapositions and the elevation of vague but seemingly poetic or humorous statements are strategies I use as a way to deliberately highlight mistranslations and misunderstandings in identities that are constantly renovated and commissioned upon by ourselves and others.” Harman, a member of the Carrier Witat, Lake Babine Nation, and born in Prince Rupert, BC, on the unceded territory of the Tsimshian people, uses strategies of obfuscation in their work through the use of traditional West Coast Indigenous motifs. Harman denies easy consumption of their chosen phrases, which lie somewhere between a protest cry and a truism, a spray-painted tag and a profound observation, always with an anti-colonial core. Their methodology is a critically queer one; obscuring is protective, a means to deny information to the colonial, patriarchal gazes to which bodies and beings are subject on a daily basis. A form of translation is required here, not from one language to another but rather from colonial, binary ways of being into something more nuanced and complex—a powerful unfixity.

RBC is passionately committed to supporting emerging artists across Canada and internationally, and is proud to partner with Canadian Art on this Spotlight series.

Richelle Bear Hat, In Her Care (still), 2017. Single-channel video, 10 min. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery.

Richelle Bear Hat, In Her Care (still), 2017. Single-channel video, 10 min. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery.