In January 2019, Black Wimmin Artists (BWA), a collective created by Anique Jordan on WhatsApp in 2016, organized The Feast: a dinner performance for 100 Black women and gender non-conforming artists that also honoured the 30th anniversary of the 1989 exhibition “Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter.” The Feast occupied the literal epicentre of the institution, convening in the Art Gallery of Ontario’s Walker Court. The grand gesture was not only a commemoration; it also asked the question, as Jordan phrased it: “Why haven’t we been exposed to more of the work, ideas and perspectives of Black wimmin artists in Canada?”

As the second decade of the 21st century rolls out, it’s worth reflecting on the legacy of this groundbreaking 1989 exhibition. Organized by the Diasporic African Women’s Art (DAWA) collective, it was the first of its kind in Canada to be curated and feature artwork exclusively by Black women. In this process of self-authorization, DAWA members named themselves agents of their own cultural production, and their exhibition created sites of resistance in which they confronted cultural stereotypes about Black women, Black women artists and their artistic practices.

DAWA was formed as a nonprofit community network in 1984, at a time when national identity politics were marked by ongoing debates about fledgling multiculturalism, and significant anti-racist, feminist and queer activism. At that historical moment, “Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter” marked the entry of Black women artists into the Canadian art scene. DAWA organized work by 11 artists from Toronto, Ottawa, Kingston, Montreal and Edmonton into a show that confronted the dominant Eurocentric perspectives set on denigrating ethnocultural art as second-rate Outsider art. In doing so, it took up the challenge of making the Canadian art scene feel like home. Opening at Toronto’s A Space Gallery on January 28, 1989, the exhibition then travelled to Houseworks Gallery and Café in Ottawa, Xchanges Gallery in Victoria, Articule in Montreal and Eyelevel Gallery in Halifax, where it closed on September 23.

As an art historian—one whose first published journal article, in 1996, was a version of my MA thesis on “Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter”—I have been deeply enthralled by the prominence that Black arts and culture have reached in Canadian contemporary cultural history since my own journey began. And yet if I were to search “Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter” online today, the results would overwhelmingly list either references to my own MA thesis or, if not, jump to entries about The Feast in 2019. The historical displacement of diasporic Black folks, from the institution of slavery to current exploitative labour structures and everyday racism, has profoundly affected their ability to situate a “homeplace,” a safe place where, to draw from bell hooks, “black people could affirm one another and by so doing heal many of the wounds inflicted by racist domination.” Not surprisingly, the issue of home and memory were crucial sites of resistance explored in a number of the works in “Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter,” whose multisensory media ranged from textiles, wooden boxes and tree branches to dolls (Chloë Onari), Haitian vévés (Barbara Prézeau-Stephenson), music and incense.

In their curatorial notes, DAWA members Buseje Bailey and Grace Channer described the exhibition layout as “organized into several discrete areas, reflecting the communal compounds of traditional African society. Within these spaces, sculpture, constructions, music, poetry, fabric, painting and movement…comprise[d] a creative document of diasporic, African imagery.” Dzian Lacharité’s Right Time, Right Place (1989), for example, was a spacious bamboo dwelling visitors could enter barefoot; they were invited to walk on sand and experience the sensations evoked by ideas of refuge, shelter and home. Related works focused on the mnemonics of Black women and the politics of cultural amnesia, as in the counter-memories embodied in Winsom’s textile installation Kumbukumbu (1989) (Swahili for “memories”), a papier-mâché map of the African continent strewn with chains, and Suli Williams’s Happy Birthday Daisy, through her hands (1989), a series of mother-daughter paintings displayed inside a muslin tent constructed as a homage to her grandmother.

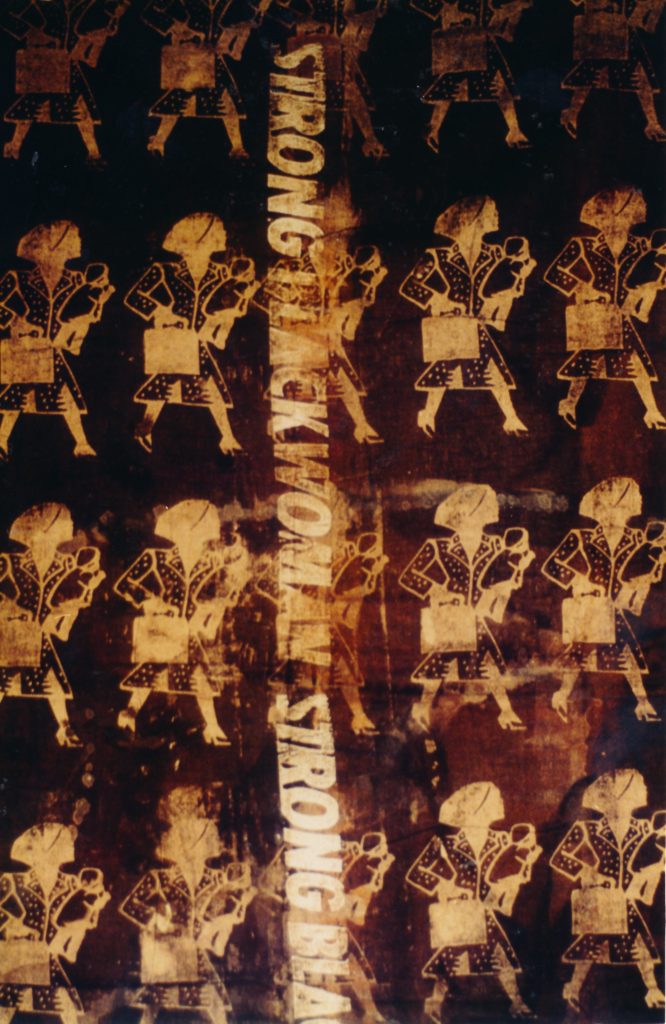

By contrast, the works of Grace Channer, Khadejha McCall and Buseje Bailey dealt with prevailing stereotypes of Black women in society, from ritualized fertility goddesses to the mammy. Channer’s Ba Thari (1989) (a Sesotho phrase meaning “women from whom generations come”) was a mixed-media floor sculpture made of twigs, branches, shredded cloth and a piece of driftwood. For Channer, “the resilience of Black women was echoed by that of the driftwood which had passed through many eras . . . and touched many shores [but] still survived to tell its stories.” McCall used elaborately screenprinted and batik textiles to depict different perceptions of Black women, such as in Strong Black Woman (1989), which portrayed a Black “super mom” and a female “buppie” (Black urban professional) challenging the male-dominated business world. Lastly, Bailey’s mixed-media work on panel The Black Box (1989) addressed the image of Black motherhood in a tribute to the artist’s Black female family members and Black women’s history from slavery to the present day.

That the entry of Black artists in the annals of Canadian art has been sadly protracted is irrefutable, but equally so is the importance of the here and now. Emerging and established Black Canadian artists alike are exploring Black-Indigenous relations and connections with other racialized communities in the settler colonial context of the Americas. Historical gaps remain before, during and after the legacy exhibition “Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter,” and there is obviously ample work for a new generation of historians in the field of Black Canadian art to fill them. Bring it on!

Khadejha McCall, Strong Black Woman, 1989. Copy art, silkscreen print, handprint and paint on unstretched canvas, 1.22 m x 91 cm.

Khadejha McCall, Strong Black Woman, 1989. Copy art, silkscreen print, handprint and paint on unstretched canvas, 1.22 m x 91 cm.